1. Introduction

The blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) a tetraploid perennial, rhizomatous, cross-pollinated shrub [1], is a commercially important crop worldwide, and Chile is one of the main producers and exporting countries [2]. The high content of antioxidant phenolic compounds, anthocyanins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids [3] confers to blueberries both great health maintenance benefits and potential therapeutic values [4,5].

Conventional blueberry propagation through stem or rhizome cuttings is a relatively easy task. Nevertheless, tissue culture propagation has been established in order to reach genetic uniformity in the planting materials and to overcome problems: a) the variations in fruit characteristics originating from diminution in fruit yields [6], and b) the precocity of flowering, which delays the establishment of plantings [7]. Thus, conventional micropropagation of V. angustifolium based in gelled medium has been established and reported [8-11].

In addition, bioreactor technology has been introduced for mass propagation in different plant species [12-17]. In the case of lowbush blueberry (V. angustifolium Ait.), a protocol using RITA® bioreactors combined with semisolid gelled medium has been developed for the cultivar Fundy and for two wild clones [18]. Because the high production costs render conventional micropropagation systems (agar-based) less suitable for large-scale production, liquid cultures and automation has the potential to resolve the manual handling of the various stages of micropropagation [15]. Bioreactor cultures also permit an additional management of both physical and chemical environments, such as air exchange, photosynthetic photon flux, and CO2 content, resulting in more efficient plant performance during the in vitro micropropagation [19-21].

The effects of natural ventilation on leaf ultrastructure of plants cultured in vitro demonstrated that characteristics, such as the epidermal cell walls, cytoplasm and, thylakoid stacking and distribution were similar to those of plants from in vivo conditions [22]. It was previously stated that leafy or chlorophyllous explants of a number of in vitro plant species had high photosynthetic ability while their growth and development occurred on sugarree medium rather than on sugar-containing medium, evidencing that environmental factors, such as CO2 concentration, light intensity, and relative humidity, promoted photosynthesis and transpiration of explants/hoots/ lantlets in vitro [23].

In the present study, for the first time, blueberry micropropagation was established in TIBs (two separate transparent containers). Bioreactors were standardized under high photon flux and CO2-rich environment. Data confirmed the TIBs plasticity as an integrative tool toward a high-scale production of blueberry plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Stocks of blueberry plantlets of the genotypes Biloxi, Sharp Blue and Brillita were established in vitro following the method of Debnath [17]. Essentially, shoot tips (~5 cm) were surface disinfected in a 10% commercial solution NaOCl plus 0.1% Tween 20 (15 min.) followed by a treatment in 70% ethanol (5 min.) and then three rinses in sterile distilled water. Shoot tips were cultured for 8 weeks in McCown’s Woody Plant (WP) medium [24]. Culture medium was solidified with 8 gr/l agar and the pH was adjusted to 5.2 before autoclaving at 121˚C. Both sucrose and N6-[2-isopentenyl] adenine (2iP) were supplemented as the genotype requirement: Biloxi (35 gr/l sucrose, 2 mg/l 2iP); Sharp Blue (30 gr/l sucrose, 3 mg/l 2iP); Brillita (35 gr/l sucrose, 3 mg/l 2iP). Plant cultures were maintained at 23˚C ± 2˚C, for a 16 h photoperiod under a combination of both natural light and cool-white fluorescent tubes at a light intensity of 60 mM m−2·s−1.

2.2. Establishment of Bioreactor Cultures

Two-vessel bioreactors were set up following established designs [25-27]. A total of 10 internodes (2 buds) from vigorous blueberry plants of 20 days old (after subculture) were transferred to a sterile transparent bottle (1 L capacity). The couple bottle contained 250 ml of the same culture medium, but liquid, as above described per each genotype. The experimental factors were the following: a) Genotype (Biloxi; Sharp Blue; Brillita); b) Sucrose concentration in TIBs (35 gr/l or 30gr/l depending on genotype; 20 gr/l); c) Immersion frequency (3 min each 8 h; 3 min. each 6 h); d) In vitro multiplication approach (TIBs; agar-base + sucrose as previously described in plant materials); e) Explants management (internodes with leaves; internodes without leaves). Air quality in the TIBs working station was improved with 0.4 MPa CO2, and bioreactors were maintained during 35 days at 23˚C ± 2˚C under a combination of both natural light and cool-white fluorescent tubes at a light intensity of 60 mM m−2·s−1. The experiments were replicated three times.

2.3. Acclimatization

Blueberry plants multiplied using both TIBs and agarbase (control) approaches were carefully separated, washed in water and, planted in 128-cell plug trays (cell volume 25 cm3) containing a mixture of composted pine bark and zeolite (2:1). Trays were maintained in the greenhouse, and the relative humidity was gradually reduced: 90% ® 80% ® 70% in 10 day intervals. Luminosity was 100 mM m−2·s−1 under the natural photoperiod of January-February, latitude 35˚30'-altitude 71˚30', locality of Talca, Chile.

2.4. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

The following variables were considered after the micropropagation cycle (35 days): total number of internodes, plant size (height), number of internodes per plant, plant number (in vitro shooting). The adaptability rate was determined after 30 days of planting (acclimatization). Multivariate principal component classification analysis and discriminate analysis [28] were performed using the STATISTICA V.6 software package (STATSOFT, Inc., 2003). Variance was calculated for the micropropagation traits related to productivity and was compared between treatments using Bartlett’s homogeneity of variances test.

3. Results

A new procedure for blueberry micropropagation in programmed bioreactors (TIBs based on two separate bottles) was developed for the commercial genotypes Biloxi, Sharp Blue and Brillita. For a statistical characterization of the micropropagation process, a principal component analysis was conducted, including data from both the in vitro and the acclimatization stages (Table 1). Component 1 (C1) grouped 64.08% of the total variability, while the first two components accounted for 86.97%.

Component 1, on the X-axis, was represented by the effects of genotypes (G) with negative correlation with the in vitro approach (IA). In this case, results showed that variables including total internodes (TI), plant size (PS), number of internodes per plant (NIP), plant number (PN), and in vitro shooting (IS) interacted positively altogether supporting the micropropagation rate. The variables of growing rate (GR) and greenhouse adaptability were found to negatively interact in C1.

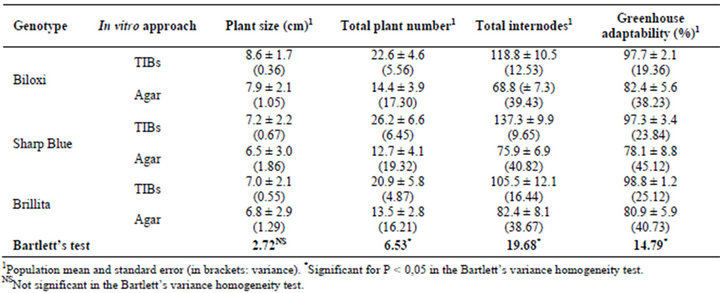

Table 1. Multivariate classification analysis of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) micropropagation in Temporary Immersion Bioreactors (TIBs).

Component 2, contributing 22.89% of variability (Yaxis), was represented by the interrelation between the factors of in vitro approach (IA) and sucrose concentration (SC). The Immersion frequency also contributed to C2. In general, the factor of in vitro approach (IA) was represented in both C1 and C2 components, while the explants management (EM) had no significant contribution to the principal components.

Graphic representation of C1-C2 presents both unique and overlapping positions. The plot of the two principal components (Figure 1) demonstrated three clusters corresponding with the blueberry genotypes. Within each cluster, plants micropropagated in agar-base medium (conventional approach as control treatments) grouped separately from those plants multiplied in TIBs.

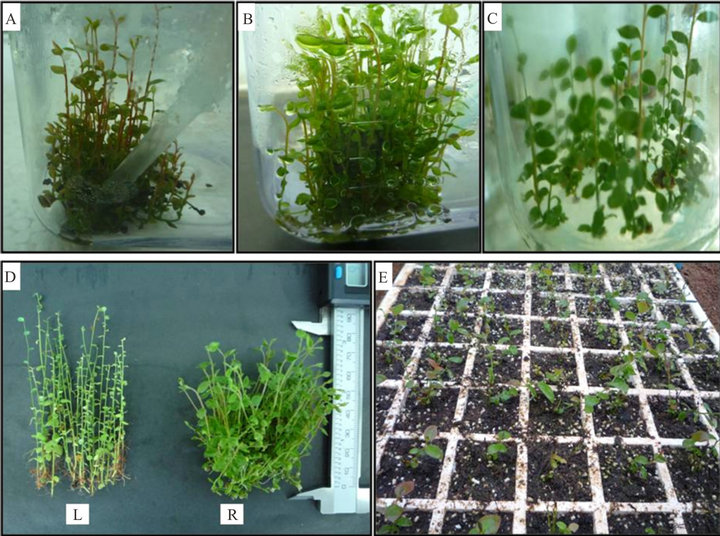

Below, the images in Figure 2 show the results on the establishment of a new approach for V. corymbosum (L.) micropropagation in TIBs. Blueberry plants grew and multiplied (Figures 2(A) and (B)) in a sucrose-reduced culture medium, with CO2-rich and high luminosity environment. As expected, explants cultured in conventional agar medium showed a sufficient plant development (growth), but the in vitro secondary shooting was low down (Figure 2(C)), diminishing the total number of internodes. For all Biloxi, Sharp Blue and Brillita genotypes, overall variables related to the micropropagation rate were demonstrated superior in TIBs cultures compared to those for plants propagated in agar-base medium (Table 2, Figure 2(D)).

After transfer to the greenhouse, both growing and adaptability were evaluated in the TIBs-micropropagated plants. Results showed that more than 97% of the blueberries propagated in TIBs had adapted and showed a higher growing rate in comparison with plants from agarbase cultures (Table 2; Figure 2(E)). As was predictable, control plants propagated in agar-based medium (35 or 30 gr/L sucrose, without CO2-rich air) demonstrated approximately eighty percent adaptability to greenhouse conditions. Results could be explained because the environmental conditions (reduced sucrose 20 gr/L, CO2-rich air, and higher luminosity) during TIBs culture might be influencing plants toward a photomixotrophic stage, which possibly primes blueberry plants for the acclimatization step. To reach the highest adaptation rates of vitroplantlets, an accurate management of the environmental factors influencing the plant evapotranspiration should be also considered. In this case, enclosed in a high natural luminosity period, the humidity was reduced gradually in 10 day intervals during 30 days.

The statistical analysis of micropropagation traits related to productivity shows the large variances for blueberry plants multiplied through the agar-base approach (Table 2). The plant size variance was not significant between the in vitro approaches in the studied genotypes. Meanwhile the Bartlett’s test showed significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05) for the variables total plant number, total internodes and greenhouse adaptability. Summarizing, the higher results for traits linked to plant micro multiplied in CO2-rich TIBs propagation yields were demonstrated in blueberries

4. Discussion

For the first time, an efficient micropropagation system based in two-vessel TIBs has been carried out using three commercial blueberry genotypes. TIBs may be considered as a natural tissue-culture approach [29], and it has been a reliable tool in this research. The two-vessel TIBs (one holds the liquid medium and the other the cultures of the plants) proved to be a more flexible approach with

Figure 1. Graphic representation of the principal components analysis of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) micropropagation in Temporary Immersion Bioreactors (TIBs). Conventional agar-base micropropagation was the control treatment for each genotype.

Table 2. Productive traits recorded during blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) micropropagation in CO2-rich TIBs and agar-base (control treatment). Both cultures were inoculated with 10 separate internodes per replica.

Figure 2. Micropropagation of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) in bioreactors. (A) TIBs multiplying plants of cv. Biloxi after 25 days of culture; (B) plants of cv. Sharp Blue of 35 days of culture; (C) Control plants of cv. Sharp Blue growing in agar-base treatment (conventional); (D) Comparison of the propagation rates of blueberry plants (cv. Brillita) between conventional; (L) TIBs; (R) technologies; E. Micropropagated blueberry plants (cv. Biloxi) after 25 days of planting in greenhouse.

relatively simple construction and operational ease. Furthermore, TIBs might be optimized using a spectrum of glass/plastic containers and thus appropriate for largescale plant micropropagation facilities [30]. Previously Debnath [18] reported about lowbush blueberry micropropagation using RITAÒ bioreactors (VITROPIC, SaintMathieu-de-Treíviers, France; [31]), which could be considered as a more expensive alternative. The current TIBs involve much lower cost at the outset and perhaps less maintenance and supervisory cost during the propagation period as well.

Blueberry cultures in a controlled environment with CO2-enrichment, higher luminosity, and sucrose-reduced medium should be considered as a novel advance for micropropagation of shrub crops. Altogether, results demonstrate the plasticity of the TIBs technology to manage the major environmental factors toward an improvement of plant physiological processes, in this case the in vitro photosynthesis. Previously both the enhancement of the plant-air contact in a 0.4 MPa CO2 enrichment atmosphere and placement under a light intensity of 110 mM m−2·s−1 were significant factors to improve the phenolic metabolites secretion in sugarcane multiplication in TIBs [19]. The differential expression of Rubisco transcripts in increased CO2 concentration in parallel with a reduction of sucrose in the culture medium indicated the change from a heterotrophic to a photomixotrophic metabolic stage in vitro plantlets micropropagated in TIBs [21].

Blueberries propagated in TIBs showed higher adaptability and growing rates than those cultured by the conventional approach when plants were transferred to greenhouse conditions. This fact should be a measure of the occurrence of a photomixotrophic stage that enhances, or primes, the vitroplantlets cultured in TIBs. Priming of in vitro propagules refers to the manipulation of the growing environment, prior to and upon transplanting, and is an integral part of tissue culture propagation [32, 33]. The CO2 supply during the proliferation and multiplication stages in media with sucrose have been applied in bioreactors indicating increases in the plant growth during acclimatization and transplanting [29,34].

In the case of fruit trees, there are a few reports on this matter. The effects of different growth conditions (ventilated and closed vessels, medium with 0, 15, and 30 g dm−3 sucrose) during proliferation of quince (Cydonia oblonga Mill.) demonstrated a significant correlation between sucrose content in the leaves of donor shoots and the number of regenerated somatic embryos. This correlation suggests that identification of biochemical and physiological characteristics of donor shoots associated with increased regeneration ability might be helpful for improving morphogenesis in plant tissue culture [35].

In another example, Morini and Melai [36] studied the daily dynamics of CO2 concentration in the culture vessels and the photoautotrophic/photomixotrophic growth capacity of apple (Malus pumila hybrid MM106 paradisiaca × Northern Spy) under photon flux density of 210 ± 5 mmol m−2·s−1. They conclude that the photoautotrophic growth in the absence of sucrose was satisfactory, and the values of fresh and dry mass were equal to those obtained with sugar-enriched medium. Moreover, the induction of photoautotrophy also substantially improved the growth in cultures on sugar-enriched medium. Since in these experiments the photoperiod was shorter (8 h) than that normally used (16 h), they hypothesized that photoautotrophic growth should increase due to CO2 enrichment with the application of longer photoperiods.

In this paper, CO2 concentrations in TIBs were similar to those reported for sugarcane [19,21]; however, both sucrose reduction and luminosity were dissimilar according to the blueberry genotypes, and to the laboratory facilities, respectively. Considering photosynthesis as a complex process involving a range of environmental factors determining carbon assimilation, these results should be the tip of the iceberg toward further research on V. corymbosum (L.) micropropagation in TIBs, in this case as model specie of shrub crops.

For the first time, micropropagation of blueberries has been conducted in TIBs (two-bottles) under photomixotrophic conditions. An increase in both plant multiplication rate and total number of internodes has been demonstrated in three commercial genotypes. In parallel, efficient plant rooting and greenhouse adaptability has been obtained without growth regulator treatments (in vitro or ex vitro). Results pave the way for a further research to standardize micropropagation protocols to other woody plants and shrub crops.

5. Acknowledgments

We give thanks to Anne Bliss, Ph.D. (University of Colorado, USA) for the language revision and copyediting of the manuscript and the Regional Government of Maule (Chile) for financial support.