ePROMs in the End of Life and in Making Ethical Decisions. An Integrative Review with Narrative ()

1. INTRODUCTION

In patient-centered care, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are the gold standard for efficiently assessing patients’ feelings, thoughts and complaints about a clinical intervention or disease [1].

Manuscript is here to view linked references. In this review, the tool we will be dealing with is electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs). They are defined by consensus as assessing the quality and effectiveness of healthcare measured and reported directly by the patient. The actual definition was introduced in 2017 by Medical Subjects Headings updated (MeSH) by the US National Library of Medicine. Traditionally, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), such as health-related quality of life, have been used at the aggregate level. However, these data are being used as a measurement tool in clinical trials, observational studies, and other studies as a primary way to record patient feedback [2].

As some studies show [3 - 5], a closer relationship between technology and healthcare has begun to develop, as seen in electronic health records (EHRs). Its origin dates back to the 1970s in the USA, but it was limited to academic purposes, and forms were still handwritten and stored on paper. In the 1990s, consumer electronics emerged, and the first Windows-based medical records were launched. In the 2000s, the information included in these records expanded.

Patient-reported outcome measurement, electronic health records and comparative effectiveness research have converged into a more patient-centered, technology-driven space.

Seeing these technological advances raises some questions: Are our palliative care physicians keeping up with this type of technology? Are they missing out on essential tools to address patient needs? The answer to this question may not be a mystery after all, according to one of the articles, “the use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is the gold standard for the assessment and treatment of physical and psychological symptoms, but many existing tools are not designed for use in a complex clinical setting.”

We use this statement to guide our study to find evidence that ePROMs are being used to their full extent in Palliative Care practice or end-of-life settings.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective was to establish and connect the three domains of this review, the first being their use at the end of life, the second the use of ePROMs and the third the ethical decisions involved in this type of patient.

Our Review Questions Were

Main:

1) How are ePROMs used in palliative care and in the care of life-threatening diseases?

Secondary questions:

1) Are ePROMs used to guide clinical decisions in end-of-life scenarios?

2) Do ePROMs have a positive impact on patients’ well-being?

3) Do ePROMs guide medical teams toward ethical decisions?

3. METHODS

An integrative review with narrative synthesis was performed. An integrative review is a specific review method that summarizes the empirical or theoretical literature to fully understand a particular health phenomenon or problem. The integrative review contributes to the presentation of diverse perspectives on a phenomenon of interest [6].

The advantage of this type of review is that many studies can be used to gather information related to the question at hand. Because of this perceived ease in collecting studies, the articles selected were of 10 different designs, including questionnaires in the clinical setting, Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT), Controlled Clinical Trial (CCT), secondary analysis, integrated knowledge translation approach, exploratory research, feasibility study, prospective randomized study, web based survey, observational study [7 , 8].

The research procedure consisted of three steps (Table 1).

The PICO model was used to define the criteria for assessing study eligibility.

![]()

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

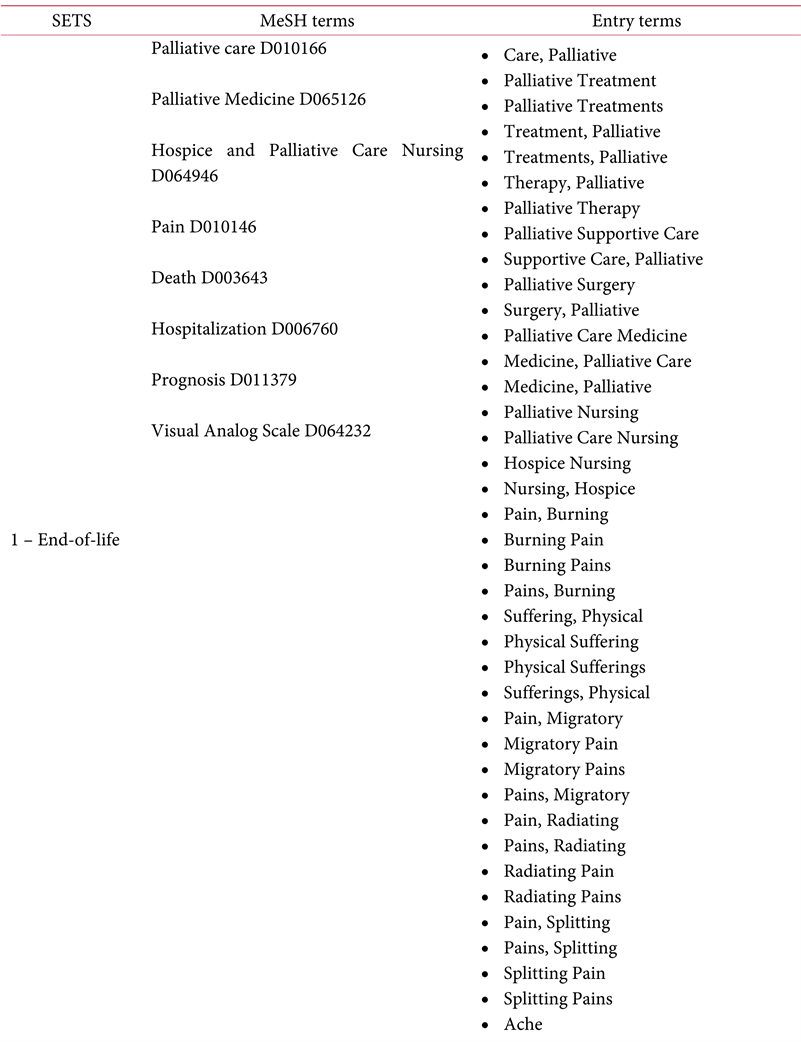

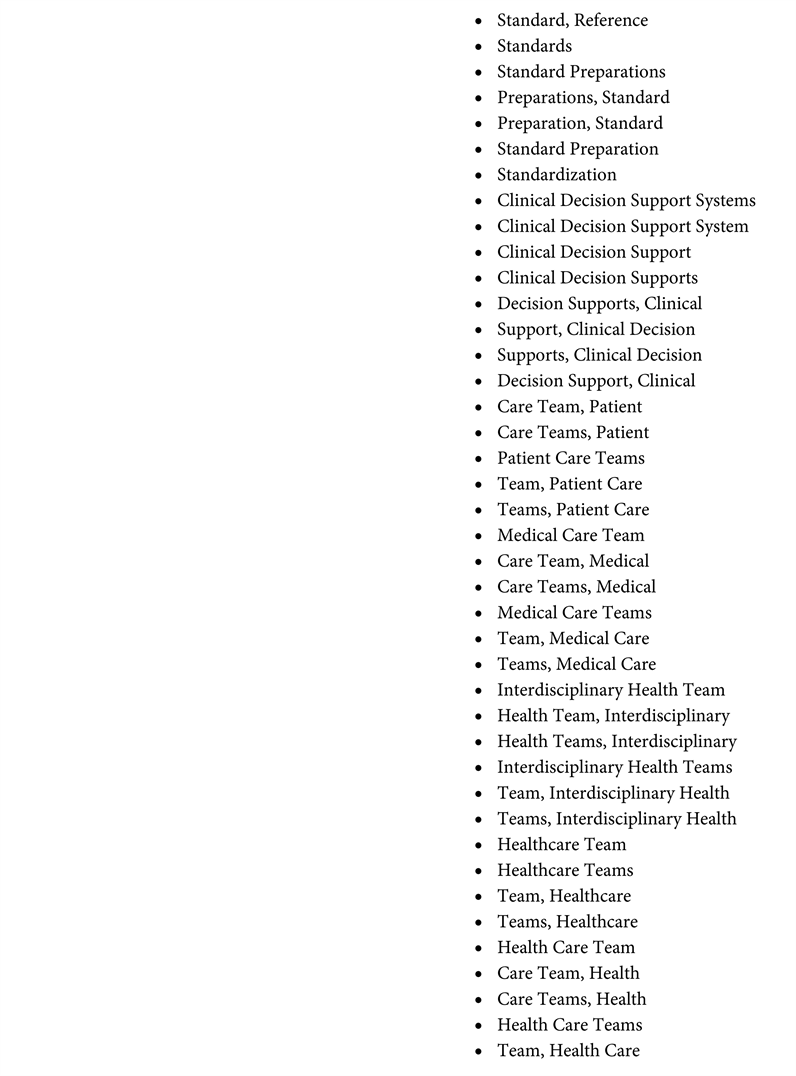

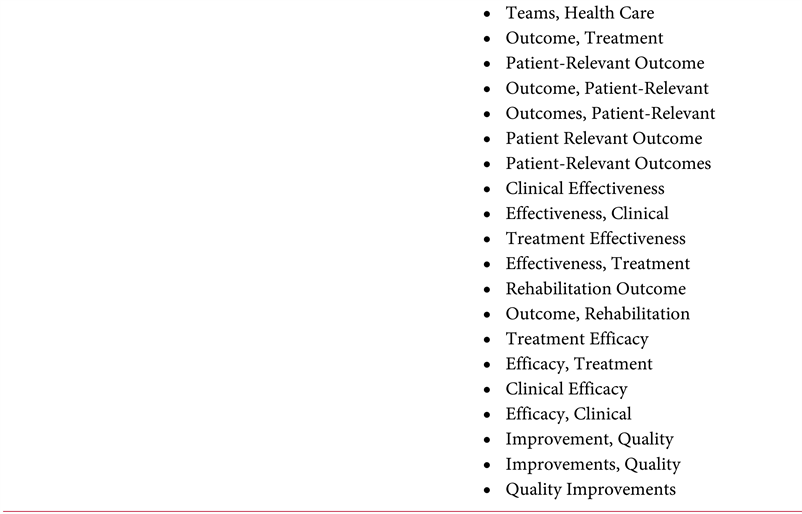

A computerized search strategy was performed with the PRESS (Peer Review Electronic Search Strategies) protocol to have a lower margin of error and increase the possibility that the records obtained were eligible for data extraction. We used this protocol to conform the search, using three keywords, MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and detailed entry terms. This initial search yielded 242 records (Appendix).

3.2. Characteristics of the Study

The results of this systematic review are based on 13 articles [9 - 21]. All data are compiled in Table, 3 divided into 8 categories: Authors; Journal; Year of publication; Participants involved.

Intervention studied; Context of use of ePROMs and study time; Results of the intervention and results needed for this specific review finally, the Design of the study.

3.3. Selection of Studies

Screening and selection were performed first on the title and abstract and secondly on the full text. Only full-text articles published in English and Portuguese were included. Additional information was collected on access to quality of life [22], randomized studies [23], and patient report articles in different specialties and mixed methods [23 - 26] (Table 2).

3.4. Data Collection

All data are compiled in Table 3 divided into 8 categories: Authors; Journal; Year of publication. Participants involved; Intervention studied; Context of use of ePROMs and years; Results of the intervention and results needed for this specific review and finally, the Design of the study.

4. RESULTS

The literature search and study selection results are shown in Figure 1. In summary, 235 records were identified after eliminating duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 104 eligible studies remained, and the full-text versions were reviewed. After reading the full text, 13 articles that met the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in this systematic review.

Full-text articles were retrieved through the first authors’ University accounts when a record was assessed as eligible.

From a total of 13 studies, data were extracted in several categories. The oldest article selected is from 2011, and the most recent report is from 2021, i.e., ten years. The mode is from 2018.

The most relevant articles were published during these years, which tells us that it is a relatively recent topic.

The ePROMs tend to have a role more akin to academic research tools; only recently has there actual use in clinical practice has been developed. However, much progress is being made, as evidenced by a

![]()

Table 2. PICOD method for data extraction.

study by Bausewein et al. “Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are used in clinical care (e.g., assessing the health status and needs of patients in a hospital at admission), audit (quality assurance of services) and research (e.g., studying the effectiveness of an intervention). The measurement of effects and outcomes on patients is also central to end-of-life (eol) care and the conduct of research in eol care”.

In terms of context, the most studied context is palliative care [8 , 10 , 11 , 15 , 16] with records involving its use in a PC setting (referring to the particular case of this review, since one of the research domains is end-of-life), followed by life-threatening conditions, with one record indicating that it was the main context of the study.

Regarding question number one of this review, the following frequency table illustrates the primary uses of ePROMs in clinical practice: As a response to the fourth question.

4.1. First Question

How are ePROMs used in palliative care and in the care of life-threatening diseases? (Table 4)

In this table, we report the number of items that refer to the specified items and which we consider the key ones. We have that the primary use of ePROMs, found in the 13 selected articles, is Quality of Life Assessment, followed by Symptom Burden and Simple Symptom Assessment. In third place, we see the decision to implement palliative care using ePROMs.

Finally, in a triple tie for fourth place, we found the Evolution of the disease and the use of prognosis, the Descriptive role (being that in the particular case of that study), was the description of the last six months of the patient’s life and was used for the Acquisition and provision of patient information to guide and train palliative care professionals.

4.2. Second Question

Are ePROMs used to guide clinical decisions in end-of-life scenarios? (Table 5)

![]()

Table 3. Extraction of data from the systematic review.

![]()

Table 4. Frequency analysis of ePROMs use in palliative care.

![]()

Table 5. Frequency analysis of ePROMs decision guidance.

These results in absolute values mean that in 61.5% of the included articles, the ePROMs added information and actively changed the course of thought of the professionals, practically modifying decision making. In 38.5% of the articles, ePROMs did not play an active role in decision making.

4.3. Third Question

Do ePROMs have a positive impact on patient’s well-being? The following frequency table illustrates the impact on the quality of life of patients who used ePROMs during their care (Table 6).

As can be seen, 61.5% of the selected articles had a positive impact on the patients’ quality of life. On the other hand, in 30.7% of the articles chosen, there was no impact on quality of life, and in 7.8%, there was a negative impact derived from the use of ePROMs tools.

4.4. Fourth Question

Do ePROMs guide medical teams toward ethical decisions?

![]()

Table 6. Frequency analysis of ePROMs impact on well-being.

![]()

Figure 1. The flowchart of the item selection process. This flowchart was based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

The table illustrates whether there was a direction that produced ethical decisions provided by ePROMs (Table 7).

We found an equal distribution between studies referring to an ethical direction provided by ePROMs and studies that demonstrated no order in terms of the ethical qualities of those decisions: only one showed that it negatively affected ethical decision making by leading clinicians down the wrong decision

![]()

Table 7. Frequency analysis of ePROMs in ethical decision management.

path. In relative terms, 46.15% of the articles referred to an ethical direction, 46.15% referred to no order, and 7.7% referred to an unethical approach.

5. DISCUSSION

From these results, we can draw some conclusions. For example, suppose we divide this discussion by review questions and apply a cut-off of at least 50% in the frequency analysis to consider an effect to be significant. In that case, we will be able to go deeper into the extracted results.

Considering the years of literature analysis, we can reiterate that these technologies are relatively new when applied to the PC setting. The ePROMs are a simple tool, a standardized questionnaire in digital format that does nothing more than be extraordinary in assessing patient metrics in a simplified and non-interpretative manner.

In the first review question, we concluded that ePROMs in the PC setting were most frequently used in quality of life and symptom assessments; this could be due to the nature of ePROMs to probe the patients to gain an in-depth understanding of their condition from their perspective.

No other tool collects as many raw data from patients as vital signs monitoring. Since vital signs monitoring is a non-holistic way of collecting QoL-related information, ePROMs pave the way as the best method to improve patient comfort in CP and end-of-life scenarios. Therefore, QoL and symptom assessment are of utmost importance in PC, as better QoL is synonymous with better quality of care. Therefore, these assessments are, and rightly so, the most described uses for ePROMs in palliative clinical practice.

In fact, new work is already appearing on the modification of PROMs for FACE-Q head and neck module scales [21].

We can look to the registries for approval of these claims, as one of the selected studies [13] indicated that formalized assessment of PROMs may increase clinicians’ attention to patient concerns that are often overlooked.

This means that these data, uninterpreted by clinicians, play a central role in determining patients’ most critical needs and help guide the course of treatment according to their needs and wishes.

Regarding the second question and considering the 50% threshold to be considered significant, we can deduce that ePROMs have a considerable impact on guiding clinical decisions, as 61.5% of the included reports described these tools as a driver of clinical findings in PC or end-of-life scenarios. This metric is paramount in deciding whether ePROMs are a valuable tool to consider in the future of palliative care. As the year’s pass and ePROMs become a more prevalent trend, we expect these results to increase as uninterpreted and unbiased information becomes a challenge and becomes a pressing need due to improvements in diagnostic capabilities and technologies that require the vision of skilled and trained professionals for interpretation. The fact that 61.5% of registries cite that ePROMs are guiding clinical decisions and that the selected studies are relatively new only reiterates the veracity of these claims.

The results of the third review question indicate that 61.5% of registries reported a positive impact on patients’ quality of life. The ePROMs improve quality of life, considering the 50% cutoff.

Our results are another argument favoring unbiased data being a good starting point for decision making.

As we have said before, improvements in QoL are synonymous with improvements in the quality of care in PC. The only study that was detrimental to QoL was when clinicians had a role in interpreting patients needed and inserted the data into the questionnaires, which completely defeats the purpose of ePROMs. This also means that there is a positive trend in which PA professionals are more committed to acquiring and applying specific ePROMs to address the views and needs of their patients. Although the results are positive, there is room for improvement as practitioners need to be more engaged to learn and correctly apply ePROMs to increase this outcome.

We measured the ethical direction of decisions when using ePROMs to question number four.

We did this by assessing in the core text of the selected studies whether they mentioned that decisions were made considering patients’ beliefs, concerns and general condition, the information provided directly by the ePROMs. Using the cut-off point of 50%, we deduce that EPROMs do not have a significant impact as far as ethical direction is concerned.

Ethical guidance was reported by 46.15% of the registries, just below the 50% cut-off. This means that although ePROMs technology is a valuable tool for clinicians and its practical use, it still has many hurdles to overcome to become an essential tool in ethical services. The exact number of records that reported no guidance.

6. CONCLUSION

This review concludes that it is necessary to remind professionals and patients that these tools exist and can be applied in many situations. If used correctly, they can provide a better quality of life and care for primary care patients and a better supply of information to professionals. In addition, healthcare administrators and managers are increasingly advocating the routine use of PROMs and PREMs because of their potential to improve person-centered care by ensuring that the perspectives and experiences of patients and informal caregivers are revealed and integrated into decision making and management.

7. LIMITATIONS

One of the main obstacles to this study is the low number of eligible reports used to conduct the systematic review. There are few registries, including ePROMs used practically and clinically in palliative and/or end-of-life care settings. In any case, more registries are needed to confirm and reiterate our results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the people who have contributed and provided information for the preparation of this article.

Abbreviations

ePROMs—Electronic Measures of Patient-Reported Outcomes

eol—End-of-Life

RCT—Randomized Clinical Trial

CCT—Controlled Clinical Trial

LC—Lung Cancer

GIC—Gastrointestinal Cancer

PC—Palliative Care

LFC—Life-Threatening Condition

QoL—Quality of Life

HFpEF—Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

PCOC SAS—Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration Symptom Assessment Scale

AppendiX