Nonsurgical orthodontic treatment for an adult with skeletal open bite, class III malocclusion and posterior crossbite: A case report ()

1. INTRODUCTION

The frequency of Class III malocclusions varies in different racial groups. In Asians, it ranges from 4% to 14% and the etiology of this condition varies from one to another [1,2]. Usually it is combined with several other abnormalities such as anterior or posterior crossbites, retroclined mandibular incisors, proclined maxillary incisors, and functional slides from centric relation to centric occlusion. Class III malocclusion associated with skeletal anterior open bite pattern in adults can be a challenging orthodontic problem, especially for nonsurgical treatment. Conventionally, several treatment alternatives are available: tooth extraction, molar intrusion, and absolute anchorage system [3,4] or orthognathic surgical correction [5,6]. Although correction with surgery may be the most effective and stable, many patients refused surgical treatment plan because of the costs and trauma it brings.

The following case report illustrates a nonsurgical, nonextraction treatment of a patient with Class III malocclusion associated with skeletal anterior open bite, posterior crossbite and a high mandibular plane angle. Because he refused surgery and extraction, the only mean we could use was molars intrusion. We used nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve and anterior vertical elastics to correct skeletal anterior open bite and obtained a functional and esthetic result.

2. CASE REPORT

The patient was a 22-year-old male with a convex profile and a moderate increased lower facial height (Figure 1). His chief complaint was anterior open bite. There were no significant findings in his medical and dental histories. The patient had complete dentition without third molars. Clinical evaluation indicated a dental Class III pattern on both sides and a midline shift of the maxilla by 1.5 mm to the left. Skeletal anterior open bite was approximately 5 mm. There was only about 3.0 mm of crowding in both

Figure 1. Pretreatment facial images. (A): the frontal view; (B): the frontal smile view; (C): the profile. The patient was a 22- year-old male with a convex profile and a moderate increased lower facial height. His chief complaint was anterior open bite.

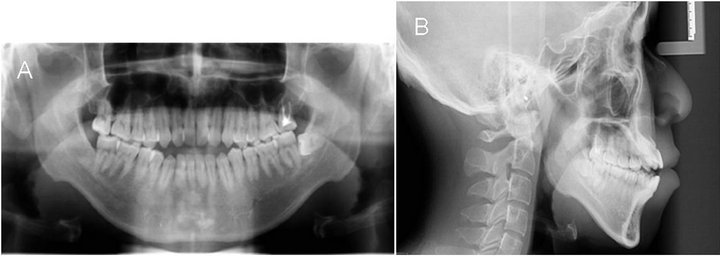

the maxillary and mandibular arches (Figure 2). He denied ever having had any temporomandibular joint dysfunction signs or symptoms, and maximal opening and lateral and anterior movements were within normal limits. Also there were no deviations on opening and closure, and no joint sounds. The panoramic radiograph showed a complete dentition with the mandibular left third molar present and impacted. The condyles appeared normal in size and form. Dental root length and bone height were normal. Cephalometric analysis confirmed the skeletal anterior open bite (mandibular plane angle 50˚) and the dental Class III pattern, skeletal Class I pattern (SNA angle 80˚, SNB angle 77˚, ANB angle 3˚) with most values being normal except the following, U1 to NA 33˚, Interincisal angle 105˚, OP to SN 22˚, GoGn to SN 48.5˚, FMA 50˚, FMIA 40˚, Lower lip to E-plane 6mm. (Figure 3).

The treatment objectives were to create an ideal overbite and overjet relationship and a harmonious maxillary and mandibular arches width, and obtain Class I canine and molar relationships. In this case, establishment of proper overbite and overjet relationships for improved function and esthetics were of most importance for this patient. For the first stage, the goal of treatment was to expand maxillary arch to match the mandibular arch. Thus posterior crossbite could be corrected. During the second stage, the goal was to create an ideal overbite and overjet relationship and Class I canine and molar relationships, which would be obtained by Class III elastics. Also in this stage, reverse curve of the nickel-titanium wire combined with anterior vertical elastics was used to help with molars intrusion to create an ideal overbite relationship. In the third stage, the goal was to maintain the improvement gained in the first and second stages, and to achieve a functional occlusion.

Two alternatives were presented to the patient: The first treatment option was an orthognathic surgery therapy. This treatment includes bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy (BSSRO), counter-clockwise rotation and reduction genioplasty. Its treatment effects include creating an ideal anterior overbite and overjet relationship, harmonious maxillary and mandibular arches width and

Figure 2. Pretreatment intraoral records. (A) to (E), Indicated a dental Class III pattern on both sides, posterior crossbite and a midline shift of the maxilla by 1.5 mm to the left. Anterior open bite was approximately 5 mm. There was about 3.0 - 4.0 mm of crowding in both the maxillary and mandibular arches.

Figure 3. Pretreatment panoramic and cephalometric radiograph. (A): The panoramic radiograph showed a complete dentition with the mandibular left third molar present and impacted. Dental root length and bone height were normal; (B): Cephalometric analysis confirmed the high mandibular plane angle and the skeletal anterior open bite.

Class I canine and molar relationships. Also it could obtain a proper lower facial height. But it costs too much and brings risks. The second alternative was a nonsurgical, nonextraction orthodontic treatment in which Class III elastics and nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve combined with anterior vertical elastics will be used for camouflage treatment. This treatment could produce almost same effects as the first treatment except the proper lower facial height. The ease of the procedure and the expected decent treatment effects of the second treatment led the patient to choose this option.

After obtaining informed consent, treatment began by bonding both arches with 0.022- × 0.028-inch standard edgewise brackets and fixing rapid palatal expansion appliance. Initial leveling was accomplished in 5 months with from 0.012-inch to 0.018-inch round nickel-titanium wires, during which time maxilla expansion was also accomplished by quad-helix. As the maxillary and mandibular arches were leveled and the maxilla was expanded, we used transpalatal arch to retain the maxillary intermolar width and 0.45 mm stainless steel wires for Class III elastics (5/16, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif). The midline deviation was corrected by applying asymmetrical elastics. After achieving a Class I canines and molars relationship, 0.019- × 0.025-inch nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve and tip-back bends was used continuously with anterior vertical elastics to correct open bite. Nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve could intrude not only the posterior teeth but also the anterior teeth. To balance the intrusion effect of anterior teeth, anterior vertical elastics were used in parallel. Thus only posterior teeth were intruded and anterior teeth were left unmoved. Reverse curve of the nickel-titanium wire could also help with molars intrusion and effective molars intrusion could help counterclockwise rotation of mandible, and correction the anterior open bite without excessive elongation of the anterior teeth. At the same time, short Class III elastics were also used on both sides to retain Class I relationship, also it could help achieve a functional occlusion. After 21 months of active treatment, all the treatment objectives were achieved. An overbite of 2.0 mm and an overjet of 3.0 mm were established. Posterior crossbite was also corrected. The dental midlines were coincident with each other and the facial midline (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6). But the lower facial height was not improved because it was only a nonsurgical camouflage treatment. The maxillary and mandibular vertical skeletal relationship was remained uncorrected. The cephalometric analysis showed an increase of interincisal angle (from 105˚ to 118˚). The U1 to NA angle and L1 to NB angle were also improved slightly

Figure 4. Posttreatment facial images (A): the frontal view; (B): the frontal smile view; (C): the profile.The lower facial height was not improved because it was only a nonsurgical camouflage treatment. The maxillary and mandibular vertical skeletal relationship was remained uncorrected. But, the final smile was improved.

Figure 5. Posttreatment intraoral records. (A) to (E), Indicated ClassⅠmolars and canines relationships, with well-aligned teeth and a satisfactory functional occlusion. An overbite of 2.0 mm and an overjet of 3.0 mm were established. Posterior crossbite was also corrected. The dental midlines were coincident with each other and the facial midline.

Figure 6. Posttreatment panoramic and cephalometric radiograph. (A): the mandibular left impacted third molar was extracted. Dental root length and bone height were normal; (B): The cephalometric analysis showed an increase of interincisal angle, but the lower facial height was not improved.

after treatment (U1 to NA angle, from 33˚ to 27˚, L1 to NB angle, from 37˚ to 30.5˚). But the FMA angle did not improve significantly after treatment (from 50˚ to 47˚). The temporomandibular joints were asymptomatic, and the patient was satisfied with the functional and esthetic results.

3. DISCUSSION

Malocclusions involving skeletal anterior open bite usually occur in patients with high mandibular plane angles and increased lower facial height. Much has been written in the orthodontic and surgical literatures about the diagnosis and treatment of skeletal open bites related to the “long-face syndrome” patients [7-9]. Even so, the cause of anterior skeletal open bite has not been established definitively [10], it may be related to reduced posterior facial height, hyperdivergent growth pattern, clockwise or backward rotation of the mandible, and the resultant excessive anterior lower facial heigh [9,11]. Planning different treatments for patients in different ages and stages of craniofacial and dental development is essential to success. Therapies include modification of functional or habitual aberrations, orthopedic treatment, orthognathic surgery, and orthodontic treatment with extrusion of the anterior teeth or intrusion of the posterior teeth [12]. In the actively growing and compliant patient, removable or fixed functional appliances should be used for guiding maxillary and mandibular growth to reduce treatment time and produce a more balanced denture and face [13-15]. In adult patients, orthognathic surgery therapy should be the first choice because it is most effective and stable [16-18] and provides significant improvement in both occlusion and facial esthetics. Nonsurgical camouflage treatment should only be adapted to patients who do not wish to undergo surgical treatment because of its risks and the clinician must weigh carefully the benefits and costs of this choice [19,20]. As far as this patient is concerned, he refused extraction, not to speak of surgery. So the only effective means we could use was molars intrusion. We used nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve combined with anterior vertical elastics to intrude upper and lower molars. This intrusive application could produce a force distal to the center of resistance of the dentition, thus a clockwise moment at the maxillary dentition and a counterclockwise moment at the mandibular dentition occurred. These movements were effective in closing the anterior open bite [12]. In addition, small vertical changes in the posterior teeth area can produce profound changes in the anterior area. Only1 mm intrusion at the posterior teeth can produce about 3 to 4 mm upward movement of the chin [12,21]. This stage lasted nearly 10 months and we obtained an ideal overbite relationship. Implant anchorage can only produce an innermaxillary molar intrusive force and could not make maxilla clockwise and mandible counterclockwise rotate. Anterior open bite closing mainly depends on elongation of the anterior teeth and intrusion of posterior teeth. Nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve combined with anterior vertical elastics can produce an intermaxillary force to rotate maxilla and mandible and a molar intrusive force to intrude molars. So, it is more effective than implant anchorage in treating anterior open bite. Also this patient had skeletal Class I, dental Class III malocclusion and posterior crossbite. Class III elastics and quad-helix could correct these abnormalities easily. Patient cooperation throughout the treatment was of great importance because nickel-titanium wire with reverse curve could worsen the anterior open bite without anterior vertical elastics. So it should be used carefully and only for compliant patients.

4. CONCLUSION

The key to success in treating skeletal anterior open bite with nonsurgical, nonextraction orthodontic means is the proper use of archwires and elastics to intrude upper and lower molars Nicaction or implant anchorage. Patients could easily accept it. In this case, no adverse response to treatment occurred, and the patient obtained satisfactory occlusal, functional, and stable results.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the patient for allowing the publication of this case report. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. We also thank Associate Professor Jinwu Chen for performing the panoramic and cephalometric radiography.

NOTES