Eating disorders, body image, and dichotomous thinking among Japanese and Russian college women ()

1. INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders are prevalent in industrialized and Western cultures. However, it is also known that ethnic and cultural differences are found in eating disturbances. For example, a previous meta-analytic study showed that white women living in Western countries experience greater levels of eating disturbances and body dissatisfaction than non-white women [1]. According to another recent meta-analysis [2], non-Western participants scored higher than Western participants on an Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) [3], both in normal and eating disordered samples. Although many previous studies focused on mean-level differences, it is also meaningful to illuminate differences in psychological processes between ethnic and cultural groups.

Individuals with eating disorders often have rigid cognitive styles [4]. Some types of cognitive styles act as triggers for bulimic behaviors [5]. The linkage between cognitive styles and eating disorders is not only observed in Western cultures, but also in Asia. For example, Ono and Shimada [6] reported that distorted thinking styles, such as irrational beliefs and a transfer-responsibility coping strategy, exacerbate the tendency toward binge eating and eating disorders among female high school students in Japan.

In particular, some studies have shown that an inflexible and dichotomous thinking style is related to eating problems. Such a thinking style leads to the classification of eating behaviors or food into strict categories of good versus bad [4]. Byrne, Allen, Dove, Watt, and Nathan [7] summarized that the cognitive style of dichotomous thinking may contribute to the maintenance of eating disorders in two ways. That thinking style contributes to the development of rigid dietary rules and increases the tendency toward binge eating following any transgression from these dietary rules. Byrne, Cooper, and Fairburn [8] developed the Dichotomous Thinking in Eating Disorders Scale (DTEDS) by using elements from other perfectionism and tolerance-of-ambiguity scales. Furthermore, they showed that dichotomous thinking is one of the psychological predictors of weight regain in obesity. In particular, their results suggested that a generally dichotomous thinking style was a key predictor of weight regain in obese people rather than dichotomous cognition relating specifically to food, weight, and eating. It was suggested that individuals with dichotomous thinking styles might interpret falling short of their weight loss goals as evidence of failure, which in turn may lead to the abandonment of all efforts toward weight maintenance or further weight loss [7]. Additionally, Lethbridge, Watson, Egan, Street, and Nathan [9] found that dichotomous thinking predicts eating disorder psychopathology in both women with eating disorders and normal women. Recently, a Dichotomous Thinking Inventory (DTI) was developed for general use in psychological studies rather than specifically for eating problems [10]. The DTI has good internal consistency and test retest reliability, and it has good validity from the perspective of correlations with other self-measures and characteristics reported by participants’ friends. This study uses the DTI because we focus on the effects of general dichotomous thinking on body image and eating disorders.

Another risk factor that maintains eating disorders is distorted body image. Body image disturbances have been hypothesized to play a central role in eating disorders [11]. Body image dissatisfaction, such as perception of a difference between real and ideal body images, correlates with symptoms of eating disorders [5,12]. Nakai, Imai, Kashitani, and Yoshimura [13] reported that patients with bulimia nervosa had smaller ideal values of waist and hip girth due to their body dissatisfaction, whereas patients with anorexia nervosa had smaller ideal values of waist and hip girth due to fear of maturity and interoceptive awareness. These results suggest that compared to normal people, patients with eating disorders have different criteria for the evaluation of ideal body image.

Thinness has been reinforced as an ideal body image for women by media and advertisements in Western cultures [14,15]. However, the same tendency is also observed in other cultures. For example, although there was no difference between actual and ideal body weight, desired body weights among Japanese female juniorhigh-school students were lower than their actual body weights, and their desired body weights were similar to those of Japanese celebrities [16]. Additionally, thinking style and cognitive distortions also have an influence on perception of body image [17]. Williamson et al. [4] claimed that dichotomous thinking is a factor that contributes to the classification of bodies as either “thin” or “fat” with no middle ground.

The aim of the current study is to explore the ef-fects of dichotomous thinking on eating disorders and to explore cross-cultural differences in this effect model between Japanese and Russian women. This study also focuses on the mediating effects of real and ideal body image on dichotomous thinking and eating disorders.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

A total of 606 female college students participated in the study, including 419 Japanese and 187 Russian women. The Japanese participants were students at four colleges located in suburban areas of Aichi, Gifu, Hokkaido, and Tokyo. The Russian participants were students at universities in Moscow. There was no significant age difference: mean ages were 19.8 years in Japan and 19.7 years in Russia.

2.2. Materials

Dichotomous Thinking. The Dichotomous Thinking Inventory (DTI) consists of three subscales [10]. A high score on the “Preference for Dichotomy” subscale implies a thinking style that is drawn toward distinctness and clarity rather than ambiguity and obscurity. A high score on the “Dichotomous Belief” subscale implies a manner of thinking that considers all things in the world as being divisible into two types, such as black and white, rather than treating things as inseparable and in-divisible. A high score on the “Profit-and-loss Thinking” subscale implies that one is motivated by an urge to gain access to actual benefits and avoid disadvantages. Answers on the DTI were given on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree); a Russian version of the DTI was also developed for this study. Cronbach’s alpha values for the DTI were as follows: α = 0.84 (Japan) and 0.80 (Russia) for the full scale; α = 0.72 (Japan) and 0.51 (Russia) for the Preference for Dichotomy sub-scale; α = 0.76 (Japan) and 0.79 (Russia) for the Dichotomous Belief subscale; and α = 0.72 (Japan) and 0.54 (Russia) for the Profit-and-loss Thinking subscale.

Stunkard Body Figure Scale (BFS). In order to assess real and ideal body images, nine figures of female body shapes that range from extremely thin to extremely obese were used. These figures were developed by Stunkard, Sorensen, and Schulsinger [18]. This figure scale has been widely used to assess perceived body images among many populations, such as people of various ages [19,20], people with type 2 diabetes mellitus [21], different ethnic groups [22,23], and people from different countries [24]. In this study, participants were asked to select their perceived and ideal body shapes.

Eating Disorder. In order to assess the participants’ tendencies toward eating disorders, the 26-item version of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) [25] was used. In order to assess whether participants have eating disorders, responses on the EAT-26 are generally coded as follows: Always, Usually, and Often are assigned values of 3, 2, and 1, respectively, whereas Sometimes, Rarely, and Never are assigned values of 0. Under this system, total summed scores above 20 are generally considered characteristic of subclinical eating disorder pathology. However, in this study, we score items continuously on a 6-point response scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 5 for each item; this maintains sensitivity to variation in a situation where many of the participants thought that they did not have eating disorders. Item 26 was reversescored using the same values. Possible scores on the EAT ranged from 0 to 130. The Japanese version of the EAT- 26 was developed by Mukai, Crago, and Shisslak [26], and the Russian version was developed by Meshkova [27]. We observed the following values of Cronbach’s alpha: α = 0.86 (Japan) and 0.91 (Russia) for the entire EAT-26; α = 0.86 (Japan) and 0.92 (Russia) for the Dieting subscale; α = 0.67 (Japan) and 0.74 (Russia) for the Bulimia and Food Preoccupation subscale; and α = 0.58 (Japan) and 0.68 (Russia) for the Oral Control subscale.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Eating Disorder

When scores regarding eating disorders scores were calculated using the 4-point system, the number of Japanese and Russian women who scored above 20 on the EAT-26 were 33 (7.9%) and 16 (8.6%), respectively. The cross-cultural difference between the ratios of women with subclinical eating disorders was not significant (χ2 = 0.08, df = 1, n.s.).

3.2. Cross-Cultural Differences in Body Image

Table 1 shows participants’ choices of real and ideal body shapes. No significant differences were found among the real body images of Japanese and Russian women. The mean real body image scores were as follows: M = 4.01 (SD = 0.94) for Japanese and M = 3.92 (SD = 1.10) for Russian women. A t-test showed no significant differences between the real body images, t = 1.08, df = 604, n.s. A significant difference was found between ideal body images among Japanese and Russian women: t = 11.65, df = 604, p < 0.001. Although Japanese women generally prefer figure sizes 2 and 3, Russian women generally prefer figure size 4.

3.3. Mean Differences on Scales between Countries

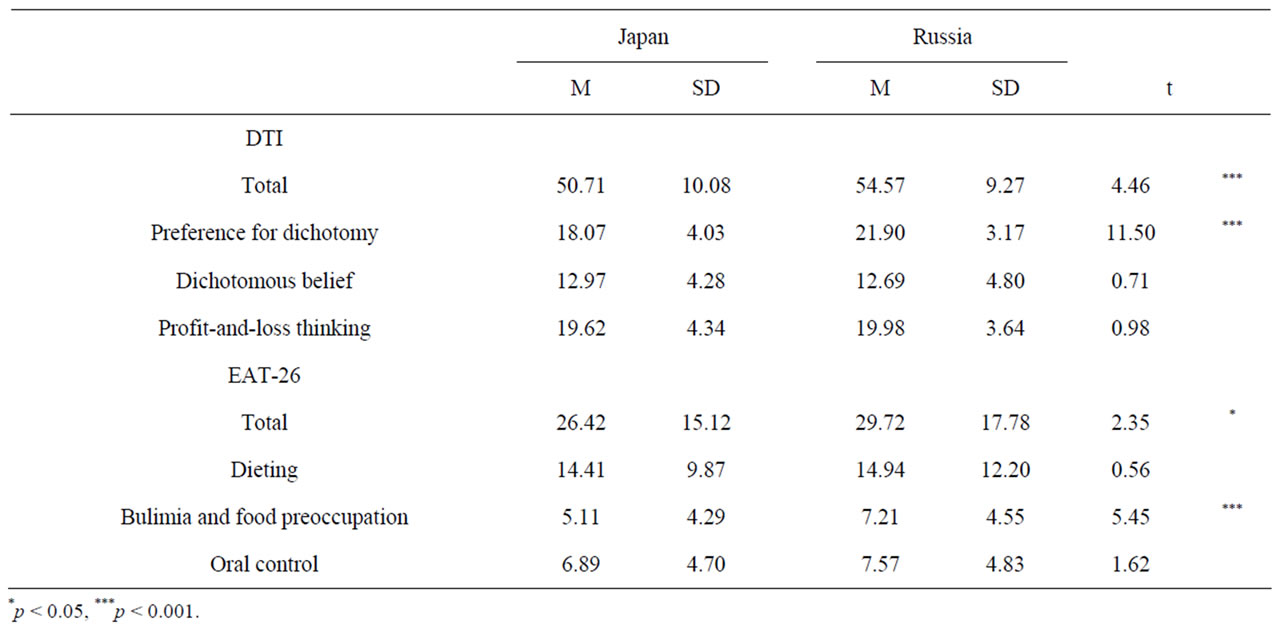

Table 2 shows the differences in each measured score between Japanese and Russian women. Total DTI and Preference for Dichotomy scores of Russian women were significantly higher than those of Japanese women, t = 4.46 and t = 11.50, respectively, df = 604, p < 0.001. Russian women also showed higher EAT-26 total scores and Bulimia and food preoccupation scores than Japanese women, t = 2.35, df = 604, p < 0.05, and t = 5.45, df = 604, p < 0.001, respectively.

3.4. Relationships among Variables

Table 3 shows correlation coefficients among the variables in each country. There were more significant negative correlations between dichotomous thinking scores and ideal body image in Russia than in Japan. The dichotomous belief subscale was positively related to EAT-26 scores only in Japan. Significant positive correlations were found between real and ideal body images in both countries. Real body image was negatively related with oral control, and it was positively related with dieting in both countries. The thinness of the ideal body image was

Table 1. Item choices for real and ideal body images in Japan and Russia.

Table 2. Differences in DTI and EAT-26 scores between Japanese and Russian women.

Table 3. Correlations among variables in each country.

positively related with all subscores of the EAT-26 in both countries.

3.5. Curvilinear Relationships between Dichotomous Thinking and Body Image

In order to test the nonlinearity of the relationships between dichotomous thinking and body image in each country, curvilinear regression analyses were conducted. Significant second-order polynomial regressions were found among ideal body image, DTI total score (R2 = 0.07, p < 0.01), and profit-and-loss thinking (R2 = 0.06, p < 0.01) in Russian women. These results indicated that people who have high DTI scores (especially those who have high profit-and-loss thinking subscores) tend to recognize that their ideal body images are either too large or too thin.

3.6. Cross-Cultural Differences in the Effects of Dichotomous Thinking on Eating Disorders

The measurement models of dichotomous thinking and eating disorders were validated in both Japan and Russia. In order to test for metric equivalence of the measurement models, all factor loadings of the DTI and the EAT-26 were constrained to be equal across the two countries. The result showed that the model is a good fit for the data; χ2 = 121.21, df = 36, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.063, and AIC = 193.21. Thus, we can test the structural models.

The model describing the effect of dichotomous thinking on eating disorders with the mediation by the body image was tested. When the weights of the direct paths from the dichotomous thinking to the eating disorders were constrained to be zero in both countries, the model’s indices of fit were improved; χ2 = 121.80, df = 38, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.060, and AIC = 189.80.

When all paths were constrained to be equal across the two countries, the indices of fit were as follows: χ2 = 129.43, df = 43, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.058, and AIC = 187.43. The best indices of fit were obtained when the weight of the path from dichotomous thinking to real body image was zero only in Japan, and the path from ideal body image to eating disorders was not constrained; χ2 = 124.71, df = 42, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.057, and AIC = 184.71. The result is shown in Figure 1. These results show that the effect of dichotomous thinking on real body image was significantly negative only in Russia and that ideal body image had a greater effect on eating disorders in Russia than in Japan.

4. DISCUSSION

The mean weight of Asians is typically smaller than that of Europeans [28]. However, there was no significant difference in real body image between Japanese and Russian women in this study. This result suggested that Japanese women overestimate their own body sizes, and/or Russian women underestimate their real physical sizes. The negative effect of dichotomous thinking on real body image among Russians suggests that Russian women with such thinking styles underestimate their own body sizes.

Figure 1. Model of dichotomous thinking, body image, and eating disorders.

Altabe [22] explored ethnic differences among American college students, finding that Caucasians showed more real-ideal body image discrepancy than did Asians. At the same time, the results of the present study indicated that female Japanese college students exhibited more real-ideal body image discrepancy than did female Russian college students; this effect was driven by the fact that Japanese women had thinner ideal body images than did Russian women, whereas no significant differences were found in real body images. The differences between our results and those of previous studies are believed to arise from environmental factors. Because all of the participants in Altabe’s study [22] attended the same college in the United States, they had many opportunities to compare their physical sizes with others. Asians were more satisfied with their own body sizes than were Caucasians in such cases. On the other hand, the Japanese women who participated in this study may compare their bodies with those of idealized Japanese women, for example, TV stars whose body sizes are typically thinner than normal.

Russian women showed higher DTI scores than Japanese women. Previous studies using the DTI scale [10, 29,30] have not explored differences between countries; therefore, the results of this study are the first cross-cultural findings using the DTI. According to a cross-cultural study [31], Japanese people show less avoidance of uncertainty than European people. These previous results suggest that lower dichotomous thinking tendency exists among Japanese people than among Russians. The results of this study are appropriate to that anticipated cross-cultural difference. In particular, it appears that Russian women tend to make more accurate judgments than do Japanese women, because the difference in the preference for dichotomy subscale between Japanese and Russian women was large (Cohen’s d = 1.01).

Dichotomous thinking seems to play a different role in determining body image and tendency toward eating disorders between Japan and Russia. As shown by the results of correlation analysis, Russian women with high scores on the DTI have leaner ideal body images than other Russian women. Additionally, there is a curvilinear relationship between dichotomous thinking and ideal body image among Russian women. Such clear effects of dichotomous thinking on ideal body image were not found among the Japanese participants. Japanese women who have high dichotomous-belief scores tend to show higher levels of eating disturbances than others. However, as shown by the results of structural equation modeling, the effects of dichotomous thinking on ideal body image among Russian women and on eating disorders among Japanese women were not necessarily direct.

The results of structural equation modeling suggest that dichotomous thinking has an indirect effect on eating disorders through the mediation of real and ideal body images in both countries. However, there were also some cross-cultural differences. In Russia, women who think dichotomously imagine their real and ideal body images to be thinner than those of others, and both real and ideal body images have effects on eating disorders. On the other hand, among Japanese women, dichotomous thinking has a negative effect only on ideal body image; their negative effect of ideal body image on eating disorders is smaller than that among Russian women.

From the point of view of individualism vs. collectivism, Japan and Russia seem to have similar cultures. For example, one study has claimed that both Japanese and Russian people are more collectivistic than Americans [32], and another study has suggested that Russian people are more collectivistic than are Japanese people [33]. However, the results of this study showed that Russian women tend to think more dichotomously than do Japanese women. Dichotomous thinking is related to individualism [34]; therefore, the results suggest that Russian women are more individualistic than Japanese women. In Russia, since the perestroika era of the mid- 1980s, there has been a revival of public and scholarly interest in developments taking place within the institution of the family [35]. Many Russian citizens believe that the main problem faced by their families is low income [36]. Such lack of economic stability and low family incomes may make young Russian people seek unambiguity, clear-cut answers, and dichotomous views. This matter is only the subject of mere speculation in this study; further investigation will be needed in order to clarify the relevant characteristics of recent thinking styles among Russian people.

It is still unclear whether the reasons for the differences found in this study actually stem from cultural differences between Japan and Russia. In this study, the path coefficients from dichotomous thinking to body image were very low. Further studies are required in order to explore whether the relationships among dichotomous thinking, body image, and eating attitudes are present in both countries and to explore these relationships in other countries that have individualist cultures.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (22730522) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

NOTES