Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.08(2017), Article ID:77820,16 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.88087

Zeno of Elea Shines a New Light on Quantum Weirdness

María Esther Burgos

Department of Physics, University of Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: April 17, 2017; Accepted: July 18, 2017; Published: July 21, 2017

ABSTRACT

After a brief reference to the quantum Zeno effect, a quantum Zeno paradox is formulated. Our starting point is the usual version of Time Dependent Perturbation Theory. Although this theory is supposed to account for transitions between stationary states, we are led to conclude that such transitions cannot occur. Paraphrasing Zeno, they are nothing but illusions. Two solutions to the paradox are introduced. The first as a straightforward application of the postulates of Orthodox Quantum Mechanics; the other is derived from a Spontaneous Projection Approach to quantum mechanics previously formulated. Similarities and differences between both solutions are highlighted. A comparison between the two versions of quantum mechanics, supporting their corresponding solutions to the paradox, shines a new light on quantum weirdness. It is shown, in particular, that the solution obtained in the framework of Orthodox Quantum Mechanics is defective.

Keywords:

Quantum Weirdness, Quantum Measurements, Spontaneous Quantum Jumps, Time Dependent Perturbation Theory, Quantum Zeno Paradox

1. Introduction and Outlook

The Greek philosopher Zeno of Elea (ca. 490-430 BC) supported Parmenide’s doctrine. This philosophy states that, contrary to the evidence of our senses, the belief in plurality and change is mistaken; in particular motion is nothing but an illusion.

The most popular Zeno paradoxes concerning motion are “Achilles and the Tortoise” and the “Arrow Paradox”. In the latter it is assumed that for motion to occur, an object must change the position which it occupies. In the case of an arrow in flight, Zeno argues that “the flying arrow is at rest, which result follows from the assumption that time is composed of moments… he says that if everything when it occupies an equal space is at rest, and if that which is in locomotion is always in a now, the flying arrow is therefore motionless. (Aristotle Physics, 239b. 30) Zeno abolishes motion, saying ‘What is in motion moves neither in the place it is nor in one in which it is not’. (Diogenes Laertius Lives of Famous Philosophers, ix.72)” [1] .

In 1977 Baidyanath Misra and George Sudarshan studied the behavior of an unstable particle continuously observed to see whether it decays or not [2] . The resulting effect have previously been described by Alan Turing in the following terms: “it is easy to show using standard [quantum] theory that if a system starts in an eigenstate of some observable, and measurements are made of that observable N times a second, then, even if the state is not a stationary one, the probability that the system will be in the same state after, say, one second, tends to one as N tends to infinity; that is, that continual observations will prevent motion…” [3] . Initially this argument received the name of Turing paradox.

In their 1977 paper, Misra and Sudarshan referred to the behavior of a quantum system subjected to frequent ideal measurements. They considered the process of continuing observation as the limiting case of successions of (practically) instantaneous measurements as the intervals between successive measurements approach zero. They argued that, “since there does not seem to be any principle, internal to quantum theory, that forbids the duration of a single measurement or the dead time between successive measurements from being arbitrarily small, the process of continuous observation seems to be an admissible process in quantum theory” [2] . They concluded that an unstable particle which is continuously observed to see whether it decays or not will never be found to decay and named this phenomenon the quantum Zeno paradox [2] .

Misra and Sudarshan article stimulated a great deal of theoretical and experimental work. The possibility that the decay of an unstable particle could be prevented by continued observation was, however, considered an alarming result by some physicists. In particular, as early as in 1983, Mario Bunge and Andrés Kálnay explicitly dealt with the suspicion that the quantum Zeno paradox must be a fraud [4] [5] [6] .

In 1990 Wayne Itano et al. published a paper entitled Quantum Zeno effect. In its abstract they assert: “The quantum Zeno effect is the inhibition of transitions between quantum states by frequent measurements of the state. The inhibition arises because the measurement causes a collapse (reduction) of the wave function. If the time between measurements is short enough, the wave function usually collapses back to the initial state. We have observed this effect in an rf transition… Short pulses of light, applied at the same time as the rf field, made the measurements” ( [7] ; emphases added).

In 2009, Itano published a revision of different opinions regarding the quantum Zeno effect. He acknowledges that “there has been much disagreement as to how the quantum Zeno effect should be defined and as to whether it is really a paradox, requiring new physics, or merely a consequence of ‘ordinary’ quantum mechanics” [8] . For instance, according to Asher Peres, the quantum Zeno effect has nothing paradoxical: “What happens simply is that the quantum system is overwhelmed by the meters which continuously interact with it” ( [9] , p. 394).

The theoretical and experimental work dealing with the quantum Zeno effect is exciting. But its relation with Zeno’s arrow paradox is questionable: Zeno’s purpose was not to stop the flying arrow; it was to show that motion is an illusion. By contrast, both Turing’s argument and Misra and Sudarshan’s contribution aim to stop transitions between quantum states by frequent measurements; let alone the experiment by Itano et al. (and many others we have not mention for brevity) where transitions between quantum states seem to have been truly inhibited, at least partially.

Differing from other references to the quantum Zeno effect, the present paper highlights a True Quantum Zeno paradox (TQZ paradox for short): we show that the usual version of Time Dependent Perturbation Theory (TDPT) leads to the conclusion that transitions between stationary states cannot happen. They are nothing but illusions.

The outlook of this paper is as follows: In Section 2, we formulate the TQZ paradox. In Section 3 we introduce and compare two different solutions to the paradox: an orthodox solution results from a straightforward application of the postulates of Orthodox (Ordinary, Standard) Quantum Mechanics (OQM); the other is derived from a Spontaneous Projection Approach to quantum mechanics (SPA) previously formulated. Section 4 contrasts the main traits of SPA and OQM. In particular, similarities and differences between both solutions to TQZ paradox are highlighted. Section 5 sums up the conclusions of the present work.

2. Formulation of TQZ Paradox

The aim of TDPT is to calculate the transition probability between stationary states induced by a time dependent perturbation. In the following we sketch the essential features of TDPT. For more details see for instance: D. R. Bes ( [10] , Chapter IX); C. Cohen-Tannoudji et al. ( [11] , Chapter XIII); P. A. M. Dirac ( [12] , Chapter VII); W. Heitler ( [13] , Chapter IV); E. Merzbacher ( [14] , Chapter XIX); and/or A. Messiah ( [15] , Chapitre XVII). Notes: Symbols used by these authors may have been changed for homogeneity. All the states referred to in this paper are normalized.

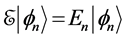

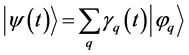

Consider a system with Hamiltonian  which does not depend explicitly on time. It will be called the unperturbed Hamiltonian of the system. Its eigenvalue equations are

which does not depend explicitly on time. It will be called the unperturbed Hamiltonian of the system. Its eigenvalue equations are

(1)

(1)

where  are the eigenvalues of

are the eigenvalues of  and

and  the corresponding eigenstates. For simplicity we assume

the corresponding eigenstates. For simplicity we assume  spectrum to be entirely discrete and non-degenerate.

spectrum to be entirely discrete and non-degenerate.

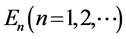

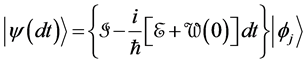

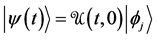

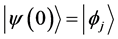

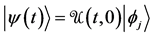

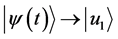

We shall suppose that at initial time  the system is in the stationary state

the system is in the stationary state . If for

. If for  the Hamiltonian were

the Hamiltonian were , the state vector at time t would be

, the state vector at time t would be

(2)

(2)

where ħ is Planck’s constant divided by  and i is the imaginary unity. The kets

and i is the imaginary unity. The kets  and

and  differ only by the global phase factor

differ only by the global phase factor . So all the kets

. So all the kets  given by Equation (2) represent one and the same eigenstate corresponding to the eigenvalue Ej.

given by Equation (2) represent one and the same eigenstate corresponding to the eigenvalue Ej.

A system in a stationary state (i.e. an eigenstate of the unperturbed Hamiltonian ) will remain in that state forever. Nevertheless, TDPT establishes that by applying a time dependent perturbation, transitions between different eigenstates of

) will remain in that state forever. Nevertheless, TDPT establishes that by applying a time dependent perturbation, transitions between different eigenstates of  can be induced and determines the probability corresponding to every particular transition.

can be induced and determines the probability corresponding to every particular transition.

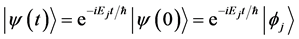

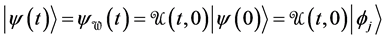

If at

The perturbation

where

Let us underline the difference between the state vector at time t when no time dependent perturbation is applied and the state vector at time t resulting from the application of

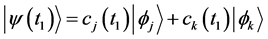

At this point the probability of a transition taking place from state

For

TDPT deals with processes having two clearly different stages [16] . In the first―during the time interval

A collapse at t implies that the process is discontinuous at this instant. Since the sum of probabilities of a transition from

there is no room for a non-null probability corresponding to a process continuous at time t.

Let us now consider the following argument:

(a) A system initially in the state

(b) The interval

(c) Taking into account the validity of Equations (5) and (6) during the interval

With the noticeable exception of Albert Messiah, neither Dirac nor any other author known to us imposes any particular condition on the interval

Let us review what happens in a small time interval

where

For

the sum of these probabilities for all

and the probability of no transition taking place at all would be

Always assuming that the process is a Schrödinger evolution during the interval

We have shown, nevertheless, that according to the usual version of TDPT the system cannot follow a Schrödinger evolution during any time interval. Therefore, the state vector at time t cannot be

3. Solving TQZ Paradox

First solution: While remaining in the framework of OQM, Messiah version of TDPT differs somewhat from the usual one. In his words: “Supposons qu’à l’instant initial

In Section 2 we pointed out that, except Messiah, neither Dirac nor any other author known to us imposes any particular condition on the interval

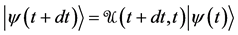

Even if the notion of instantaneous measurement is questionable ( [5] ; [17] , p. 200), Messiah successfully eludes TQZ paradox through this concept. We shall call it the orthodox solution to TQZ paradox. Figure 1 illustrates the case where the non-perturbed Hamiltonian

Figure 1. The Orthodox Solution to TQZ paradox: (a) During the first stage a Schrödinger evolution leads the state vector from

leads the state vector from

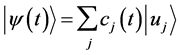

Second solution: SPA provides another solution to TQZ paradox. According to this approach [18] [19] [20] :

(i) Two kinds of processes, irreducible to one another, occur in nature: the strictly continuous and causal ones; and those implying discontinuities, where the system’s state

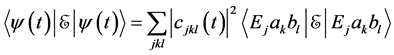

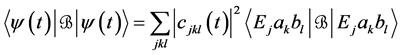

where

with probability

or

with probability

Here

and

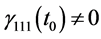

Changes (13) are projections to one of the preferential states with probabilities given by Equation (14). As

jumps like

Except (v), all these points have been introduced and discussed in previous papers [18] [19] [20] . For more details on points (ii) and (iii) leading to the definition of preferential states see Appendix A; for examples of the determination of preferential states see Appendix B.

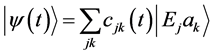

For simplicity we assume

where

If

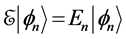

Figure 2 illustrates SPA solution in the case where the non-perturbed Hamiltonian

Differing from what happens in the framework of OQM there is always room for a Schrödinger evolution in SPA. There is, however, a complete agreement between SPA solution and orthodox solution to TQZ paradox in which concerns the ratio of probabilities corresponding to jumps to

cases it takes on the value

4. SPA versus OQM

OQM was first formulated by Dirac in 1930 [12] . It refers to individual systems and imposes two laws of change of the state vector

Figure 2. SPA Solution to TQZ paradox: (a) If no spontaneous projection happens during the time interval

conflict with the Schrödinger equation; and it implies a kind of action-at-a-dis- tance ( [17] , pp. 191-205; [20] ).

The presence in parallel of two different, irreducible to one another laws accounting for the change of the state vector

OQM marvelous success in the area of experimental predictions is mostly based on TDPT. It is agreed that the method provided by this theory must be used to solve all problems involving time, including time dependent spontaneous processes. Should TDPT be discarded, OQM and many of its extensions would lose almost completely their power of explanation and prediction [16] . At the same time, TDPT is a good example of the ambiguities OQM confronts. In Section 2 we pointed out that TDPT deals with processes having two clearly different stages [16] . In the first―during the time interval

SPA, a version of quantum mechanics previously introduced [18] [19] [20] , deals with these issues. Our motivation to formulate this approach is the restoration of philosophical realism as the basis of quantum mechanics. Albert Einstein was right when he proclaimed: “the belief in an external world independent of the perceiving subject is the basis of all natural science” [22] . We have also taken into account Bunge’s notion of epistemological realism: “The main epistemological problem about quantum theory is whether it represents real (autonomously existing) things, and therefore whether it is compatible with epistemological realism. The latter is the family of epistemologies which assume that (a) the world exists independently of the knowing subject, and (b) the task of science is to produce maximally true conceptual models of reality…” ( [17] , pp. 191-192).

Other approaches aiming to confront quantum weirdness are close to, but different from OQM. By contrast, SPA does not introduce substantial changes into the theory. It does not modify the Schrödinger equation and recovers a version of Born’s postulate where no reference to measurement is made. The exponential decay law is obtained in cases where the Hamiltonian does not depend explicitly on time [18] . Differing from OQM, SPA yields an expression for the probability of transitions to the continuum which is valid for every time and, except for some minimal restrictions, for every added potential. This prediction could be tested by experiment [19] .

It has been pointed out that some theories of spontaneous state reduction are incompatible with the attainment of equilibrium [23] . This is obviously not the case of SPA where stationary states are not only possible: they play a fundamen- tal role. We should also stress the radical difference between SPA and theories of quantum measurement based in the concept of decoherence. According to these theories, the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix should progressively vanish; it is not clear, however, why all diagonal elements but one should vanish [24] . By contrast, SPA states that a spontaneous projection to a preferential state instantaneously deletes as well the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix as all diagonal elements but one, as established by OQM when a measurement is performed.

The orthodox solution to TQZ paradox obtained in Section 3 results from a straightforward application of the postulates of OQM. But let us perform a close examination of this solution in the particular case where the perturbation ap- plied at

where

where

According to the postulates of OQM the only possible result of the measure- ment of a physical quantity is one of the eigenvalues of the operator which represents it. So a measurement of the energy performed at

By contrast, SPA solution to TQZ paradox makes no reference to measure- ments. Transitions between eigenstates of

5. Conclusions

In the framework of OQM, there are no projections without measurements. So it is necessary to invoke measurements even in spontaneous processes where measurements should obviously be absent. This is v.g. the case of absorption and emission of light and of processes occurring in semiconductors.

Both our Critical Review of TDPT [16] and the orthodox solution to TQZ paradox introduced in Section 3 highlight that in OQM the notion of measurement and consequent projections are ad-hoc. By contrast, in SPA projections are not surreptitious but explicitly included in the formalism. The same is true of the rule necessary to decide whether the system will forcibly follow a Schrödinger evolution or not. This is why SPA enjoys of a coherence which is absent from OQM [16] and allows us to provide a satisfactory solution to the True Quantum Zeno Paradox.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Professor J. C. Centeno for many fruitful discussions. We are grateful to Professors F. G. Criscuolo and Marco Ortiz Palanques for some useful comments. We thank Carlos Valero for his assistance with the figures and the transcription of formulas into Math Type.

Cite this paper

Burgos, M.E. (2017) Zeno of Elea Shines a New Light on Quantum Weirdness. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 1382-1397. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.88087

References

- 1. Huggett, N. (2010) Zeno’s Paradoxes. In: Zalta, E.N., Ed., The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2010 Edition). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 3.3 The Arrow.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/paradox-zeno - 2. Misra, B. and Sudarshan, E.C.G. (1977) Journal of Mathematical Physics, 18, 756-763.

https://doi.org/10.1063/1.523304 - 3. Teuscher, C. and Hofstadter, D. (2004) Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker. Springer, p. 54.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-05642-4 - 4. Bunge, M. and Kálnay, A.J. (1983) Il NuovoCimento, 77B, 1-9.

https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02738413 - 5. Bunge, M. and Kálnay, A.J. (1983) Il NuovoCimento, 77B, 10-18.

https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02738414 - 6. Maddox, J. (1983) Nature, 306, 111.

https://doi.org/10.1038/306111a0 - 7. Itano, W.M., Heinzen, D.J., Bollinger, J.J. and Wineland, D.J. (1990) Physical Review A, 41, 2295-2300.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.41.2295 - 8. Itano, W.M. (2009) Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 196, 012018.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/196/1/012018 - 9. Peres, A. (1993) Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht-Boston-London.

- 10. Bes, D.R. (2004) Quantum Mechanics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-05384-3 - 11. Cohen-Tannoudji, C., Diu, B. and Laloë, F. (1977) Quantum Mechanics. John Wiley & Sons, New York-London-Sydney-Toronto.

- 12. Dirac, P.A.M. (1958) The Principles of Quantum Mechanics. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 13. Heitler, W. (1984) The Quantum Theory of Radiation. Dover Publications Inc., New York.

- 14. Merzbacher, E. (1961) Quantum Mechanics. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 15. Messiah, A. (1965) Mécanique Quantique. Dunod, Paris.

- 16. Burgos, M.E. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 1449-1454.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.712132 - 17. Bunge, M. (1985) Treatise on Basic Philosophy, Vol. 7, Philosophy of Science & Technology. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht-Boston-Lancaster.

- 18. Burgos, M.E. (1998) Foundations of Physics, 28, 1323-1346.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018826910348 - 19. Burgos, M.E. (2008) Foundations of Physics, 38, 883-907.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10701-008-9213-5 - 20. Burgos, M.E. (2015) The Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics Revisited. In: Pahlavani, M., Ed., Selected Topics in Applications of Quantum Mechanics, INTECH, Croatia, 137-173.

https://doi.org/10.5772/59209 - 21. Bell, M., Gottfried, K. and Veltman, M. (2001) John S. Bell on the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Word Scientific, Singapore.

- 22. Einstein, A. (1931) James Clerk Maxwell: A Commemoration Volume. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 23. Ballentine, L.E. (1991) Physical Review A, 43, 9-12.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.43.9 - 24. Laloë, F. (2001) American Journal of Physics, 69, 655-701.

https://doi.org/10.1119/1.1356698 - 25. Burgos, M.E. (1994) Physics Essays, 7, 69-71.

https://doi.org/10.4006/1.3029115 - 26. Burgos, M.E. (1997) Speculations in Science and Technology, 20, 183-187.

- 27. Burgos, M.E., Criscuolo, F.G. and Etter, T. (1999) Speculations in Science and Technology, 21, 227-233.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005552504638 - 28. Criscuolo, F.G. and Burgos, M.E. (2000) Physics Essays, 13, 80-84.

https://doi.org/10.4006/1.3025430 - 29. Burgos, M.E. (2010) Journal of Modern Physics, 1, 137-142.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2010.12019

Appendix A: The Concept of Preferential States

Let

and

the state vector

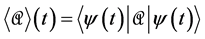

In addition to the problems referred to in Section 4, OQM conflicts with con- servation laws. Let us briefly review this issue which has been largely ignored [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] . By definition the mean value (also called expectation value) of

In Schrödinger evolutions the validity of Equation (A1) and (A2) ensures that

It has been shown that in processes involving projections (like OQM mea- surement processes) the mean value

and ending at tf which yields

many times is close to zero [29] . These remarks justify the adoption of a postulate ensuring the statistical sense of conservation laws [18] [19] [20] .

Let us consider a set of

where

for the state

If there is a unique set of

where

we shall say that

The concept of preferential states plays a paramount role in SPA for

Appendix B: Some Examples

(a) The simplest case is that where the Hamiltonian

Since

is valid, the requirement (III) established in Appendix A is satisfied for every

where

(b) We assume that the operators

and

are satisfied for

condition (III) stated in Appendix A is fulfilled for every state of the system. In the particular case where the state vector at t0 is

where

(c) We assume, as in case (b), that

while in the basis of the latter we have

Collapses to the vectors of the basis