Internal Migration and Women Empowerment: A Study on Female Garments Workers in Dhaka City of Bangladesh ()

1. Introduction

Women empowerment is still one of the burning issues and major concerns in today’s world, especially in developing countries. Women constitute one half of the world population, and empowering women is indispensable for economic, social and community development and global peace. Empowerment may be understood as the expression of freedom and ability to make a choice; women’s empowerment refers to the expansion of their ability to make strategic life choices in a context where they have been systematically denied access to resources to build such ability (Kabeer, 1999). It is a broad concept that encompasses many areas including economic, social and political empowerment. Accordingly, we can measure the empowerment of women through a number of indicators. In the past decade, Bangladesh has become a role model for the world in the area of women’s empowerment. Bangladesh has secured the 47th and 48th positions in the years of 2017 and 2018 among 144 and 149 countries respectively with regards to empowerment of women measured on multiple indicators (The Global Gender Gap Report, 2017, 2018).

The number of working women in the country has increased to 18.6 million in 2016-2017 from 16.2 million in 2010. Also, the number of female students’ enrollment in educational institutions has increased, and this is very important for the empowerment of women in Bangladesh context. Nowadays women are also working in various sectors. Their participation in formal and informal economic sectors has increased at a significant rate. All of these advancements and improved socioeconomic conditions lead to women’s empowered status. According to a recent ILO report, the total number of employed people in Bangladesh stood at 63.7 million of which 28.4% or 18.1 million were women (ILO, 2017). Back in 2010, the female labor force consisted of 1.72 crore women among which 13 lakhs were employed in the formal sector (Bangladesh Labor Force Survey, 2010). This shows a rapid rate of increase in women’s employment in the past few years. Interestingly, the size of the female labor force in the country has increased from the 2015-2016 to the 2016-2017 fiscal years at a significantly higher or faster rate compared to the increase of their male counterpart. In fact, the size of the female labor force has increased by 4.6% (BBS, 2017). The informal sector however, comprises the major share of female employment which is about 89% of the total (The Daily Star, 21 February, 2019).

On the other hand, women comprise slightly less than half of all international migrants (IOM, 2016). Migration refers to the movement of people from one place to another—either across an international border or within a state. There are two basic types of migration; one of them is internal migration while the other being external. Internal migration refers to the movement of people from one defined area to another within the national borders of a country. In 2017, the number of international migrants in the world has reached 258 million (UN DESA, 2017) whereas the number of total migrants was 59,037 in 2019. The total number of overseas employment of female workers was 11,603 in 2019 and the number increased to 809,298 from 1991 to 2019 (BMET). Migration can be both a cause and a consequence of female empowerment (Hugo, 2000). Pull and push factors lead women to migrate just as they do for men too. When women become educated and engaged in employment in various work sectors, then they eventually migrate from rural to urban areas for better opportunities and prospects for a better life.

Large scale migration for women is a relatively recent phenomenon in Bangladesh. Nowadays women are increasingly becoming a significant part of national and international movement and migration. Traditionally women’s engagement has been confined to the areas of household chores, reproduction and childcare, and to some extent, household or community management. But in recent times these trends have changed tremendously. Women are increasingly migrating on their own to avail enhanced economic opportunities. They often migrate for family purposes too. Currently women leave their previous homes for a wide range of reasons and in a wide variety of ways. Such Migration may bring many opportunities to change not only women’s standards of life but their identity as well. It can potentially result in transforming traditional norms as women gain better access to education and economic opportunities (Martin, 2004). In Bangladesh, internal migration is a regular occurrence where a large number of people migrate from the periphery to the larger metropolitan cities. Needless to say, a significant number of women make these internal migrants. As they migrate from the periphery to the center, some positive changes likely occur in their overall social status and quality of life. It was assumed that women’s empowerment would be related to such internal migration in a number of ways. Thus this study intended to explore the relationship between internal migration and women empowerment in the primate city of Bangladesh.

The main objective of the present study was to examine the state of women empowerment before and after migration from the rural area to the big city. The research question was: Does women’s migration within Bangladesh contribute to their empowerment? The researchers investigated and measured the status and conditions of the study sample along a number of indicators of women empowerment before and after their movement, relocation and settlement in the city. Additionally, the researchers explored the changing socioeconomic status of the respondents in order to understand their level and extent of empowerment. This paper presents the positive influence of internal migration as a demographic and socioeconomic process of empowerment of migrant women.

2. Review of Relevant Literature

A large number of studies have been conducted in Bangladesh as well as throughout the world relating women empowerment to migration. In order to identify research gap, relevant literatures have been consulted. Presser and Sen (2000) have considered women’s empowerment as a demographic process. They have provided critically important insights into the causes and consequences of population change, migration being one of those. Martin (2004) has addressed both the opportunities for empowerment of women and the challenges and vulnerabilities women face in the context of migration and movement nationally as well as internationally, and then highlighted the importance of possible policy recommendations to improve their situations. Ghosh (2009) stated that women are increasingly gaining significance as national and international migrants and that the complex relationship between migration and human development evidently operates in gender-differentiated ways. However, an explicit gender perspective is necessary to understand and address this because migration policy has typically been gender-blind. Gaye and Jha (2011) have highlighted some of the challenges to quantitatively measure the impact of migration on women empowerment. Exploring women’s international migration, Fleury (2016) has emphasized the positive relationship between migration and women empowerment, and highly recommended the protection of the human rights of migrant women. She also stressed that the government should ensure their access to services and resources. Oishi’s fieldwork (2005) with Filipino migrant women has shown that migration imparted positive effects on women with nearly 90% of the respondents reporting that they experienced positive changes, such as increased self-confidence and skill-set, even though the majority of them had been exploited and/or harassed at the same time.

It is observed from the review of the above mentioned literatures that sufficient numbers of studies have been conducted on migration and migrant women’s empowerment as well as on the different aspects and nature of such empowerment. The research has mainly focused on international migration and its effects on both the sending and receiving countries. There is a dearth of research that examined internal migration separately and the relationship between this type of migration and women empowerment exclusively. This study is one of the few ones that explore this specific nexus, particularly in the current Bangladesh context. Therefore, the present study sought to understand the interrelations between internal migration and women’s empowerment in a Bangladesh city by using a sample of female workers from the readymade garments sector in the country.

3. Significance of the Study

Women empowerment as a research topic and area has gained significant attention from scholars, academic and community researchers and activists around the globe. Despite constituting half of the Bangladesh population, a large number of women still face socio cultural, economic, gender and other barriers to equal participation in educational, employment, economic and civic engagement and many other spheres in life. Empowerment of this large group of women is thus a necessary and relevant issue, and research on this topic is still timely and important for providing evidence-based policy directions, especially in the current context of the rapid economic growth and development in the country. In the last decade, a large number of women from the rural and less urbanized communities or smaller cities have migrated to the capital city of Dhaka and become involved in paid work in many different sectors and industries. Though much research has been conducted to understand various aspects of migration in general, including women empowerment and its relationship with international migration worldwide, the interconnections and interactions between internal migration and women empowerment have been neglected in social sciences research. There have been huge numbers of research on the female garment workers in Bangladesh; but their socioeconomic status and level of empowerment have not been examined or understood in relation to their internal migration patterns. The current research, exploring migration within the country as the hidden or underlying influence and condition for women empowerment, will fill up this research gap. Findings from this study will potentially help the nation achieve the gender equality goal (Goal-5) for sustainable development. National and regional policymakers can adopt new policies to support women’s socioeconomic engagement through adequate service and resource provisions because their full participation in all spheres of life is essential not only for their empowerment but also for sustainable economic and social development of Bangladesh.

4. Theoretical Framework

Women’s empowerment has often been viewed through western feminist theoretical lenses or through economic development theories of the west. Such theories seem inappropriate to understand and explain the situations of all women in a country like Bangladesh. The present study aimed to understand and describe women empowerment on the basis of their economic activities and in the context of their economic empowerment which is compatible with the Women in Development or WID approach to improving women’s status. WID theories mainly focus on women’s productive role and engagement in income generation process, but often ignore the reproductive aspects and gender relations (Mosse, 1993). This approach emphasizes women’s social status, and aims at making women visible in the development process (Erwer, 2000). The theoretical framework includes several concepts and methods: equity, antipoverty and efficiency approaches to involve women in developmental activities and policies. The equity approach has also been called integrationist approach as it prioritizes productive roles, employment and economic independence as crucial factors for women’s empowerment and wants to shift the focus on their reproductive roles. The anti-poverty approach, the second most important WID agenda, emphasizes on reducing income inequality between men and women rather than reducing inequality in general (Mosse, 1993). Poverty reduction is the main goal of this approach and it primarily focuses unfulfilling basic needs, women’s responsibility for the family’s wellbeing and their role in the fight against poverty (Erwér, 2000). The efficiency approach is the third one under WID that became popular during the 1980s. The approach wants to see women as active participants in the development process. It may happen in different ways such as, through small investments, micro-credits and such other initiatives. The aim of the last or latest WID approach is to increase women’s productivity based on the assumption that efficient development requires women’s full engagement in productive roles. Similarly the present study has highlighted the influence of migration on women’s ability to be productive and to engage in income earning activities leading to their empowered status. The researchers assumed the liberating and empowering effects of migration on women’s economic and development activities, and thus this research has been guided by the WID framework to understanding women empowerment.

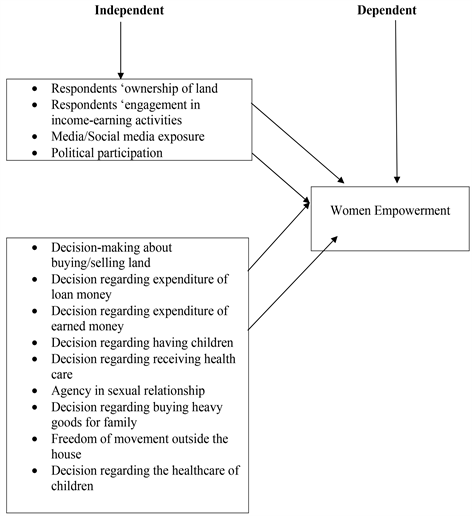

5. Conceptual Framework

6. Research Methodology

This study is descriptive and exploratory in nature. But both qualitative and quantitative methods have been employed to execute the research properly through the use of social survey as well as the case study approach. A small number of case studies were completed with select respondents from the sample to gain more details and deeper insights of the women’s situations. A questionnaire, checklist, camera, mobile phone, tape recorder were used as the tools for collecting primary data. Besides, survey interviews, in-depth interviews, empirical observations were additional techniques of collecting primary and supplementary data. A structured questionnaire was prepared to interview selected respondents. According to the need of the present study, both primary and secondary sources have been used to collect data. Secondary data has been collected from the organizations, publications such as books, journals, internet, newspapers, reports, and other studies on the topic.

This study has been carried out with the female garments worker in a factory based in Dhaka city, the capital of Bangladesh. There were 6300 women working in the garments factory. A total of 136 women were selected in the sample. These women had migrated from the periphery to the primate city within the last 10 years before they started working in garments factory. The sample size was determined by the sample calculator of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) which is 10% of the total population (Confidence Level = 95%, Population Size = 6300, Proportion = 0.1, Confidence Interval = 0.05, Confidence Interval: Upper = 0.15000 and Lower = 0.05000, Standard Error = 0.02551, Relative Standard Error (RSE) = 25.51, Sample Size = 136). An individual has been considered as a unit of analysis in the present research. To process, categorize and analyze the primary data a number of statistical methods such as classification, tabulation, frequency distribution, and the percentage have been employed with the aid of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.

7. Result

7.1. Socio-Economic and Demographic Condition of the Respondents

Social and demographic contexts are important to understand human behavior, their attitudes, emotional, mental and empowerment states and many other aspects of life. Socioeconomic, environmental, cultural and other issues and facts of human life are not always discrete and rather interconnected to each other. As Ritzer (2008) notes, facts of human life are influenced by each other. Women’s migration experience and their empowerment state similarly may not be separate facts; these are possibly connected to each other and also many other social aspects of their lives. In order to understand the socioeconomic status of the respondents, the following data have been collected and summarized below:

7.2. Internal Migration and Women Empowerment

The present study has explored the influence of internal migration on women empowerment. In doing so, the researchers measured and determined the association of internal migration on several indicators of women empowerment: respondents’ ownership of land, engagement in income-earning activities, decision-making about buying/selling of land, involvement in decisions regarding expenditure of loan money, expenditure of earned money, receiving health care for themselves and their children, decisions regarding sex and having children, media exposure, social media exposure, decisions regarding political participation, movement outside the house and buying very important goods for family. In other words, the respondent’s empowerment status was detected and interpreted by their responses about the different positions along the different indicators of empowerment before and after migration to the national capital city. The influence of internal migration on these women’s empowerment level as represented by their response to the different indications is described below:

7.2.1. Ownership of Land before and after Migration

Ownership of land is a crucial indicator of women empowerment. Table 1 shows a positive change in land ownership after migration. Before migration, only 13.2% of the respondents had ownership of land. On the other hand, an increased number of women (18.4%) responded having land ownership after they had migrated.

7.2.2. State of Personal Savings before and after Migration

The researchers considered savings of money as another important indicator of women empowerment. Consequently, it was found, as shown in Table 2, that

![]()

Table 1. Respondents’ ownership of land before and after migration.

![]()

Table 2. Respondents’ state of savings before and after migration.

personal savings of the respondents increased after migration. When 26.5% of the respondents had saved money before migration, 47.1% were able to save money after migration.

7.2.3. Respondents’ Engagement in Income-Earning Activities before and after Migration

The research shows that all the respondents were engaged in income-earning activities after migration whereas only 40.4% of the respondents earned before migration (Table 3).

7.2.4. Respondents’ Capability to Spend Earned Money before and after Migration

Table 4 shows a positive change in the respondents’ capability to spend earned money. It was noticed that more women (46.3%) were capable of spending their earned money after they migrated to the major city whereas only 33.1% reported to have such capability when they were living in their villages before migration.

7.2.5. Respondents’ Decision Regarding the Expenditure of Loan Money before and after Migration

Table 5 shows the influence of migration on the women’s ability to decide about the expenditure of loan money. It was observed that the economic condition of the respondents changed in a positive manner after they had migrated. Before migration 36 women, who make up 26.4% of the total respondents, were

![]()

Table 3. Respondents’ engagement in income-earning activities before and after migration.

![]()

Table 4. Respondents’ capability to spend earned money before and after migration.

![]()

Table 5. Respondents’ decision regarding the expenditure of loan money before and after migration.

receiving small loans from different local NGOs to carry on income generating activities. Clearly, all of these women became involved in regular paid work in the garment factory following migration; hence only 8.8% reported to have taken such loan after migration. Interestingly however, only a small percentage (17.6%) out of the 26.4% women receiving pre-migration loan responded to have been directly involved in handling or spending the loan money. In contrast, out of the 8.8% of the total respondents with a post-migration loan, 7.3% reported to be making decisions about how to spend that money.

7.2.6. Respondents’ Decision Regarding Receiving Health Care before and after Migration

Table 6 shows the influence of internal migration on the respondents’ ability to make decisions regarding receiving health care services. It can be observed from the table that a positive change took place in terms of the women’s involvement in making such important decisions.

7.2.7. Respondents’ Decision Regarding Having Sex before and after Migration

The study attempted to get a comparative picture of the women’s position or capability of having a say with regard to the nature or frequency of sexual intercourses with their husbands between the times when they used to live in villages and when they had been living in the city following migration. Table 7 depicts the numerical picture of the women’s pre and post migration experience. In fact, more than half of the respondents (52.2%) were not eager to answer the question about their sexual activity. The limited responses however, show a positive change on this indicator following the women’s internal migration.

7.2.8. Respondents’ Exposure and Engagement in the Social Media before and after Migration

Table 8 shows the rate of social media exposure before and after migration among the women. It was observed that 83.1% of the total respondents were engaged in social media activities after migration whereas only 31.6% were active in the social media before migration. Post migration amenities and resources available in the city played a vital role to connect women with the social media.

7.2.9. Respondents’ Decision Regarding Political Participation before and after Migration

A total of 45 respondents (33.1%) said that they took decisions regarding civic engagement or political participation (especially about voting in an election) before they migrated. As Table 9 shows, the women’s rate of such participation decreased after they had migrated.

![]()

Table 6. Respondents’ decision regarding receiving health care before and after migration.

![]()

Table 7. Respondents’ decision regarding having sex before and after migration.

![]()

Table 8. Respondents’ engagement in social media exposure before and after migration.

![]()

Table 9. Respondents’ decision regarding political participation before and after migration.

7.2.10. Respondents’ Decision Regarding Buying Heavy Goods for the Family before and after Migration

Almost half of the women (47.1%) are shown in Table 10 to have participated in making decisions about buying very important goods for the family after they had started life in the city; whereas a much lower number of women (31.6%)

![]()

Table 10. Respondents’ decision regarding buying heavy goods for the family before and after migration.

used to make such decisions before migration. Thus it can be concluded that that Table 10 also shows a positive picture of empowerment among the study participants.

7.2.11. Respondents’ Decision Regarding Movement outside the House before and after Migration

Table 11 also reflects an optimistic picture of the women’s empowerment status following migration as less than 10% respondents said they had enjoyed the freedom of movement outside their homestead when they were living in the village. On the other hand, 47.8% of the respondents could freely move outside of their current home in the city where they had migrated.

7.2.12. Respondents’ Decision Regarding Receiving Health Care for Children before and after Migration

The state of taking decisions regarding receiving health care for children among the women before and after migration is shown in Table 12. It can be observed that before migration 34.6% of the total respondents made a decision when their children needed health care services whereas after migration, 51.5% respondents took a decision regarding meeting the health care needs of their children. This indicates an increase in women’s decision making power in their post-migration life when it comes to receiving health care for their children.

8. Discussion

This study examined the influence of internal migration on women’s empowerment in the capital city of Bangladesh. The survey results found an increase in the respondents’ performance on all the indicators of women’s empowerment, including a post-migration change in increased ownership of land. Women garment workers saved money to buy land in partnership with their husbands in their respective villages. As they were able to contribute to the family income following migration, they have acquired the rights to ownership of the land

![]()

Table 11. Respondents’ decision regarding movement outside the house before and after migration.

![]()

Table 12. Respondents’ decision regarding receiving health care of children before and after migration.

bought by their family. The state and amount of personal savings also increased after migration. Respondents generally reported that they were able to save a portion of their earnings since both husband and wife had been engaged in income-earning activities. Some of the respondents said that a higher income generated by both husband and wife led to a surplus amount after all the monthly expenditure whereas some others had to prioritize savings by putting aside a portion of their income and then managing the family expenses with the rest of the amount. The survey found that only 40.4% of the respondents had been engaged in income-earning activity before they migrated whereas everyone in the sample was found to be involved in paid labor after migration. Those who earned money prior to migration said that they had received money by raising goats and poultries and by cultivating different kinds of vegetables in rural areas. Some of the respondents worked as day laborers in agricultural fields; some others worked as maids in households of the rural elites. The researchers observed that before migration some of the respondents used to earn smaller incomes through different agrarian and household activities with little or no job security and guaranteed wages. But the situation became less precarious after migration as they started making livings from the job sector with a higher security of earning a minimum or fixed amount of money. Furthermore, their capability of spending the earned money was observed to have increased after the migration (33.1% before migration compared to 46.3% after migration). They were pleased to say that they could generally spend as they wished. They spent on not only foods and other items to meet basic needs but also on more fancy materials such as expensive dresses and ornaments.

On the scale of expenditure of loan, it was perceived that the rate of borrowing money actually decreased over time since migration (26.4% before migration and 8.8% after migration). Most of the respondents, who took a loan, said that they did so for meeting some family crises. More interestingly, some of the respondents said that they had to migrate or move to the city in search of a job mainly for the purpose of loan repayment. Similar findings indicated improved status in the area of post-migration decision making ability among the respondents for receiving health care for themselves and their families. The respondents reported in the survey that lately they took such decisions independently. On the other hand, when they lived in villages they were much more dependent on their male family members to take health care related decisions because of their overall dependent status and more conservative cultural practices in the rural areas. But after migration, the situation changed considerably as they could now take their health care in their own hands. Moreover, it has been observed in the study that the state of the decision making about conjugal sexual activity has changed in a positive manner. Most respondents acknowledged that they enjoyed more freedom about sexual involvement with their husbands especially after migration.

Similarly, migration has played a vital role in increasing women’s engagement in the social media. Most of the respondents (83.1%) answers showed that they became increasingly connected and engaged in the social media after migration. They stated that their current work environment facilitated their social media engagement; especially the peer groups in workplaces play a vital role in motivating women to engage in some form of social media. On the other hand, political participation among the respondents was noted to have decreased following migration. The respondents said that they did not usually go back to their villages to exercise voting rights because it would incur a huge cost. Some of the respondents thought they would have exercised their voting power if they could afford to manage the transportation and other relevant cost to visit their constituencies during major elections. But unfortunately most of the times they cannot afford to visit their villages especially simply for the purpose of voting. However, the number of respondents who participated in the decision-making process of buying heavy goods for the family increased after migration as compared to the number of respondents involved in the process before their migration. They thought that as they started earning money and contributing to family welfare, they can now play a vital role in such decision making process. Respondents’ decision making ability regarding movement outside the house has also increased after migration. They said there is usually no barriers to going outside in the public space as their work regularly make them go outside home. Contrarily, when they were living in a village they were confined in the private space of their house due to more restrictive and conservative cultures in those areas. At the present time and environment of a busy metropolitan city where they have migrated and adjusted themselves, they can move around much more freely outside their residence. Accordingly the degree of their decision-making power regarding maintaining children’s health and wellbeing has increased after migration. Thus the respondents have been found to feel empowered in almost all the above mentioned fields with respect to exercising more freedom, choices and independence in making some major decisions in their lives after they migrated to a major urban city and found ways to ensure an income for themselves and their families.

9. Conclusion

Women empowerment is an important issue in the present world, especially in a not so advanced country like Bangladesh, where a large number of women are still marginalized. Many factors contribute to women’s empowerment. In this study, the researchers have considered migration as a major factor of women’s empowerment through examining the status of a random sample of women on different indicators of empowerment such as ownership of land, engagement in income-earning activities, decision-making about buying/selling land, participation in decisions regarding expenditure of loan money, decisions regarding expenditure of earned money including buying heavy goods for family, taking care of children, accessing health care, sexual autonomy, media/social media exposure, political participation, freedom of movement outside house. Comparisons have been made before and after migration with regards to the levels and degrees of such participation and engagement in activities in all of these areas or indicators. The researchers found that all the indicators of women empowerment have moved in a positive direction for the participants following their migration, with the only exception of political participation. Respondents became generally empowered after migration, as they became land owners, saved money, engaged not only in income earning activity, but also in spending their earned money, taking decision regarding the expenditure of loan money, personal and children’s health care, autonomy over having consensual sex with their partner, buying heavy goods for family, movement outside of home, and engaging in the social media. Due to the fast growing economy of Bangladesh, a rapid influx of a large number of people has become more common through migration from the periphery to the center. Results of this study indicate that rapid migration of marginalized women can help Bangladesh achieve the fifth goal of sustainable development through gender equality.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the respondents of this study for answering all the questions with patience. Besides, we would like to express our deep sense of gratitude to Md. Abdur Rashid, Md. Raihan Ali and Md. Sohel Rana.