Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.2, 213-222 Published Online April 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.22028 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 213 Wives’ Employment and Marital Dissolution: Consideration of Gender Ideology and Marital Interaction Deniz Yucel Department of Sociology, William Paterson University of New Jersey, Wayne, USA Email: yuceld@wpunj.edu Received December 8th, 2011; revised January 17th, 2012; accepted February 22nd, 2012 This study examines both the mediating effects of marital interaction and gender ideology, as well as the moderating effect of gender ideology in understanding the relationship between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution. This paper also explores the role of gender for couples who disagree in their relation- ship assessments. Wives’ additional work hours are positively associated with marital dissolution, an ef- fect that operates through increased gender egalitarianism (for both spouses and for wives only) and de- creased marital interaction (for both spouses and for wives only). Lastly, for couples who differ in their reports of gender ideology and marital interaction, the likelihood of marital dissolution is contingent upon wives’ assessments of their relationship. The implications of this study and the avenues for future re- search are also discussed. Keywords: Wives’ Employment; Marital Dissolution; Gender Ideology; Marital Interaction Introduction Wives’ employment has long been studied and considered as one determinant of marital instability (Booth, Johnson, White, & Edwards, 1984; Greenstein, 1990, 1995; Johnson, 2004; South & Spitze, 1986; Spitze & South, 1985). However, schol- ars do not yet agree about the underlying mechanisms that link wives’ work hours to marital dissolution. Using three theoreti- cal frameworks–the attachment hypothesis (Hill, 1988), role strain theory (Goode, 1960), and the ideological consistency argument (Ross & Sawhill, 1975)—this study tests how and when wives’ work hours are associated with marital dissolution (i.e., the mediating and moderating mechanisms). Specifically, this study explores: 1) whether there is a direct relationship between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution; 2) whether couples’ marital interaction mediates the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution (testing the attachment hypothesis); 3) whether couples’ gender ideology mediates the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution (testing role strain theory); 4) whether couples’ gender ideology moderates the relationship between wives’ increased work hours and marital dissolution (testing the ideological consistency hypothesis); and 5) whether, among couples with conflicting reports, marital dissolution depends on the spouses’ respective assessments of the relationship. Here, marital interaction is defined as the amount of any time spent between spouses, while gender ide- ologies denote “how a person identifies herself or himself with regard to marital and family roles that are traditionally linked to gender” (Greenstein, 1996b: p. 586). I tested these five ques- tions using nationally representative data from the first two waves of the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH). NSFH is a nationally representative dataset that is designed to provide a broad range of information on family life, to serve as a resource for research across disciplinary perspec- tives. Each “wave” of data represents a time when interviews (in this case, with couples) are conducted. In this study, I used the first two waves: interviews in 1987-1988 (first wave) and in 1992-1994 (second wave). Literature Review and Hypotheses Wives’ Work Hours and Marital Dissolution Most prior studies have confirmed that wives’ work hours are positively associated with marital dissolution (Booth et al., 1984; Johnson, 2004; South & Spitze, 1986; Spitze & South, 1985). Some other research, however, has tested the reverse relationship: the effect of anticipated divorce risk on labor sup- ply (Greene & Quester, 1982; Montalto & Gerner, 1998; Sen, 2000). Sen (2000) constructs a longitudinal dataset and com- pares two cohorts: the National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women NLSYW for 1968-1983 and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1979 for 1979-1993. Her measure of divorce risk was a dummy variable indicating whether divorce or separation occurred in the next three years. Her results sug- gest that the risk of divorce significantly increased the labor supply, but by less in the more recent cohort. Despite these inconsistent findings, only a few studies have tested the mediating and moderating mechanisms of this asso- ciation (Greenstein, 1995; Poortman, 2005; Spitze & South, 1985). This study makes a contribution to research by including couple-level measures of marital interaction and gender ideol- ogy, and by testing the mediating effects of couples’ gender ideology and marital interaction, and the moderating effect of couples’ gender ideology, to explain the relationship between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution. I expect to find a significant and positive relationship between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution, even after controlling for couples’ cha- racteristics (Hypothesis 1 ). The Mediating Effect of Marital Interaction—Testing the Attachment Hypothesis According to the attachment hypothesis, marital interaction is  D. YUCEL one of the key factors that affect marital stability. Couples who interact fewer hours per week are more likely to have a failed marriage (Spitze & South, 1985). Prior research also has shown that employed mothers have a more strained experience of bal- ancing work-family roles, and that marital interaction and qual- ity are compromised when dual-earner couples have children (Hill, 1988; Kingston & Nock, 1987; Voydanoff, 1988). Con- sistent with the attachment hypothesis, Hill (1988) argued that pleasurable, shared time is marriage-specific capital that dis- courages divorce. Her study of the use of leisure time, in rela- tion to marital dissolution five years later, supports this argu- ment. Indeed, in multivariate models that include both spouses’ earnings and gender role conflicts, a lack of leisure time is sec- ond only to short marital duration in increasing the risk of divorce. On the other hand, a limited number of studies have found that marital interaction has no mediating effect between wives’ work hours and an increased divorce risk (Poortman, 2005). Poortman, however, suggested an explanation for this insig- nificant effect. First, her study was based on a sample from the Netherlands, which is characterized by a strong welfare system and a strong focus on family life. According to Poortman, we might expect the mediating effect (if any) to be smaller in such a sample. Second, her study was limited to couples in their early marriage; she argues that marital interaction is usually more important during early marriage. Nevertheless, some re- search has suggested that the effect of marital interaction on marital quality is stronger in long-term marriages (Schmitt, Matthias, & Shapiro, 2007), and that the mediating effect of marital interaction on the association between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution is likewise stronger in long-term marriages (Yucel, 2012). Despite these inconsistent findings, I expect to find that couples’ marital interaction mediates the effect of wives’ employment hours on marital dissolution (Hy- pothesis 2). The Mediating and Moderating Effect of Gender Ideology—Testing Role Strain Theory a nd Ideological Consistency Hypothesis Goode’s role strain theory (1960) suggests that people cannot perform as effectively when they are given different roles to play. Women’s paid employment may influence their ideologi- cal support for gender equality by increasing their exposure to social networks that support gender equality, and by providing them with a greater stake in improving women’s economic position (Bolzendahl & Myers, 2004). In addition, many studies have found that paid employment increases women’s support for an equal division of domestic roles between men and women (Coverdill, Kraft, & Manley, 1996; Davis & Greenstein, 2009; Fan & Marini, 2000; Huber & Spitze, 1981; Minnotte, Minnotte, Pederson, Mannon, & Kiger, 2010). This gender ega- litarianism might lead to strain between wives’ work and family roles, leading to more dissatisfaction with the gendered division of labor—which may in turn lower marital quality and increase marital dissolution. Consistent with these approaches, research has found that gender ideology mediates the effect of wives’ employment on marital dissolution (Greenstein, 1995; Sayer & Bianchi, 2000). Overall, I expect to find that the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution operates through wives being more supportive of gender equality than their hus- bands are (Hypothesis 3 ). The effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution may also be contingent on couples’ gender ideology. Gender ideol- ogy defines expectations about the “appropriate” male and fe- male marital roles (Greenstein, 1995, 1996a). The ideological consistency argument (Ross & Sawhill, 1975) suggests that in- consistency between these gender ideologies and marital roles decreases marital stability. Previous studies have explored the moderating effect of gender ideology on marital dissolution (Greenstein, 1995; Spitze & South, 1985). These studies found that the effect of wives’ work hours on divorce is stronger and indeed only significant for couples in which the husband disap- proved of his wife working (Spitze & South, 1985). Research found that wives’ work hours have no significant effect on marital dissolution when wives support traditional gender ide- ology, a nearly statistically significant effect for women with mod- erate gender ideology, and a strong positive effect on marital insta- bility for non-traditional women (Greenstein, 1995). Other studies have found that gender ideology has a moder- ating effect on marital quality (Greenstein, 1996a; Nordenmark & Nyman, 2003). Greenstein (1996a) found that inequalities in the division of household labor were strongly related to percep- tions of inequality, which were then related to the perceived quality of the marital relationship. The results in this study suggest that these associations are significantly stronger for egalitarian wives than they are for traditional wives. Therefore, I expect to find that the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution is strongest when wives hold more egalitarian views than their husbands. In other words, I predict that when the wives have a more egalitarian gender ideology than their hus- bands, an increase in wives’ work hours will be a destabilizing force in their marriage, leading to a higher likelihood of marital dissolution. Conversely, I predict that when wives have a more traditional gender ideology than their husbands, an increase in wives’ work hours will have less or no effect on the likelihood of divorce (Hypothesis 4). The Role of Gender The family has always been a gendered institution, and re- search suggests that the characteristic roles of husbands and wives have different influences on marital disruption. Specifi- cally, Heaton and Blake (1999) found a positive relationship between marital disagreement and marital dissolution for both spouses, as well as a negative relationship between marital happiness and marital dissolution for both spouses; the wives’ coefficients were significantly higher than the husbands’. They concluded that wives’ evaluations of marital quality are better predictors of marital dissolution than their husbands’. However, Sanchez and Gager (2000) and Gager and Sanchez (2003) found the opposite result: husbands’ negative perceptions of disagree- ments and unhappiness were better predictors of marital disso- lution than were negative reports by the wives. They argued that wives’ views might be discounted in their relationships and that wives might experience less marital power, higher barriers to leaving a marriage, and fewer alternatives to their current situation. Hochschild (1989) argues that gender inequality in society has an impact on wives’ expectations of their marriages such that, despite their desire for equality and personal satisfac- tion in their marriages, they cannot fight for equality and feel pressured to disregard negative feelings. Past research also concludes that the financial consequences of divorce might be more severe for wives than for husbands (Duncan & Hoffman, 1985; Holden & Smock, 1991). Therefore, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 214  D. YUCEL wives might be discouraged by the consequences of divorce and less inclined to end their marriages, even if they are un- happy (Sanchez & Gager, 2000). On the other hand, even though social and economic changes have reduced husbands’ power in marriage, male privilege is still expected to protect men against the detrimental effects of a bad marriage. There- fore, men might prefer an unsatisfactory marriage to no mar- riage at all, and, thus wives’ assessments of their relationship might be more important in determining marital success (Nock, 1998). I used couple-level measures for each variable from both husbands and wives. Measuring the relative characteristics of husbands and wives has several benefits. First, we can test the effect of spouses having consistent or conflicting views on marital dissolution. Second, it highlights the role of gender in married couples’ assessments of their relationships (Brown, 2000). Despite these different approaches and findings, I expect to find that consistency between spouses’ reports is correlated with lower marital dissolution; however, conflicting reports are correlated with higher marital dissolution. I also expect to find that, when there is inconsistency between spouses’ reports in gender ideology and marital interaction, wives’ assessments of the relationship determine marital dissolution (Hypothesis 5). Data and Methods This study used data from the first two waves of the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH). The NSFH is a national sample that includes 13,007 primary respondents, aged 19 and older, who were first interviewed in 1987-1988. The sample includes a main cross-section of 9643 households, and oversamples Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, sin- gle-parent families, families with step-children, cohabiting couples, and recently married persons. In Wave 1, one adult per household was randomly selected as the primary respondent. In addition, a shorter self-administered questionnaire was given to the respondent’s spouse or cohabiting partner. Wave 2 (1992- 1994) included interviews with the original respondents from Wave 1, the current spouse or cohabiting partner, and, in cases where the relationship from Wave 1 had ended, with spouses or partners from the previous relationships. This study’s sample included the married primary respondents from Wave 1 (N = 6877) whose spouses completed the questionnaire (N = 5637); this constitutes 82 percent of the married couples surveyed. From the 5637 married couples who fit these criteria, this study’s sample was limited to the respondents who had an iden- tifiable marital status at Wave 2 because at least one member of the original couple was interviewed (N = 4581). This group made up 81 percent of the married couples who completed the questionnaire. In addition, there were too few individuals be- longing to American Indian or Asian racial groups; thus, they were removed from the sample (both husbands (N = 61) and wives (N = 29)), leaving a sample of 4491 couples. Overall, the sample contains Whites, African Americans, and Hispanic re- spondents. The use of this dataset has several advantages. First, unlike many other studies, this study collected data from both wives and husbands. It is important to include both spouses’ reports because their reports might vary, and each may affect marital outcomes differently. Second, the NSFH includes indicators of many aspects of family life, including detailed individual char- acteristics, marital experiences, employment histories, and in- formation about employment and income (Sweet, Bumpass, & Call, 1988). Therefore, the NSFH is an excellent source of data for analyzing the determinants of marital disruption. Despite the many advantages of using NSFH data, there are some limi- tations. One limitation is that I did not use the third wave of NSFH data (2001-2003). By using the third wave, studies might investigate data on married couples at Wave 1 and changes in employment, marital interaction, and gender ideology between the first two waves, and analyze the effects of these changes on marital outcomes in Wave 3. Thus, these analyses could test the causal relationship between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution. In addition, this would permit researchers to exam- ine whether the adverse effects of wives’ work hours may have decreased in recent years, and also test whether it is among those unstable marriages that the wives work longer hours to be economically independent. This study uses only the first two waves of the NSFH data because data for the third wave from 2001-2003 (NSFH3; Sweet & Bumpass, 2002) were collected through telephone interviews with only primary respondents who were either above age 45 or had a child who was interviewed in wave 2, as well as with their spouses and their previously interviewed children. Therefore, the sample size of the third wave survey is considerably lower than in the first two waves. Given the attri- tion from the third wave, the serious limitations of this data set may increase in future waves of data. A second limitation is that the initial wave of the NSFH data is now more than fifteen years old, which raises the question of whether patterns docu- mented using these data are valid for today’s marriages. From Amato, Johnson, Booth, And Rogers’ (2003) comparison of marrieds from samples drawn in 1980 and 2000, it appears that divorce proneness has not changed much. The proportion of women who worked outside their homes increased rapidly from the 1960s to the 1990s, but in the 1990s, women's labor-force participation rate leveled off, and even slightly decreased in the early 2000s (Percheski, 2008; Vere, 2007). Thus, as the purpose of our analysis is to examine the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution, I can be more confident that the findings of this study are applicable to today’s marriages. Handling Missing Data Contrary to conventional methods, this study imputed miss- ing values using the ICE (imputation by chained equations) multiple-imputation scheme in STATA. This procedure gener- ates five data sets in which missing information is imputed by regressing each variable with missing data on all observed variables, and adding random error to the imputed values to maintain variability. This approach allowed me to use the study’s entire sample (N = 4491 married couples). Measurement of Variables Table 1 summarizes the measurement of the variables used in this analysis. With the exception of the dependent variable, marital dissolution, all of the variables were measured at Wave 1. The dependent variable measures the marital status of the cou- ples at Wave 2, thereby distinguishing between couples who sepa- rated or divorced from those who remained married at Wave 2. Independent Variab le s Wives’ Work Hours The primary independent variable was wives’ work hours. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 215  D. YUCEL Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 216 Table 1. Measurement of variables. Variables Measurement Dependent variable Marital dissolution Dummy variable was coded 1 if permanent separation or divorce took place between Waves 1 and 2 and 0 if they stayed married. Independent variables Wives’ work hours Hours worked in the previous week if that is the usual number of hours worked; usual hours worked per week if otherwise. Marital interaction One item asking, “During the past month, about how often did you and your spouse spend time alone with each other, talking, or sharing an activity?” (1 = never to 6 = almost every day). Dummy variables: both spouses have high marital interaction; both spouses have low marital interaction; wives have high and husbands have low marital interaction; husbands have high and wives have low marital interaction. Both spouses reporting high marital interaction is the reference category. Gender ideology Four items indicating how much they agree with the first four statements (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree) and two items indicating how much they approve of the final two circumstances (1 = strongly approve to 7 = strongly disapprove). 1) “It is much better for everyone if the man earns the main living, and the woman takes care of the home and family.” 2) “Preschool children are likely to suffer if their mothers are employed.” 3) “If a husband and a wife both work full-time, they should share household tasks equally.” 4) “Parents should encourage just as much independence from their daughters as their sons.” 5) “Mothers who work full-time when their youngest child is under age 5.” 6) “Mothers who work part-time when their youngest child is under age 5.” Dummy variables: both spouses egalitarian; both spouses moderate; both spouses traditional; wives have more egalitarian views than their husbands; husbands have more egalitarian views than their wives. Both spouses sharing traditional views is the reference category. Control variables Age of the youngest child living in the household Dummy variables: the presence of the youngest child under six years old living in the household; children aged between six and twelve years old; children aged between thirteen and seventeen years old; and childless couples (couples who have no children living in the household, or the youngest child living in the household is at least 18 years old). Childless couples are the reference category. Husbands’ work hours Husbands’ hours worked in the previous week if that is the usual number of hours worked; usual hours worked per week if otherwise. Duration of marriage Continuous measure, in years, of the length of a couple’s marriage until the date of the interview. I used a logarithmic transformation due to its skew. Age at marriage Dummy variables: both spouses were younger than 20 when married; the wife, but not the husband, was less than 20 when married; the husband, not the wife, was less than 20 when married; and both spouses married at age 20 or older. Both spouses marrying at age 20 or older is the reference category. Wives’ education Dummy variables: wife has less than a high school diploma; wife has a high school diploma; wife has some college; wife has a college degree or above. Wife having a college degree or above is the reference category. Husbands’ education relative to wives’ education Continuous variable measured by the difference between husbands’ and wives’ education in degree. Marital order Dummy variables: both spouses are in their first marriage; both spouses are remarried; husband is in his first marriage, and wife is remarried; wife is in her first marriage, and husband is remarried. Both spouses being in their first marriage is the reference category. Race-ethnicity Dummy variables: both spouses are White; both spouses are Black; both spouses are Hispanic; spouses are from different races. Both spouses being White is the reference category. Total income of the household Dummy variables: total income is $30,000 or less; between $30,001 and $50,000; or over $50,000. A total income of over $50,000 is the reference category. The following question was administered to the primary re- spondent and spouse: “How many hours do you usually work per week?” This variable was treated as continuous. To test the nonlinear effect of wives’ work hours, I coded this variable into four dummies: not employed (0 hours), part time (less than 35 hours), full time (between 35 and 40 hours), and overtime (more than 40 hours per week). The results showed that there is a linear effect; thus, I continued to treat wives’ work hours as continuous. Wives’ work hours were centered (deviated from the mean), and I then created multiplicative interaction terms to examine the hypothesized moderator effects. This approach reduces multi-colinearity among the predictors (Aiken & West, 1991) and aids in the interpretation of results (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Marital Interaction Marital interaction was measured by asking the primary re- spondent and spouse how often they spend time alone together (1 = never to 6 = almost every day). Among both genders, 75 percent reported spending time with their spouses almost every day. With such a skewed distribution, I create a dummy vari- able that coded 1 for the response, “almost every day,” and 0 otherwise for both genders. Spending time with a spouse almost every day was coded as high marital interaction, and spending time with a spouse less often was coded as low marital interac- tion. I then created a couple-level measure of marital interaction with four dichotomous variables (see Table 1). Gender Ideology Both the primary respondents and their spouses were asked how much they agreed with six statements measuring gender ideology. Each item was coded so that higher scores indicated a more egalitarian gender ideology. The indicators were stan- dardized and totaled to create a continuous gender ideology  D. YUCEL index for husbands and wives, respectively. The scale ranged from –13.69 to 8.84 for wives and from –12.55 to 10.41 for husbands. The alpha level was .67 for wives and .65 for hus- bands. Since the gender distribution was almost normal for both gender ideology scales, I divided this index into three equal parts: the lowest third was traditional, the middle third was a transitional (moderate) gender ideology, and the highest third represented an egalitarian gender ideology (Greenstein, 1995). I created a couple-level measure of gender ideology with five dichotomous variables (see Table 1). Control Variables Several control variables were selected based on their asso- ciation with wives’ work hours and marital dissolution in ear- lier empirical studies. They include: age of the youngest child living in the household, husband’s work hours, log of marital duration, age at marriage, wife’s education, husband’s educa- tion relative to his wife’s, marital order, race-ethnicity, and total household income (see Table 1). Results Descriptive Findings Table 2 displays the means and standard deviations for the variables in this analysis for two subsamples: couples who re- mained married and couples who separated or divorced. Twelve percent of marriages ended in separation or divorce between Waves 1 and 2 (N = 555). The table shows t-tests for continu- ous variables and chi-square tests for the categorical variables, to test whether the means and distributions in these groups were significantly different. Table 2. Descriptive statistics of independent variables in the analysis. Still married at Wave 2 Divorced or separated at Wave 2 Mean Standard deviation Mean Standard deviation Independent variables Wives’ work hours 21.46*** 20.31 25.46*** 19.85 Marital interaction Both spouses have high marital interactiona 0.38*** 0.49 0.22*** 0.42 Both spouses have low marital interaction 0.34*** 0.47 0.47*** 0.50 Husbands have low and wives have high marital interaction 0.16 0.37 0.14 0.34 Wives have low and husbands have high marital interaction 0.12*** 0.32 0.17*** 0.37 Gender ideology Both spouses are traditionalb 0.21*** 0.40 0.12*** 0.32 Both spouses are moderate 0.13 0.34 0.11 0.32 Both spouses are egalitarian 0.17* 0.38 0.22* 0.41 Wives with a more egalitarian ideology than their husbands 0.23*** 0.42 0.31*** 0.46 Husbands with a more egalitarian ideology than their wives 0.26 0.44 0.24 0.43 Control variables Age of youngest child living in the household No children presentc 0.44*** 0.50 0.28*** 0.45 Youngest child under 6 years old 0.30*** 0.46 0.44*** 0.50 Youngest child between 6 and 12 years old 0.17* 0.37 0.21* 0.40 Youngest child between 13 and 17 years old 0.09 0.29 0.07 0.26 Husbands’ work hours 36.86*** 19.71 41.24*** 17.20 Marital duration (log) 2.60*** 0.01 1.98*** 0.03 Age at current marriage Both over 20d 0.68*** 0.47 0.60*** 0.49 Both younger than 20 0.12 0.33 0.14 0.35 Spouses are not the same age 0.20** 0.40 0.26** 0.44 Wives’ education Wife has college degree or abovee 0.23** 0.42 0.19** 0.39 Wife has some college 0.21 0.41 0.20 0.40 Wife is a high school graduate 0.40 0.49 0.42 0.49 Wife has less than a high school diploma 0.16 0.37 0.19 0.40 Husbands’ education relative to wives’ education 0.07 0.98 0.05 1.04 Marital order Both spouses in first marriagef 0.71*** 0.45 0.58*** 0.49 Both spouses not in first marriage 0.12*** 0.32 0.20*** 0.40 Husband in first marriage, wife not 0.08 0.27 0.10 0.30 Wife in first marriage, husband not 0.09** 0.29 0.12** 0.33 Race-ethnicity Both spouses Whiteg 0.83** 0.37 0.79** 0.40 Both spouse Black 0.09* 0.28 0.12* 0.32 Both spouses Hispanic 0.05 0.21 0.04 0.20 Spouses not in the same racial-ethnic group 0.03** 0.17 0.05** 0.22 Total household income Total Income is over $50,000h 0.22 0.41 0.20 0.39 Total Income is $30,000 or less 0.46** 0.50 0.53** 0.50 Total Income is between $30,001 and $50,000 0.32* 0.46 0.27* 0.44 Total N 3936 3936 555 555 Based on one of the imputed data sets (N = 4491). I reported t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for the categorical variables. Letter superscripts show the eference group for each variable. ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed test). r Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 217  D. YUCEL Compared to stable married couples, divorcing couples av- eraged longer weekly work hours and were more likely to re- port low marital interaction (both spouses and wives only) and egalitarian views (both spouses and wives only). These results support this study’s hypotheses. Divorcing couples were more likely to be low-income, remarried, heterogamous in terms of race and age, and have preschoolers in the household; they were also more likely to have been married for fewer years at Wave 1 and to include wives with less education. These de- scriptive characteristics are consistent with theoretical argu- ments and previous research findings. In what follows, I exam- ine these relationships in a multivariate context. Logistic Models Because the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable (1 = separated or divorced, 0 = remained married), all the models were estimated using logistic regression. Table 3 displays the unstandardized logistic regression coefficients and odd ratios (calculated as ex). Hypothesis 1: Wives’ Work Hours and Marital Dissolution The bivariate logistic regression between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution (not shown) shows a positive and sig- nificant association between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution. For instance, wives who work 40 hours per week are around 49 percent [100*(e(.010*40) – 1)] more likely to dis- solve their marriages than those who do not work at all (p < .001). Net of all the couple-level control measures, the posi- tive association between wives’ work hours and marital disso- lution is still significant, but the coefficient size and the sig- nificance levels are reduced (Model 1). After this adjustment, wives who work 40 hours per week are around 27 percent [100*(e(.006*40) – 1)] more likely to dissolve their marriages than those who do not work at all (p < .05). All the control variables Table 3. Unstandardized coefficients for the logistic regression of wives’ work hours, marital interaction, gender ideology and control variables on marital dissolution (N = 4491). Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Logit Odds Logit Odds Logit Odds Logit Odds Logit Odds Wives’ work hours 0.006* (0.003) 1.01 0.004 (0.003) 1.00 0.004 (0.003) 1.00 0.003 (0.008) 1.00 0.003 (0.003) 1.00 Marital interaction Both low marital interaction 0.678*** (0.136) 1.97 0.670*** (0.136) 1.95 Husband low, wife high marital interaction 0.189 (0.165) 1.21 0.179 (0.166) 1.20 Husband high, wife low marital interaction 0.694*** (0.159) 2.00 0.684*** (0.160) 1.98 Gender ideology Both moderate 0.191 (0.203) 1.21 0.196 (0.211) 1.22 0.171 (0.204) 1.19 Both egalitarian 0.475** (0.184) 1.61 0.579** (0.198) 1.78 0.482** (0.186) 1.62 Wives with more egalitarian views than their husbands 0.555*** (0.170) 1.74 0.556** (0.179) 1.74 0.519** (0.171) 1.68 Husband with more egalitarian views than their wives 0.274 (0.176) 1.31 0.279 (0.192) 1.32 0.241 (0.177) 1.27 Wives’ hours* both moderate 0.006 (0.011) 1.01 Wives’ hours* both egalitarian –0.008 (0.011) 0.99 Wives’ hours* wives with more egalitarian views than their husbands 0.003 (0.009) 1.00 Wives’ hours* husbands with more egalitarian views than their wives 0.002 (0.010) 1.00 Intercept –0.841*** –0.960*** –1.247*** –1.252*** –1.352*** –2 Log Likelihood 1485.206 1467.789 1477.293 1475.010 1460.543 χ2 388.842*** 423.676*** 404.670*** 409.234*** 438.168*** DF 20 23 24 28 27 Pseudo-R2 0.12 0.13 0.12 0.12 0.13 Standard errors are in parentheses. All models include the following control variables (not shown): age of the youngest child living in the household, husbands’ work hours, log of marital duration, age at marriage, wives’ education, husbands’ education relative to wives’, marital order, race-ethnicity, and total household income.***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed test). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 218  D. YUCEL operated in the expected direction. Model 1 supports the first hypothesis that there is a positive and significant relationship between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution; this asso- ciation holds net of all controls. Hypothesis 2: The Mediating Effect of Marital Interaction Model 2 tested the mediating effect of marital interaction us- ing the attachment hypothesis. Controlling for marital interac- tion, the effect of wives’ work hours is no longer significant, which suggests that couples’ marital interaction mediates this effect. When both spouses report low marital interaction and when only wives report low marital interaction, couples are about twice as likely to dissolve their marriages (p < .001). In contrast, when only husbands report low marital interaction, couples are not significantly more likely to dissolve their mar- riages than are spouses who both report high marital interaction. In addition, marital interaction measures fully mediate the ef- fect of the presence of a child under 6 years old and partially mediate the effect of a child between 6 and 12 years old on marital dissolution (not shown in Table 3). Once I added the marital interaction measures, couples with a preschooler living in the household were no longer more likely to dissolve their marriages. Furthermore, couples with children between 6 - 12 years old were about 39 percent more likely to dissolve their marriages than childless couples, but the significance effect was reduced (p < .05; not shown). Model 2 shows that the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution operates through de- creased marital interaction (for both spouses and wives only). Hypothesis 2 is therefore supported, and the inclusion of mari- tal interaction dummies significantly improves the previous model (chi-square change between Model 1 and Model 2 = 34.83 with 3 df, p < .001). Hypothesis 3: The Mediating Effect of Gender Ideology Model 3 tested the additive effect of gender ideology and supported the gender role strain hypothesis. When the model controlled for couple-level control variables and couples’ gen- der ideology, the effect of wives’ work hours was no longer significant. This finding suggests that the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution is mediated by couples’ gender ideology. Specifically, the effect of wives’ increased work hours on marital dissolution operates through increased egali- tarianism (for both spouses and wives only), which is consistent with the gender role strain argument. Couples’ gender ideology dummies mediate the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution (as shown in Model 3). Couples who share an egalitarian perspective are around 61 percent more likely to end their marriages than spouses with a traditional outlook (p < .01), while couples in which wives have a more egalitarian view- point than their husbands are about 74 percent more likely to end their marriages than couples who share a traditional view- point (p < .001). The effects of the other control variables re- main the same as in Model 1. The pseudo R-square also re- mained the same, but the chi-square change between Model 1 and Model 3 was 15.83 with 4 df and is significant (p < .01). Thus, the inclusion of the additive effects of gender ideology improved on Model 1, and Hypothesis 3 was supported. Con- sistent with the role strain theory, gender egalitarianism (for both spouses and wives only) mediates the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution. Hypothesis 4: The Moderating Effect of Gender Ideology To test the multiplicative effect of gender ideology, Model 4 included the interaction terms between wives’ work hours and gender ideology variables. None of the interactions between gender ideology and wives’ work hours were significant. I can therefore conclude that the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution does not differ across couples’ gender ide- ology. The chi-square change between Model 3 and Model 4 was 4.56 with 4 df and is not significant. The insignificant in- teraction terms between wives’ work hours and gender ideology did not improve on the previous model. Thus, the interaction terms between wives’ work hours and gender ideology dum- mies were excluded from the subsequent analyses. Overall, this result does not support the ideological consistency hypothesis, and Hypothesis 4 is not supported. Hypothesis 5: Comparison of Wives’ or Husbands’ Assessments of Their Relationship in Predicting Marital Dissolution among Couples with Inconsistent Reports I included marital interaction and gender ideology dummies in the final model, Model 5. The inclusion of these variables significantly improved Model 3 (chi-square change between Model 3 and Model 5 = 33.50 with 3df, p < .001). This model shows that the simultaneous inclusion of marital interaction measures and gender ideology measures added significantly to our prediction of marital dissolution. Model 5 shows that cou- ples who share egalitarian ideas and couples with more egali- tarian wives are around 62 and 68 percent (respectively) more likely to dissolve their marriages, compared with spouses who share a traditional outlook (p < .01). In addition, spouses who both report lower marital interaction and couples in which only the wife reports low marital interaction are around twice as likely to dissolve their marriages than spouses who both give reports of high marital interaction (p < .001). Sometimes couples give different reports of relationship as- sessment. For couples who evaluate their marriages differently, is marital dissolution equally affected by the husbands’ and wives’ reports? In addition, is marital dissolution equally af- fected when husbands report more egalitarianism (than their wives) versus when wives report more egalitarianism (than their husbands)? This study’s results suggest that when wives report low levels of marital interaction, marital dissolution is more likely. However, when husbands report low levels of marital interaction, marital dissolution is more likely only when their wives agree. Similarly, when wives report egalitarian gender roles, regardless of their husbands’ gender roles, marital dissolution is more common. In contrast, a husband’s egalitar- ian gender ideology is only a significant predictor of marital dissolution when his wife also espouses an egalitarian gender role. Overall, when there is inconsistency between spouses’ reports, the effect of relationship assessment on marital dissolu- tion is contingent on gender. This finding signals the impor- tance of wives’ assessments of their relationships on marital dissolution. Thus, Hypothesis 5 is supported. Discussion and Conclusion Despite inconsistent findings, some prior research has con- cluded that wives’ work hours are correlated with higher mari- tal dissolution. However, researchers have not yet clarified the underlying mechanisms that link wives’ work hours to marital dissolution. The results in this study suggest that wives’ in- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 219  D. YUCEL creased work hours are positively correlated with higher marital dissolution. In addition, the effect of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution operates through low marital interaction (for both spouses and for wives only). This study also found that the effect of wives’ increased work hours on marital dissolution is mediated through higher gender egalitarianism (for both spouses and for wives only). Lastly, the results suggest the im- portance of women’s assessment of their relationships on mari- tal dissolution. Specifically, this study concludes that, among couples with different perceptions of their marriages, wives’ assessments of low marital interaction and egalitarian gender ideology both predict marital dissolution, and that husbands’ assessments alone have no significant effect. One of the most rapid changes since the twentieth century in the United States has been the substantial increase in married women’s participation in the labor force. About 60 percent of all women are in the labor force, compared with nearly 75 per- cent of all men (US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2008). Researchers have long studied wives’ em- ployment, which has been considered a determinant of marital instability. This study extends and enriches the existing litera- ture in two important ways, by testing some of the mediating and moderating mechanisms to better understand this relation- ship. The results emphasize the importance of attachment hy- pothesis and role strain theory. First, this study found that mar- riages face the challenges of the time factor (i.e., reduced time for marital interaction) associated with wives’ employment and of changes in gender ideologies as more women participate in the labor force. Second, this study builds upon prior studies by using couple-level measures and data from both husbands and wives. In doing so, this study differentiates the effects of each spouse’s views on marital dissolution when there is either con- sistency or inconsistency between couples’ reports of gender ideology and marital interaction. The results suggest that per- ceptions of marriages vary between husbands and wives. Therefore, this study suggests the importance of future research taking the relative characteristics of husbands and wives into account. Despite these contributions, this study also has some limita- tions. Although the results suggest that wives’ increased work hours outside the home might decrease marital interaction and increase gender egalitarianism, I cannot make a causal argu- ment about these correlations because the variables for wives’ work hours and gender ideology were both measured at the same time. Greene and Quester (1982) also found that women who think about divorce are more likely to be in the labor force and to work more hours than women who do not think about divorce. I would need more than two waves of data to rule out the causal role of wives’ work hours on marital dissolution. Thus, the results presented in this study should be classified as “correlates” and not true “causes” of marital dissolution. This study has opened new avenues for future research. For example, would a sample of first-marriage couples who have been married for a short duration yield the same results? Cou- ples who are older, have been married for a long time, and are in their first marriages are less likely to divorce overall, and may be less affected by variations in wives’ work hours. Over- all, the results do not suggest that these are the only two mechanisms that explain this association between wives’ in- creased work hours and marital dissolution. For example, the time constraints associated with wives’ work hours might also create stress associated with not having enough time for child care and housework. This stress leads to weaker perceptions of marriage and thus increases the likelihood of martial dissolution. On the other hand, wives’ increased gender egalitarianism might lead them to perceive their marriages as unfair; this per- ception lowers marital quality and increases the risk of marital dissolution. Future research could also consider the mediating and/or moderating effects of other indicators such as wives’ education (Bumpass, Sweet, & Cherlin, 1991), wives’ econo- mic resources (Teachman, 2010) and work schedule (Kalil, Ziol- Guest, & Epstein, 2010; Kingston & Nock, 1987; Presser, 2000; White & Keith, 1990), the division of household labor (Cun- ningham, 2007), and perceptions of fairness within the marriage (Blair, 1993; Greenstein, 1996a). These analyses would shed additional light on the conditions under which wives’ work hours predict marital dissolution. The same question could also be explored using the third wave of the NSFH. Studies might investigate data on married couples at Wave 1 and changes in employment, marital interaction, and gender ideology between the first two waves, and analyze the effects of these changes on marital outcomes in Wave 3. These analyses would be able to test causality and permit researchers to examine whether the adverse effects of wives’ work hours may have decreased in recent years. However, given the attrition from the third wave, the serious limitations of the NSFH data set may be exacerbated in future waves of data. These results suggest that the relational tensions associated with wives’ increased work hours and the associated gender egalitarianism explain some of the relationships between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution. As more women join the labor force, dual-earner families will face more challenges, such as time constraints and ideological change. Although it should be noted that the husbands of employed women and of egalitarian wives participate in more housework and child care (Orbuch & Eyster, 1997; Pleck, 1985; Presser, 1994) and that there is near equality in spouses’ employment statuses, the di- vision of domestic labor (e.g., the household division of labor and child care) is far from equal (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000). It is still the case that, in response to wives’ employment change, husbands increase their participation in domestic work much less than wives decrease theirs. This find- ing indicates that there is a lag in husbands’ adaptation to the change in their wives’ employment status (i.e., when wives enter full-time, paid work) (Gershuny, Bittman, & Brice, 2005). Overall, wives might still experience time pressure and the need to balance work and family roles. This finding indicates that husbands need to take on more of the responsibilities that are traditionally associated with women, such as housework and child care. Unless these adaptations take place, it is possible that wives will be less satisfied in their marriages, which de- creases marital interaction and increases the likelihood of mari- tal dissolution. This study emphasizes the time factor of wives’ employment, which is found to predict marital dissolution. This factor leads not only to decreased marital interaction but also may cause stress, especially for wives, associated with the need to balance work and family roles. Thus, as more women join the labor force, employers might provide family-friendly benefits, such as emergency child-care, to reduce some of the negative con- sequences of these time constraints. Moreover, these results also suggest that spouses’ relationship assessments differ. Thus, it is important for future studies of relationship outcomes to include information from both husbands and wives, not just Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 220  D. YUCEL information from one spouse. There has indeed been extensive research on the question of how wives’ work hours may be linked to marital dissolution. Still, this study takes an important step forward by emphasizing that more research is needed to better understand the mediating and moderating mechanisms between wives’ work hours and marital dissolution. In addition, this study’s use of data sets such as the NSFH that collect data from both spouses, and its measurement approaches to capture consistency as well as con- flict between spouses’ views, is critical to further improving research in this area. Acknowledgements I appreciate the comments of Dr. Douglas Downey, Dr. Mar- garet Gassanov, and Dr. Donna Bobbitt-Zeher. REFERENCES Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Amato, P. R., Johnson, D. R., Booth, A., & Rogers, S. J. (2003). Con- tinuity and change in marital quality between 1980 and 2000. Jour- nal of Marriage and Famil y, 65, 1-22. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00001.x Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in gender division of labor. So- cial Forces, 79, 191-228. Blair, S. L. (1993). Employment, family, and perceptions of marital quality among husbands and wives. Journal of Family Issues, 14, 189-212. doi:10.1177/019251393014002003 Bolzendahl, C. I., & Myers, D. J. (2004). Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: Opinion change in women and men, 1974-1998. Social Forces, 83, 759-790. doi:10.1353/sof.2005.0005 Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., White, L., & Edwards, J. N. (1984). Women, outside employment, and marital instability. American Journal of Sociology, 90, 567-583. doi:10.1086/228117 Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The signify- cance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Mar- riage and the Family, 62, 833-846. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00833.x Bumpass, L., Sweet, J., & Cherlin, A. (1991). The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53, 913-927. doi:10.2307/352997 Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2008). Labor force participation rates, 1975-2008. URL. http://www.bls.gov/opub/working/page3b.htm Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied mul- tiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Coverdill, J. E., Kraft, J. M., & Manley, K. S. (1996). Employment history, the sex typing of occupations, pay and change in gender-role attitudes: A longitudinal study of young married women. Sociologi- cal Focus, 29, 47-60. Cunningham, M. (2007). Influences of women’s employment on the gendered division of household labor over the life course: Evidence from a 31-year panel study. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 422-444. doi:10.1177/0192513X06295198 Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: Compo- nents, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 87-105. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920 Duncan, G. J., & Hoffman, S. D. (1985). A reconsideration of the eco- nomic consequences of marital dissolution. Demography, 22, 485-497. doi:10.2307/2061584 Fan, P., & Marini, M. M. (2000). Influences on gender-role attitudes during the transition to adulthood. Social Science Research, 29, 258- 283. doi:10.1006/ssre.1999.0669 Gager, C. T., & Sanchez, L. (2003). Two as one? Couples’ perceptions of time spent together, marital quality, and the risk of divorce. Jour- nal of Family Issues, 24, 21-50. doi:10.1177/0192513X02238519 Gershuny, J., Bittman, M., & Brice, J. (2005). Exit, voice, and suffering: Do couples adapt to changing employment patterns? Journal of Mar- riage and Family, 67, 656-665. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00160.x Goode, W. J. (1960). A theory of role strain. American Sociological Review, 25, 483-496. doi:10.2307/2092933 Greenstein, T. N. (1990). Marital disruption and the employment of married women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 657-676. doi:10.2307/352932 Greenstein, T. N. (1995). Gender ideology, marital disruption, and the employment of married women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 31-42. doi:10.2307/353814 Greenstein, T. N. (1996a). Gender ideology and perceptions of the fairness of the division of labor: Effects on marital quality. Social Forces, 74, 1029-1042. Greenstein, T. N. (1996b). Husbands’ participation in domestic labor: Interactive effects of wives’ and husbands’ gender ideologies. Jour- nal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 585-595. doi:10.2307/353719 Greene, W. H., & Quester, A. O. (1982). Divorce risk and wives’ labor supply behavior. Social Scie n c e Quarterly, 63, 16-27. Heaton, T. B., & Blake, A. M. (1999). Gender differences in determi- nants of marital disruption. Journal of Family Issues, 20, 25-45. doi:10.1177/019251399020001002 Hill, M. S. (1988). Marital stability and spouses’ shared time. Journal of Family Issues, 9, 427-451. doi:10.1177/019251388009004001 Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the re- volution at home. New York, NY: Viking Penguin. Holden, K. C., & Smock, P. J. (1991). The economic costs of marital dissolution: Why do women bear a disproportionate cost?” Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 51-78. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.17.080191.000411 Huber, J., & Spitze, G. (1981). Wives’ employment, household behave- iors, and sex-role attitudes. Social Forces, 6 0, 50-69. Johnson, J. H. (2004). Do long work hours contribute to divorce? Top- ics in Economic Analysis and Policy, 4, 1-23. doi:10.2202/1538-0653.1118 Kalil, A., Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Epstein, J. L. (2010). Nonstandard work and marital instability: Evidence from the national longitudinal sur- vey of youth. Journal of Marr ia g e and Family, 72, 1289-1300. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00765.x Kingston, P. W., & Nock, S. L. (1987). Time together among dual-earner couples. American So c i ological Review, 52, 391-400. doi:10.2307/2095358 Minnotte, K. L., Minnotte, M. C., Pedersen, D. E., Mannon, S. E., & Kiger, G. (2010). His and her perspectives: Gender ideology, work- to-family conflict, and marital satisfaction. Sex Roles, 63, 425-438. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9818-y Montalto, C. P., & Gerner, J. L. (1998). The effect of expected changes in marital status on labor supply decisions of women and men. Jour- nal of Divorce and Remarriage, 28, 25-51. doi:10.1300/J087v28n03_02 Nock, S. L. (1998). Marriage in men’s lives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Nordenmark, M., & Nyman, C. (2003). Fair or unfair? Perceived fair- ness of household division of labour and gender equality among women and men: The Swedish case. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 10, 181-209. doi:10.1177/1350506803010002004 Orbuch, T. L., & Eyster, S. L. (1997). Division of household labor among black couples and white couples. Social Forces, 76, 301-332. Percheski, C. (2008). Opting out? Cohort differences in professional women’s employment rates from 1960 to 2005. American Socio- logical Review, 73, 497-517. doi:10.1177/000312240807300307 Pleck, J. H. (1985). Working wives, working husbands. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Poortman, A. (2005). How work affects divorce. The mediating role of financial and time pressures. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 168-195. doi:10.1177/0192513X04270228 Presser, H. B. (1994). Employment schedules among dual-earner spouses and the division of household labor by gender. American Sociologi- cal Review, 59, 348-364. doi:10.2307/2095938 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 221  D. YUCEL Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 222 Presser, H. B. (2000). Nonstandard work schedules and marital insta- bility. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 93-110. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00093.x Ross, H. L., & Sawhill, I. V. (1975). Time of transition: The growth of families headed by women. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Sanchez, L., & Gager, C. T. (2000). Hard living, perceived entitlement to a great marriage, and marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 708-722. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00708.x Sayer, L. C., & Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Women’s economic independ- ence and the probability of divorce: A review and reexamination. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 906-943. doi:10.1177/019251300021007005 Schmitt, M., Matthias, K., & Shapiro, A. (2007). Marital interaction in middle and old age: A predictor of marital satisfaction? International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 65, 283-300. doi:10.2190/AG.65.4.a Sen, B. (2000). How important is anticipation of divorce in married women’s labor supply decisions? An intercohort comparison using NLS data. Economics Letters, 67, 209-216. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(99)00259-1 South, S. J., & Spitze, G. (1986). Determinants of divorce over the marital life course. American Sociological Review, 51, 583-590. doi:10.2307/2095590 Spitze, G., & South, S. J. (1985). Women’s employment, time expen- diture, and divorce. Jo u r n a l o f Family Issues, 6, 307-629. doi:10.1177/019251385006003004 Sweet, J. A. & Bumpass, L. L. (2002). The national survey of families and households—Waves 1, 2, and 3: Data description and documen- tation. Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-Madison, Center for Demography and Ecology website. http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/home.htm Sweet, J., Bumpass, L., & Call, V. (1988). The design and content of the national survey of families and households. Center for Demog- raphy and Ecology, University of Wisconsin. Teachman, J. (2010). Wives’ economic resources and risk of divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 31, 1305-1323. doi:10.1177/0192513X10370108 Vere, J. P. (2007). Having it all no longer: Fertility, female labor supply, and the new life choices of generation X. Demography, 44, 821-828. doi:10.1353/dem.2007.0035 Voydanoff, P. (1988). Work role characteristics, family structure de- mands, and work/family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Fam- ily, 50, 749-761. doi:10.2307/352644 White, L., & Keith, B. (1990). The effects of shift work on the quality and stability of marital relations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 453-462. doi:10.2307/353039 Yucel, D. (2012). Wives’ work hours and marital dissolution: Differen- tial effects across marital duration. Sociology Mind, 2, 12-22.

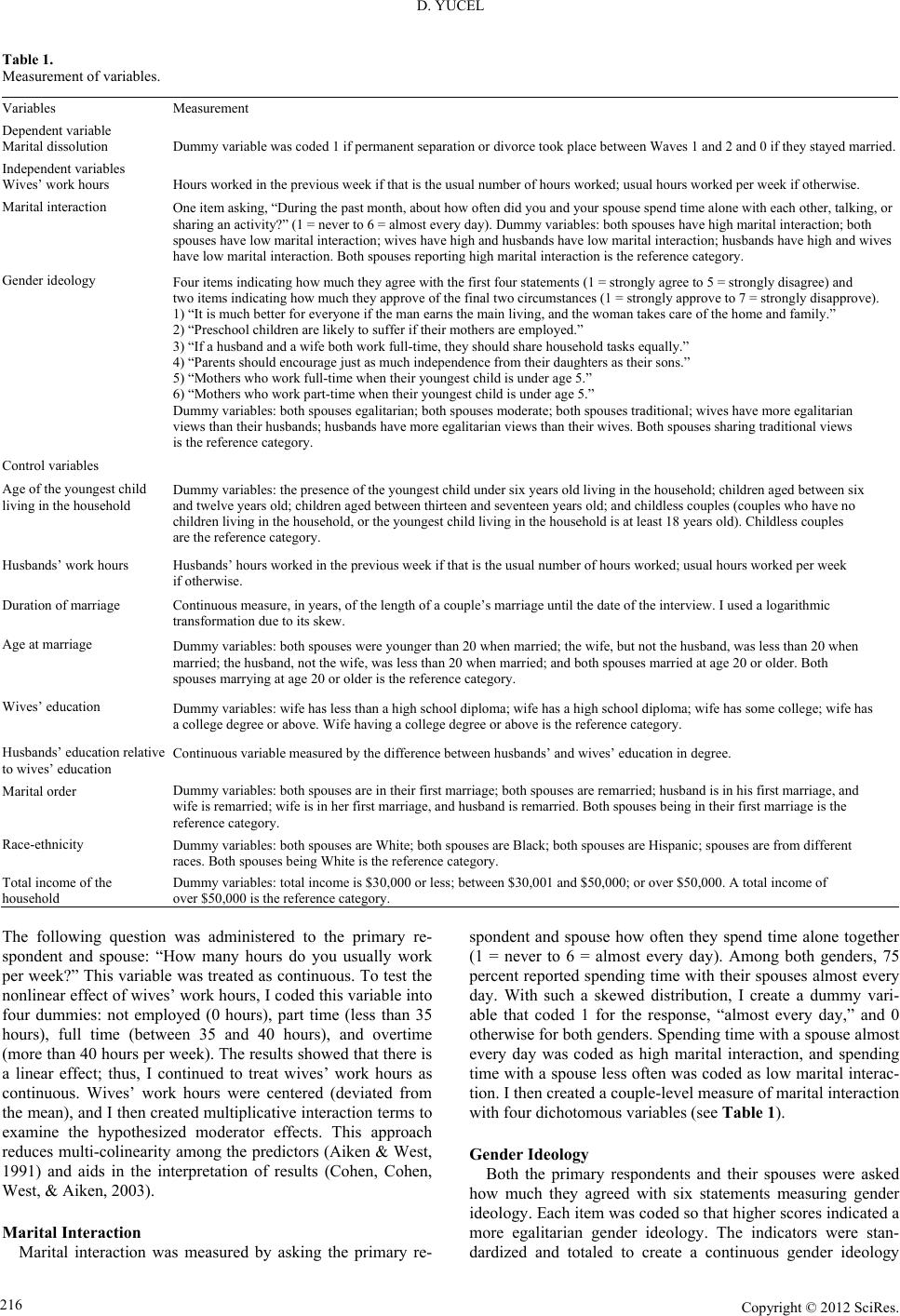

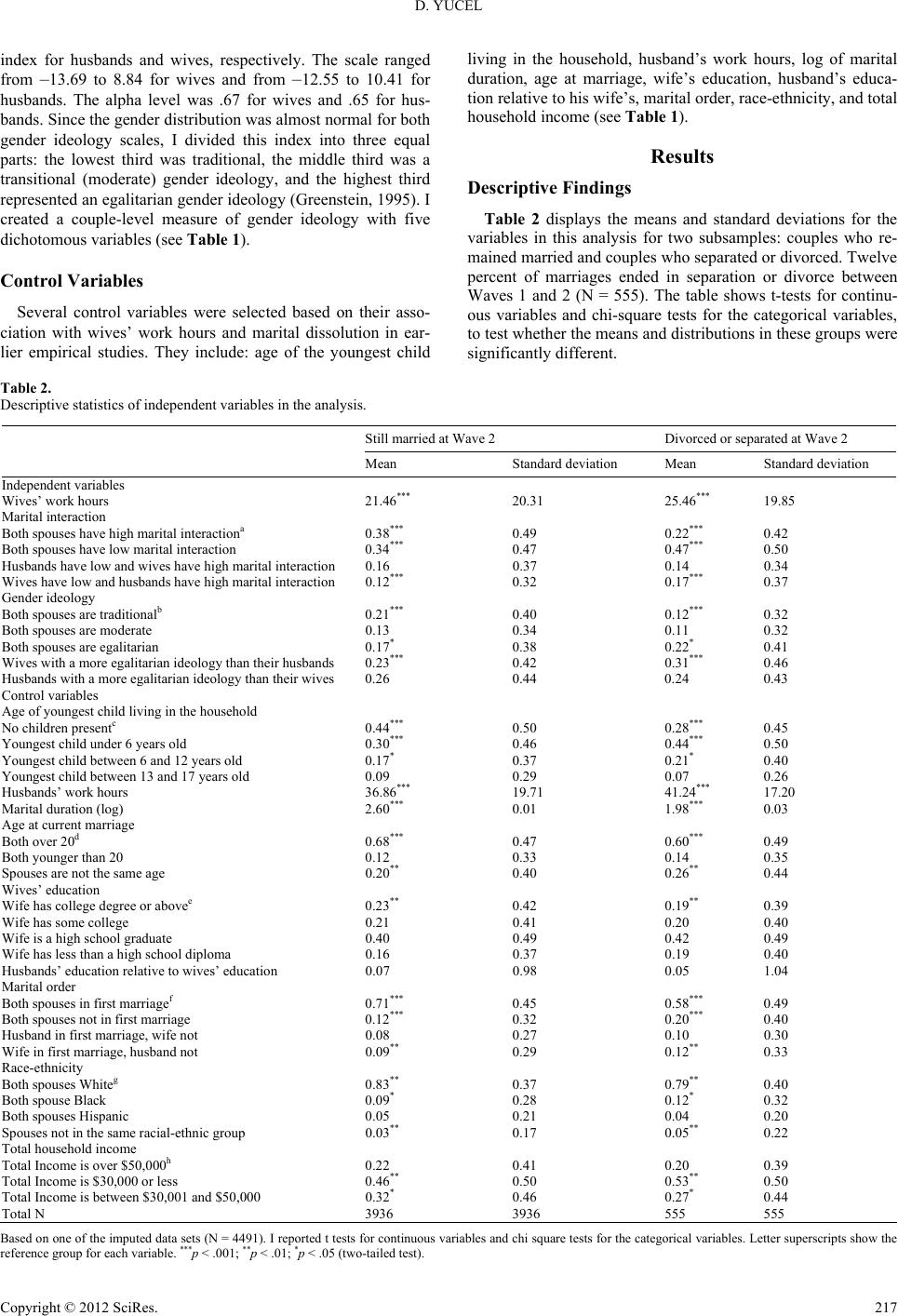

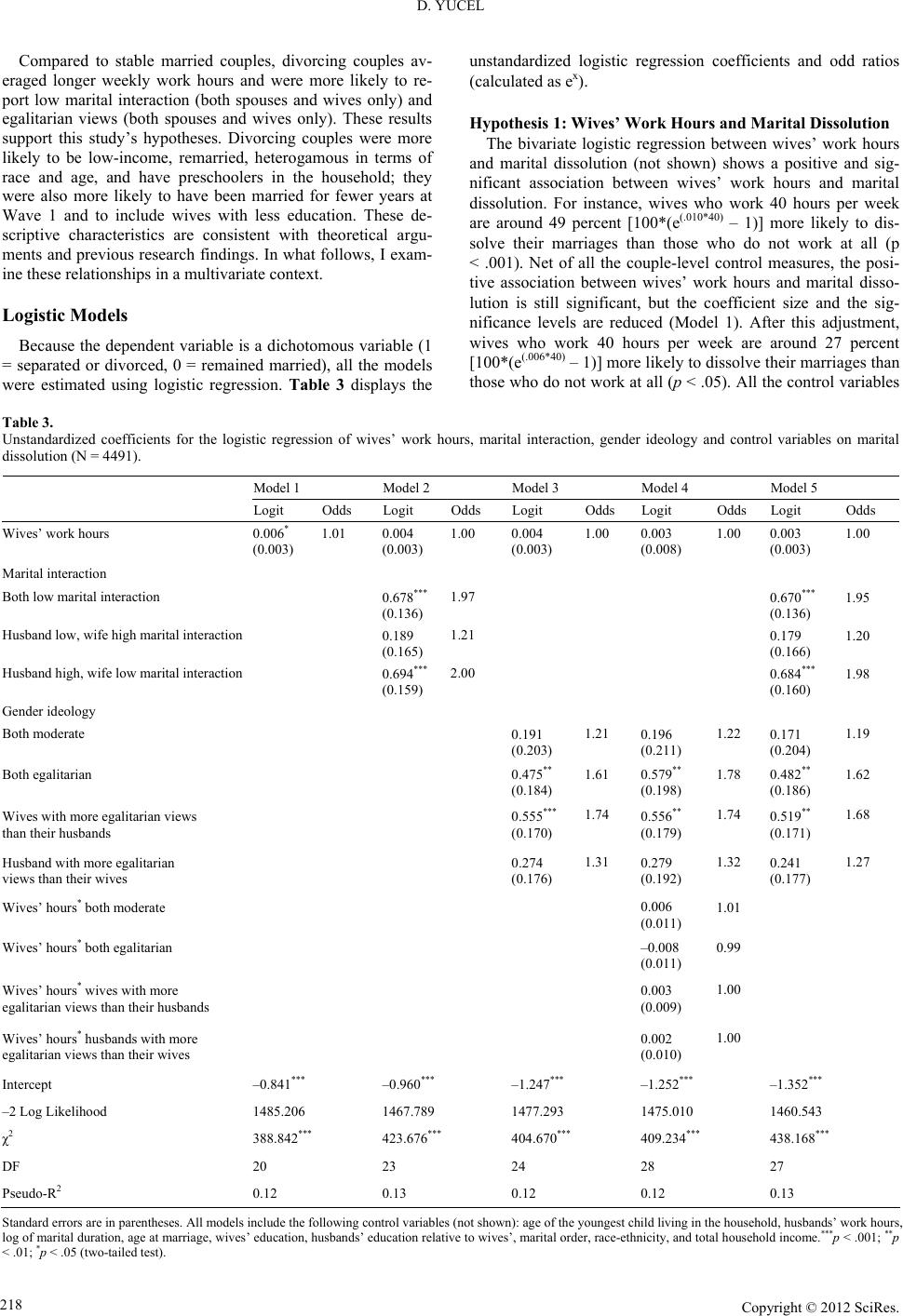

|