Long-Term Effect of Photoperiod, Temperature and Feeding Regimes on the Respiration Rates of Antarctic Krill (Euphausia superba) ()

1. Introduction

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba (hereafter krill), is a dominant pelagic species in the Southern Ocean and has significant economic and ecological importance [1-4]. Their overall prosperity and high biomass in the Southern Ocean is due to their ability to adapt to large seasonal changes in their environment; mainly sea-ice extent, food availability and light intensity and duration [5]. Currently, there are various theories on the overwintering strategies of krill [5]. The reduced primary productivity in the ocean, for up to eight months of the year, requires krill to adopt a range of strategies to survive and avoid periods of starvation [5-8]. Such strategies include overall body shrinkage and protein catabolism [9,10], utilization of lipid reserves [5,7,11-13], switching to a more omnivorous [14-16] and/or carnivorous [8,17,18] diet, as well as feeding on ice-algae [19,20] and sea-floor detritus [21], and suppression of metabolism [5,21,22].

Respiration rates of krill have been extensively studied in the past [5,18,21,23-32], but understanding the physiological responses of krill to a changing environment is scarce. A major question whether the observed decrease in metabolism in winter is caused simply by reduced food availability. Other important influential environmental factors may include photoperiod, temperature, or more complicated, an endogenous annual rhythm that is affected by a strong seasonal cue in the Southern Ocean.

Reduced metabolic rate and feeding activity are suggested to be the most effective energy-saving mechanisms for adult krill during the less productive months [5]. Nevertheless, Huntley et al. [17] suggests that starvation, body shrinkage and reduced metabolism are not common for krill in winter given they found winter krill feeding carnivorously and excreting at summer rates. This contrasts with Atkinson et al. [18] who demonstrated that respiration and clearance rates of juvenile and adult krill during autumn were only one-third of summer rates, which even failed to increase after 11 days of abundant food. Whereas, during the summer season of the same study, Atkinson and Snÿder [33] concluded that the metabolic and feeding activity of krill did respond positively to periods of high food concentrations. Irrespective of feeding conditions, Teschke et al. [32] revealed for the first time that the environmental light regime triggers the changes in metabolic rates of krill, suggesting the Antarctic light cycle is possibly the most important effect on the physiological parameters of krill. Hirano et al. [34] and Brown et al. [35] also suggested importance of light regime in governing maturation cycle of krill.

One of the main characteristics of the Southern Ocean is that water temperatures remain within a narrow range, with an annual variation rarely exceeding 5˚C [36]. An increase in temperature increases growth rate and metabolic activity in crustaceans [37]. Studies by McWhinnie and Marciniak [38], Rakusa-Suszczewski and Opalinski [23] and Segawa et al. [24] all conclude that respiration rate increased with increasing temperature for krill. However, to date, no study has examined the effects of this narrow temperature range on krill physiology within the context of other environmental factors varying over a long-term.

A series of recent work collectively suggest that an endogenous circannual timing mechanism is operating in krill controlling their physiology and behaviour, and that photoperiod is probably acting as the main Zeitgeber [39]. Information on respiration rates over a long period spanning a complete maturity cycle is therefore desired for a greater understanding of the drivers of seasonal patterns of krill metabolism.

In the present investigation, a long-term controlled experiment was conducted in the laboratory using krill that were incubated under different light, food and temperature regimes. The objectives were to test, and to determine, which of these key environmental factors dictate krill respiration rates between the critical period of maturation in late winter/early spring and sexual regression in late summer/early autumn.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Krill

Live Antarctic krill were collected on 7th February 2005 (66˚15'S, 74˚45'E) and 3rd March 2006 (66˚02'S, 79˚32'E) using a rectangular mid-water trawl net (RMT 8) [40] on board the RSV Aurora Australis. The water temperature during krill capture was −1˚C. Krill were transferred into 200 - L tanks and maintained with a continuous supply of seawater in a cold laboratory (0˚C, dim light and no food) on board the ship. Once north of the Polar Front, the continuous water supply was cut off and 50% of the tank water was exchanged with freshly pre-chilled seawater each day.

2.2. Aquaria Conditions

On return to the research aquarium at the Australian Antarctic Division in Kingston, Tasmania, krill were acclimated to the aquarium conditions [41]. Krill were maintained under light conditions that were adjusted throughout the experimental period to mimic the natural Antarctic seasonal light cycle. Lighting was provided by twin fluorescent tubes. A personal computer controlled-timer system was used to set a natural photoperiod corresponding to that for the Southern Ocean (66˚S at 30 m depth). Continuous light and a maximum of 100 lux light intensity at the surface of the tank (assuming 1% light penetration to 30 m depth) during summer midday (December), a sinusoidal annual cycle with monthly variations of photoperiod and daily variation of light intensity was calculated. At the start of each month, a new photoperiod was simulated by adjusting the timer system [42].

Krill were kept in eight different experimental conditions (natural light cycle or complete darkness, fed or starved conditions and temperatures ranging between −1˚C and 3˚C), as outlined in Table 1. Density of krill in each of the tanks was 0.5 - 2 inds/L. Overall krill mortality in the system is approximately 0.1% of the population per day. An algae mixture of the cultured pennate diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, and the flagellates Pavlova sp. and Isochrysis sp., and diatom Thalassiosira sp., which are concentrated bulk feeds of instant algae mixed with seawater (Reed Mariculture, California), and minced clam meat were fed at various regimes summarised in Table 1.

Due to operational reasons (large size of tanks and space constraints) experimental tanks were not replicated to account for “tank effects”.

Table 1. Summary of the experimental conditions.

2.3. Measurement of Respiration Rates

Respiration measurements were conducted in filtered seawater (0.1µm pore size). From each of the experimental tanks, four random krill were selected and incubated individually in 1.2 - L glass reagent bottles filled with filtered seawater at the various time points. Krill were rinsed with filtered water that was acclimated to the correct temperature and added to the bottle. Two controls of the same volume without krill were also taken for each experimental treatment. The krill and control bottles were incubated for 24 hours. At the end of the incubation period, oxygen concentrations were measured after immediate fixing for Winkler titrations, as described in Omori and Ikeda [43] and Meyer et al. [44] by the use of a titrator; 716 DMS Titrino (METROHM). The total length (TL) of krill was measured (Standard Length 1) and the dry weight (DW) was calculated using the following empirical Equation:

while an alternative Equation is

[45]

[45]

For the sample of TL in this study, the correlation between predicted DW for these two equations was 0.999 and the average ratio, DW2/DW1, was 1.16 with a range of 1.06 to 1.17.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data was analysed using the GenStat package [46] to provide an ANOVA for each dataset and for the corresponding treatment applied in each. Initially, the TL was also included as a covariate in each ANOVA. A trend analysis with month was also determined by using a decomposition of the month factor sums of squares into linear and quadratic orthogonal polynomial components with the remainder degrees of freedom used to obtain a lack-of-fit statistic. To do this, a continuous version of the month factor was created as a variable using integers 1 (August) through to 9 (April), even though for each treatment only some of these months were measured. For the temperature treatment a similar orthogonal polynomial decomposition was applied, but restricted to linear and lack-of-fit terms since there were only three temperature levels tested. Residual plots and histograms combined with normal quantile-quantile plots for each variable were used to examine whether or not the assumptions of homogeneous variance and normal distribution for the residuals were reasonable.

3. Results

Respiration rates were not significantly different (P > 0.05) between the randomly selected males and females at each of the measured time points so the data was combined for sex in all experimental conditions. There was a significant and strong increasing trend with month, which showed an increase in respiration rate from winter to summer in all experimental treatments (Figures 1-3). Mean respiration rates for krill on a DW basis in the treatments natural light versus complete darkness were 0.22 and 0.35 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1, respectively, in August (Figure 1) and gradually increased to December (0.46 and 0.56 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1, respectively). Mean respiration rates for krill in the treatments fed versus starved in August ranged between 0.25 - 0.26 μL O2 mg∙ DW−1∙hr−1 (Figure 2), showing a gradual increase into summer. Krill in Tank A (phytoplankton plus clam) reached mean maximal rates in December (0.51 μL O2

Figure 1. Mean respiration rates on a dry weight (DW) basis (μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1) for the photoperiod treatment (natural light versus complete darkness). The Standard Error of Difference bar (s.e.d) is based on the residual mean square (m.s.) given in Table 2 and the sample of four krill in each treatment by month combination and gives the standard error of the pairwise differences in means for a given month. Any differences that are more than twice the length of the s.e.d. bar based on a t-statistic of 2.0 can be considered significant at the 95% level.

Figure 2. Mean respiration rates on a dry weight (DW) basis (μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1) for the feeding regime treatment (fed versus starved krill). The Standard Error of Difference bar (s.e.d) is based on the residual mean square (m.s.) given in Table 2 and the sample of four krill in each treatment by month combination and gives the standard error of the pairwise differences in means for a given month. Any differences that are more than twice the length of the s.e.d. bar based on a t-statistic of 2.0 can be considered significant at the 95% level.

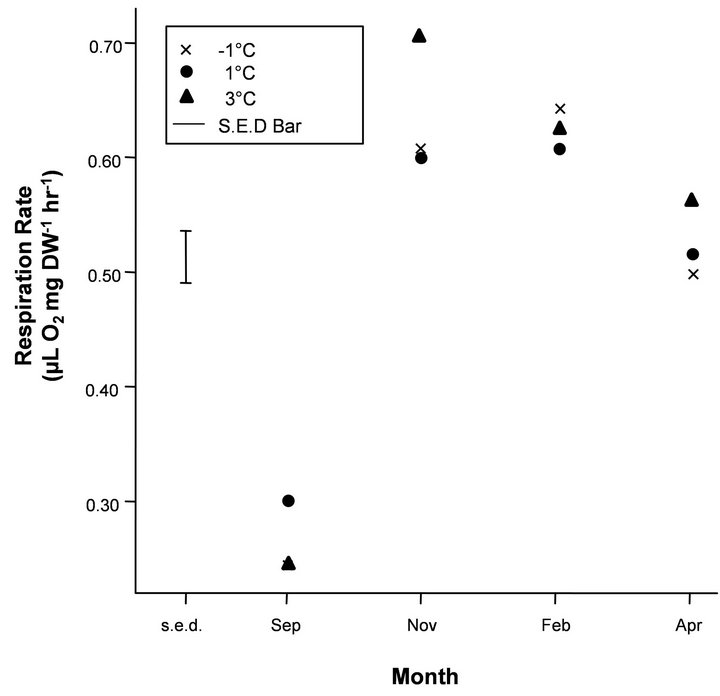

Figure 3. Mean respiration rates on a dry weight (DW) basis (μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1) for the temperature treatment (−1˚C, 1˚C and 3˚C). The Standard Error of Difference bar (s.e.d) is based on the residual mean square (m.s.) given in Table 2 and the sample of four krill in each treatment by month combination and gives the standard error of the pairwise differences in means for a given month. Any differences that are more than twice the length of the s.e.d. bar based on a t-statistic of 2.0 can be considered significant at the 95% level.

Table 2. ANOVA table for each of the experimental treatments with the linear and quadratic orthogonal polynomial decomposition. The covariate total length (TL) was nonsignificant and therefore not included in this table.

mg∙DW−1∙hr−1), with similar rates measured at the end of the experiment in March. Krill in Tank B (phytoplankton only) reached mean maximal respiration rates in October (0.51 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1), and the mean respiration was stabilised at approximately these rates throughout summer until March. Krill in Tank C (starved), however, reached maximal respiration rates in October (0.53 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1), which then decreased in December and March (0.39 and 0.43 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1, respectively). Under natural photoperiod, mean respiration rates of krill under varying temperature regimes (−1˚C, 1˚C and 3˚C) increased from September (means ranging between 0.24 - 0.30 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1) to reach mean maximal rates in November and February (0.60 - 0.71 μL O2 mg∙ DW−1∙hr−1), before a slight decrease in April (0.50 - 0.57 μL O2 mg∙DW−1∙hr−1), under constant food conditions (Figure 3).

The covariate TL was non-significant and there was no significant interaction of treatments with the above trend of month. Residual plots and histograms combined with normal quantile-quantile plots (graphs not shown) showed that the assumptions of homogeneous variance and normal distribution for the residuals were reasonable for each dataset. The mean respiration rates were lower in the natural light treatment compared to complete darkness, and the same trend with month was evident for both treatments (Figure 1). This was determined from the ANOVA since a significant interaction between treatments in this trend was not detected. However, the main effect of treatment was significant (P < 0.01) (Table 2), as expressed in the lower respiration rates for the natural light regime (Figure 1). The corresponding mean difference detected by the main effect term (i.e. averaged over months) was 0.097 with SE of 0.023.

For the food treatments, despite the general increasing trend in respiration rate with month for all treatments (significant “lin” and “quad” terms in Table 2, Figure 2), there was a somewhat strange result for the food treatments in October, which showed respiration rates for animals fed with phytoplankton and clam were significantly lower than those krill fed with phytoplankton only and the starved treatment (Figure 2). This caused the trend analysis (lin + quad) to have a significant lack-offit (“Deviations” terms in Table 2) for both the month main effects and month by treatment interaction.

There was a general increasing trend in respiration rate with month for all temperature treatments, but no significant interaction with treatment or main effect of treatment (Table 2). The significant lack-of-fit term (i.e. “Deviations”) for the month decomposition for the temperature treatment is due to the very sharp increase in respiration rate between September and November, which is difficult to model using a 2nd degree polynomial. The “Dev.Lin” term in the decomposition of the month by treatment interaction represents the difference in the linear trend with temperature of each month’s deviations from the fitted 2nd degree polynomial and is only just significant at the 5% probability level. This is due to the reversal of the order of treatments with respect to respiration rate for September for which the 1˚C regime gave the highest rate which was not the case for the other months. However, considering the length of the S.E.D bar in Figure 3 relative to the differences between temperatures for each month considered separately indicates a lack of statistical significance and combined with this, the marginally significant “Dev.Lin” term, makes any strong inferences drawn from the significance of this term unjustified.

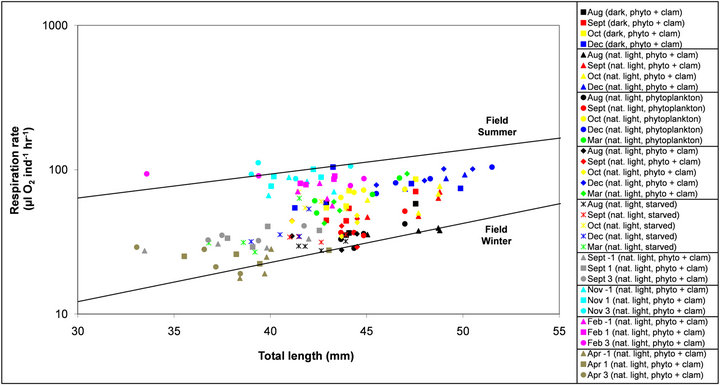

Individual respiration rates, as a function of total length, were compared to a field based study by Quetin and Ross [5] (Figure 4). Laboratory data from this study was generally observed to fall between Quetin and Ross’ winter (July −1.5˚C—not feeding) and summer (January 2˚C—feeding) trend lines, which represented the relationship between total length and oxygen consumption from the wild in Bransfield Strait [5].

When the dry weight equation giving DW2 was applied in place of DW1 the differences in results to those reported in Table 2 were very minor and therefore did not have any effect on the interpretation or conclusions derived from the reported results.

4. Discussion

There was a strong trend of respiration rate with month, with respiration increasing from late winter/early spring to late summer/early autumn, during the important and energy consuming maturation and regression process of krill, under all experimental conditions; natural Antarctic light cycle versus complete darkness, fed versus starved krill and krill subjected to different temperature regimes (−1˚C, 1˚C and 3˚C). The covariate total length of krill was found to be non-significant and there was no significant interaction of experimental treatment with month or main effect of each treatment. However, the power to detect a difference was low, due to the low sample number of four krill in each month and treatment. Due to experimental design it was not possible to examine any interaction among the three possible environmental parameters. Nevertheless, although the power to detect a difference was low the results from this study suggest that the three experimental parameters (light, food and temperature) were not the primary factors directly driving the overall seasonal pattern of respiration rates that have been observed through the experiment between September and April.

Figure 4. Laboratory and field measurements of respiration rates (µL O2 ind−1∙hr−1, on a logarithmic scale) of Antarctic krill as a function of total length (mm). The two trend lines are an approximate representation of Quetin and Ross (1991) field respiration measurements in the summer (January 2˚C) and winter (July −1.5˚C) at Bransfield Strait for krill between 30 and 55mm in length. Laboratory measurements are represented by the coloured symbols at various time points (combined sex) and experimental conditions (natural light versus complete darkness, fed versus starved krill and temperatures between −1˚C and 3˚C). Refer to Table 1 for details on experimental conditions.

Below we discuss the potential candidate mechanisms that could be related to seasonal changes in metabolism.

4.1. Food Availability

Recruitment and population size of krill are strongly influenced and dictated by the survival success during the dark and less productive winter [5,18,47,48] Krill undertake a variety of strategies to avoid starvation during the season of reduced primary productivity. Krill are known to exploit many types of food resources in the wild so the chances they will actually encounter overall food shortages may be small [49]. Krill almost certainly exploit whatever particulate matter is in the water column including elements of the microbial loop and marine snow [50], as well as ice-algae [19,20] and sea-floor detritus [21,51]. Heterotrophic feeding on protozoans [52] and copepods [8,17,18] are also reported. Lowering overall feeding activity and metabolism are also suggested as overwintering strategies [5,18, 21,22,39,53]. It is difficult to recognize and interpret whether metabolic rates are the result of changes in feeding activity, or vice versa, feeding activity is reflected by the changes in metabolic rates [32]. According to Ikeda and Dixon [29], an increase in metabolic activity in krill was reported to follow the ingestion of food.

Quetin and Ross [5] showed that oxygen consumption in a large size range of adult krill from Bransfield Strait was 33% higher in a summer experimental setup (January, 2˚C) compared to winter (July, −1.5˚C). They suggested that adult krill do not feed in winter, and have considerably lowered metabolic rates and negative or zero growth rates. Meyer et al. [53], through examining size and colour of digestive gland, suggested that krill had either not been feeding or had ingested a heterotrophic and autotrophic diet at low rates during winter. Huntley et al. [17] examined krill west of the Antarctic Peninsula during winter (July-August) and the preceding summer (December-January) in a region similar to that of Quetin and Ross [5]. Huntley et al. [17] demonstrated that krill fed on a carnivorous diet during winter, particularly copepods, which enabled them to sustain growth comparable to that of summer. They further suggested that starvation, body shrinkage and reduced metabolism is not common for krill during winter, but instead, carnivory is sufficient for growth and to meet energy requirements until phytoplankton blooms occur in spring.

Under constant food supply in this study, krill were observed to be feeding year round. The digestive glands were dark green and healthy looking during the experiment (personal observations), indicating that krill were continuously feeding [54-56]. Total lipid and fatty acid content and composition analysis of the digestive gland and the whole body of krill (Brown et al. unpublished)

also showed that krill were actively feeding year round.

Our results may help interpret respiration rates reported in winter krill by Quetin and Ross [5]. Despite constant year round feeding, a reduction in respiration rates was observed in the current study in all experimenttal krill during the non-summer months on a dry weight basis. Respiration rates also increased in krill with month in both fed and starved krill.

At an individual level, the recorded respiration from krill in the laboratory was distributed fully within the whole range of those measured from summer (feeding) and winter (non-feeding) field experiments by Quetin and Ross [5], as shown in Figure 4. This demonstrated the fact that respiration rates of well fed krill under simulated winter conditions were similar to those nonfeeding winter observations from the field. These krill in Bransfield Strait, despite the fact there may be limited sea-ice, may in fact be feeding to some extent and not starving as it has been suggested [5]. Their conclusions came about from observing that both the faecal pellet production and ingestion of phytoplankton in winter were less than 3% of summer rates, suggesting that adult krill did not derive a large proportion of their energy from carnivory. From our observations, we conclude that when food density is low, krill tend to retain their gut content and do not excrete at the same rate as when they are fully fed, which could have also been the case in wild krill from Quetin and Ross [5].

Reasons for why rates under starvation are maximal in October but not at anytime where values are minimal or medium (Figure 2) remains unsolved. This somewhat contradicts our current general understanding. However, October is the month when krill is becoming meta-bolically active due to its rapid maturation and ovary development therefore maturation process could be the reason behind, and warrants further detailed study in order to confirm this deviation from the general trend in October.

4.2. Temperature

Krill is considered to be stenothermal and is sensitive to slight changes in temperature and other environmental changes [57]. Temperature has been shown to influence the frequency of moulting in krill, and thus overall growth rates, which can vary considerably, even within a narrow annual temperature range that is observed in the Southern Ocean [23,24,38,58,59,60]. McWhinnie and Marciniak [38], Rakusa-Suszczewski and Opalinski [23] and Segawa et al. [24] have also suggested that temperature is a key environmental factor influencing the metabolism of krill, with increasing respiration rates with increasing temperature (0˚C to 5˚C, −1˚C to 2.4˚C, and −1.5˚C to 5˚C, respectively). This is generally true up to 5˚C, but above this temperature, krill are probably thermally stressed [59,61]. This relationship between temperature and respiration has been reported for another euphausiid species. Respiration rates in Thysanoessa longipes in the Japan Sea increased exponentially with an increase of temperature from 0˚C to 8˚C [62].

In our study, however, there was no significant interacttion with the temperature treatments (−1˚C to 3˚C) and month or main effect of temperature, indicating that temperature was not a key environmental variable to cue changes in seasonal metabolic activity.

4.3. Photoperiod

Light intensity and duration has strong seasonality in the Southern Ocean, from near-constant light in December to near-constant darkness in June. Photoperiod has been suggested as the likely trigger and possibly has the most important effect on the changes in metabolic activity of krill [32]. The respiration of krill in the starved and fed treatments, as well as krill in the various temperature regimes in our study, increased with month during the stages of maturation and sexual regression under a natural light period. These results may suggest that photoperiod also has a significant influence on krill metabolic rates. However, the respiration rates of krill were higher in the complete darkness compared to a natural light treatment, with the same increasing trend with month. There was no significant interaction between treatments, but when all data was pooled to increase the power of the test, the main effect of treatment was significantly different (P < 0.01). These results oppose those by Teschke et al. [32] who reported a significant decrease in respiretion rates in krill incubated under complete darkness compared to light. Experimental conditions were different between these studies, with a tank size of 100 - L used by Teschke et al. [32], and 1670 - L in the present study. A larger tank may have facilitated an increase in swimming activity inducing higher respiration rates in this study. The fact that maximum respiration rates were recorded under darkness in our study could correspond to a higher swimming activity in darkness, and the larger size tank in our experiment compared to Teschke et al. [32] allowing active swimming leading to higher respiretion in the darkness. Additionally, the abrupt changes in the light regime, and also variation in timing and duration of the experiments in Teschke et al. [32], may account for the differences observed. Our study was a closer emulation of “natural” conditions in the wild compared to those of Teschke et al. [32] which may have influences these results.

4.4. Endogenous Annual Rhythm

Endogenous circadian timing system in Antarctic krill and its likely link to metabolic key processes has recently been reported and these may not only be critical for synchronization to the solar day but also for the control of seasonal events [63]. There are increasing number of studies suggesting adult krill entering a state of winter quiescence in the wild [18,53]. There is evidence on the one hand of continuous feeding throughout the year [17] and, on the other, of reduced respiration and lack of response to food increase [18]. The different conditions experienced by sampled populations undoubtedly underlie these contrasting observations. Published winter based respiration measurements from the field [5,17,21] and long-term controlled experiments in the laboratory (this study), were conducted during the late winter/early spring months so the seasonal timings of krill were in a winter state and comparable. Therefore, reductions in respiration levels were irrespective of effects of photoperiod and feeding conditions within the length of experimental period in this study. The general increasing respiration rates observed from winter to summer in this study, even in starved krill and those kept in complete darkness, were possibly caused by krill changing endogenously to a summer state. This idea of a seasonal endogenous pattern is also evident from the growth and maturation results in Brown et al. [59]. A clear seasonal cycle of growth and maturation for both males and females in the three temperature treatments (−1˚C, 1˚C and 3˚C) were observed under constant and high food concentrations. This is also in agreement with Thomas and Ikeda [64] who showed female krill underwent a regression of external sexual characteristics after spawning, which was accompanied by negative growth and an increase in intermoult period, in both starved and fed krill.

Many biological cycles operate through a combination of endogenous cycles and external environmental cues. If devoid of any external stimuli, free-running endogenous cycles eventually become unsynchronised from the ideal cycle since the mechanism that provide the periodicity are often imperfect [65]. A coordinating cue, or zeitgeber, is required to resynchronise the endogenous cycle. For example, it is believed that Northern krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica) receive a zeitgeber from the dawn sun immediately prior to their descent to depths that are devoid of any further light cues [66]. Antarctic krill reproduction has successfully been initiated by providing continuous light after prolonged darkness in the aquarium [34]. Further, receiving a cue of darkness or accelerated shortening of day light at the timing of their maturity regression period has been demonstrated to play important role in adjusting their seasonal maturation cycle to the environment [35]. Although the results from our study indicate that the three experimental parameters (light, food and temperature) were not directly involved in dictating general overall pattern of respiration rate of krill, the general seasonal pattern in respiration rate could be result of a free running endogenous annual cycle. This pattern could have been synchronised to the seasonal light regime in the aquarium [42] prior to start of the experiment, but could not be changed due to constant darkness or constant food supply during the experiment [64,67].

5. Conclusion

Krill use a variety of strategies to survive the less productive winter, which highlights the fact that krill is a versatile species and is a contributing explanation for its high biomass in the Southern Ocean [68]. It has been widely accepted that a reduction in metabolic activity can occur during winter, with varying environmental variables considered to be responsible, which can differ between different regions of the Southern Ocean. Under controlled conditions, this long-term study has shown that the environmental variables; light, food availability and temperature, may not necessarily be the major factors in governing the metabolic cycles as general pattern of winter low summer high was observed in all treatments in this study. It is suspected that an endogenous rhythm was operating in krill [64,67], controlling overall general seasonal pattern of metabolic activity [39]. The significance of an “internal clock” mechanism is still relatively unknown and warrants further investigation, particularly examining photoperiod as the possible cue for dictating internal processes [35,39,63,64,67]. Future experiments will need to incorporate measurements over a whole cycle (over one year) with some overlaps to determine when an observed respiration cycle starts to become unsynchronised from the ideal annual pattern.

6. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the captain and crew of RSV Aurora Australis for their skilful assistance during the collection of krill. We also extend our thanks to R. King and P. Cramp for their general support, and contribution and maintenance of the aquarium facilities at the Australian Antarctic Division. We also thank an anonymous reviewer for constructive comments. This work was supported by the Tasmanian Graduate Research Scholarship and the Australian government’s Cooperative Research Centres Programme through the Antarctic Climate and Ecosystems Cooperative Research Centre (ACE CRC).

NOTES