1. INTRODUCTION

Early intervention offers an excellent opportunity for successful treatment, and patients with schizophrenia could recover to a large extent. Good outcome is typically not sustained beyond two to three years as a significant number of patients develop treatment resistance [1-3]. One of the reasons for this resistance has implicated the presence of negative symptoms [4]. Negative symptoms are common and core features of schizophrenia which are responsible for much of the long-term disability and poor functional outcome [5,6]. These symptoms are seen in 35% to 90% of patients, and are generally resistant to treatment, with the exception of clozapine [7,4]. Second generation antipsychotics have claimed to have some success in treatment of negative symptoms though not without skepticism [8]. Recently, negative symptoms have been described in the early phase of the illness [9], first episode schizophrenia, drug naïve psychosis, and in ultra high risk (UHR) candidates [10]. Since negative symptoms are resistant to treatment, and lead to poor functional outcome it is likely that early identification in treatment of these symptoms may improve the outcome of schizophrenia [11].

This treatment resistance due to negative symptoms seen in first episode psychosis (FEP) or early psychosis may be attributed to neurobiological changes which precede the onset of symptoms in late adolescence and early adulthood [12]. This neurobiological basis has been demonstrated by changes in cognition and neuroimaging and offers a novel understanding of the illness [13]. Despite this understanding, few studies have been carried out to clarify the nature and prevalence of negative symptoms in first episode schizophrenia [14,15]. In general, negative symptoms correlate with severity of schizophrenia; therefore, some of the patients in the early phase of the illness are severe in their manifestation [16]. Further, it appears that treatment resistance sets in very early in the course of schizophrenia (reference). It has also been proposed that patients with negative symptoms are one of the endophenotypes of the illness [17], as such, it is important to identify, assess, and treat these symptoms at the earliest stage in order to increase clinical, as well as social outcome of schizophrenia.

Since not much effort has been done to understand prevalence and pathophysiology of negative symptoms in early psychosis, the questions regarding the presence of negative symptoms and its subtypes remain undetermined. The present study has been carried out to examine the presence of negative symptoms and its subtypes in patients in the early phase of schizophrenia at the time of their initial hospitalization. Our assumption is that significant number of patient’s exhibit negative symptoms at the time of entry into a treatment program, as such, they will also become hospitalized.

2. METHOD

Design: This is a prospective, cross-sectional cohort study of hospitalized first episode schizophrenia patients. The study was conducted in LT Municipal General (LTMG) hospital and Medical College which is a general teaching hospital in Mumbai, India. The Medical College Ethics Committee at LTMG approved the study and consenting patients were enrolled. We screened 100 hospitalized patients of which 72 patients were recruited. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 45 years, with a diagnosis of schizophrenia as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel-IV (DSM-IV), were receiving their first contact for treatment, and were currently hospitalized. Exclusion criteria consisted of the presence of an organic mental disorder, neurological illness, head trauma, pregnancy, epilepsy, mental retardation, and previous hospitalization.

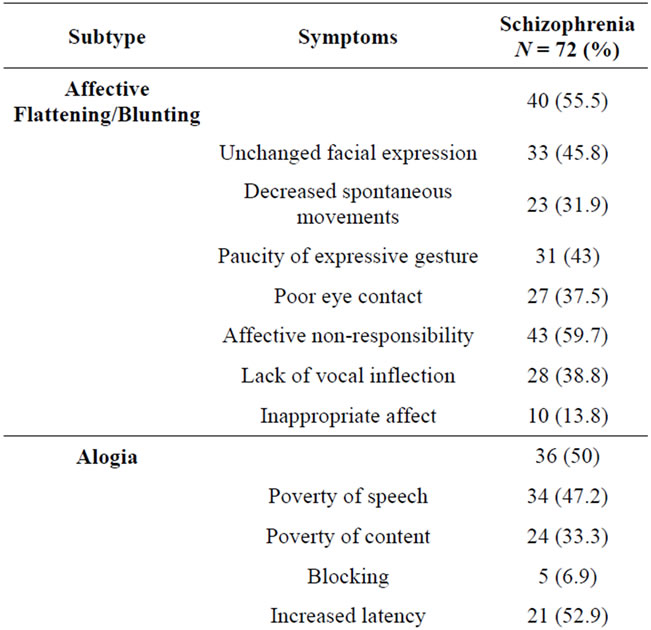

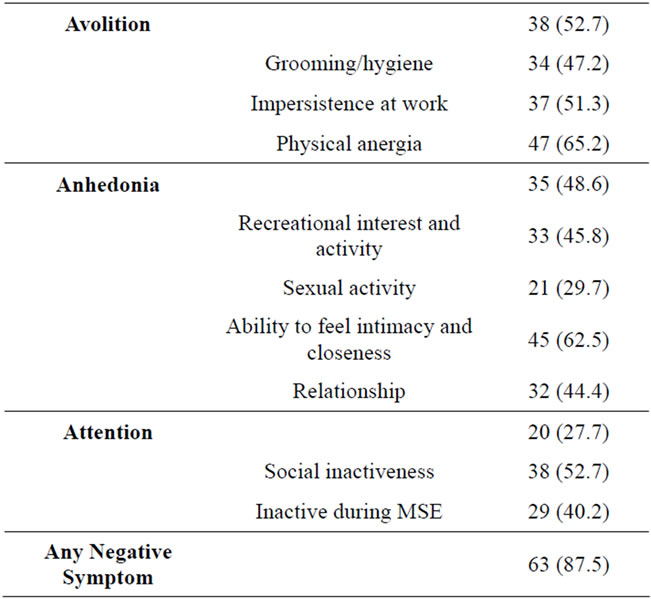

Assessments: Patients negative symptom severity was assessed using the SANS [18]. This 20 item scale is designed to assess the five subtypes of negative symptoms primarily occurring in schizophrenia, including affective flattening or blunting, alogia (slowed thought processes), avolition/apathy, anhedonia/asociality and difficulties with attention. Items are rated on a scale from 0 (none) to 5 (severe). A present (2 - 5) vs. absent (0 - 1) binomial variable was used in the analyses. Further, level of depression was assessed using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [19]; level of functioning was measured using the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF) [20], and severity of psychopathology was measured by the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGIS) [21]. Outcome criteria for presence of negative symptoms were determined by the number of patients having all five subtypes of negative symptoms present, namely: affective flattening, avoliton, anhedonia, asociality and inattention. We also assessed extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) clinically, i.e. the number of patients who were taking anticholinergic medications at the time of admission into the study.

Outcome Criteria: Typically negative symptoms are described in terms of primary and secondary symptoms; primary symptoms are those which have been known to be an integral part of symptomatology, while secondary symptoms are the signs which are clinically similar and mimic primary symptoms but are not the integral part of schizophrenia, rather they result from a number of other causes e.g. drug-induced akinesia, psychotic symptoms, social deprivation, and chronicity [22]. Differentiating primary from secondary negative symptoms in schizophrenia has become a focus of considerable attention within the past few years. Primary negative symptoms were operationally defined by the presence of all five subtypes of negative symptoms and was defined as a score of 2 to 5 on SANS for presence of negative symptoms on each 5 domain. Secondary negative symptoms were defined by the presence of at least one subtype.

3. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data was analyzed according to two main groups, and percentages were used as a means of comparison.

4. RESULTS

Sample characteristics are given in Table 1. Mean age for patients was 24.4 years, 53 patients were male, and 60 were married. Of the 72 patients with schizophrenia, 50 (69.4%) were diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, 9 (12.5%) were schizoaffective, 11 (15.28%) were residual, 2 (2.78%) were disorganized, and 1 (1.39%) was catatonic type. The mean duration of illness was 30.8 months and mean age of onset of illness was 20.7 years. Findings of psychopathology are given in Table 2. 66 (87.5%) subjects exhibited one negative symptom, while all five subtypes of negative symptoms were present in 34 (47%) patients. The most prevalent negative symptom in first-episode schizophrenia was found to be blunting (72%), to a lesser extent avolition (55.5%), anhedo-

nia (50%), attention and affective flattening (52.7%), and alogia(48.6%). The mean score for depression on HDRS was 23.1, and 46% of patients had significant level of depression (HDRS > 17). Overall psychopathology was severe, and 61 subjects scored more than 3 on CGIS. Level of functioning was significantly poor, measuring a

Table 2. Scale for assessment of negative symptoms (SANS) ratings.

score of 45.7 on GAF. We found that 45.8% patients were prescribed anticholinergic medications which indicated that at least 45% subjects had EPS requiring treatment.

5. DISCUSSION

Negative symptoms are a core characteristic feature of schizophrenia, and are recognized as one of the several domains of psychopathology. These symptoms are present not only in schizophrenia, but in a range of psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder [23]. The present study demonstrates 3 main findings: a significant number of patients had at least one subtype of negative symptoms (87.5%), and there was a significant number of patients (47%) who had all five subtypes of negative symptoms. This may be considered as primary negative symptoms due to operational criteria. Further and lastly, independently a particular type of negative symptoms was present amongst 48% to 76% of patients which was considered secondary negative symptoms. Negative symptoms are well known in first episode schizophrenia. Studies show that negative symptoms are present in a significant number of patients and its prevalence increases as treatment progresses resulting in long term, persisting symptoms even after remission [24]. Our findings highlight that a number of patients with secondary negative symptoms pose a therapeutic challenge for recognition and treatment of negative symptoms.

The prevalence of negative symptoms in FEP is high, 50% - 90%, and 20% - 40% of schizophrenia patients have persisting negative symptoms [25]. Severe negative symptoms during the early stage of treatment predicts poor prognosis. One study reported that these symptoms were present in 23% of subjects, which increased to 70% at the end of 3 years of treatment. The presence of these negative symptoms in early psychosis [24] is also associated with treatment resistance, indicating treatment resistance may potentially set in fairly early in the development of schizophrenia [26]. A study by Makinen (2010) [27], in a ten-year follow-up of FEP reported that 41% of the subjects had negative symptoms at the first episode, 39% in the follow-up phase, and 24% of subjects have persistent symptoms after 10 years. Another study reported the presence of persistent negative symptoms in about 27% of FEP patients with both affective and nonaffective psychosis [28]. Similarly, Bobes et al. (2010), reported that in a total of 1452 patients (60.6% male), one or more negative symptom was present in 57.6% of patients, with primary negative symptoms in 12.9% of subjects [29].

In addition, negative symptoms have also been found to be related to duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and level of functioning [30]. In a 5-year follow-up study by Bonostra et al. (year), shorter DUP was significantly associated with less severe negative symptoms at baseline, and also at short (1 - 2 years), and long term followup (5 - 8 years), and increased level of functioning in both UHR and early psychosis [31]. Recent work indicated that UHR cases who present with lower levels of negative symptoms and higher levels of social functioning are more likely to recover symptomatically, and no longer meet criteria for an at-risk mental state [32,33]. Due to consistent presence of negative symptoms in UHR candidates, measurement tools for psychopathology in at-risk individuals have included items about negative symptoms [34,35]. Our findings are consistent with what has been reported in the literature. Our study included patients who were admitted after duration of illness of 30 months, and illness onset at 20 years. They were hospitalized for the first time, and were not given adequate treatment prior to hospitalization.

In this study, a significant number (46%) of patients had a moderate level of depression on HDRS (14.3%) and 45% of patients were taking anticholinergic medications. A number of patients have EPS in first episode, these patients are more susceptible to EPS, all the patients were on second generation antipsychotics which also leads to EPS in significant number of patients, thus about 45% patients on anticholinergic is not surprising which might have mimicked the negative symptoms [36], and has certainly contributed to high incidence of secondary negative symptoms.

Negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia predict poor social outcome. The treatment options for negative symptoms are also extremely limited [37]. Various treatment strategies have been studied, in which several types of medications were added to antipsychotics in order to alleviate negative symptoms, for example adjunct antidepressants [38], lamotregene [39], mirtazapine [40] and other mood stabilizers [41]. Further identification and treatment of negative symptoms is important in order to improve outcome in first episode schizophrenia. This requires some thinking for identifying these symptoms and providing treatments which can specifically treat negative symptoms, for example, atypical antipsychotics, cognitive behavioral therapy and possibly the early introduction of clozapine [42,43]. This early introduction of clozapine has been proposed by the Texas Algorithm [44] and very few studies have shown positive response efficacy. Both pharmacological, as well as psychosocial interventions should be tried in the early phase of treatment [45]. A careful examination of patient’s cognitive and affective symptoms needs to be carried out in order to identify the presence of negative symptoms effectively [46].

6. LIMITATIONS

Important limitation of this study is absence of control group. Secondly, it is only cross-sectional, and change of the prevalence of negative symptoms within groups is not known. A longitudinal study is required to elucidate the presence of same features over certain period of time to study the changes in diagnosis. Thirdly, it has not been clearly brought out if these features are secondary, depressive symptoms, treatment effects, or secondary to psychosocial stress factors. Lastly, the nature of treatment resistance has not been tested. We feel that there is a merit in this pilot study in which a better design with adequate numbers is necessary.

7. CONCLUSION

This study shows that a significant percentage of patients with first episode schizophrenia, present with negative symptoms. About half of the patients who experienced a first time hospitalization in the first two and a half years of duration of illness have all five subtypes of negative symptoms which may indicate the presence of primary negative symptoms, and about 40% have secondary negative symptoms, and lastly 87% of patients presented with any one feature of negative symptoms. All five subtypes of negative symptoms are common, occurring in 48% - 70% of patients. Findings have implications for identification and early treatment for these symptoms in order to increase social and clinical outcome of schizophrenia. We conclude that negative symptoms are prevalent in about half of the patients with early phase of schizophrenia and early introduction of effective treatments can be of significance. Therefore, further research in this area is required.

8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Kristen J. Terpstra, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, McMaster University, 1280 Main St West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8.

NOTES

Funding: No funding was received for the preparation of this article.

#Corresponding author.