Applied Mathematics

Vol.07 No.09(2016), Article ID:66773,9 pages

10.4236/am.2016.79076

The Game-Theoretical Model of Using Insecticide-Treated Bed-Nets to Fight Malaria

Mark Broom1, Jan Rychtář2, Tracy Spears-Gill3

1Department of Mathematics, City University London, Northampton Square, London, UK

2Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, USA

3Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, USA

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 2 April 2016; accepted 23 May 2016; published 26 May 2016

ABSTRACT

Malaria infection is a major problem in many countries. The use of the Insecticide-Treated Bed- Nets (ITNs) has been shown to significantly reduce the number of malaria infections; however, the effectiveness is often jeopardized by improper handling or human behavior such as inconsistent usage. In this paper, we present a game-theoretical model for ITN usage in communities with malaria infections. We show that it is in the individual’s self interest to use the ITNs as long as the malaria is present in the community. Such an optimal ITN usage will significantly decrease the malaria prevalence and under some conditions may even lead to complete eradication of the disease.

Keywords:

Game Theory, Malaria Prevention, Optimal Strategy, Epidemic Modelling, SIS Model

1. Introduction

Malaria is a vector born disease that can be transmitted to people through mosquito bites, prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. The World Health Organisation estimates that every year nearly one million people die as a result of malaria [1] . A lot of effort has been put into treatment and prevention strategies, and an ambitious goal of organisations such as the World Health Organisation and the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation is the complete elimination of malaria.

One of the key methods of malaria prevention is the use of Insecticide-Treated Bed-Nets (ITNs) that kill and also repel mosquitoes [2] . [3] found that the use of ITNs can reduce malaria cases by 50% and death in children by 20%. The use of ITNs was demonstrated to be very cost-effective, see e.g. [4] - [6] . This is important given both the scale of the problem (about 200 million people are at a very high risk [7] ), and the fact that most of the areas of high malaria prevalence are relatively poor. However, human behavior such as inconsistent usage due to hot weather diminishes the effectiveness of the ITNs.

The impact of ITN usage on the spread of the malaria infection has been recently studied in a series of mathematical models such as [8] - [10] . In particular, [10] developed an ODE model for the effects of ITN on the malaria transmission dynamics and called for a better understanding of the impact of human behavior on the usage.

Game theory is a well suited tool to study human behavior in a quantitative way [11] . Starting by [12] , game theory has been long used in biology [13] , and [14] used it to study vaccination decisions in situation where individuals face a potentially costly preventive action (such as to use an ITN) that can reduce a risk of con- tracting the disease. Game theory has been applied to vaccination against major public health threats [15] - [21] and it is particularly useful because the outcome of the individual decision (to vaccinate or to use an ITN) depends on the decisions of other members of the population because the overall vaccination or ITN usage yields the disease prevalence in the community [22] .

In particular, game theoretical models can be used to understand why in many cases disease eradication can be very hard [14] even when the cost of preventive action is very low [23] . There is often a great incentive to use preventative measures when a disease is at high levels, but when brought below a certain level the incremental benefit of taking the presentative action declines, and so individuals have less incentive to use it. Thus pre- vention can sometimes (but not always) become ineffective before total eradication occurs. In this paper we adapt a non-game theoretical model of ITN usage [10] to study the impact of individual decisions on the effectiveness of ITN usage.

2. The Model

2.1. Model of Malaria Transmission

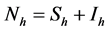

We will use the basic model for the transmission dynamics of malaria infection as presented in [10] . The host population (humans) is divided into two compartments (susceptible and infectious), which are denoted by , respectively. A total host population is given by

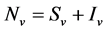

, respectively. A total host population is given by . The vector population (mosquitoes) is also divided into two compartments (susceptible and infectious) which are denoted

. The vector population (mosquitoes) is also divided into two compartments (susceptible and infectious) which are denoted , respectively. The total vector population is given by

, respectively. The total vector population is given by . When a mosquito bites a human, the susceptible human is infected by an infected mosquito with probability

. When a mosquito bites a human, the susceptible human is infected by an infected mosquito with probability  and a susceptible mosquito is infected by an infected human with probability

and a susceptible mosquito is infected by an infected human with probability . Hosts die with natural mortality rates being

. Hosts die with natural mortality rates being  and can also die because of malaria with rate

and can also die because of malaria with rate . Hosts recover with rate

. Hosts recover with rate . Vectors can die with rate

. Vectors can die with rate

(1)

(1)

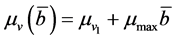

where  is the natural mortality rate of hosts and

is the natural mortality rate of hosts and  is the mortality rate due to ITN use in the population. Here,

is the mortality rate due to ITN use in the population. Here,  denotes the average ITN usage in the population. Each individual chooses its own individual ITN usage

denotes the average ITN usage in the population. Each individual chooses its own individual ITN usage . We assume that all individuals are born as susceptible (with recruitment rates

. We assume that all individuals are born as susceptible (with recruitment rates  and

and

Let

where

number of bites per mosquito per unit of time,

Table 1. Parameters, their description and value. The cost of malaria infection varies by the country an the used treatment, see for example [28] - [32] . Over the life of the ITN, the total cost of infections is more than the cost of the ITN. Moreover, ITNs are often subsidized, so the actual cost of ITN to the individuals is only around $1 per ITN [26] .

proportion of infectious mosquitoes. [10] considers

with

Also, the average force of the infection is

and thus

In the state when malaria reaches equilibrium, [10] evaluates

where

In [10] it is shown that there are potentially two stable steady states of infections and if the malaria was originally common, the stable states yields

Figure 1 shows values of

2.2. Game-Theoretical Model

Let

Such a usage level is stable, because if

Following [14] , we will evaluate

Figure 1. Values of

where

To evaluate

3. Analysis

Given a relatively small value of

There will of course be values of

It follows from (14) that

and thus, by (16), (17),

Because by (16),

and otherwise there is a unique

Moreover, the unique

where

whenever the term under

where

Figure 2. Values of

4. Results

It follows from our analysis that it is in the individual’s best interest to use the ITN as long as there is malaria present in the population. For the parameter values used above, namely

However, the model used shows particular sensitivity to the parameter value

However, in all of the above, we considered that malaria was transmitted between vectors and host during every bite. If we relax this assumption and consider

5. Discussion

In this paper we have considered a game-theoretical model of ITN usage, allowing individuals in the population to decide whether (and how often) they use ITNs. We have shown that optimal behavior from the individual’s perspective leads to the decrease (or even eradication) of the disease, i.e. an optimal outcome from the popu- lation perspective. In particular if it is not possible to eradicate the disease through ITN usage, individuals use ITNs all the time, which leads to the minimum possible level of malaria. If eradication is possible, individuals select a strategy which is approximately at the level that leads to eradication. Moreover, the optimal behavior does not depend on the exact cost of the ITN use (as long as the cost is smaller than the cost of the disease). This type of outcome is not always the case; see for example [14] .

We have seen that individual strategies lead to the eradication level effectively independently of the cost in our case, because individuals have a very high likelihood of getting infected by the disease whenever the disease is present in the population, due to the high rate of infection (

We have assumed that individuals are able to adjust their ITN usage strategy faster than changes in the underlying state of the population, such as the prevalence of the disease, to always obtain the optimal level of

Figure 3. Plots of

Figure 4. Values of

usage. It is clear that they are physically able to do this, because to put up or remove an ITN takes a relatively short time. However, they clearly need sufficient information about the state of the population to make a rational decision to change. What information would they have on which to base their decision? It is clear from Figure 2 that except for

We note that because of the high infection rate, a level of ITN usage close to the eradication level but still below it could formally still lead to high levels of disease prevalence. Thus if individuals had perfect infor- mation about the state of the population they could choose their strategies to achieve the precise level of the equilibrium strategy, which would lead to some intermediate level of infection between 0 and 1. It is our assumption in this paper that they cannot do this precisely. In any case natural variations within the real popu- lation parameters, would mean that the exact value of this critical level would be subject to some fluctuation. The consequence is that the chosen strategy is sufficiently close to the eradication level, that there is a good chance of such eradication occurring, on the assumption that individuals play a fixed bed-net usage strategy.

In reality, it may be that the level of malaria will not have enough time to tend to 0 before individuals in the population notice the low level and give up the use of ITNs. Thus if the malaria level is significantly different to the equilibrium level from our analysis, individual behaviour will prevent it from being eliminated. Thus a more complex dynamically coupled model of the evolution of ITN usage and malaria level may be needed to decide the precise behaviour at such intermediate levels of infection.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Simons Foundation grant #245400 (Jan Rychtář).

Cite this paper

Mark Broom,Jan Rychtář,Tracy Spears-Gill, (2016) The Game-Theoretical Model of Using Insecticide-Treated Bed-Nets to Fight Malaria. Applied Mathematics,07,852-860. doi: 10.4236/am.2016.79076

References

- 1. WHO (2005) World Malaria Report.

- 2. Raghavendra, K., Barik, T.K., Niranjan Reddy, B.P., Sharma, P. and Dash, A.P. (2011) Malaria Vector Control: From Past to Future. Parasitology Research, 108, 757-779.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-2232-0 - 3. Lengeler, C. (2004) Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets and Curtains for Preventing Malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, Article ID: CD000363.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd000363.pub2 - 4. Goodman, C.A. and Mills, A.J. (1999) The Evidence Base on the Cost-Effectiveness of Malaria Control Measures in Africa. Health Policy and Planning, 14, 301-312.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapol/14.4.301 - 5. Goodman, C.A., Coleman, P.G. and Mills, A.J. (1999) Cost-Effectiveness of Malaria Control in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet, 354, 378-385.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02141-8 - 6. White, M.T., Conteh, L., Cibulskis, R. and Ghani, A.C. (2011) Costs and Cost-Effectiveness of Malaria Control Interventions—A Systematic Review. Malaria Journal, 10, 1475-2875.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-337 - 7. Miller, J.M., Korenromp, E.L., Nahlen, B.L. and Steketee, R.W. (2007) Estimating the Number of Insecticide-Treated Nets Required by African Households to Reach Continent-Wide Malaria Coverage Targets. JAMA, 297, 2241-2250.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.20.2241 - 8. White, L.J., Maude, R.J., Pongtavornpinyo, W., Saralamba, S., Aguas, R., Van Effelterre, T., Day, N.P.J. and White, N.J. (2009) The Role of Simple Mathematical Models in Malaria Elimination Strategy Design. Malaria Journal, 8, 212.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-8-212 - 9. Chitnis, N., Schapira, A., Smith, T. and Steketee, R. (2010) Comparing the Effectiveness of Malaria Vector-Control Interventions through a Mathematical Model. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 83, 230.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0179 - 10. Agusto, F.B., Del Valle, S.Y., Blayneh, K.W., Ngonghala, C.N., Goncalves, M.J., Li, N.P., Zhao, R.J. and Gong, H.F. (2013) The Impact of Bed-Net Use on Malaria Prevalence. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 320, 58-65.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.12.007 - 11. Von Neumann, J. and Morgenstern, O. (2007) Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (Commemorative Edition). Princeton University Press.

- 12. Smith, J.M. and Price, G.R. (1973) The Logic of Animal Conflict. Nature, 246, 15-18.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/246015a0 - 13. Broom, M. and Rychtá?, J. (2013) Game-Theoretical Models in Biology. CRC Press.�

- 14. Bauch, C.T. and Earn, D.J.D. (2004) Vaccination and the Theory of Games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 13391-13394.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403823101 - 15. Bauch, C.T., Galvani, A.P. and Earn, D.J.D. (2003) Group Interest versus Self-Interest in Smallpox Vaccination Policy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 10564-10567.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1731324100 - 16. Bauch, C.T. (2005) Imitation Dynamics Predict Vaccinating Behaviour. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272, 1669-1675.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3153 - 17. Galvani, A.P., Reluga, T.C. and Chapman, G.B. (2007) Long-Standing Influenza Vaccination Policy Is in Accord with Individual Self-Interest but Not with the Utilitarian Optimum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 5692-5697.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0606774104 - 18. Shim, E., Kochin, B. and Galvani, A. (2009) Insights from Epidemiological Game Theory into Gender-Specific Vaccination against Rubella. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering: MBE, 6, 839-854.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2009.6.839 - 19. Shim, E., Grefenstette, J.J., Albert, S.M., Cakouros, B.E. and Burke, D.S. (2012) A Game Dynamic Model for Vaccine Skeptics and Vaccine Believers: Measles as an Example. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 295, 194-203.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.11.005 - 20. Crawford, K., Lancaster, A., Oh, H. and Rychtá?, J. (2015) A Voluntary Use of Insecticide-Treated Cattle Can Eliminate African Sleeping Sickness. Letters in Biomathematics, 2, 91-101.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23737867.2015.1111777� - 21. Sykes, D. and Rychtá?, J. (2015) A Game-Theoretic Approach to Valuating Toxoplasmosis Vaccination Strategies. Theoretical Population Biology, 105, 33-38.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tpb.2015.08.003� - 22. Shim, E., Chapman, G.B., Townsend, J.P. and Galvani, A.P. (2012) The Influence of Altruism on Influenza Vaccination Decisions. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 9, 2234-2243.

- 23. Geoffard, P.-Y. and Philipson, T. (1997) Disease Eradication: Private versus Public Vaccination. The American Economic Review, 87, 222-230.

- 24. Teboh-Ewungkem, M.I., Podder, C.N. and Gumel, A.B. (2010) Mathematical Study of the Role of Gametocytes and an Imperfect Vaccine on Malaria Transmission Dynamics. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 72, 63-93.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11538-009-9437-3 - 25. Bowman, C., Gumel, A.B., van den Driessche, P., Wu, J. and Zhu, H. (2005) A Mathematical Model for Assessing Control Strategies against West Nile Virus. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 67, 1107-1133.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bulm.2005.01.002 - 26. Guyatt, H.L., Kinnear, J., Burini, M. and Snow, R.W. (2002) A Comparative Cost Analysis of Insecticide-Treated Nets and Indoor Residual Spraying in Highland Kenya. Health Policy and Planning, 17, 144-153.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapol/17.2.144 - 27. Mulligan, J.-A., Yukich, J. and Hanson, K. (2008) Costs and Effects of the Tanzanian National Voucher Scheme for Insecticide-Treated Nets. Malaria Journal, 7, 32.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-32 - 28. Asenso-Okyere, W.K. and Dzator, J.A. (1997) Household Cost of Seeking Malaria Care. A Retrospective Study of Two Districts in Ghana. Social Science & Medicine, 45, 659-667.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00383-8 - 29. Akazili, J., Aikins, M. and Binka, F.N. (2008) Malaria Treatment in Northern Ghana: What Is the Treatment Cost per Case to Households? African Journal of Health Sciences, 14, 70-79.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajhs.v14i1.30849 - 30. Mutabingwa, T.K. (2005) Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies (ACTs): Best Hope for Malaria Treatment but Inaccessible to the Needy! Acta Tropica, 95, 305-315.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.06.009 - 31. Whitty, C.J.M., Chandler, C., Ansah, E., Leslie, T. and Staedke, S.G. (2008) Deployment of ACT Antimalarials for Treatment of Malaria: Challenges and Opportunities. Malaria Journal, 7, S7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-S1-S7 - 32. Lubell, Y., Reyburn, H., Mbakilwa, H., Mwangi, R., Chonya, S., Whitty, C.J.M. and Mills, A. (2008) The Impact of Response to the Results of Diagnostic Tests for Malaria: Cost-Benefit Analysis. BMJ, 336, 202-205.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39395.696065.47 - 33. Killeen, G.F., Kihonda, J., Lyimo, E., Oketch, F.R., Kotas, M.E., Mathenge, E., Schellenberg, J.A., Lengeler, C., Smith, T.A. and Drakeley, C.J. (2006) Quantifying Behavioural Interactions between Humans and Mosquitoes: Evaluating the Protective Efficacy of Insecticidal Nets against Malaria Transmission in Rural Tanzania. BMC Infectious Diseases, 6, 161.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-6-161