A Comparison of Clinical Features of Depressed and Non-Depressed People Living with HIV/AIDS, in Nigeria, West Africa ()

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization predicted that by the year 2020, depression will be the leading cause of world wide disability [1]. In September 9, 2005, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) acknowledged that presence of depression in subjects with chronic illness adversely affect the management and outcome of chronic illnesses. The CDC called for public agencies to “incorporate” mental health promotion into chronic disease prevention efforts [2]. Ohaeri and colleague at Ibadan, reported that at least 49% of the patients attending the general outpatients clinic at University College Hospital in Ibadan had a significant number of depressive symptoms, occurring either as the only the symptom or as part of their physical illness [3].

Depression silently destroys families and ruins careers of affected individuals. It is debilitating, progressive, relentless and age’s patients’ prematurely [4]. It is the most prevalent mental disorder among HIV-infected individuals [5] with prevalent rates two to four times higher than those found in the general population [5-7]. It is also key predictors of poor adherence to HIV medication [8,9], and negatively impact on clinical outcomes [10].

There are nine symptoms listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSMIV) [11] for depressive disorder namely, sleep disturbance, interest/pleasure reduction, guilt feelings or thoughts of worthlessness, energy changes/fatigue, concentration/attention impairment, appetite/weight changes, psychomotor disturbances, suicidal thoughts and depressed mood. For diagnosis of major depression, five of the nine must be present for at least two weeks and one of those five must be loss of interest or pleasure or depressed mood [1].

More recent work on the social influences on depression, found a significant correlation between social factors and depression [12]. The concept of social determinants seeks to theoretically and empirically explain how social organization affects health. Economic status or variables related to income or financial status is reported to be significant determinant of depression [13]. The socio demographic factors of age, gender, marital status, education and income are important factors, in explaining the variability in depression prevalence rates. Key North American Studies, particularly the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study [14], the National Commodity Survey [15], the Canadian National population Survey [16] and the Ontario Health Survey [17] found prevalence rates of 2.8% and 3% based on age and gender respectively. Pattern and Colleagues [18] found significant interaction among age, sex, marital status and depression. Prevalence of depression has also been found to vary considerably based on gender [19]. Consistently, women have nearly double or triple prevalence rates than men. Several recent studies confirmed a strong inverse relationship between SES and mental disorder [20]. People in the lowest socio-economic class are more likely to suffer from psychiatric disorder, than those in the highest class [21].

Social Support and Social Cohesion have been identified as playing major roles in the transmission and progression of HIV/AIDS and also depression [22]. While Social support enables people to negotiate life’s crisis, social cohesion helps to stabilize health threatening situations by including and accepting people, and by enableing them to participate freely within the families, the committees and the society [23].

The family APGAR assesses an adult’s perceptions of family support and low scores may indicate parental distress, which will sometimes reflect on parental depression [24]. This empirical measurement allows the development of a family function paradigm that may be likened to the body’s organ system, in that, each component has a unique function yet each is interrelated to the whole.

Finding from psychology autopsy studies have consistently indicated that more than 9 percent of completed suicides in all age groups are associated with psychiatric disorder [4]. It is not the psychiatric disorder itself that increase the risk of completed suicide, but the combination of the psychiatric disorder and a stressor like HIV/ AIDS. Rates of suicide are significantly increased among depressed patients. The association between hopelessness, depression and suicide has been well documented [10]. Hopelessness, being a feeling of despair and extremely pessimism about the future, forms part of PHQ-9 questionnaire of depression. Central to depression are negative thoughts generated by dysfunctional beliefs, which in part may trigger suicidal behaviour in HIV-positive patients.

This study therefore aimed to compare the clinical features of depressed and non-depressed HIV sero-positive subjects with a view to delineate HIV-related depression as a clear clinical entity with treatment implications.

2. Methodology

This study was conducted at the HIV/AIDS clinic of Kwara State Specialist Hospital, Ilorin, North Central Nigeria. Eight hundred patients have been enrolled and over six hundred are on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). The centre is currently being founded by a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), Friends for Global Health.

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study carried out from 1st of March to 30th July, 2013. The inclusion criteria were all consented HIV/AIDS positive respondents, who presented at the Clinic. The exclusion criteria were the critically ill subjects and those who refused to participate.

The sample size was estimated using the Fisher formular [25], using 21.3% from a previous study [26], as the best estimate of depressive disorders among People Living with HIV/AIDS. A minimum size of 218 was calculated using Fisher’s formula but 300 was used to increase the power and reliability of the study. Pretesting was carried out at the Kwara State Civil Service Hospital, using 30 respondents (10% of the sample size).

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Kwara State Ministry of Health before commencement of the study. The respondents were adequately informed about the nature of the study and its benefits. An interviewer administered questionnaire was used. However, for subjects who do not understand English, a local dialect version of the instrument was used.

The Patients Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [27] is a brief, 9-item, patients self-report depression assessment tool that was derived from the interview-based PRIMEMD [28]. It was specifically developed for use, in primary care general medical settings. Many depression screening and severity tools have been used in primary care, with good results. The PHQ-9, however, offers several advantages to other tools. Because the items and the scoring of items on the PHQ-9 are identical to the symptoms and signs of DSM-4 major depression, the tool is easily understood with very high face validity for patients and clinicians in primary care. Many other instruments use a 1-week time frame, but the PHQ-9 uses a 2-week time frame, which conforms to DSM-4 criteria. It is the only tool that was specifically developed for use as a patient self-administered depression diagnostic tool, rather than as a severity or screening tool. It is the only short self-report tool that can reasonably be used both for diagnosis of DSM-4 major depression as well as for tracking of severity of major depression over time [29]. Psychometric evaluation of the PHQ-9 revealed a sensitivity ranging from 62% - 92% and a specificity between 74% - 88% [27-29]. All subjects screened positively for depression using Patients Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ- 2), which was the first two questions of PHQ-9, triggered full diagnostic interviews by the behavioural scientists. Scoring and level of depression was assessed viz: (1 - 4) Minimal depression, (5 - 9) Mild depression, (10 - 14) Moderate depression, (15 - 19) moderately severe depression, and (20 - 27) severe depression. Some direct depression care, such as care support, coordination, case management, and treatment was embarked on. The PHQ- 9 was administered to all the respondents, to screen for depression, until the estimated sample size of 300 was obtained. Respondents who scored one and more were assessed clinically for depression.

Responses to question 9, “Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or hurting yourself in some way.” Any affirmative response to question 9, or a PHQ-9 score of >9, required a suicide risk assessment within 24 hours.

The three keys of social determinants of depression (SDS) were assessed and the association with depression sought. Based on existing research [30-32], we used three key SDH: socioeconomic status, social cohesion and negative life events (Appendix B). Socioeconomic status included two indicators: years of schooling and self-reported economic status of the family, in general, in the previous year. Categories for years of schooling were as follows: above average (7 years and above), average

(1 - 6 years) and below average (0 year). Economic status of the family was self-reported as good, average or poor. Social cohesion was assessed from responses to two questions: 1) In the previous year, how often did you ask someone for help when you had problems? (Never = 1; Seldom = 2; Sometimes = 3; Often = 4), and when you had problems? (spouse or lover; parents, brothers, sisters or children; other relatives; people outside the family; organization or schools with whom you are affiliated; government, party or trade unions; religious or non-governmental organizations; other organizations) (No = 0; Yes = 1). Negative life events were assessed using a 12- item scale (serious illness in oneself, serious illness in the family, financial difficulties, conflict with spouse, conflict with other family members, conflict with people in the village, conflict between family members, infertility issues, problems at work or school, problems in an intimate relationship, abuse and other events) [33]. For each life event that occurred in the last year, or that occurred earlier but continued to have a psychological effect during the past 12 months, the respondents indicated when the life event occurred, its effect (positive or negative) and the length of time over the last year that the psychological effect lasted. We used the sum of the number of life events with a negative effect as a measure of negative life events.

Age, gender, marital status, education level, self-rated financial status, social support and social cohesion, employment status and estimated monthly income were the socio-demographic variables and potential confounders. Marital status as well as educational level was assessed. Occupation was grouped into traders, civil servants, self employed, unemployed and students. Monthly income was assessed using the minimum wage stipulated by the Federal Government of Nigeria, which was put approximately at Twenty Thousand Naira (N20,000) equivalent to ($125) US dollars.

The Family APGAR questionnaire [33,34] was used to determine the prevalence of self-reported family dysfunction present in the respondent (Appendix B).

Completed questionnaire and measurements were entered into a computer data base. The data were analyzed using the epidemiological information (Epi-info) 2005 software package of Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The 2 by 2 contingency tables were used to carry out Chi-square test and to find out the level of significance and values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

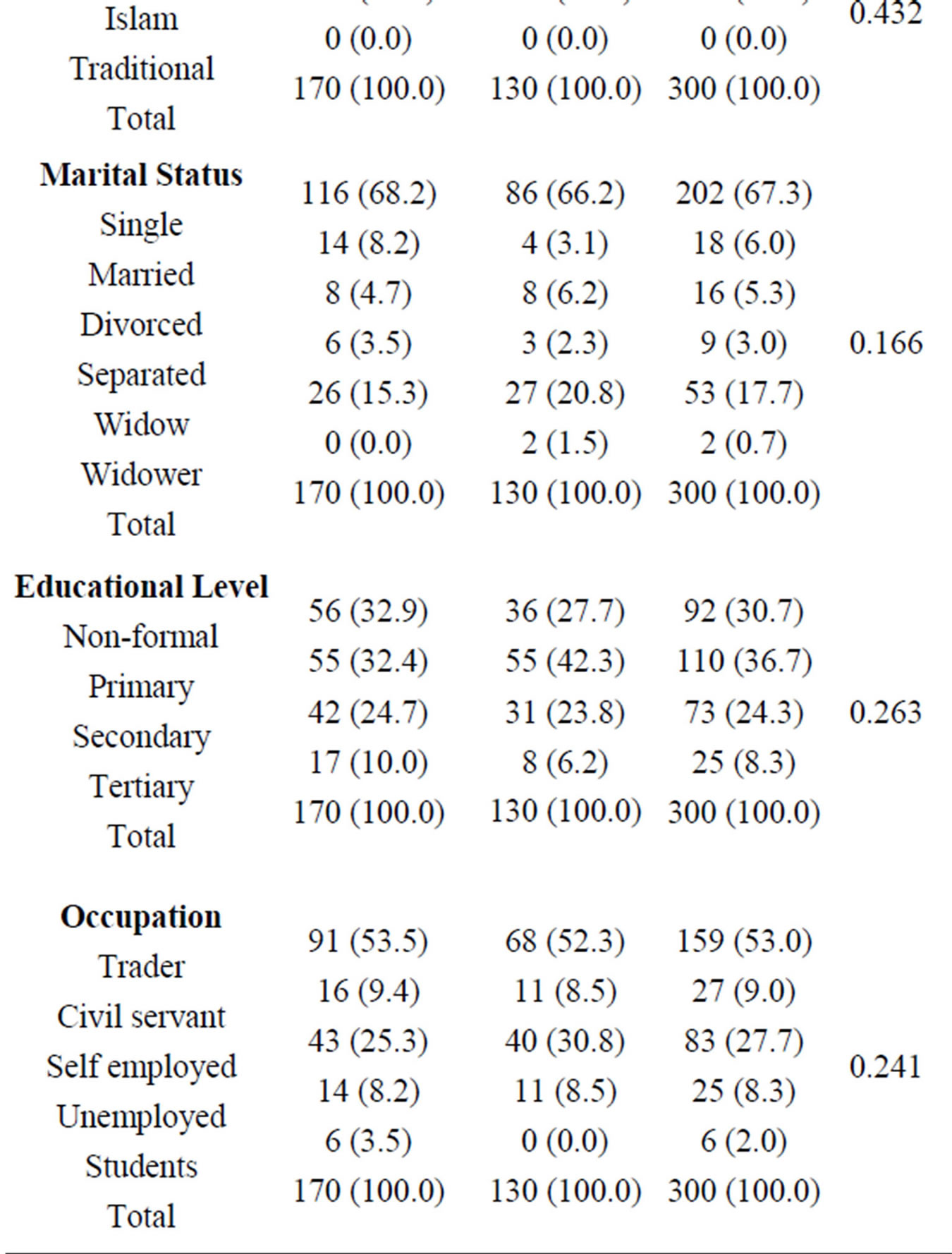

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic profile of the respondents. One hundred and seventy (56.7%) of the respondents met the study criteria for depression, while

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of depressed and non depressed HIV positive patient.

130 (43.3%) did not. Depression was prominent among age group 36 - 40 years and least among those above 60 years of age. There was female preponderance 139 (81.8%). Majority of depressed subjects were single 116 (68.2%). The non-depressed were comparatively more married. Most of the subjects did not go beyond primary education. More unemployed 14 (8.2%) subjects were found among the depressed. Moreover, more depressed respondents had no source of income than the non-depressed.

Figure 1 shows that while 130 (43.3%) of the respondents were not depressed, 170 (56.7%) satisfied the criteria for a depressive disorder using the PH-9. Among the respondents, 109 (36.3%) had minimal depression, while 4 (13%) were severely depressed.

Table 2 shows that social cohesion was lower in depressed 133 (78.2%) than non-depressed 102 (78.3%), so also was poor economic status 62 (36.5%). Moreover, depressed patients had more stressful life events 54 (31.8%) than the non-depressed, 20 (15.4%). Most of the depressed had below average year of schooling 80 (47.0%) are opposed to 55 (42.3%) for the non-depressed. These parameters were statistically significant.

Table 3 shows that depressed patients had severely dysfunctional family 75 (44.1%) than the non-depressed 67 (51.5).

Table 4 shows the assessment of suicidal assessment. Non-depressed HIV positive patient did not have the feeling of hopelessness 0 (0.0%) neither do they have taught of taking life 9 (0.0%) nor plan to take life 0 (0.0%). This is opposed to the depressed who had 29 (17.1%) feeling of hopelessness, 28 (16.5%) and 6 (3.5%) plan to take life. This is of statistical importance.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of depressive disorders among HIV/ AIDS patients attending the lentiviral clinic, of the Kwara State Specialist Hospital Sobi, was 56.7%. Depressive symptomatology in the study population, mirrored the presentation of depression in other settings. It falls within the prevalence rates seen internationally [33-37]. The prevalence of depression obtained from this study also agrees with most local studies [38,39]. In this study, one

Figure 1. Levels of depression among the respondents, using the patients’ health questionnaires (PHQ-9) scale.

Table 2. Social determinants of depression between depressed and non-depressed HIV patients.

Table 3. Association between family APGAR and depression among sero-positive HIV patients.

Table 4. Suicidal ideation between depressed and non-depressed HIV positive subjects.

hundred and thirty (43.3%) of the respondents were not depressed. On the contrary using the same PHQ-9 rating Bongongo and Colleagues [40] reported out that 43% of the respondents were depressed, while 57% were not.

Depression was prominent among age group 36 - 40 years and least among those above 60 years of age. Compared to depressed patients, non-depressed patients were younger. This was similar to the finding of Rajdeep and colleagues [41]. The difference seen clinically may be due to the fact that the older HIV positive patients had gone through numerous stressful life events. The older people are, the more stressful life events they experience and hence, more likelihood of being depressed.

There was female preponderance 139 (81.8%). More female were more depressed. Women (68.7%) reported significant higher prevalence of depression than men (32.3%) in the study of Averina and Colleagues, in Russia [42]. The above findings, is in consonant to our study. On the contrary, a South-African study [43] found the prevalence rate of depressive symptomatology to be almost equal in both sexes.

There were significant statistical correlation between marital status and depression. In this study majority of depressed subjects were single 116 (68.2%). Previous studies have reported marriage as being protective against depression; and that being single, divorced, and widowed is associated with depression and suicide risk [44]. Many of our HIV positive patients had lost a partner to HIV/AIDS and the majority had no partners, hence depressed patients were more likely to be widowed. Bogongo and colleagues [40] reported that 24.4% of nondepressive subjects were single, as opposed to 75.6% of depressed respondents.

In this study 20 (11.8%) had no source of income as compared to 11 (8.5%) of non-depressed. Income had consistently been identified as important factors in explaining the variability in the prevalence of depression. Key North American studies, particularly the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study [14], the National Co morbidity Survey [15], the Canadian Health Population Health Survey [16] pointed out this fact. Similarly, economic status or variables related to income or financial status were reported to be significant in Hong Kong [45] and Beijing [46]. Less favourable financial status and lower incomes are common correlates of more depression [42]. The socio economic status was poor 62 (36.5%) among the depressed, as opposed to the non-depressed 41 (31.5%). This was similar to the finding of Unnikrishnan in Coastal South India, who reported that, 58 (65.2%) depressed subjects had poor socio economic status, while 31 (34.8%) did not [47].

Social cohesion was low in depressed 133 (78.2%) than non-depressed 102 (78.3%). This was similar to findings of Unnikrishnan [47], who reported social isolation in 115 (84%) of the respondents. O’Sullivan [48], while studying the psychosocial determinants of depression found social factors as a risk factor for depression. Social support and good social relationship makes an important contribution to health and prevent the depression. Social support also helps to give people the emotional and practical resources they need. Belonging to a social network of communication and mutual obligatory makes people feel cared for, loved, esteemed and valued. This has a powerful protective effect on health. Therefore, good social relationship can reduce depression. On the other hand, low social support causes more stress and can accelerate or worsen the progression from HIV to AIDS [49]. Therefore social programmes should be developed to facilitate stronger social networks for them. Social networks of the subject may shrink owing to loss of loved ones and significant others such as spouses, friends, or peers. For widows or widowers, the loss of their life companions (usually also their confidant) could be devastating.

Depressed patients had more stressful life events 54 (31.8%) than the non-depressed, 20 (15.4%). This is in consonant with the findings of Onya and co-workers [50], who reported that 108 (72%) depressed respondents had stressful life events, while 42 (28%) non-depressed did not.

Depressed patients had severely dysfunctional family 75 (44.1%) than the non-depressed 67 (51.5%). The family as a group is supposed to generate, tolerate or connect health issues within its membership. Whatever happens to one member of the family has some effects upon the family collectively and requires a whole sense of accommodation on the part of the other family members. From the foregoing, it is clear that most of the depressed HIV/AIDS patients, had dysfunctional families hence deviated from the Stevenson’s family [51] developmental model, which views family tasks, as sustaining appropriate health patterns and providing mutual support and acculturation of family members. The family tasks of satisfying the biological, cultural and personal needs and aspiration were not met. Furthermore, the needs of the patients, according to Maslow’s hierarchy [52], were far from being satisfied. This included the physical needs, safety needs, need for love and belonging, the needs for esteem and finally the need for self-actualization.

Non-depressed HIV positive subjects did not have the feeling of hopelessness 0 (0.0%) neither do they have taught of taking life 9 (0.0%) nor plan to take life 0 (0.0%). This is opposed to the depressed who had 29 (17.1%) feeling of hopelessness, 28 (16.5%) and 6 (3.5%) plan to take life. This is of statistical importance. Hopelessness is a primary mediator that links depression and suicidal ideation, and the more hopeless the individual feels about the future, the more depressed they are likely to become, unless appropriate interventions are implemented. The strongest predictor of suicide is psychiatric illness [53]. Over 90 percent of persons who commit suicide have diagnosable psychiatric illnesses at the time of death, usually depression [53].

5. Conclusions

Depression is common among the female, single, unemployed, with below average year of schooling. The socioeconomic status was poor among the depressed compared to the non-depressed. Social cohesion was low in depressed than non-depressed. Moreover, depressed patients had more stressful life events as well as severely dysfunctional family. They are more prone to feeling of hopelessness, taught of taking life and plan to take life.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms among People Living with HIV/AIDS is significant, underscoring the need for increased attention to the psychological wellbeing of this group to alleviate their suffering as well as to minimize the impact of depression on their life.

Appendix A

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [27-29].

Scoring

1 - 4 Minimal depression

5 - 9 Mild depression

10 - 14 Moderate depression

15 - 19 Moderately severe depression

20 - 27 Severe depression

Appendix B

The Variables of Social Determinants of Health [30- 32]

Self reported economic status of family

Poor

Average

Good

YEARS OF SCHOOLING

Below average (0 year)

Average 1 - 6 years

Above average 7 years and above

SOCIAL COHESION

Low 1 - 2 points

Fair 3 - 5 points

High 6 - 9 points

Negative life events

>3

2

1

0

Appendix C

Assessment of Family Function [33,34].

Scoring

0- 3 Severely dysfunctional family

Severely dysfunctional family

4- 6 Moderate dysfunctional family

Moderate dysfunctional family

7- 10 Highly functional family

Highly functional family

NOTES