Journal of Environmental Protection

Vol. 3 No. 8A (2012) , Article ID: 21766 , 13 pages DOI:10.4236/jep.2012.328107

Hydrodynamic Modeling of the Gulf of Aqaba

![]()

1Geotechnical and Heavy Civil Engineering Department, Dar Al-Handasah (Shair and Partners), Cairo, Egypt; 2Hydraulics Research Institute, National Water Research Center, Qalyubia, Egypt; 3Department of Irrigation and Hydraulics, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Senior Environmental Engineer, Resources and Environment Department, Dar Al-Handasah (Shair and Partners), Cairo, Egypt; 4Irrigation and Hydraulic Department, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt and Principal, Resources and Environment Department, Dar Al-Handasah (Shair and Partners), Cairo, Egypt.

Email: *mohammed.abou-elhaggag@dargroup.com

Received May 7th, 2012; revised June 6th, 2012; accepted June 30th, 2012

Keywords: 3D hydrodynamic Simulations; Gulf of Aqaba; Circulation; Delft-3d; Desalination

ABSTRACT

The Gulf of Aqaba (GOA) is unique as it contains significant percentage of the world’s natural marine biodiversity. This unique environment is potentially vulnerable to pollution particularly at its northern tip. One of the major activities affecting the environment of the gulf is the man-made desalination plants that abstract sea water and dispose desalinated brine. In this context, the paper discusses the impact of the abstract and disposal activities on the GOA environment. A 3D hydrodynamic model was developed to cover the GOA. Relevant data were collected for 3D hydrodynamic modeling construction. Delft-3D model developed by Deltares was applied in this study. The 3D model reliability was confirmed since the model results have revealed the existence of a structure of primary eddies along the axis of the Gulf which was previously reported by different researchers. Further numerical simulations were carried out by incorporating various alternatives of seawater abstraction and desalinated brine disposal off the north and north east coast of the GOA. The developed GOA hydrodynamic model, at the present stage, is preliminary where the results provide qualitative assessment on the potential impacts on the water circulation. Accordingly, this study is considered a pace ahead for a better model development and validation in the future studies.

1. Introduction

The Gulf of Aqaba (GOA) is one of the two narrow northward Gulfs of the Red Sea. It is located within 34˚20' - 35˚00'E and 27˚54' - 29˚35'N (Figure 1). It is 180 km long, 14 - 26 km wide, and has an average area of 3300 km2 and average water depth of 800 m. The maximum depth of the gulf approaches 1800 m. The Gulf is part of the Syrian-African rift valley and is flanked by mountains and desert on both the east and west sides. The southern end of the Gulf is separated from the Red Sea by a shallow sill (maximum depth 270 m) at the Straits of Tiran [1]. GOA is of interest because it hosts an ecological system that includes coral reefs and other tropical biotathat are unique in such high latitudes [2]. The climate of this region is arid with an average net evaporation of 5 - 10 mm/day [3] and with no permanent rivers flowing into the Gulf. As a result, the waters of the Gulf are among the most saline in the world, with typical salinity values of 40.5 × 103 parts per million (ppm) or more. Throughout the year, the wind blows predominantly from the north (over 90% of the time), which further enhances the evaporation and the resulting thermocline circulation. The consensual view of the general circulation in the Gulf, as described by [4] and cited in numerous studies thereafter (e.g., [1,5-10]) is that throughout the year, the net buoyancy loss due to large evaporation and heat loss drives an inverse estuarine circulation, causing a northward flow of warm and low-salinity surface water from the Red Sea into the Gulf. As the surface water flows northward, it becomes denser through cooling and evaporation. When the water reaches the northern end of the Gulf, it sinks and returns to the Red Sea as a dense layer, out flowing in the lower level of the Straits of Tiran.

Studies of the Straits of Tiran indeed mention a twolayer exchange flow [11-13], with relatively light Red Sea water entering the Gulf through the upper 80 - 90 m of the water column [12], and denser Gulf water flowing out through the bottom layer. However, all of these studies were conducted for short periods of time during the winter months. Thus the seasonal changes in the exchange flux remain unknown.

Being a semi-enclosed basin, GOA is potentially vulnerable to pollution, particularly at its northern tip.

Figure 1. Location map and bathymetry of the entire Red Sea (left panel) and the GOA (right panel). Bathymetry data is extracted from the global bathymetry dataset for the world ocean “GEBCO_08”.

Therefore, any coastal activities at this coastal region of the Gulf should be carefully investigated to examine their impact on the current conditions. The hydrodynamics of GOA was previously investigated through field observations and development of 2D hydrodynamic models of tidal variations and currents [1,8,13-17].

One of the coastal activities that are carried out on the gulf water is the desalination activities where fresh seawater extraction and brine disposal from/to the sea is performed. As the scarcity of water in the region is increasing more pressure on desalination of sea water activities is foreseen. This is a fact in most of the region however the main issue in the Gulf of Aqaba is its vulnerability to pollution.

In this paper, numerical investigation on the impact of the implementation of a desalination activity located on the northern end of the GOA is performed. The investigation evaluates the impact of the abstraction/disposal of sea water on the GOA environment. The studied scenarios are basically 1) only abstraction of large quantities of sea water, and 2) abstraction of large quantities of sea water and disposal of desalinated brine to the GOA. It is likely that withdrawal of large quantities of water may induce negative impact on the marine environment [18].

This study aims at developing a basin-wide 3D hydrodynamic modeling framework for assessing the impacts of different abstraction/disposal scenarios on the hydrodynamic circulation and marine environment of GOA. The model was constructed using Delft-3D model package. The developed model, at the present stage, is preliminary where the results provide qualitative assessment on the potential impacts on the water circulation. Accordingly, this study is considered a pace ahead for a better model development and validation in the future studies.

2. Data Collection

The first step in developing the 3D hydrodynamic model for the Gulf is to define and collect the basic data required for the model development. These data include the geography and bathymetric data of the Gulf, the basic inflows and outflows from the Gulf and the meteorological parameters specially the ones affecting the hydrodynamic analysis.

It is worth to mention that limited data were available during the development of the model and to note also that measurements for calibration were very limited.

The data that were made available during the model development include the following:

• The model bathymetry was based on the acquired global bathymetry dataset for the world ocean “GEBCO_08” [19] available at http://www.gebco.net. GEBCO-08 is a global 30 arc-second horizontal resolution. Data for the GOA were extracted from the global dataset and converted into the appropriate file format for establishing the numerical modeling.

• Land boundary were extracted from the GEBCO-08 dataset assuming that grid points with elevation greater than zero are to be considered as land points.

• The inflow from natural streams to the sea is very limited and accordingly was not considered in the study.

3. Model Development

The large-scale hydrodynamics and the associated mass transport in the deep GOA are clearly three-dimensional phenomena. Strong horizontal as well as vertical gradients in water temperature are observed, [5]. The spatial variation resulted from, among other factors, elongated shape, wind driven flow, and upwelling/down-welling as controlled by thermal stratification, [16]. This assessment advocated the development of coherent three-dimensional model. The 3D modeling framework for the GOA was established using the hydrodynamic Delft3D-FLOW model. This model is embedded in the Delft-3D user friendly interface.

3.1. Model Setup

A detailed curvilinear 3-D grid was developed. The 3-D grid was selected to represent the thermal stratification and to capture for the natural thermocline circulation in the gulf. The resulting 3-D computational grid for GOA is shown in Figure 2.

The horizontal grid contains 209 cells along the gulf centerline and 21 in the transversal direction and is expressed in the spherical coordinate system. As stated earlier, the water depth at each grid point was made using the global bathymetry dataset for the world ocean “GEBCO_08” with 30 arc-second horizontal resolutions (about 1 km).

As for vertical resolution, 30 layers were applied. The vertical layers are defined in a so called sigma co-ordinate system. In this system, each layer has a thickness that is a constant fraction of the local water depth. Because of the complex dynamics in the upper part of the water column characterized by temperature gradients and stratification, thin layers were chosen at the water surface

Figure 2. The curvilinear grid and schematized bathymetry for GOA: (a) in the hydrodynamic model via DELFT3DFLOW; (b) Computational grid and bathymetry in the northern end of the gulf near the city of Aqaba and (c) The southern-open end of the gulf at the straits of Tiran.

and thick layers near the bottom. The top layer fraction was chosen as 1% of the water depth; so with a maximum depth of 1700 m the maximum top layer thickness is 17 m and the maximum bottom layers thickness is about 85 m.

3.2. Initial and Boundary Conditions

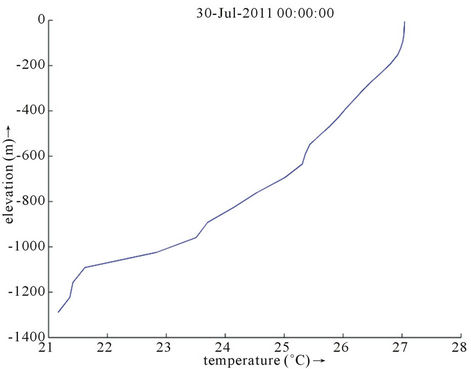

As any other hydrodynamic model, The Delft3D-Flow model requires initial and boundary conditions as well as meteorological and heat forcing. The hydrographic data for initializing the model were applied uniformly over the computational grid (uniform water temperature of about 27˚C and uniform salinity of 40.6 × 103 ppm. A water level boundary driven with astronomical constituents is applied at the southern boundary of the model (Figure 3). Four astronomic tidal constituents (O1, K1, S2, and M2)—obtained from the Admiralty Tide Tables Volume 3 prepared by UK Hydrographic Office in 2007 [20]—were employed to estimate the water level at the southern open boundary. The water level varies from about 0.17 m to 0.87 with 0.70 m tidal range. Temperature and salinity profiles, shown in Figure 4, were specified at the southern open boundary. These profiles were extracted from a continuous record observed at a hydrographic station located 10 km south of the north end of the GOA in accordance with reference [18]. Along the east, west, and north coasts of the gulf, a condition of normal flow was assumed, i.e. u = 0 on the east and west coasts and v = 0 on the north coast. The heat flux computations were turned off in the current set of experiments due to the unavailability of required meteorological forcing data. In case of GOA, no rivers and related data are required in the gulf.

Figure 3. Water level variation based on astronomic tidal constituents applied uniformly at the model southern boundary.

Figure 4. Vertical temperature and salinity profiles applied at the model southern boundary. The profiles were observed in July 2005 at a station located 10 km south of the north end of the GOA (RSS, 2010).

4. Development of Simulation Scenarios

Five numerical simulations were performed; the first experiment simulates the present condition as a baseline for comparing the impact of the proposed intake/outfalls. The second and third experiments simulate hypothetical abstraction/disposal volumes for an intake only located at 250 m off the northern coast of the Gulf (2nd experiment) and intake at about 500 m off and an outfall at about 1500 m off the eastern coast of the Gulf close to Jordan-Saudi Arabia boarder (3rd experiment). The fourth and fifth experiments simulate another proposals for abstraction/disposal volumes for an intake at about 500 m off the northern coast of the Gulf and an outfall at about 1000 m off the eastern coast of the Gulf (4th experiment), and an intake at about 500 m off the northern coast of the Gulf and desalination brine mixed with the cooling water and disposed via an open channel located at the eastern coast of the Gulf (5th experiment). Table 1 summarizes different characteristics of the performed numerical simulations. Locations of the intake/ outfall for each experiment are illustrated in Figure 8.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results of the Hydrodynamic Computations for Present Condition

A one-month simulation time was specified for the summer season during the month of July for all scenarios. The model reproduced the main characteristics of the gulf circulation and hydrography as compared to the previous studies and the available data. This could be demonstrated as follows:

The surface flow field is rather complex (Figure 5), and is composed of a chain of eddies/circulations along the main axes of the gulf as reported in previous modeling studies carried by [1,2,13,21] and in current measurements along the basin by [13]. The general circulation consists of relatively warm and fresh water that enters from the south through the Straits of Tiran as a surface layer, and flows northward, whereas the cold and saline water of the Gulf exits as the bottom layer of the exchange flux.

The model reproduced the thermal stratification in summer (July) as revealed from the typical vertical temperature profile, Figure 6. A temperature gradient of about 6˚C exists between warm surface layer and the relatively cool deep water. Conforming to the observed temperature profile shown in Figure 4, with a relatively milder vertical temperature gradient at the surface, the

Figure 5. A snapshot of the surface flow field in the GOA that composes of a chain of eddies along the Gulf. The color scale represents the current velocity magnitude.

Table 1. Attributes of the conducted GOA numerical experiments.

computed surface temperature does not exceed 28˚C and the deepwater temperature does not go below 21˚C.

The distribution of the water temperature along the Gulf centerline (Figure 7) shows a positive temperature gradient in the south-north direction that result in warmer temperatures near northern end of the Gulf and proving suitable conditions of deepwater formation at the northern tip of the gulf.

5.2. Effect of Abstraction and Disposal Scenarios

To investigate the effect of abstraction/disposal alternatives on the GOA conditions, three reference X-SECTIONS were selected across the Gulf (refer to Figure 8 for location), namely X-SECTION50 near the middle of the Gulf, X-SECTION100 at the northern 1/3 of the Gulf, and X-SECTION200 at the northern end of the Gulf. Maximum flow velocity magnitudes from the present condition situation were compared to the corresponding values from the abstraction/disposal experiments. In addition to the absolute maximum velocity magnitude, the

Figure 6. Typical computed temperature profile at a point near the south of the GOA in summer (maximum temperature at surface reaches about 28˚C and minimum temperature do not go beyond 21˚C).

residual maximum velocity magnitude for each alternative was computed and presented noting that the residual velocity magnitude is calculated as the maximum velocity for the alternative minus the maximum velocity in the present condition.

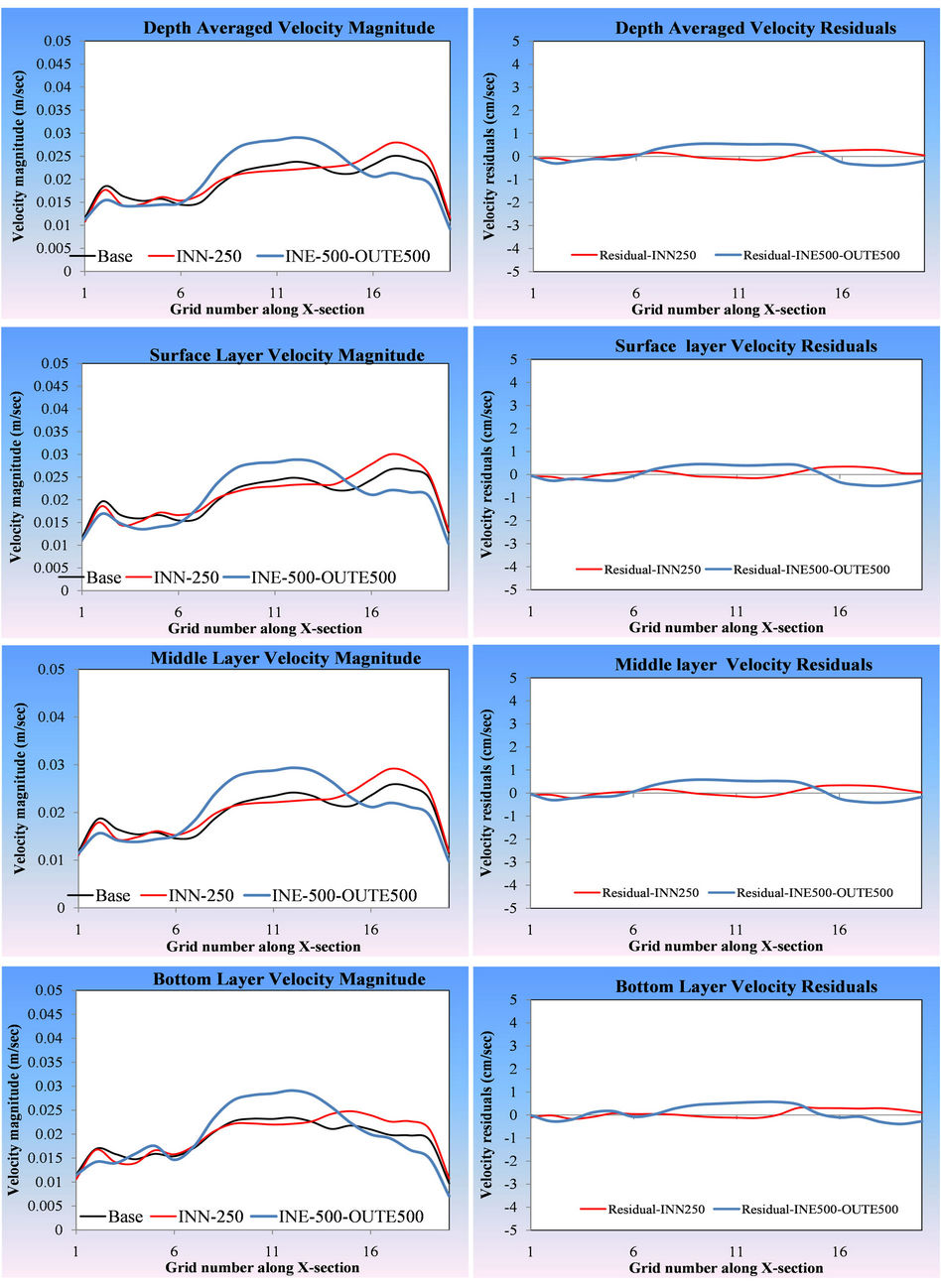

Figure 9 shows the maximum and residual maximum

Figure 7. Computed water temperature profile along GOA centerline.

Figure 8. (a) Location of reference X-SECTIONS 50, 100 and 200 at which maximum and residual velocity magnitudes are compared, and (b) shows the location of intakes/ outfalls of the model experiments.

Figure 9. Maximum (left) and residual (right) current magnitude across X-SEC 50 due to ultimate phase abstraction and disposal scenarios (INN250 and INE500-OUTE1500).

Figure 10. Maximum (left) and residual (right) current magnitude across X-SEC 100 due to ultimate phase abstraction and disposal scenarios (INN250 and INE500-OUTE500).

Figure 11. Maximum (left) and residual (right) current magnitude across X-SEC 200 due to ultimate phase abstraction and disposal scenarios (INN250 and INE500-OUTE500).

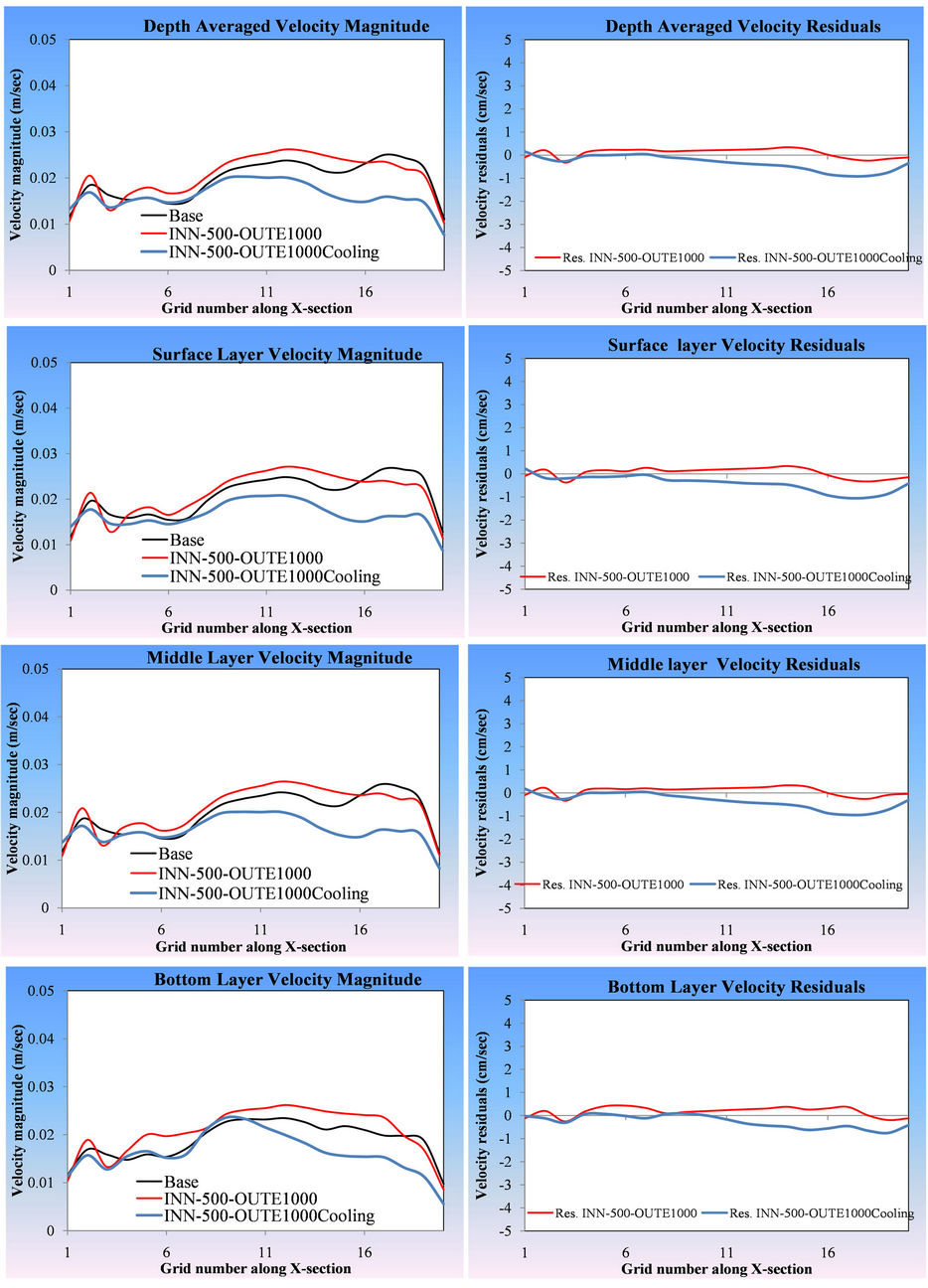

Figure 12. Maximum (left) and residual (right) current magnitude across X-SEC 50 due to first phase of abstraction and disposal scenarios (INN500OUTE1000 and INN500OUTECooling).

Figure 13. Maximum (left) and residual (right) current magnitude across X-SEC 100 due to first phase of abstraction and disposal scenarios (INN500OUTE1000 and INN500OUTECooling).

Figure 14. Maximum (left) and residual (right) current magnitude across X-SEC 200 due to first phase of abstraction and disposal scenarios (INN500OUTE1000 and INN500OUTECooling).

current magnitude at X-SECTION 50. The depth averaged current magnitude shows larger currents at the Gulf sides (0.15 m/sec) compared to the central part (0.05 m/sec). The bottom layer current magnitude are apparently higher than surface and middle layer currents, this could be explained by the density current flow from the northern head of the gulf toward the south. The abstraction and disposal scenarios shows non-uniform residual currents across the X-SECTION with a maximum value of 7 cm/sec. Model results show higher current residual near the eastern side of the Gulf compared to the western side.

At X-SECTION 100, the residual maximum current magnitude of the INN250 scenario is generally higher than the corresponding residual current of the INE500- OUT500 (Figure 10). In the two scenarios, current residuals are in the order of ±5 cm/sec. Toward the north of the Gulf at X-SECTION 200, near stagnant conditions prevails with maximum current magnitudes of 3cm/sec. the abstraction disposal scenarios shows negligible effect on the current values (Figure 11).

Figures 12-14 are the maximum and residual current magnitude at the same reference X-SECTIONS for scenarios INN500-OUTE1000 and INN500-OUTE1000 Cooling for the other proposal of abstraction and disposal with reduced discharges. The residual current magnitudes at X-SEC 50 and 100 are in the order of ±5 cm/sec. As a result of the abstraction/disposal, surface and middle layer current magnitudes at the eastern side of the Gulf show relative increase compared to the western side. Toward the northern head of the Gulf, near stagnant conditions prevails with negligible effect of the abstraction/disposal on velocity magnitudes (Figure 14).

6. Conclusions and Recommendation

The public domain version of the Delft-3D modeling package was employed to prepare a preliminary hydrodynamic model of the GOA to estimate the potential effects of the different abstraction/disposal alternatives of desalination plants on the current circulation and marine environment in the Gulf. The following concluding remarks are based on the results of this study. Although the model is not quantitatively calibrated it is qualitatively verified since the results of the present condition reveal that primary eddies are formed along the centerline of the Gulf which are in line with former studies made by others.

The model reproduced the thermal stratification in summer (July) as revealed from the typical vertical temperature profile, Figure 6. A temperature gradient of about 6˚C exists between the warm surface layer and the relatively cool deep water. Conforming to the observed temperature profile shown in Figure 4, the computed surface temperature does not exceed 28˚C and the deep water temperature does not go below 21˚C.The distribution of the computed water temperature along the Gulf centerline shows a positive temperature gradient in the south-north direction that result in warmer temperatures near northern end of the Gulf and proving suitable conditions of deepwater formation at the northern tip of the gulf.

Preliminary results of the abstraction/disposal scenarios from the model show that larger current speeds are observed at the Gulf sides compared to the central part.The northern end of the Gulf has near stagnant current condition with maximum current magnitudes of 2 - 3 cm/sec. All abstraction/disposal alternatives had negligible effect on current residuals at this location. A current velocity close to the seabed was found to be larger than that at the water surface. This reveals the existence of the density current due to the brine water disposed of the proposed desalination plants.

The model results need to be closely analyzed by marine ecologist to assess the potential impacts on the marine environment in the GOA;

The GOA hydrodynamic model is still in its early phases of development, the model requires extra effort for model enhancements. The current version of the model did not consider the surface heat fluxes (air temperature, wind speed, solar radiation, and relative humidity) due to lack in meteorological observations. Since heat flux is expected to have a crucial role in thermocline circulation and temperature-salinity variation, it must be considered in any further refinements of the model.

7. Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dar Al-Handasah, “Shair and partners,” Resource & Environment Department, for their unlimited encouragement and support.

REFERENCES

- T. Berman, N. Paldor and S. Brenner, “Simulation of Wind-Driven Circulation in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba),” Journal of Marine Systems, Vol. 26, No. 3-4, 2000, pp. 349-365. HUdoi:10.1016/S0924-7963(00)00045-2U

- E. Biton and H. Gildor, “The General Circulation of the Gulf Aqaba (Gulf of Eilat) Revisited: The Interplay between the Exchange Flow through the Straits of Tiran and Surface Fluxes,” Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 116, No. C08020, 2011, pp. 1-15.

- G. Assaf and J. Kessler, “Climate and Energy Exchange in Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat),” Monthly Weather Review, Vol. 104, 1976, pp. 381-385. HUdoi:10.1175/1520-0493(1976)104<0381:CAEEIT>2.0.CO;2U

- J. Klinker, Z. Reiss, C. Kropach, I. Levanon, H. Harpaz, E. Halicz and G. Assaf, “Observations on the Circulation Pattern in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba), Red Sea,” Israel Journal of Earth Sciences, Vol. 25, 1976, pp. 85-103.

- N. Paldor and D. Anati, “Seasonal Variations of Temperature and Salinity in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba),” Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers, Vol. 26, No. 6, 1979, pp. 661-672. HUdoi:10.1016/0198-0149(79)90039-6U

- Z. Reiss and L. Hottinger, “The Gulf of Aqaba, Ecological Micropaleontology, Ecological Studies,” Vol. 50, Springer, Berlin, 1984, 354 p.

- Wolf-Vecht, A., N. Paldor and S. Brenner, “Hydrographic Indications of Advection/Convection Effects in the Gulf of Eilat,” Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers, Vol. 39, No. 7-8, 1992, pp. 1393-1401. HUdoi:10.1016/0198-0149(92)90075-5U

- J. Silverman and H. Gildor, “The Residence Time of an Active versus a Passive Tracer in the Gulf of Aqaba: A Box Model Approach,” Journal of Marine Systems, Vol. 71, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 159-170. HUdoi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.06.007U

- E. Biton, J. Silverman and H. Gildor, “Observation and Modeling of Pulsating Density Current,” Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 35, No. L14603, 2008, 5 p.

- M. Ben-Sasson, M. S. Brenner, and N. Paldor, “Estimating Air-Sea Heat Fluxes in Semienclosed Basins: The Case of the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba),” Journal of Physical Oceanography, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2009, 185-202.

- A. Hecht and D. Anati, “A Description of the Straits of Tiran in Winter 1978,” Israel Journal of Earth Sciences, Vol. 32, 1983, pp. 149-164.

- S. Murray, A. Hecht and A. Babcock, “On the Mean Flow in the Tiran Strait in Winter,” Journal of Marine Research, Vol. 42, No. 2, 1984, pp. 265-284. HUdoi:10.1357/002224084788502738U

- R. S. Manasrah, M. Badran, H. U. Lass and W. Fennel, “Circulation and Winter Deep-Water Formation in the Northern Red Sea,” Oceanologia, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2004, pp. 5-23.

- S. G. Monismith and A. Genin, “Tides and Sea Level in the Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat),” Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 109, No. C04015, 2004, pp. 1-6.

- E. Biton, E., H. Gildor, G. Trommer, M. Siccha, M. Kucera, M. T. J. Van der Meer and S. Schouten, “Sensitivity of Red Sea Circulation to Monsoonal Variability during the Holocene: A Modeling and Sediment Record Study,” Paleoceanography, Vol. 25, No. PA4209, 2010, 16 p. HUdoi:10.1029/2009PA001876U

- R. Manasrah, H. Uli Lass and W. Fennel, “Circulation in the Gulf of Aqaba (Red Sea) during Winter-Spring,” Journal of Oceanography, Vol. 62, No. 2, 2006, pp. 219- 225. HUdoi:10.1007/s10872-006-0046-6U

- H. Gildor, E. Fredj and A. Kostinski, “The Gulf of Eilat/Aqaba: A Natural Driven Cavity?” Geophysical & Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics, Vol. 104, No. 4, 2010, pp. 301-308.

- RSS, “Red Sea Study, Best Available Data Report: Additional Studies of the Red Sea Water Conveyance Study Program Funded by the World Bank,” 2010.

- J. J. Becker, D. T. Sandwell, W. H. F. Smith, J. Braud, B. Binder, et al., “Global Bathymetry and Elevation Data at 30 Arc Seconds Resolution: SRTM30_PLUS,” Marine Geodesy, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2009, pp. 355-371.

- UK Hydrographic Office, “Admiralty Tide Tables,” Vol. 3, 2007.

- S. Brenner and N. Paldor, “High Resolution Simulation with Princeton Ocean Model,” Technical Report, IET Project No. 6, 2004.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.