Advances in Aging Research

Vol.3 No.1(2014), Article ID:42937,11 pages DOI:10.4236/aar.2014.31009

The effects of a patient-centred rehabilitation model of care targeting older adults with cognitive impairment on healthcare practitioners

![]()

1Department of Kinesiology, University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada

2Department of Kinesiology and Health Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

3Department of Research, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada

4Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; *Corresponding Author: kathy.mcgilton@uhn.ca

Copyright © 2014 Paula M. van Wyk et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Paula M. van Wyk et al. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received 21 November 2013; revised 21 December 2013; accepted 28 December 2013

KEYWORDSHip Fracture; Cognitive Impairment; Rehabilitation; Patient-Centred; Attitudes; Job Satisfaction; Work Stress

ABSTRACT

Until recently, older adults with a cognitive impairment (CI) who experienced a hip fracture were filtered from being admitted into active rehabilitation units. The increased complexity of care required for older adults with a CI may negatively influence the attitudes and job satisfaction of healthcare practitioners working with this population. The current study is a part of a larger intervention study allowing patients with CI following a hip fracture to have access to rehabilitation care and implementing a patient-centred model to facilitate caring for this new population. This new model required a substantial change in the skillset and knowledge of healthcare practitioners. The focus of this study was to explore the impact on the healthcare practitioners of adopting this new model for providing care to older adults with a CI following a hip fracture. The attitudes, dementia knowledge, job satisfaction, and work stress of healthcare practitioners were the focus of evaluation. Key study findings showed that stress due to relationships with coworkers, workloads and scheduling, and the physical design and conditions at work were moderated post-intervention. Staff responses also improved for job satisfaction, biomedical knowledge of dementia, and degree of hopefulness about dementia. Although we cannot state conclusively that the our model was solely responsible for all the staff improvements obser- ved post-intervention, our findings provide further support to the argument that patients with CI should be allowed to have access to rehabilitation care. Rehabilitation units need to provide education that utilizes a person-centred approach accepting of patients with CI, and focuses on areas that can bolster staff’s positive, dementiasensitive attitudes. Ultimately, the aim is to create a culture that provides the highest standard of care for all patients, reduces work-related stress, increases job satisfaction, and leads to the highest quality of life for patients during and after rehabilitation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Demand for specialized geriatric care has been rising as a result of the demographic shift towards an aging population and the increased complex care needs of older adults. During hospitalization, older adults have an increased likelihood of developing complications [1]. Dedicated geriatric Acute Care of Elders (ACE) units were developed to create specialized environments focused on keeping older adult patients active and independent while hospitalized [2,3]. The formation of ACE units necessitated a change in staff practice to incorporate a team approach to providing multidisciplinary gerontological care

[2,3]. A meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of ACE units found that, in comparison to usual care, older adults admitted to these dedicated geriatric units had a reduced rate of falls, less functional decline, shorter length of stay, and fewer incidences of delirium and discharge to nursing homes [3]. These positive findings however, were applicable only to medical, surgical, and medical-surgical units [3]. Although growing in popularity, ACE units have not been implemented in all hospital settings due to the associated start-up costs and the scarcity of geriatricians who play an integral role in functional and successful ACE units [1,2]. To help meet the need in other settings, the Patient-Centred Rehabilitation Model with specific components for patients with Cognitive Impairment (PCRM-CI) was developed for musculoskeletal rehabilitation units and for existing staff currently on the unit, a care setting and team that does not typically include a geriatrician. Similar to ACE units, the PCRM-CI emphasizes creating a supportive environment, utilizes a patientand family-oriented care focus, and facilitates the education and support of healthcare practitioners to provide more specialized geriatric complex care.

The PCRM-CI was specifically designed for older adults with cognitive impairment (CI), including those with a dementia or delirium, following a hip fracture. More than 35,000 Canadians suffer a hip fracture annually, an event with major repercussions for older adults, their family and caregivers, healthcare professionals, and the healthcare system [4-6]. Individuals with Alzheimer’s or a related dementia have a higher incidence of hip fractures than cognitively intact older adults [4,7]. Notably, the incidence of delirium following a hip fracture is also common among older adults who have experienced a hip fracture (35% - 62%) [8-13]. Patients with CI are often deemed unsuitable candidates for rehabilitation and excluded from active rehabilitation programs [6,14,15]. Access is limited to the few specialized geriatric rehabilitation beds in the Canadian healthcare system open to persons with CI. The exclusion of persons with CI from active rehabilitation programs further disables individuals suffering a debilitating injury, inevitably delaying or preventing a return to independence and enhanced physical and cognitive functioning.

The PCRM-CI consists of five components: 1) rehabilitation management; 2) dementia management; 3) delirium management; 4) staff education and support; and 5) individualized family support and education. In the model’s implementation reported on in this study, the rehabilitation management component provided access to care for all older adults following a hip fracture regardless of cognitive reserve, ensured intensive interdisciplinary daily rehabilitation, and involved the patient and family in setting person-centred goals and discharge plans [16]. The dementia and delirium management components involved cognitive assessments of all patients within the first 3 days of admission and teaching healthcare practitioners a person-centred care approach. To increase staff’s knowledge about the needs of patients with CI, a gerontology expert (a Master’s-prepared advanced practice nurse [APN]) facilitated on-site learning through a workshop, in-services and just-in-time sessions for staff. During the one-year intervention, the APN provided bedside mentoring and support plus education as required based on the needs of staff. The families of patients were also provided with education and support to help navigate the patient’s rehabilitation pathway, both in-hospital and after discharge home [16]. Together, these combined elements formed the basis of a patientand family-oriented model of care for older adults with CI following a hip fracture that included vital geriatric and complex care expertise. Preliminary evidence of the model’s efficacy has recently been demonstrated, which included testing patients’ functional gains and rate of return to their previous living situation post-discharge from inpatient rehabilitation [17].

This paper will focus on staff attitudes towards working with older adults with CI and staff perceptions of workplace implementation of the PCRM-CI. Adopting this new model of care required a substantial change in the skillset and knowledge of healthcare practitioners, mainly nursing staff and allied health professionals such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and social workers, who were now asked to care for a new group of patients (i.e., those with CI). It has been shown that healthcare practitioners, primarily nursing staff but also other allied health professionals, lacked the necessary skills and knowledge about cognitive and behavioural strategies to care for older adults with CI transferred to inpatient rehabilitation settings following a hip fracture [18,19]. From the perspective of healthcare practitioners, disturbances in cognition and rehabilitation participation were common among patients with CI and were associated with poorer functional outcomes [20,21]. Patients’ agitation, anxiety, or irritability influenced the efforts of healthcare practitioners in rehabilitating their clients [19]. Furthermore, healthcare practitioners were not aware of strategies to manage these symptoms [19].

Most of the research to date examining attitudes regarding working with older persons has focused on nursing staff and demonstrated that the attitudes nurses have towards their patient population both significantly and directly impact the care that they provide [22-24]. It has been reported that many nurses, both students and practicing nurses, have negative attitudes towards providing care to and working with older adults [23,25]. Some studies, however, have suggested that attitudes may be more positive among staff, including nurses, working in rehabilitation settings [23,26-28]. Furthermore, it was also found that when student nurses had positive attitudes towards older adults, they also had a greater tolerance of older adult patients, expressed greater job satisfaction working with this population, and were personally less worried about growing old [24]. With the demographic shift towards an increase in the older adult population, negative attitudes towards working with and providing care to older adults may relate to poor quality of care for older adults and decreased job satisfaction among nurses. Typically, older adult patients who are confused as a result of a dementia or delirium receive less interaction from healthcare practitioners than patients who are cognitively intact [29,30]. Furthermore, it has been argued that relying on a biomedical model of care, with its specific focus on the medical and physiological complications of disease, without considering the patient as a person, is not adequate for providing sufficient training and practice to meet the care needs of older adults with CI [31]. In order to care for this patient population, healthcare practitioners need to be knowledgeable about dementia and delirium, be flexible with their duties to accommodate patients, and be willing to put forth added effort to provide more patient-centred care [31].

Interventions for staff may be one way to influence attitudes. In an extensive literature review, Courtney et al. found that nurses’ positive attitudes towards older adults increased following an educational intervention that allowed for more patient power in decision-making than a strictly biomedical model [23]. Recently, McCabe et al. conducted a review of studies that focused on the effectiveness of staff training programs in long-term care aimed at dealing with behavioural problems among older people with dementia [32]. The majority of these programs were designed to increase the skillset and knowledge of staff regarding the behavioural management of their patients [33-35]. Staff outcomes following training included 1) improved knowledge of behaviour management [34]; 2) improved knowledge of dementia [33]; and 3) increased job satisfaction and reduced stress [36,37].

This paper is a report of a study that explored the impact on healthcare practitioners of adopting the PCRMCI to care for older adults with CI following a hip fracture. It was expected that as the PCRM-CI was implemented and as staff were introduced to older adults with multiple comorbidities, including dementia and delirium, staff would experience a degree of change in attitudes, knowledge, and level of stress. This study is a component of a much larger intervention study that focused on patient outcomes of functional mobility and cognitive impairment following a hip fracture associated with the implementation of the PCRM-CI model on rehabilitation units in Central-East Ontario.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and Setting

Healthcare practitioners (i.e., nursing staff and other allied health professionals such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and social workers) working on the rehabilitation units in two different hospitals were invited to participate. Implementation of the PCRM-CI into the geographical region where these two hospitals were located was timely, as this area has a high concentration of seniors and the highest number of elderly people with dementia in all of Ontario, Canada. Site 1 was a 40-bed musculoskeletal rehabilitation unit; Site 2 was a 20-bed musculoskeletal rehabilitation unit. The implementation of this new model of care at the two sites was part of a larger intervention study, of which only the staff outcome data will be discussed in this paper. At each site, one usual care cohort, followed by one intervention cohort, were recruited and followed for approximately one year. All associated organizations provided ethics approval for this project (TRI REB#09-016).

2.2. Data Collection

Participating healthcare practitioners completed a questionnaire examining their attitudes, work-related stress, job satisfaction, and knowledge of working with patients with CI at two time points. The first, prior to implementation of the PCRM-CI, occurred when staff attended an educational workshop facilitated by the Principal Investigator (KM) and the APN. Approximately one year later, the healthcare practitioners completed the questionnaire a second time. All questionnaires were returned anonymously to a designated location and collected by a research assistant. Written informed consent was an included component of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consisted of five sections: demographics, including personal and professional characteristics; the Satisfaction Working with Patients with Dementia measure; the Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire (ADQ); the Dementia Quiz; and a modified Work Stress Inventory (WSI) measure. For personal and professional characteristics, respondents were asked to disclose their age, sex, education (certificate, diploma, Baccalaureate, Master’s), experience, job category, and length of time working on the unit.

The Satisfaction Working with Patients with Dementia measure included 21 items assessing satisfaction, each scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 84. Higher scores indicated more satisfaction. The scale’s overall reliability (µ = 0.87) and validity have been demonstrated [38]. The ADQ, which was used to assess healthcare practitioners’ attitudes [39], consisted of 19 statements about people with dementia and their care, for which degrees of agreement or disagreement were sought on a 5-point Likert scale. Two subscales indicated the healthcare practitioners’ degree of hopefulness about dementia and the extent to which the individual supported a personcentred approach [39]. Higher scores indicated more positive attitudes. The subscales have been shown to have good reliability (µ = 0.65 for hope and µ = 0.75 for person-centered; µ = 0.75 for overall) and have been validated against direct observation of the quality of staff care interactions with patients [38,40].

The Dementia Quiz was used to measure the knowledge that the healthcare practitioners had about dementia [41]. It consisted of 16 items with one subscale focused on biomedical knowledge and a second on coping strategies that staff can use when patients exhibit behavioral or cognitive symptoms related to their dementia. Higher scores on the scale indicated more knowledge about dementia. The subscales have moderate reliability (µ = 0.63 for knowledge and µ = 0.57 for coping) and have demonstrated predictive validity for staff experienced with caring for persons with dementia [41].

The modified WSI measure was derived by averaging the frequency of 45 workplace stressors, each scored 1 (never—not at all) to 5 (often—very well). Higher scores indicated more stress. Subscales were grouped into three domains: task stressors, relationship stressors, and system stressors. The WSI subscales were stable over time for the indices [42].The scale’s overall reliability (µ = 0.93) and validity have been demonstrated [38].

2.3. Data Analysis

Frequencies were calculated for each of the healthcare practitioners’ categorical demographic and work experience characteristics. Means and standard deviations were calculated for each continuously distributed variable. Univariate comparisons of preand post-intervention responses were also calculated for each scale and their Cronbach’s alpha.

Multi-level mixed-effects regression analysis was used to evaluate whether responses differed post-intervention, while accounting for clustered sampling of healthcare practitioners within facilities, repeated measures within healthcare practitioners, and healthcare practitioner-level predictors such as age, education, and work experience. Facilities and healthcare practitioners were considered random effects; healthcare practitioner-level predictors were considered fixed effects. Whether the influence of the intervention remained constant with years of work experience was evaluated using the interaction between years of work and the intervention. Analyses were performed using STATA (Version 11.2).

3. RESULTS

Before you begin to format your paper, first write and save the content as a separate text file. Keep your text and graphic files separate until after the text has been formatted and styled. Do not use hard tabs, and limit use of hard returns to only one return at the end of a paragraph. Do not add any kind of pagination anywhere in the paper. Do not number text heads—the template will do that for you.

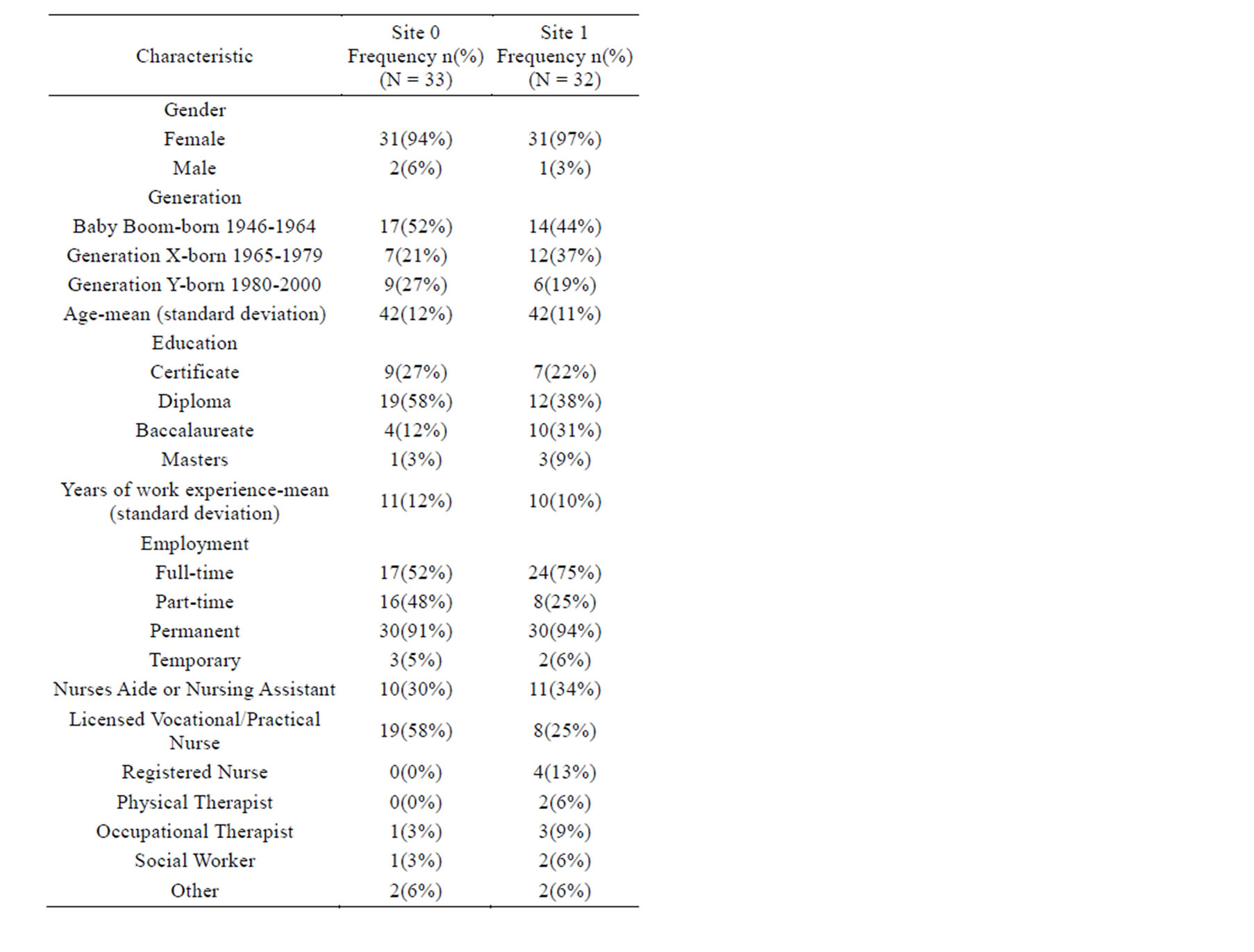

The sample of healthcare practitioners (N = 65) was predominately female (95%), ranged in age from 22 years to 62 years with a lower quartile of 32 and an upper quartile of 51, and averaged 11 years of work experience (Table 1). Most were employed full-time either as nurse’s aides or assistants or as licensed vocational or practical nurses (Table 1).

Table 2 shows scores from the Satisfaction Working with Patients with Dementia measure. Overall satisfaction scores were skewed towards the positive both preand post-intervention (53.9 and 57.5 out of a possible 84, respectively). In general, all satisfaction scores were higher post-intervention. Satisfaction with patient contact scores was higher than the mean satisfaction scores for the other subscales, whereas satisfaction with the environment had a lower mean satisfaction score than the other subscales.

Table 1. Health care professional characteristics by site.

Table 2. Means & standard deviations of response scales preand post-intervention.

Scores on the ADQ were also found to be skewed towards the positive in both the preand post-intervention analyses (73.5 and 72.6 out of a possible 95, respectively). Among the two subscales, positive attitudes were more evident among personhood than hopefulness (Table 2). The overall dementia knowledge scores from the Dementia Quiz (Table 2) were likewise skewed towards the positive for both the preand post-intervention analyses (11.3 and 11.6 out of a possible 16, respectively). The dementia knowledge score appeared to be higher postintervention when compared to pre-intervention. Scores for both the biomedical and coping subscales also appeared to increase slightly from pre-intervention to postintervention.

A lower score for the WSI was viewed as positive as it indicated that stress was lower. Overall, work stress scores were lower post-intervention (Table 2). Task stress was the domain with the highest work stress, both preand post-intervention (3.01 and 2.84 out of a possible 5, respectively). The subscale with the highest work stress scores was caring for patients. Relationship stress was the domain with the lowest work stress, both preand postintervention (2.10 and 1.94 out of a possible 5, respectively). The subscale with the lowest work stress scores pre-intervention was relationships with coworkers (2.10 out of a possible 5), and post-intervention was relationships with supervisors and doctors (1.88 out of a possible 5).

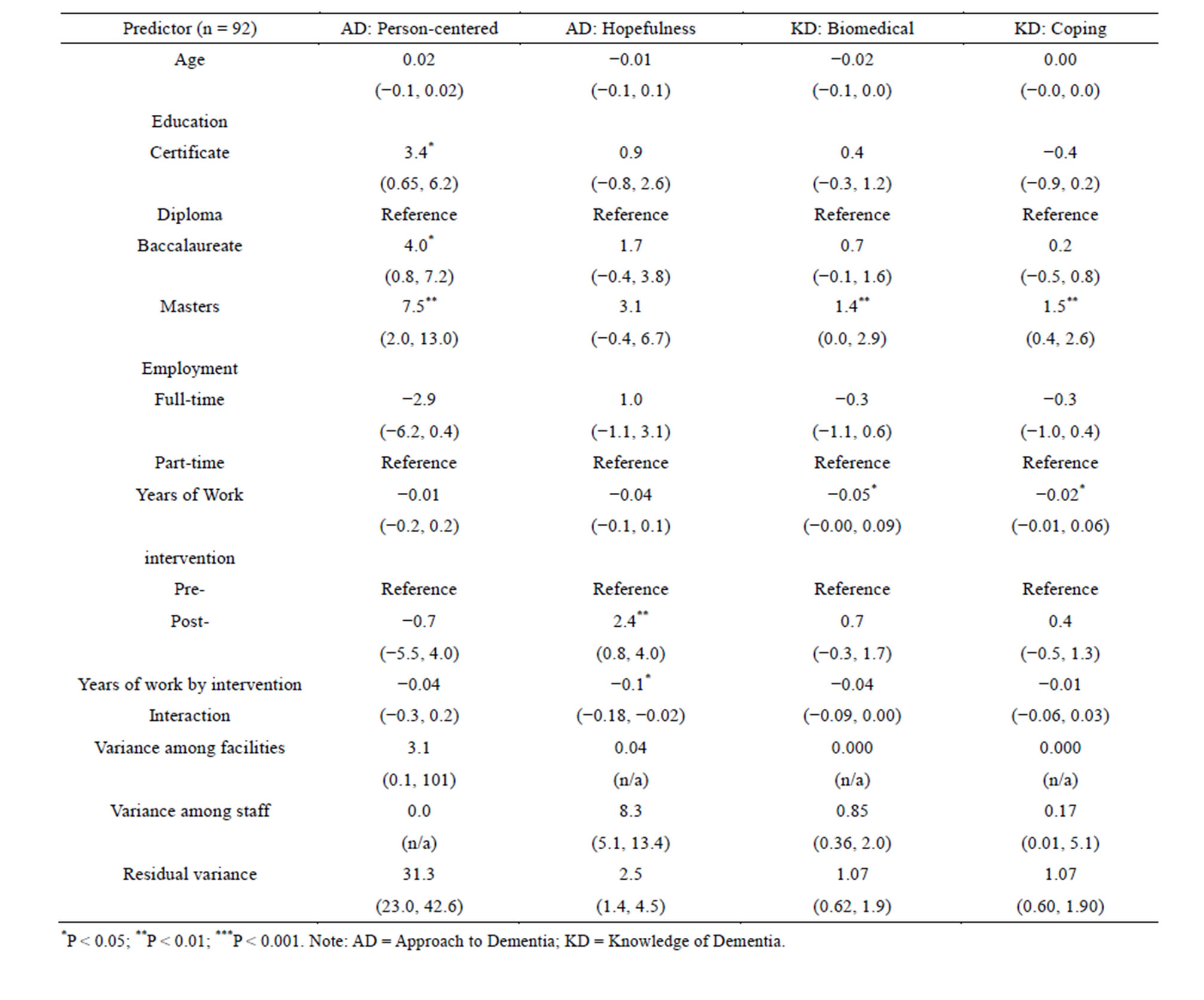

Table 3 presents the multi-level, mixed effects linear regression analyses for each of the outcomes. Satisfaction working with patients with dementia was 7.2 units greater post-intervention (p < 0.01). Scores for the care organization, satisfaction of own expectations, and satisfaction with the expectations of others’ subscales each contributed to this difference. While in each case, the positive influence of the intervention weakened among staff with more years of work experience, this attenuation was clear for only the satisfaction of own expectations subscale (p < 0.05). Staff with more work experience were more satisfied with respect to care organization and with their work environment. Staff that employed full-time were less satisfied with respect to care organization, but more satisfied with the expectations of others. Furthermore, staff with graduate-level education (e.g., Master’s prepared) were less satisfied with the expectations of others’ in comparison to those with less education.

Work stress was significantly lower post-intervention for overall system stress, workload and scheduling, physical design conditions at work, overall relationship stress, and relationships with coworkers (Table 3). Scores for other components of the WSI appeared to be lower postintervention, but these results could have been caused by chance. Full-time staff consistently scored higher on the WSI components in comparison to their part-time colleagues, with the exception of stress associated with caring for patients, physical design and conditions at work, and relationships with supervisors, in which stress was greater but not statistically significant. Among staff with different levels of education, those with certificate education indicated significantly less stress than their colleagues who had earned a diploma.

Scores for the hopefulness subscale from the ADQ were higher post-intervention, but the degree of hopefulness was attenuated with years of work experience (Table 3). The personhood subscale scores were higher for healthcare practitioners with a certificate education, Baccalaureate degree, and Master’s degree than they were for those with a diploma education. Staff with a Master’s degree also had a greater knowledge of dementia.

4. DISCUSSION

Adopting the PCRM-CI had a number of significant effects on staff’s perceptions of their jobs and on their attitudes towards working with older adults with CI. Key study findings showed that stress due to relationships with coworkers, workloads and scheduling, and the physical design and conditions at work was moderated post-intervention. Staff responses also improved for job satisfaction, biomedical knowledge of dementia, and degree of hopefulness about dementia. Post-intervention improvement generally lessened with years of experience, though the diminishment was statistically significant in only one case. The rate of diminishment, nevertheless, was consistent across response scales such that improvements were greatest for those with the least work experience and were exhausted among those with approximately 25 years of work experience. Healthcare practitioners born between 1980 and 2000 represented the youngest cohort in this study. Respondents in this group, colloquially referred to as members of Generation Y, reported more stress with caring for patients and with the physical design and conditions at work than older healthcare practitioners. Those employed full-time reported greater stress with general job requirements, with caring for patients, with relationships with coworkers, and with workloads and scheduling.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the attitudes, satisfaction, knowledge, and stress associated with providing care in rehabilitation units to patients with CI. Before this new model of care was implemented, patients with a CI traditionally were not accepted into rehabilitation units [21,43,44], and, as Salmonreported, previous arguments suggested that nurses’ attitudes became less positive as their contact with elderly patients increased [30]. Yet the results of the current study demonstrated that as healthcare practitioners in creased their exposure to patients with CI as

Table 3. Multi-level, mixed-effects linear regression analysis of each response scale.

the PCRM-CI was implemented, they also reported improvements in all aspects of dementia care including attitudes towards individuals, job satisfaction, knowledge of the disease, and work-related stress. Our results support Norbergh et al.’s findings that healthcare workers’ attitudes towards older adults with CI were positively skewed, which was attributed to positive attitudes to personhood [45]. Although the PCRM-CI model utilizes a personcentred approach for complex older adults that helps compensate for a patient’s loss of cognitive reserve [16], results from the ADQ in our study did not yield a significant statistical difference in the extent to which staff supported a person-centred approach to dementia care between preand post-intervention. However, positive attitudes among healthcare practitioners were more evident around support for person-centred dementia care than for hopefulness approaches to dementia care.

Holding positive attitudes towards older adults has also been linked to greater job satisfaction [24]. Overall, job satisfaction and work stress working with older adults with CI in a rehabilitation setting improved after the PCRM-CI intervention. The degree of improvement in factors on the WSI measure versus other measures of dementia care and knowledge suggests that positive changes in staff attitudes following PCRM-CI implementation may be more related to improved job satisfaction and reduced work-related stress. The findings of our study corroborated that positive attitudes towards older adults are linked to greater job satisfaction [24] also have important implications for increasing intent to stay among staff. Furthermore, facilitating positive attitudes towards working with older adults may help to alter staff’s misconceptions and increase the number of healthcare practitioners willing to work with older patient populations.

Another potential advantage to using the PCRM-CI model is its person-centred approach. It has previously been argued that a person-centred approach may have a consequence of better preparing staff to care for patients with a CI and thus may also affect increased job satisfaction [38]. This level of care is also crucial for patients with a CI as they may have difficulties communicating their needs. Thus, providing care to this population may be a daunting task to healthcare practitioners. Nonetheless, a person-centred approach has been recognized as the ideal approach for providing care to patients with a CI [46-49]. However, promoting that a person-centred approach is being utilized only implies that the staff have received training and are knowledgeable in how to provide care in this manner. Thus, by implementing a model, such as the PCRM-CI, that incorporates continual education and training to staff as to how best providing personcentred care may improve the job satisfaction and confidence among staff, but also relate to patients receiving more ideal care to meet their needs.

Although staff expressed apprehensions before the intervention about providing rehabilitation care to patients with CI, this study showed that their positive attitudes, satisfaction, and knowledge increased while their stress decreased one year after the model’s implementation. To understand these phenomena further, a future study will involve a qualitative analysis of healthcare practitioners’ and managers’ perceptions regarding implementation of the PCRM-CI model on the rehabilitation units. Furthermore, the APN’s role in our study as a facilitator and educator may have also been a pivotal factor in increasing staff’s positive attitudes, job satisfaction, and knowledge, as well as in decreasing their work-related stress. The APN used a tailored approach that focused on minimizing stress among staff caring for patients with CI and on enhancing staff attitudes and knowledge around working with older adults with CI following a hip fracture. This staff-centred approach may also have contributed to staff’s willingness to provide patient-centred care. This is an area that requires further exploration.

Healthcare practitioners may be reluctant to work with patients with CI because staff lack the specialized experience, education, and training necessary to care effectively for this population. Rehabilitation units need to provide education that utilizes a person-centred approach accepting of patients with CI, and focuses on areas that can bolster staff’s positive, dementia-sensitive attitudes. Although previous studies have found that some nursing staff, particularly in long-term care home settings [50], may have negative attitudes toward older adult patients, staff in our study may have been better able to appreciate the abilities that have remained intact in this population after observing patients return home following rehabilitative care for a hip fracture, regardless of their cognitive reserve. Although we cannot state conclusively that the PCRM-CI was solely responsible for all the staff improvements observed post-intervention, the study’s findings provide further support to the argument that patients with CI should not be refused admittance to rehabilitation units. Ultimately, the aim is to create a culture that provides the highest standard of care for all patients, reduces work-related stress, increases job satisfaction, and leads to the highest quality of life for patients during and after rehabilitation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge CIHR for funding this research. We would also like to thank those involved in the project as a participant, research assistant, or as a member of the research team.

REFERENCES

- Amador, L.F., Reed, D. and Lehman, C.A. (2007) The acute care for elders unit: Taking the rehabilitation model into the hospital setting. Rehabilitation Nursing, 32, 126- 132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00164.x

- Malone, M.L., Vollbrecht, M., Stephenson, J., Burke, L., Pagel, P. and Goodwin, J.S. (2010) Acute care for elders (ACE) tracker and e-geriatrician: Methods to disseminate ACE concepts to hospitals with no geriatricians on staff. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58, 161-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02624.x

- Fox, M.T., Persaud, M., Maimets, I., O’Brien, K., Brooks, D., Tregunno, D. and Schraa, E. (2012) Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60, 2237-2245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12028

- Freter, S. and Koller, K. (2008) Hip fractures and Alzheimer’s disease. The Canadian Review of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 11, 15-20.

- Leslie, W., O’Donnell, S., Jean, S., Lagae, C., Walsh, P., Banej, C., Morin, S., Hanley, D. and Papaioannou, A. (2009) Trends in hip fracture rates in Canada. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 302, 883-889. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1231

- The Bone and Joint Decade (2011) National hip fracture toolkit. http://www.boneandjointcanada.com/?sec_id=310&msid=3

- Seitz, D., Adunuri, N., Gill, S. and Rochon, P. (2011) Prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment among older adults with hip fractures. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 12, 556-564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2010.12.001

- Bitsch, M., Foss, N., Kristensen, B. and Kehlet, H. (2004) Pathogenesis of and management strategies for postoperative delirium after hip fracture: A review. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 75, 378-389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016470410001123

- Gruber-Baldini, A.L., Zimmerman, S., Morrison, R.S., Grattan, L.M., Hebel, J.R., Dolan, M.M., Hawkes, W. and Magaziner, J. (2003) Cognitive impairment in hip fracture patients: Timing of detection and longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 1227- 1236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51406.x

- Magaziner, J., Simonsick, E.M., Kashner, T.M., Hebel, J.R. and Kenzora, J.E. (1990) Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: A prospective study. Journal of Gerontology, 45, M101-M107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/45.3.M101

- Gustafson, Y., Berggren, D., Brannstrom, B., Bucht, G., Norberg, A., Hansson, L.I. and Winblad, B. (1988) Acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 36, 525-530.

- Magaziner, J., Simonsick, E.M., Kashner, T.M., Hebel, J.R. and Kenzora, J.E. (1989) Survival experience of aged hip fracture patients. American Journal of Public Health, 79, 274-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.79.3.274

- Murray, A.M., Levkoff, S.E., Wetle, T.T., Beckett, L., Cleary, P.D., Schor, J.D., Lipsitz, L.A., Rowe, J.W. and Evans, D.A. (1993) Acute delirium and functional decline in the hospitalized elderly patient. Journal of Gerontology, 48, M181-M186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/48.5.M181

- Allen, J., Koziak, A., Buddingh, S., Laing, J., Buckingham, J. and Beaupre, L. (2012) Rehabilitation in patients with dementia following hip fracture: A systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada, 64, 190-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-06BH

- Bellelli, G., Frisoni, G., Pagani, M., Magnifico, F. and Trabucchi, M. (2007) Does cognitive performance affect physical therapy regimen after hip fracture surgery? Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 19, 119-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03324677

- McGilton, K.S., Davis, A., Mahomed, N., Flannery, J., Jaglal, S., Cott, C., Naglie, G. and Rochon, E. (2012) An inpatient rehabilitation model of care targeting patients with cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatrics, 12, 1-11. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2318/12/21

- McGilton, K.S., Davis, A.M., Mahomed, N., Flannery, J., Jaglal, S., Rochon, E. and Naglie, G. (2013) Evaluation of a patient-centered rehabilitation model targeting older persons with a hip fracture, including those with cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatrics, 13, 136.

- McGilton, K., Wells, J., Teare, G., Davis, A., Rochon, E., Calabrese, S., Naglie, G. and Boscart, V. (2007) Rehabilitation of patients with dementia following a hip fracture. Part I: Behavioural symptoms that influence care. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 23, 161-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.TGR.0000270185.98402.a6

- McGilton, K., Wells, J., Teare, G., Davis, A., Rochon, E., Calabrese, S., Naglie, G. and Biscardi, M. (2007) Rehabilitation of patients with dementia following a hip fracture. Part 2: Cognitive symptoms that influence care. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 23, 174-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.TGR.0000270186.36521.85

- Papadimitropoulos, E.A., Coyte, P.C., Josse, R.G. and Greenwood, C.E. (1997) Current and projected rates of hip fracture in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 157, 1357-1363.

- Wiktorowicz, M.E., Goeree, R., Papaioannou, A., Adachi, J.D. and Papadimitropoulos, E. (2001) Economic implications of hip fracture: Health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporosis International, 12, 271-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001980170116

- Hope, K. (1994) Nurses’ attitudes towards older people: A comparison between nurses working in acute medical and acute care of elderly patient settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20, 605-612. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20040605.x

- Courtney, M., Tong, S. and Walsh, A. (2000) Acute-care nurses’ attitudes towards older patients: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 6, 62-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172x.2000.00192.x

- McKinlay, A. and Cowan, S. (2003) Student nurses’ attitudes towards working with older patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 43, 298-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02713.x

- Kite, M., Stockdale, G., Whitley Jr., B. and Johnson, B. (2005) Attitudes toward younger and older adults: An updated meta-analytic review. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 241-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00404.x

- Armstrong-Esther, C., Sandilands, M. and Miller, D. (1989) Attitudes and behaviours of nurses towards the elderly in an acute care setting. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 14, 34-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03402.x

- Treharne, G. (1990) Attitudes towards the care of elderly people: Are they getting better? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 15, 777-781. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01906.x

- Slevin, O. (1991) Ageist attitudes among young adults: Implications for a caring profession. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 16, 1197-1205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01529.x

- Armstrong-Esther, C. and Browne, K. (1986) The influence of elderly patients’ mental impairment on nurse-patient interaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 11, 379- 387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1986.tb01264.x

- Salmon. P. (1993) Interactions of nurses with elderly patients: Relationship to nurses’ attitudes and to formal activity periods. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 18, 14-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18010014.x

- Borbasi, S., Jones, J., Lockwood, C. and Emden, C. (2006) Health professionals’ perspectives of providing care to people with dementia in the acute setting: Toward better practice. Geriatric Nursing, 27, 300-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.08.013

- McCabe, M.P., Davison, T.E. and George, K. (2007) Effectiveness of staff training programs for behavioral problems among older people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 11, 505-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607860601086405

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Werner, P., Culpepper, W.J. and Barkley, D. (1997) Evaluation of an inservice training program on dementia and wandering. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 23, 40-47.

- Moniz-Cook, E., Agar, S., Silver, M., Woods, R., Wang, M., Elston, C. and Win, T. (1998) Can staff training reduce behavioral problems in residential care for the elderly mentally ill? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13, 149-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199803)13:3<149::AID-GPS746>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Burgio, L.D., Stevens, A., Burgio, K.L., Roth, D.L., Paul, P. and Gerstle, J. (2002) Teaching and maintaining behavior management skills in the nursing home. The Gerontologist, 42, 487-496. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.4.487

- Magai, C., Cohen, C.I. and Gomberg, D. (2002) Impact of training dementia caregivers in sensitivity to nonverbal emotion signals. International Psychogeriatrics, 14, 25- 38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1041610202008256

- McCallion, P., Toseland, R.W., Lacey, D. and Banks, S. (1999) Educating nursing assistants to communicate more effectively with nursing home residents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 39, 546-558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.5.546

- Zimmerman, S., Williams, C.S., Reed, P.S., Boustani, M., Preisser, J.S., Heck, E. and Sloane, P.D. (2005) Attitudes, stress, and satisfaction of staff who care for residents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45, 96-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.96

- Lintern, T., Woods, B. and Phair, L. (2000) Before and after training: A case study of intervention. Journal of Dementia Care, 8, 15-17.

- MacDonald, A. and Woods, R. (2005) Attitudes to dementia and dementia care held by nursing staff in U.K. “non-EMI” care homes: What difference do they make? International Psychogeriatrics, 17, 383-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S104161020500150X

- Gilleard, C. and Groom, F. (1994) A study of two dementia quizzes. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33, 529-534. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01149.x

- Schaefer, J.A. and Moos, R.H. (1993) Relationship, tasks, and system stressors in the health care workplace. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 3, 285- 298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450030406

- GTA Rehab Network (2006) Hip fracture and joint replacements in a changing landscape: Recommendations and Implications. http://www.gtarehabnetwork/publications.asp

- Davis, A., Mahomed, N., Flannery, J., Brien, H. and Saryeddine, T. (2006) Current status and future opportunities for inpatient musculoskeletal rehabilitation: An analysis of supply data and provider viewpoints on future needs. http://www.gtarehabnetwork.ca/uploads/File/reports/rpt-MSK-june06.pdf

- Norbergh, K., Helin, Y., Dahl, A., Hellzen, O. and Asplund, K. (2006) Nurses’ attitudes towards people with dementia: The semantic differential technique. Nursing Ethics, 13, 264-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0969733006ne863oa

- McCormack, B. and McCance, T.V. (2006) Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56, 472-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04042.x

- Alzheimer Society of Canada (2010) Rising tide: The impact of dementia on Canadian society. Executive summary. http://www.alzheimer.ca/en/Get-involved/Raise-your-voice/~/media/Files/national/Advocacy/ASC_Rising%20Tide-Executive%20Summary_Eng.ashx

- Charalambous, A., Chappell, N.L., Katajisto, J. and Suhonen, R. (2012) The conceptualizationand measurement of individualized care. Geriatric Nursing, 33, 17-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.10.001

- Morgan, S. and Yoder, L.H. (2012) A concept analysis of person-centered care. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 30, 6-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0898010111412189

- Penner, L., Ludenia, K. and Mead, G. (1984) Staff attitudes: Image or reality? Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 10, 110-117.