A Critical Analysis of a State Education Agency’s Equity Policy Framework ()

1. Introduction

This qualitative research study explores a State Education Agency’s (SEA) policy designed as a state-level intervention to address state-specific equity gaps as defined by federal and state policy. Equity gaps in education are a long-standing problem anchored in the dimensions of fairness and inclusion ( Field et al., 2007 ). Equity is embedded into federal and state policy beginning with the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA). ESEA has been reauthorized as the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) and again as the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (ESSA) ( United States Department of Education, 2017 ). Educational Equity is a phenomenon that continues to influence federal policies and carries into state-level policies.

The federal Excellent Educators for All (EEA) policy is a provision of the ESSA mandating that states determine whether low-income students and minority students in Title I schools are served at disproportionate rates by ineffective, out-of-field, or inexperienced teachers, framed as equity gaps. The purpose of the research is to develop an in-depth analysis of how the SEA policy is currently addressing the existing equity gaps in economically disadvantaged and minority students’ access to effective educators. As a result of the federal EEA policy requirement, the SEA of Texas, the Texas Education Agency (TEA), initiated the Texas Equity Toolkit (TET) policy framework as a policy intervention to address the equity problems in Title I schools.

The TET policy framework is only applicable to Title I schools. The Title I school designation is based on the number of low-income students who are considered at-risk for school achievement. To be considered a Title 1 school, a minimum of 40% of the students must qualify for free or reduced lunch. The districts then choose to participate in the Title I, Part A program which provides funds and resources used to improve the quality of education programs and ensure students from low-income families have opportunities to meet challenging state assessments ( Texas Education Agency, 2015 ). The TEA defines an economically disadvantaged student as one who is eligible for free or reduced-price meals under the National School Lunch and Child Nutrition Program ( Texas Education Agency, 2015 ). Minority Students means students who are members of a racial or ethnic group other than the racial or ethnic group that represents most of the state’s population ( Merriam-Webster, n.d. ).

This article analyzes the TET policy to practice from a qualitative view using an educational equity framework. The overarching goal of the policy is to close the achievement gap between high and low-performing students, emphasizing the achievement gaps between minority and non-minority students. Mitra (2018) states, “Ultimately issues of equity relate to issues of power and oppression” (p. 172). The emphasis on closing achievement gaps would imply that there is a balance of power rather than the current imbalance or inequities that have been created throughout history. Educational inequality is one of the most relevant issues in the history of the sociology of education, even if research has focused on the analytical question regarding the cause of inequalities or their change over time and space, rather than on the normative one including what people think about the relationship between inequality and equity ( Benadusi, 2002 ). The key factors or building blocks of educational equity within the TET policy include access to effective teachers who promote higher-order thinking skills for all students, multiple measures to assess student performance, progress, equitable learning strategies, and evidence-based interventions resulting in policy to practice sustainability.

2. Educational Equity

Equity is defined as justice according to natural law or right; specifically: freedom from bias or favoritism ( Merriam-Webster, n.d. ). Equity is a core value utilized in education to guide policy development and opportunities for students. Educational equity means that every child receives what they need to develop to their full academic and social potential ( National Equity Project [NEP], n.d. ). Equity is often confused and interchangeably used with the term equality which is defined as the effect of treating each as without difference ( Diffen LLC, n.d. ). “While education was not to be a direct target of federal policy, education has long been viewed as a policy space in which governments attempt to address social issues” ( Mitra, 2018: p. 5 ). Educational equity is framed as a social issue embedded in policies throughout educational and political systems. Educational equity is important from policy to practice because historically the most marginalized students are paired with the most ineffective teachers. The TET policy defines effective teachers as those who have been in education for more than one year and are certified in the content area in which they teach ( TET, 2019 ). Educational equity is at the core of the TET policy because the goal is to pair the most marginalized students with the most effective teachers.

3. TET Policy Framework

The TET policy framework is designed as an intervention to address state-specific equity gaps in hopes of closing the fifty-year-old equity gap between economically and non-economically disadvantaged students within the state of Texas. The state equity report identifies that the largest gaps in student performance as well as access to effective educators exist between economically disadvantaged students and non-economically disadvantaged students ( Texas Education Agency, n.d. ). While public schools have autonomy as to how they educate their students, they remain accountable for educating all students using high academic standards and outcomes regardless of the characteristics of the students ( Intercultural Development Research Association [IDRA], 2020 ). The TET policy framework provides schools with an opportunity to address equity problems within parameters and guidelines that involve intentional strategies and stakeholder support. The TET policy is the intervention offered to address the problem of inequitable access to effective educators as outlined within the EEA policy for economically disadvantaged and minority students enrolled in Title I schools who are served at a disproportionate rate by ineffective, out-of-field, or inexperienced teachers ( Texas Education Agency, 2015 ).

The TET policy involves a three-step process:

Step 1. Review current data and conduct a root cause analysis.

Step 2. Select strategies and plan for implementation.

Step 3. Monitor the progress and fidelity of implementation.

Step one requires stakeholders to conduct a root cause analysis by generating perceived reasons why equity gaps exist in the district if there are identified equity gaps as determined by the criteria set by the Texas Education Agency. Step two involves selecting strategies that could potentially improve the equity gaps within the district directly targeted to improve equitable access and consists of the planning for implementation of the process as measured by a three to five-year goal with yearly data review. Step three requires districts to monitor strategy implementation and progress every six months and adjust or continue the plan implementation based on data. The intent is to close the equity gaps slowly and intentionally promote sustainable practices. Once this process is complete, districts submit the equity plans to the TEA for review and then provide the data to the USDE in alignment with the EEA policy requirements. This process is used regardless of the size, the location, or the identified needs of the district. While there is a place for equality in education, not all students begin their educational journey on an equitable playing field thus resulting in educational policies meant to influence student access to time, resources, and opportunities that would allow them to succeed at their highest potential. The result of the educational inequities leads to educational equity problems resulting in federal and state statutes, policies, and mandates as proposed solutions to equity gaps. Although the TET framework has a concise three-step process to help districts address issues of equity, the research shows that the lack of policy-to-practice implementation creates sustainability gaps.

4. Educational Equity Policy to Practice

Educational inequity continues to be created when the practice does not mirror the intent of the policy. Sustainability focuses on whether the reform continues beyond the initial infusion of resources and support ( Coburn, 2003 ). The lack of policy-to-practice creates sustainability gaps. While there have been changes in educational policies that address equity gaps, the gap in achievement among economically and non-economically disadvantaged students continues to widen, implying that the practices within the policies are either ineffective or there are gaps in the sustainability of the practices ( Field et al., 2007 ). These ineffective practices further the sustainability gaps resulting in the inability to close an equity gap.

Equity is a reform that is currently in the realm of sustainability. Reforms solve long-standing problems, reveal, and define new problems, and address strong pressure to make a change ( Mitra, 2018 ). There are a multitude of researchers who study equity through several lenses, and while no solid solutions exist, EEA supports and mandates that reform occur ( Skrla et al., 2009 ). Equitable access to resources including effective teachers, curriculum, instruction, and funding, changes every year creating barriers to sustainable practices. Pressure to address these inequities continue and are led by many actors including school personnel, parents, legislatures, advocacy groups, and multiple stakeholders ( Mitra, 2018 ). SEAs are mandated to report to the United States Department of Education (USDE) the equity gaps that do exist, and while this may be time-consuming and expensive, the data demonstrates that gaps are evident, but also that states are attempting to address this long-standing problem. Historically, many educational equity policies were tried and failed to close equity gaps ( Hudson et al., 2019 ). The true test of sustainability will occur when the USDE no longer provides infrastructure support including resources, funding, or expectations of states to support the equitable policy mandates ( TESF, 2019 ).

The TET process for addressing equity is structured, and stakeholders are expected to participate in the identifying, addressing, and implementation of the strategies. They are expected to support the initiative to close equity gaps by collaborating, planning, and creating professional learning communities that share the same goal for students. These actions and mandates are evidence of an attempt to build sustainable practices. The TET policy framework involves an intervention process designed to address equitable practices to access effective educators for marginalized students ( Texas Education Agency, 2015 ).

5. Methods

This qualitative research analyzes how the TET policy addresses existing equity gaps and influences the practice of pairing effective educators with economically disadvantaged students in rural, Title I school districts. Creswell & Poth (2018) states qualitative research involves an “approach in which the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system or multiple bounded systems over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information” (p. 96). In this research study, the investigator explores school districts’ contemporary bounded systems within the TET policy involving multiple stakeholders’ attempts to close equity gaps. The equity gaps are defined by the federal Excellent Educators for All (EEA) initiative as the unequal distribution of resources, including highly qualified or effective educators, curriculum, and funding disparities for marginalized student populations ( USDE, 2017 ). This study analyzes the TET policy’s influence on the implementation of placing marginalized students with highly qualified educators. The researcher uses qualitative data triangulation including 1) semi-structured interviews with district-level stakeholders, 2) observations and memo-writing, and 3) artifacts and low-inference evidence to analyze what factors need to be present for the TET policy to influence and/or close equity gaps. The qualitative data triangulation is structured to help assess how the TET policy helps or hinders the practice of providing economically disadvantaged students in rural, Title I, school districts with access to the most effective teachers leading to more equitable opportunities in the classroom.

6. Semi-Structured Interviews

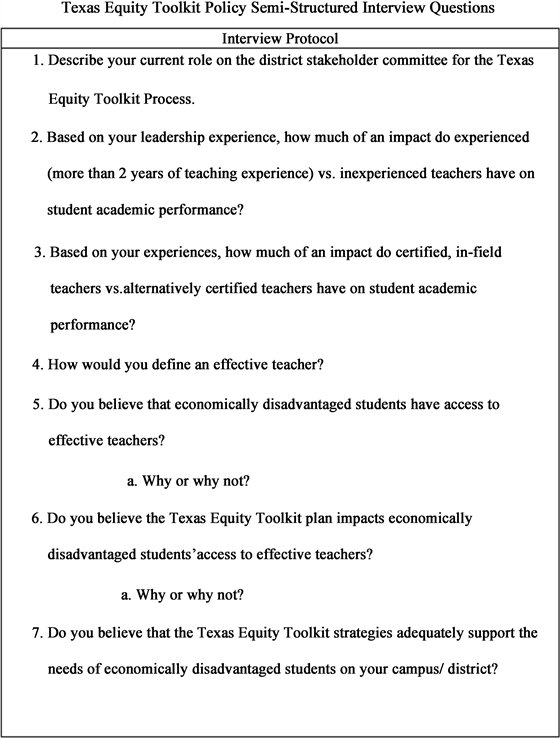

The semi-structured interview process involves purposeful sampling which includes district-level stakeholders from three to five rural, Region 17 districts. The philosophical approach of methodological assumptions is used to guide the qualitative case study. The researcher takes an inductive approach to the qualitative study by creating a data collection plan to privy the semi-structured interview responses and adjusts interview questions along the way based on themes and patterns that arise throughout the study ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 ). The purpose of the semi-structured interviews is to listen, observe, and collect data about how the TET policy’s three-step process implementation influences economically disadvantaged students’ access to effective teachers. As the interview question responses are analyzed, common trends in the data are used to identify findings. The interview questions require the interviewee’s perception of the effectiveness and impact of the Texas Equity Toolkit (TET) process and allow the researcher to analyze how the policy aligns to practice.

The following is an example of the Interview Protocol Questions asked to the qualitative research participants:

7. Observations and Memo Writing

The observations and memo writing process involve collecting participants’ responses to the semi-structured interview questions from district-level stakeholders from three to five rural, Region 17 districts. The researcher records responses and observations using the analytic memo writing method ( Creswell & Poth, 2018 ). This note-taking method allows the data to be collected using coding, ideas about the data, and raw data collection in an interpreted and analyzed form. Jotted notes from the interviews and field notes are reviewed and organized. The interview observations and memo-writing are used to collect additional research data during the semi-structured interviews to eliminate bias as the interviews are in process. The observations and memo-writing notes assist in answering the research questions by evaluating the TET policy’s impact on closing equity gaps and providing access to effective teachers for economically disadvantaged students. The observations and memo writing allow the researcher to analyze the effectiveness and impact of the Texas Equity Toolkit (TET) process and how the policy aligns to practice.

8. Artifacts and Low-Inference Evidence

The artifacts and low-inference evidence involve collecting observable data found within each district’s equitable school plan resulting from the TET policy. The plan includes identifying an equity-based problem, creating a goal to address the problem, identifying the root cause of the problem, and choosing equitable strategies to address the problem. The districts are required to monitor, review, and refine the plan based on district-level data findings. The plan is created during the district stakeholder meetings; therefore, those who are interviewed also participate in the districts’ TET planning process. The artifacts and low-inference evidence are used to triangulate the data to confirm findings or allow for the exploration of new findings regarding the impact of the TET policy on the closing of gaps and access to effective teachers for economically disadvantaged students in rural, Title I, school districts. The artifacts include the raw district-level data used to create goals for closing the equity gaps, documents from each step of the planning process including the problem identification, root cause analysis, and strategy overview as well as the initial equity plan and the quarterly reporting used to measure progress towards the overall goals. The artifacts are used to draw low-inference evidence themes and findings.

9. Data Coding Analysis

The researcher analyzes the 1) semi-structured interviews with district-level stakeholders, 2) observations and memo-writing, and 3) artifacts and low-inference evidence using a qualitative coding system to identify findings and themes. Coding is the process that allows for a compilation of labeling and organizing qualitative data to identify the different themes and relationships between the data. The coding system allows for the identification or confirmation of findings in the data. The artifacts and records will be analyzed using similar coding systems. An inductive and deductive coding key is used to chart and record responses and observations and analyze the records. The data coding analysis allows the researcher to evaluate the alignment and effectiveness of the TET policy to practice.

10. Findings/Themes

Semi-Structured Interview Findings. The first qualitative finding anchors into the theme that the TET policy is a compliance-driven tool used to address equity gaps. The interviewees expressed that there are several accountability initiatives that require various plans, making implementation difficult even when the intention is good and suggested that maybe a combination of initiatives addressing several compliance standards could be good for districts. “If schools didn’t have to make so many plans when they are in trouble, then the plans would be used as intended and would hopefully be more impactful. Instead, we tend to just make a lot of plans”, is stated in one of the interviews. The planned development and implementation are anchored into the characteristics of the theories of loose coupling and decentralization, which require accountability regarding the evaluation of progress, feedback cycles, and adjustments to the plan when necessary ( Bolman & Deal, 2017 ). The administrators are responsible for monitoring the plan to change outcomes and close equity gaps for economically disadvantaged students, which is difficult when the plans are perceived to be compliance-based. The evaluation of the process indicates that the lack of faithfully implementing the strategies or adjusting the plan as outlined within the TET policy to help economically disadvantaged students access effective teachers results in sustainability gaps.

Observation and Memo-Writing Findings. A second qualitative finding includes the theme that equity is perceived as how students are treated based on race rather than based on student needs. The TET policy process serves as a gateway for crucial and sensitive conversations about equity which are connected to personal feelings, bias, and perspective. The interviewees all had differing understandings of what the term equity meant, and they were still able to write a plan addressing their specific equity gaps. District-level administrators are not trained in, nor do they have a window to begin discussions about equity prior to the TET process. School leaders need in-depth, hands-on, and customized training to create more equitable learning environments for all students. While most principal-development programs and quick-hit workshops might touch on diversity, they rarely offer the depth of guidance needed to make a real change ( Zardoya, 2017 ). The TET process uses the equity gap data to start the conversation and guide a goal-oriented or solution-based practice when identifying strategies for economically disadvantaged students to access effective teachers; however, the level of depth regarding equity is not present.

Artifact and Low-Inference Evidence Findings. A third qualitative finding from the artifact and low-inference evidence is anchored into the theme of identifying meaningful root causes. The findings are derived from the most common root cause identified by most of the districts as supporting effective teachers. To get to that point, the districts are required to look at the raw state assessment data and write the equity plan based on percentage point gaps between economically and non-economically disadvantaged students. The trigger of the TET process and plan was a 10%-point gap among students of color or economically disadvantaged sub-populations in comparison to students in the white sub-population. The TET process for using raw data is like that of an Equity Audit where Skrla, et al. (2009) , use a 10% deviation from the district average to ensure greater equity. Upon identifying the percentage gap, the district enters the TET process of identifying where the problems manifest and pinpointing the root cause of the problem.

The root cause analysis guidance requires the districts to correlate the student performance gaps to a gap in access to effective educators by having them choose one of four reasons as to why there is a lack of access to effective educators for economically disadvantaged students who need the most effective teachers ( Skrla, 2009 ). The root cause analysis process is funneled into attracting, assigning, supporting, or retaining effective teachers. Districts within their practice of the TET policy must choose one or many of these root causes to identify strategies that specifically address the equity issue of why economically disadvantaged students do not have access to effective teachers.

11. Discussion

The main characteristic of the TET policy is anchored into the equity framework of access by ensuring that the most marginalized students have access to the most effective teachers ( Skrla et al., 2009 ). The intent of the TET policy is to ensure that the highest needs students are granted access to the most effective teachers as they have the most direct correlation to student learning ( Hattie, 2009 ). The qualitative data indicates that the district-level stakeholders’ definition of an effective teacher is not the same as the TET policy’s definition. The stakeholders each provided an inconsistent definition of an effective teacher that does not align with the definition written into the TET policy. The TET policy defines effective teachers as those who have been in education for more than one year and who are certified in the content area in which they teach ( TET, 2019 ). According to the interviewees, effective teachers are not defined by experience, certification, or in-field placement. The districts do not associate those characteristics with those of an effective teacher. This contradiction of definitions can contribute to the decentralization theory of the TET policy.

Decentralization is a specific form of organizational structure where the top management delegates decision-making responsibilities and daily duties to middle or lower subordinates ( Manna & McGinn, 2013 ). The decentralization of the TET policy is caused by the stakeholders involved during the various levels of plan creation, implementation, and monitoring. While decentralization for the TET policy plan implementation allows principals and teachers to revise and make quick decisions when needed, the lack of consistency and knowledge about the characteristics of an effective teacher can cause barriers to planning implementation.

The rural district-level stakeholders believe that there are no choices for access to effective teachers for economically disadvantaged students due to a lack of applicants, location, and low numbers of both students and teachers. While those may be barriers for rural schools, this thought process can be correlated to the lack of understanding about equity and the key factors or building blocks needed for districts to provide more equitable practices. The building blocks of educational equity needed to close equity gaps include higher-order thinking skills for all students, multiple measures to assess school performance and progress, resource equity, equity strategies, evidence-based interventions, and policy-to-practice sustainability practices ( Cook-Harvey et al., 2016 ). To promote access to effective teachers for economically disadvantaged students, teachers must have an awareness of effective practices that promote student excellence and higher-order thinking skills that do not sacrifice expectations in exchange for compliance ( Hammond, 2015 ).

The rural districts must be aware of the various strategies, understand their specific equity gaps and root causes, and create a plan that is monitored to build capacity in the teachers they currently must promote access to the most effective teachers for their highest needs students’ populations including economically disadvantaged students.

12. Limitations and Recommendations for Policy and Practice

The TET policy is a state-level interpretation of one of the federal initiatives or requirements from the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) statute ( TET, 2019 ). While there are studies and empirical research about various mandates within the ESSA statute as well as around educational equity, there is limited empirical research about the TET policy. The TET policy process is initiated for districts receiving Title I funds requiring the districts to describe how they plan on addressing or improving gaps as they relate to low-income students and students of color being taught at higher rates than other students by inexperienced, out-of-field, and ineffective teachers ( TET, 2019 ). The districts are required to report the closing of student performance gaps via state assessment data, however, there is little to no empirical research about how the TET policy specifically addresses or influences the equity gaps otherwise. This can pose both a limitation and an opportunity for researchers to continue to learn about the TET policy’s influence on equity gaps in Texas. The limitation is the lack of empirical data and research.

The recommendation is to continue to research the policy, both qualitatively and quantitatively based on the decision of the researcher/practitioner to enhance the availability of empirical data regarding the Texas policy response to the equity gap problems for economically disadvantaged students in Title I schools. Future researchers can use qualitative methods to test and validate this research as well as identify new variables and generate new hypotheses regarding their State Education Agency’s Equity Policy Framework. Researchers can also replicate and utilize this qualitative research study of the TET policy for other states centered around additional marginalized student subpopulations resulting in additional empirical qualitative research data.

13. Conclusion

The significance of this qualitative research is to determine how the SEA’s, Texas Equity Toolkit (TET) policy, addresses and/ or influences the equity problem as defined by the Excellent Educators for All (EEA) policy. This research provides an in-depth, qualitative description and analysis of how the TET policy addresses the equity gaps for economically disadvantaged students and influences economically disadvantaged students’ access to effective teachers in rural, Title I, Region 17 districts. Educational equity gaps generally include unequal distribution of resources, including highly qualified or effective teachers, curriculum, and funding disparities for marginalized student populations, unequal access to learning opportunities focused on higher-order thinking skills, multiple measures of equity, and a lack of evidence-based interventions ( Cook-Harvey et al., 2016 ). There are historical attempts to solve the long-standing educational equity problem using state and federal statutes, policies, and mandates that have not resulted in a one-size-fits-all solution.