Acceptance of American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy’s guidelines for endoscopy reports ()

1. INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy is a fundamental diagnostic and therapeutic tool for evaluation and treatment of GI disorders [1-5]. The endoscopy reports are the primary tool for documentation and communication of findings, diagnosis, treatment, and recommendations for subsequent care and also serve important administrative and legal purposes. Thus, high quality and completeness of endoscopy reports are essential [6,7]. However, several studies indicate that endoscopy reports are incomeplete and lack uniform content and terminology [8,9]. Incomplete and erroneous reports might have serious impact to the patients’ welfare and cause redundant examinations and reduced cost-benefit [10,11].

As a part of an initiative to improve endoscopy reports, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Standards of Practice Committee have prepared guidelines for the contents of endoscopy reports [12] (Table 1). The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality assurance Committee has generated recommendations for systematic image documentation [13] and the World Endoscopy Organization (WEO) has published a Minimum Standard Terminology (MST) [14-17]. These guidelines aim to make the reports more complete, standardized and objective. The applications of the guidelines in clinical practice may also permit continuous auditing and comparison of the activity in endoscopy units.

There is an increasing number of guidelines in all medical fields and there exist several barriers influencing physicians compliance to guidelines [18]. However, common acceptance of the guidelines is an important prerequisite for their application. Therefore we aimed to assess the acceptance of the ASGE guidelines for endoscopy reports in a cohort of Non-US endoscopists, and to assess which variables the cohort estimated necessary to record in the endoscopy reports. Furthermore, we wished to determine their acceptance of ESGE recommendations for image documentation. The acceptance to record some other widely-used quality indicators was also assessed. To our knowledge, the acceptance of guidelines for quality improvement in GI endoscopy have never been tested

Table 1. Items to be recorded according to ASGE guidelines for endoscopy reports [12].

before in a cohort of endoscopists.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

An e-mailing list including 137 experienced endoscopists, based upon two congress registries, the mailing list of the Norwegian part of Scandinavian Association of Digestive Endoscopy and personal mailing lists were used to invite endoscopists to participate in this survey. Nonresponders received three e-mail reminders before the study was closed.

A web-based survey tool developed at the University of Oslo was used to perform this study (https://wo.uio.no/as/WebObjects/nettskjema.woa). A total of 34 items were addressed, of which 25 concerned the ASGE guidelines, 1 concerned the ESGE guidelines for photo documentation, and 8 questions dealt with administrative, widely-used quality indicators and present and future documentation system issues. The assessed items were (items included in ASGE recommendations marked with#).

2.1. Medico-Legal Mandatory Items

Patient name#, date of birth#, date of procedure#, and name of endoscopist#.

2.2. Medical Record Data

Reason for the examination#, relevant medical history#, medical history specified into past and present, physical examination#, treatment recommendations# and follow up#.

2.3. Technical Items

Technical limitations# with the additional specifications “technical difficulties to perform the examination”, “time to reach the duodenum/cecum”, “time spent on the examination”, “quality of bowel preparation”, “use of fluoroscopy/SopeGuide™ (Olympus Corporate Tokyo, Japan) in colonoscopy”.

2.4. Recording of Staff Identity

Name of the assistants.

2.5. Documentation Systems

Present text and image documentation system, and the endoscopists’ consideration regarding future systems for text and image documentation.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean percentages with 95% confidence intervals constructed by using the Student procedure [19]. The analysis was performed with JMP statistical package from SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. RESULTS

80 (60%) of the 137 endoscopists responded. 90% (95% CI 81 - 96) of the responders considered the endoscopic appointment to be a complete or partial consultation at a GI specialist’s and not only a technical examination.

3.1. Medico-Legal Mandatory Items

All responders agreed the medico-legally mandatory items to be included in the medical record (patient name#, date of birth#, date of procedure#, and name of endoscopist#). However, (10%, 95% CI 5 - 19) did not agree that the personal national ID number usually used to identify Norwegian individuals should be included.

3.2. Medical History, Physical Examination and Recommendations

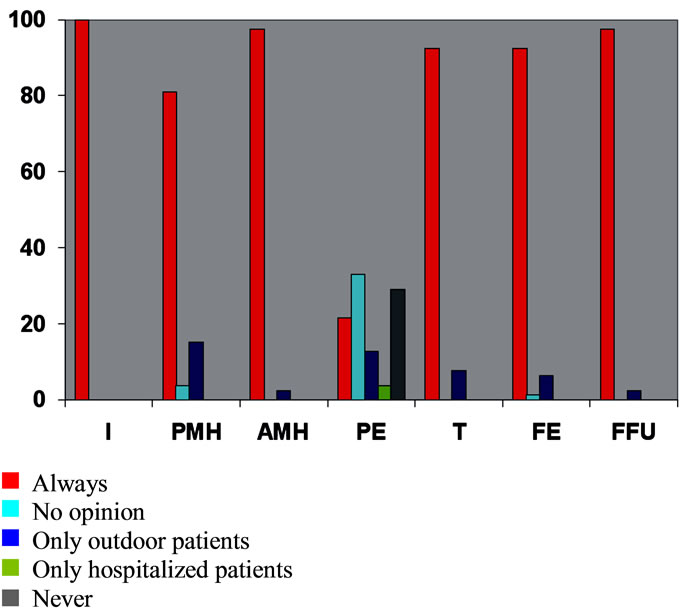

The vast majority 81% - 100% of endoscopists considered the reason for the examination#, previous medical history, actual medical history, and advice given on treatment and follow-up to be included in the endoscopy report (Figure 1). However, there were divergent opin-

Figure 1. Necessity of reporting items of medical history and dispositions, computed as percentages of endoscopists replying to the different answer categories (n = 80). I = indication, PME = previous medical history, AMH = actual medical history, PE = physical examination, T = medical treatment, FE = further examinations, FFU = further follow up.

ions on the need for documenting physical examination# with only 22% (95% CI, 14 - 32) saying that it should always be documented (Figure 2).

3.3. Medication

76% (95% CI 66 - 84) of the responders agreed that the use of pre-medication should always be recorded, whereas 24% (95% CI 16 - 35) considered that this should only be recorded if pre-medication has been administrated.

3.4. Technical Items

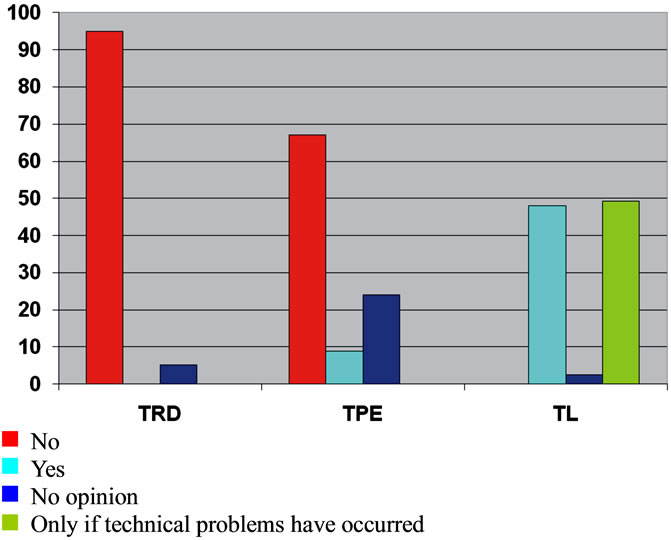

48% (95% CI 37 - 59) consider it necessary to always record technical limitations# to upper GI endoscopy (Figure 2). In contrast, 66% (95% CI 55 - 75) considered it necessary to record this variable for colonoscopy (Figure 3).

3.5. Text Documentation

At present, 63% (95% CI 52 - 73) of the endoscopists generate their endoscopy reports in a dictated free-text system, 35% (95% CI 26 - 46) in a semi-structured computer-based system and 1% (95% CI, 0 - 7) in a structured menu-driven system. However, 85% (95% CI, 75 - 91) consider that a menu-driven semi-structured system would be most appropriate in the future.

3.6. Image Documentation

The vast majority of endoscopists have some sort of im-

Figure 2. Percentages of endoscopists estimating the necessity of reporting technical items of the colonoscopy (n = 80). BC = bowel cleansing, TRC = time to reach cecum, TPE = total time to perform examination, TL = technical limitations, G = use of external guide (SopeGuide™ or fluoroscopy).

Figure 3. Percentages of endoscopists estimating the necessity of reporting technical items in upper GI endoscopy (n = 80). TRD = time to reach duodenum, TPE = total time to perform examination, TL = technical limitations.

age documentation modality; 82% (95% CI 72-89) photo printer, 36% (95% CI 27 - 47) VHS reorder. However, only 9% (95% CI 4 - 17) considered it necessary to perform image documentation routinely, 4% (95% CI, 1 - 11) did not have any opinion, and 87% (95% CI 78 - 93) considered it necessary only if pathologic findings were detected.

3.7. Staff Identification

All responders considered it necessary to record the name of the endoscopist# in the report. However, even if it is recommended to record the name of the assistant#, only 23% (95% CI, 15 - 33) of the endoscopists considered it necessary.

4. DISCUSSION

Mainly, this cohort of Non-US endoscopists agrees to current ASGE guidelines for endoscopy reports concerning medical information items, except for the need to record findings of the physical examination. However, technical items are considered less important, particularly in upper GI endoscopy. There was poor acceptance of the ESGE guidelines for systematic image documentation. This may be related to the endoscopists’ limited access to electronic systems for image documentation.

The study has some limitations; the response rate of 60%, on the lower limit of acceptable, may be due to limited in-hospital Internet access and to the limited possibility of only inviting physicians performing endoscopy on a regular basis.

However, we believe that the cohort is representative of Norwegian endoscopists, but we are not able to exclude bias in terms of non-representative proportions of surgeons/medical gastroenterologists, older/younger endoscopists, academic/non-academic endoscopists.

Variables like the time spent to reach the cecum and total examination time (and subsequently withdrawal time); cecum intubation rate and quality of bowel cleansing are widely-used quality indicators in colonoscopy [20-24]. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 2, many endoscopists in the present survey did not consider these variables to be important to be recorded. This may reflect an inadequate level of consciousness towards accepted quality indicators, or a conscious neglect if the endoscopists consider these indicators not to measure quality. Also, it has to be considered that exposure of suboptimal performance may be a personal threat to some. Obviously, education and debate regarding the establishment and implementation of quality indicators in colonoscopy is necessary in the future.

There is an increasing focus on the efficiency and quality of medical care. Medical records, including endoscopy reports play a fundamental role to reach this goal and perform high quality care [20,25]. Recent works of ASGE, ESGE and WEO to standardize the endoscopy reports are important initiatives to reach this goal. This standardization may also make international multicentre collaboration, comparison, audits and quality assurance easier [26-32]. These guidelines do, however, need continuous updating to include recently determined quality indicators, e.g. withdrawal time during colonoscopy, which has been shown to significantly affect the detection rate of colonic polyps [33-37].

It is estimated that related to endoscopic activity, 400 variable data fields are generated for every procedure [38]. However, it is a challenge only to record items required to secure high quality care and cost-effectiveness.

We estimated that the results of the survey would be influenced by how endoscopists consider the role of the endoscopic examination. However, one has also to keep in mind that the vast majority of endoscopic examinations in Norway are performed on an open access basis. Interestingly, the vast majority of participants consider the endoscopic examination as a specialist consultation requiring the same medical decision-making as any other specialist consultation. This may explain why the respondents in the present trial nearly fully agree to ASGE guidelines regarding the medical history of the patient. However, only 25% considered that it is required to document findings of an eventually physical examination.

In the present study, endoscopists considered medical information more important than administrative information. However, the importance of such information is probably increasing because it might be an important tool to organize the ward cost-effectively.

At present, a majority of endoscopists use transcription based free-text. Nevertheless, a vast majority consider that computerized systems will be the most appropriate tool in the future, indicating that physician skepticism towards these systems is limited. This fact is supported by studies showing that data entry in structured systems is fast, complete and well accepted [39-45].

A major advantage of structured CEMR is the automatic generation of databases. Thus, automatic coding for e.g. ICD and NCSP may also be implemented.

Norwegians endoscopists do not support the ESGE’s recommendations for systematic image documentation, even if it probably would render the reports more objec- - tive. Partially, this might be explained by cumbersome image documentation systems in most endoscopy units today. However, the compliance to these recommendations might improve by implementation of more userfriendly and efficient image documentation systems. The quality issue of photographic documentation has been an issue particularly in radiology for about ten years [46-48]. With competitive imaging methods like CT colonography coming up, this issue should no longer be neglected in gastrointestinal endoscopy.

5. CONCLUSION

The present survey has shown that this cohort of endoscopists is mainly in favor of more standardized and structured reporting systems.

ABBREVIATIONS

ASGE American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy CEMR Computerized Endoscopic Medical Record ESGE European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy GI Gastrointestinal ICD International Classification of Diseases MST Minimum Standard Terminology NCSP NOMESKOS’ Classification of Surgical Procedure WEO World Endoscopy Organization