Lymphocytosis in Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Patients Infected by Helicobacter pylori ()

1. Introduction

The term idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) usually implies thrombocytopenia in which apparent exogenous etiologic factors are lacking, and in which diseases known to be associated with secondary thrombocytopenia have been excluded [1]. Adults ITP patients generally require several types of treatment strategies at the presentation because about a half of the patients presented with counts below 10,000 per cubic millimeter, resulting from accelerated clearance and destruction of antibody-coated platelets by tissue macrophages, predominantly in the spleen [2]. Antiplatelet antibodies also target antigens on megakaryocytes and proplatelets, variably suppressing platelet production [3]. The standard therapy includes oral gulcocorticoids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and splenectomy [4-6].

Since the first case report of Grimaz and colleages [7], several investigators have reported the association of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection with ITP [8-11]. They demonstrated a successful improvement of ITP after the eradication of H. pylori. In Several Japanese investigators reported successful platelet recovery in chronic ITP patients after the eradication of H. pylori [10-13]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between H. pylori and ITP. For one, antibodies against H. pylori, specifically against CagA protein have been shown to cross react with platelet antigens causing accelerated platelet clearance [14]. Other proposed mechanisms are modulation of host immunity following colonization by H. pylori to favor the emergence of auto reactive B cells and the enhancement of phagocytic capacity of monocytes together with low levels of the inhibitory Fcγ receptor IIB following H. pylori infection [15]. However, the restrict pathogenetic mechanisms of H. pylori-induced thrombocytopenia remain obscure. Therefore, we investigated the prevalence of H. pylori infection and performed a comparative analysis of a subset of H. pylori-infected patients with non-infected patients using the standard statistics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

From December 2001 to October 2002, we investigated the presence of gastric H. pylori infection in 30 adult ITP patients (two patients were with acute disease) consecutively admitted to National Center for Global Health and Medicine. ITP was diagnosed on the basis of the presence of isolated thrombocytopenia (platelets <100 × 109/L), marrow megakaryocytic hyperplasia and the absence of other known conditions causing thrombocytopenia. Informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Assessment of the Infection of Helicobacter pylori

We judged the patients as be infected with H. pylori using [13] C urea breath test (ABCR®; PDZ Europa limited, Cheshire, England), rapid urease test (Pyloritech®; Serim, Indiana, USA), and serum Ig-G antibody against H. pylori (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA).

2.3. Eradication and Assessment of Platelet Recovery

According to the recommendation of Japanese system of health insurance [16], patients with H. pylori infection were administrated standardized combination antibiotics therapy (amoxicillin 750 mg twice a day and clarithromycin 200 mg twice a day plus lansoprazole 30 mg twice a day for 7 days). H. pylori eradication was assessed by the [13], C urea breath test two months after the antibiotic therapy. The platelet count was monitored twice a month during the first year just after the start of combination antibiotics therapy. Response to treatment was defined as complete (CR) if the platelet count was above 150 × 109/L and partial (PR) if platelet count was between 50 and 150 × 109/L. All other patients were judged as non-responders (NR).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using StatView software (Version 5.0; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Clinical characteristics of the two groups of patients were compared using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The Student’s T test was used to analyze continuous variables. The paired T test was used to analyze the efficiency on platelet count and effect on lymphocyte counts after the eradication. The difference was judged as significant when P value shows less than 0.05.

3. Results

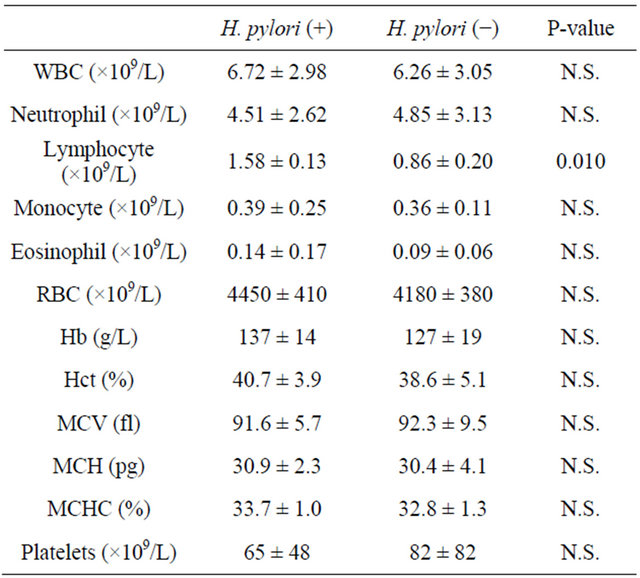

Table 1 shows the representative clinical features of patients at diagnosis, interval from diagnosis and therapeutic regimens. The study group consisted of 30 patients, including 12 men (40%), with a median age of 50 years (range, 20 - 83 years). The median interval between diagnosis and this study was 22 months (range, 1 - 60 months). We documented H. pylori infection by the urea breath test in 19/30 patients (63.3%). There was no significant difference between two groups in the distribution of therapeutic regimens performed. Table 2 shows the main hematological parameters at diagnosis. Lymphocyte counts of H. pylori infected cases were significant higher than those of non-infected cases (1.58 ± 0.13 × 109/L vs. 0.86 ± 0.20 × 109/L; mean ± standard deviation; p = 0.010). Other parameters showed no significance. H. pylori eradication was achieved in 17/19 (89.4%) H. pylori-infected patients. As far as platelet count was concerned, five of these patients achieved CR and nine patients reached PR. Five patients were non-responders. Overall, 14/19 H. pylori positive patients (73.6%) have achieved a significant response to antibiotic therapy. Among them, two patients with acute ITP achieved CR after successful eradication. The difference between the

Table 1. The representative clinical features of patients at diagnosis, interval from diagnosis and therapeutic regimens.

Y: yes; N: no; Combination:anabolic steroid + immunosuppressive agents + steroid; N.S.: not significant.

Table 2. The main hematological parameters at diagnosis.

Abbreviations: WBC: white blood cell; RBC: red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; N.S.: not significant.

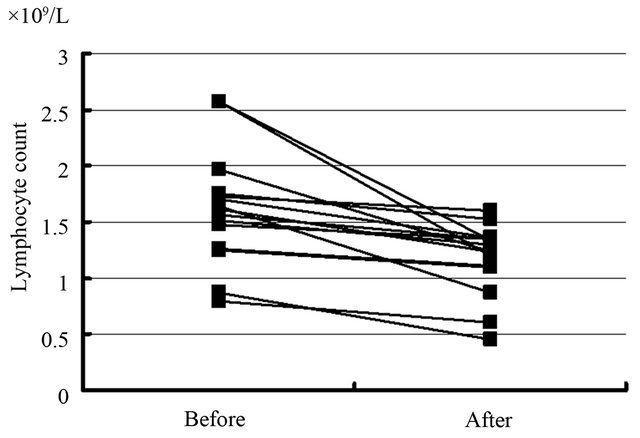

mean platelet count ± S.D. before and after H. pylori therapy is statistically significant (65 ± 48 × 109/L vs. 200 ± 140 × 109/L; p = 0.018) (Figure 1). In addition, the difference between the mean lymphocyte count ± S.D. before and after H. pylori eradication is statistically significant in responding patients (1.58 ± 0.13 × 109/L vs. 1.02 ± 0.43 × 109/L; p = 0.012)(Figure 2). There were no difference in the neutrophil counts and the eosinophil counts before and after the eradication.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in our series was 63.3% (19/30). This rate appeared almost equal to other previous reports. Our eradication rate was 89.4% (17/19), which is almost similar to other investigators [8-11]. The temporal profile of platelet counts of the 14 responding patients was similar to the literature (Data was not shown) [10]. Two patients with acute ITP were enrolled in this study. They achieved CR after the successful eradication. This fact suggests that acute ITP patients with H. pylori infection could achieve CR when the eradication therapy is successful.

We found that lymphocytosis was observed in H. pylori infected cases and lymphocyte counts were significantly decreased after the eradication in this study. Neurath et al. reported that mucosal immunity relied on the delicate balance between antigen responsiveness and immunological tolerance [17]. The polarization of T helper cells plays a key role in maintaining or disrupting this equilibrium. The signature cytokines of distinct Tcell subsets and the transcriptional regulation of T-cell differentiation appear to be of fundamental importance in mucosal immunity. In recent years, evidence has accu-

Figure 1. The platelet count increased significantly after the successful eradication of H. pylori. Each line indicates the eradication-effect against the platelet count of the H. pyloriinfected patient.

Figure 2. The difference between the lymphocyte count before and after H. pylori eradication was statistically significant in responding patients. Each line indicates the eradication-effect against the lymphocyte count of the H. pylori-infected patient.

mulated to suggest that in both human patients and animal models, host cellular immune response is an important determinant influencing the outcome of H. pylori infection. H. pylori-infected individuals express proinflammatory cytokines in their gastric mucosa (IFN-γ, IL-8), and the gastric mucosa is infiltrated with proinflammatory type 1 helper T cells (Th1)-biased lymphocytes as well as neutrophils and other inflammatory cell types [18].

In the literature, Semple and colleagues reported that the adults with immune thrombocytopenic purpura often had increased numbers of T cells, increased-numbers of soluble interleukin-2 receptors, and the cytokine profile suggesting the activation of precursor helper T and Th1 cells [19]. In these patients, T cells stimulate B lymphocyte to synthesize of antibody after the exposure to fragments of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa but do not after the exposure to whole molecule proteins [20]. The derivation of these cryptic epitopes in vivo and the reason for sustained T-cell activation has been still obscure.

In this study, we demonstrated that lymphocyte counts of H. pylori infected cases have been significantly higher than those of non-infected cases. There might be several mechanisms causing this lymphocytosis. Among them, two main pathways are considerable. The first possibility is that the numbers of Th1 cells increase in peripheral blood. The second possibility is that activated Th1 cells stimulate the proliferation of B cells which product the antibody against the fragments of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the relation between H. pylori infected ITP and the lymphocytosis. We suggest that the lymphocytes might play an important role in the mechanism of the case of ITP with H. pylori infection. Further studies must be undertaken to elucidate the mechanism of lymphocytosis using the analyses of lymphocyte subsets and cytokine networks.

[21] NOTES

[23] *Corresponding author.

[24]