Designing a Pronunciation Self-Assessment Checklist for Aircraft Engineering Technology Students in an ESL Higher Education Context ()

1. Introduction

The aim of this study was to design a pedagogical tool for Bachelor of Aircraft Engineering Technology (BAET) students in an ESL environment in a private university in Malaysia. The rationale for the study relates to the importance of pronunciation in international communication generally and in the aviation industry in particular, as well as the students’ needs, the university’s intended role as an Approved Training Organisation for aviation maintenance, and gaps in the literature. In many settings of international communication, pronunciation is not only more important than is widely acknowledged but is “the foundation of messaging” (Pennington and Rogerson-Revell, 2019: p. 1) . Within the aviation industry, the requirement for comprehensible pronunciation mentioned by Moder (2014) is associated with maximising safety in both non-routine and routine situations. This requirement has been extended from pilots and Air Traffic Controllers to aircraft maintenance technicians following research findings which found that limited English on the part of an aircraft maintenance technician or inspector was responsible for between four and ten incidents a year; inadequate verbal English ability was identified as one of the main causes (Drury et al., 2005) .

BAET graduates mostly take up careers as aircraft maintenance technicians in multinational teams in the aviation industry where clear pronunciation in English is highly important because safety is a paramount concern. Aircraft maintenance technicians are expected to achieve a specified level of spoken English proficiency on the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) scale (ICAO, 2010) . BAET students therefore take an Aviation English course embedded in their degree. The course lasts 2 hours a week for 18 weeks and covers a full syllabus which allows insufficient time for work specifically on pronunciation. Moreover, a diversity of first languages among Malaysians, as well as variable quality in English teaching in primary and secondary schools (Rashid et al., 2017) , means that individual difficulties and needs for improvement in pronunciation can vary considerably among students.

The university where the research was conducted is a listed Approved Training Organisation for aviation maintenance and, as such, is required to carry out assessments of English language proficiency (DCAM, 2014) . Aircraft maintenance personnel must provide evidence of English language proficiency which is acceptable to the Civil Aviation Authority (CAAM, 2021) . Additionally, classroom experience has shown that many BAET students have experienced difficulties in becoming more independent learners, after the university’s introduction of problem-based learning in line with the country’s goal of developing students as independent learners with an interest in lifelong learning, the university has adopted problem-based learning. It is acknowledged that self-assessment can help to develop skills that are useful for both problem-based learning and lifelong learning, namely reflection and metacognitive monitoring (Yan & Brown, 2017) .

There has been increasing use of formative self-assessment in the language learning classroom for some time, using self-assessment as a tool for learning and teaching rather than for measurement of performance (Butler, 2023) . However, self-assessment of pronunciation has been less well investigated than other forms of assessment of pronunciation (Isaacs & Harding, 2017) . Research into formative self-assessment of pronunciation has mainly investigated reliability and accuracy. Reliability has typically been in terms of correlations between teacher assessment and self-assessment, sometimes along with peer assessment (e.g. Dlaska & Krekeler, 2008; Hua, 2023 ). Accuracy and awareness have typically been explored using comparisons between recordings of a learner and a model, which could be, for example, a native speaker model (e.g. Dlaska & Krekeler, 2008 ) a trained phonetician (e.g. Hua, 2023 ), or student comparisons of phonetic transcriptions of the model with their transcriptions of their own pronunciation (Cojo Guatame, 2019) . Measures of accuracy and awareness have included numbers of errors detected as well as closeness to native speaker model. Some studies have focused on how learners assess themselves, that is the processes of self-assessment rather than the product (e.g. Gralińska-Brawata, 2022; Jankowska & Zielińska, 2015 ).

The decision to focus on the process of self-assessment rather than outputs and measurement in the present study was influenced by the lack of familiarity with, and experience of, self-assessment among many of the students and some of the teachers at the research site. Moreover, self-assessment is generally related to awareness-raising activities which involve students in judging their own performance with the goal of improving their learning outcomes (Harris & Brown, 2018) . The majority of learners are not aware of their pronunciation problems and those who can identify their problems tend to focus on particular individual sounds (Derwing & Rossiter, 2003) . It was therefore considered appropriate to raise students’ awareness of their learning strategies, which could assist them with preventing mistakes as well as correcting mistakes after they occurred. What was needed was a pedagogical tool to support teachers as well as students in developing their understanding and practice of the self-assessment process. A preliminary search for an existing checklist failed to yield a suitable pedagogical tool, highlighting the need to design and develop a context-specific checklist for the students in the target population.

2. Objectives and Research Questions

The specific objective of the initial phase of this study was to design a self-assessment checklist for use as a pedagogical tool to help Bachelor of Aircraft Engineering Technology (BAET) students to develop their understanding of how to self-assess their pronunciation. Following the design and trialling of the pedagogical tool, usefulness would be evaluated in terms of its reliability, construct validity, impact and practicality. In order to achieve the design objective, the first phase addressed the following research question:

· What criteria should be used to design the student pronunciation self-assessment checklist?

It was considered important to involve students and teachers early in the process so that they could comment on the clarity of the items and the feasibility of using the checklist.

3. Literature Review

The literature review sought to establish the conceptual foundations of the checklist through examination of key relevant literature in the fields of self-assessment checklists, metacognition, pronunciation, and language learning strategies.

3.1. Self-Assessment

Self-assessment is understood in a variety of ways so it is important to clarify that it is operationalised in this study as formative assessment for learning, generating feedback from students to themselves to promote learning and improvement, rather than determining or contributing to their final grades (Andrade & Valtcheva, 2009) . This suits the purpose of assisting students to develop their understanding of self-assessment. Moreover, when students complete a task using self-assessment, it is important to create a feedback-feed forward loop by making improvements the next time they perform a similar task. This includes students’ enquiry into their own learning habits and strategies in terms of their English pronunciation as well as identification of areas for improvement. Reference to criteria and standards is included in the pedagogical tool in order to provide students with guidance on what they are aiming for; students welcome such guidance and find self-assessment easier when they are clear about what was expected of them (Andrade & Valtcheva, 2009) .

3.2. Metacognition Theory

Various theories underpin self-assessment, including constructivist theories of learning and motivation, metacognition theory, self-efficacy and self-regulation theory. Whilst there are ongoing debates about the nature and definition of metacognition, there is broad consensus that a person uses metacognition to decide which cognitive strategies to use in a specific task, and the success of those strategies feeds back to the metacognitive level where changes of strategy are considered for the next similar task. Thus, there are typically three stages or components in a metacognitive cycle, namely planning, monitoring and evaluation (Muijs & Bokhove, 2020) .

Metacognition theory is strongly associated with self-efficacy, self-regulation and reflection (Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009) , and with formative self-assessment (Jessner, 2018) . Interest and use of metacognitive strategies in language teaching and learning, such as identifying opportunities to practise, paying attention, and monitoring production, has increased notably in recent years (Haukås, 2018) . It is recognised that speaking places particular demands on the use of metacognitive strategies (Zhang et al., 2022) . Increasing students’ awareness of their metacognitive processes and strategies should therefore assist them to improve their pronunciation as a part of speaking.

3.3. Pronunciation

Various options for operationalising the construct of pronunciation were examined, beginning with the segmental phonology and suprasegmental phonology of pronunciation (Pennington & Rogerson-Revell, 2019) . It remains unclear whether teaching segmentals or suprasegmentals is more likely to enhance pronunciation (Wang, 2020) . In the light of most BAET students having studied English for 11 years and having diverse L1 backgrounds, and thus likely to have differing individual needs for improvement of segmentals, suprasegmental features were selected as more appropriate for the pedagogical tool.

Consideration was given to the nativeness and intelligibility principles (Levis, 2020) . Since air maintenance technicians are highly likely to work in multinational teams with diverse L1 backgrounds and accents, accentedness was prioritised over native like pronunciation. Intelligibility is defined in terms of actual understanding of pronunciation and the ease with which understanding occurs (Levis, 2020) , with the emphasis in the present research context more on the speaker’s control of their pronunciation than on the listener’s ease of understanding. From the listener’s perspective, other elements of speech may be needed for ease of understanding, such as vocabulary, grammar and fluency, but the first essential in communication is clear pronunciation (Pennington & Rogerson-Revell, 2019) .

A search of the literature for how pronunciation was operationalised revealed a scarcity of scales and descriptors appropriate to suprasegmentals in the literature, other than those in high-stakes English tests. Hence, the operationalisation of pronunciation in selected high-stakes tests was examined, as well as in the Common European Framework of Reference for languages (CEFR) self-assessment grids and the pronunciation subscale of the comprehensibility speaking rubric developed by Isaacs et al. (2018) . None of the scales or descriptors were totally suited to ease of use in the classroom context for a variety of reasons. One reason was that descriptors included wording which was over-dependent on the listener’s interpretation of terms used, such as “full range of phonological features” or “requires some effort”/“requires little effort to understand”. Other reasons were that different aspects of pronunciation were featured in different levels, were mixed with terms more closely related to fluency such as fluidity, pacing, or speech rate and chunking, or were too detailed, as in the CEFR phonological scale (Council of Europe, 2020) . Ultimately, the ICAO rating scale was chosen because it exhibited consistent use of the terms ‘pronunciation, stress, rhythm and intonation’ at all levels and consistent use of frequency measures, thus reducing the complexity of explanation and understanding. Moreover, meeting the ICAO standard is what students work towards and introduction of a different set of criteria might have adversely affected their motivation.

3.4. Language Learning Strategies

Learning strategies have been linked with metacognition in language learning (Anderson, 2008; Oxford, 1990) . Anderson (2008) has suggested that teachers can train students to choose, use, combine, monitor and evaluate their use of learning strategies. Oxford (1990) identified three groups of learning strategies as metacognitive strategies within her overall taxonomy: centring learning, such as paying attention and noticing; arranging and planning learning, for example, setting clear goals and looking for opportunities to work towards achieving them; and evaluating learning by reflecting on progress. The few cognitive strategies relevant to learning pronunciation related to practising sounds, oral repetition of new words, and trying to emulate native English speaker pronunciation.

Some researchers have focused specifically on pronunciation learning strategies (e.g., Derwing & Rossiter, 2003; Eckstein, 2007; Pawlak & Szyszka, 2018; Peterson, 2000 ). Peterson (2000) conducted an exploratory qualitative study of strategies with beginner, intermediate and advanced adult learners of Spanish. Study participants were 11 adult learners of Spanish who were native English speakers; levels in Spanish ranged from beginner through intermediate to advanced. Six students kept a diary recording every strategy they were using, or had previously used, in learning pronunciation. Diary data were analysed and strategies identified were added to others found in reviewing the literature. Three students, one from each level, were then interviewed about their use of pronunciation learning strategies; the list compiled from the diaries was used to prompt for clarification or encourage further thought. Strategies categorised as metacognitive were: finding out about target language pronunciation, setting goals and objectives, planning for a language task, and self-evaluating. Selecting specific sounds as a learning goal, and recording and listening to oneself as a method of self-evaluation were also included. The researcher’s review of Peterson’s (2000) language learning strategies highlighted some potentially useful verbs and items for a pronunciation self-assessment checklist such as “noticing”, “practising”, and “I look up the pronunciation of new words in a dictionary”.

The Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ) (Vandergrift et al., 2006) . The MALQ was based on literature related to learning strategies and metacognition as well as items and formats found in existing instruments that assessed strategy use in listening and reading comprehension. A list of items was submitted to two rounds of expert judgement and piloted with several students to ensure clarity, after which exploratory factor analysis, field testing and confirmatory factor analysis were employed to determine and validate the remaining items. The final version of the MALQ contained 21 items that included error detection and directed attention and covered three stages of “before listening”, “as I listen”, and “after listening”. The stages were not however arranged sequentially; like Oxford’s Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) (Oxford, 1990) , the questionnaire was designed to assess a learner’s typical use of strategies rather than to focus on their use of strategies in a specific task.

The (MALQ) has been adapted for speaking, in a questionnaire that includes three items related specifically to pronunciation, one for adjusting pronunciation errors while speaking, one for evaluating their speaking and subsequently trying to practise differently, and one for imitating spoken material (Sulistyowati et al., 2022) . Both the listening and speaking versions influenced the design of items in the pronunciation self-assessment checklist.

Studies examining metacognition have adopted a variety of methods, to elicit students’ thinking about their learning strategies, including retrospective think-aloud protocols after a task, completion of learning logs or diaries, and completion of inventories of metacognitive awareness or learning strategies. However, these were not practical in view of the time constraints of the research setting. Checklists offer another way to help students to become more aware of their thinking processes (Rowlands, 2007) . The term “checklist”, as used in the classroom setting, includes rubrics and scripts featuring a variety of formats (Andrade, 2019) .

3.5. Self-Assessment Checklists

Decisions about the design criteria of a checklist are important to achieving its purpose. These decisions are likely to be influenced by the classroom context: the constraints of curriculum and timetable, the level of learners, how long they have been learning and using the language, whether they are studying in an ESL environment, and whether or not they are English or Linguistics majors. Design choices are likely to reflect the preferred pedagogical approach of the researchers, teachers, or institutions involved. Although these decisions may be made on the basis of teaching experience and knowledge of learners, they need to be defensible. Hence a variety of studies were critically examined to assess their theoretical foundations as well as their practical implications. While no checklist or study was found which could readily be adapted to match the needs of the BAET students at the research site, inspiration was provided by a checklist that brought together the elements of the metacognitive cycle of self-assessment, as well as students’ awareness of what they should do and why they should do it (Nimehchisalem et al., 2014) . This argumentative writing checklist aimed to raise awareness of what students needed to before they attempted a writing task, while executing the task, and while checking after completion of the task. However, this design needed adaptation for use with pronunciation, because there is less time to think about a spoken task due to the intensity of focus on producing the next idea or sentence in real time. An extended guide supported students to be more independent in their learning by proposing methods of achieving the checklist criteria in settings outside of the classroom. The extended guide covering what a student should do and why do it was adapted as a separate document accompanying the checklist for BAET students.

A 5-point Likert scale was chosen for responses because of its simplicity, reliability and widespread use in academic settings (Dörnyei, 2003) . Frequency of use was measured from “almost always” to “almost never” in order to avoid the obvious polar opposites of “always” and “never” which, it has been suggested (Wyatt & Meyers, 1987) , can lead to a narrower range of responses. A mid-point of “sometimes” was included because the scale concerned frequency of individual actions rather than opinion. Using a 4-point scale would have created a forced choice for students who would genuinely wish to respond “sometimes” rather than “rarely” or “often” to their use of particular learning strategies. Likert scales referring to “true of me” (Oxford, 1990) or “agree/disagree” (Vandergrift et al., 2006) were avoided because they may suggest that the scale relates to a personal trait or personal opinion rather than focusing attention on a learning behaviour which may be more adaptable.

4. Methodology

The overall methodology was development research, which typically has three or four phases in the development of a context-specific pedagogical tool (Richey & Klein, 2005) . The three phases in the full study were design, calibration and evaluation. The phase described here is the initial design phase, and this section presents the steps involved, participants, design criteria, methods of data collection, and analysis.

4.1. Design Phase

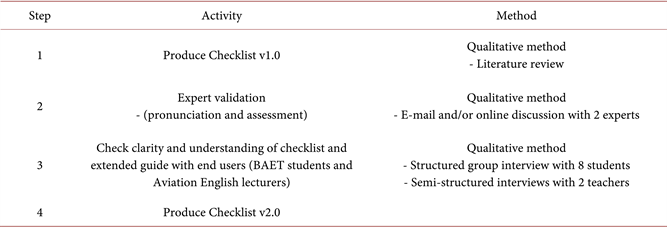

The first version of the checklist, which was accompanied by a separate extended guide, was designed based on the review of available literature on pronunciation, self-assessment checklists, metacognition, and language learning strategies. This was followed by expert validation in addition to comments on the clarity and understanding of the checklist from students and teachers. After careful consideration of all comments, changes were made to the checklist at the end of the design phase. The four distinct steps in the design phase are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Steps in design phase.

4.2. Participants

Participants in development research typically include some combination of designers, developers, students, teachers, and experts (Richey et al., 2004) . Participants in development research typically include some combination of designers, developers, students, teachers, and experts (Richey et al., 2004: p. 1115) . This can be considered a particular case of what Creswell terms purposeful sampling in which the inclusion criteria are defined according to who can best assist the researcher to understand “the central phenomenon” being explored (Creswell, 2014: p. 76) . This study used purposive sampling to invite 5 Aviation English teachers, in addition to the researcher, and 50BAET students from a private university in Malaysia as the participants in the design, trialling and evaluation of the checklist. Two of the teachers responded positively and were involved throughout the study. All the students came from three classes of the teachers and the researcher. Demographic information showed that a representative range of English proficiency was present in all three classes. All were in their first year, 8 in the second semester and 42, who had previously completed a diploma, in the fourth semester. All were aged between 18 and 20 years old, 40 were male and 10 female, and the vast majority were Malaysian. Eight of the students were involved in the design phase. The experts involved in this phase were established experts in the area of assessment, with particular experience of high stakes assessment using the ICAO rating scale.

4.3. Instruments

In terms of the instruments used in this phase of the study, in addition to the checklist and extended guide, interview guides were used in semi-structured interviews with the two participating teachers and in the structured group discussion with eight students. The checklist and extended guide were thoroughly discussed, item by item and in general, with two Aviation English teachers using a semi-structured interview schedule. They were also examined by the eight BAET students who took part in the structured group interview. At the start of the interview, participants were encouraged to consider their own views of self-assessment by selecting one of three statements (presented in Section 5) that best reflected their own opinion of self-assessment.

4.4. Data Collection

Qualitative Methods

The checklist and extended guide were emailed to two experts with particular knowledge and experience of the ICAO rating scale. The experts were specifically asked to comment on the clarity and completeness of the checklist and extended guide, paying particular attention to the construct of pronunciation. Semi-structured interviews were held with two teachers and a structured group interview was conducted with eight students. A teacher colleague took notes during the structured group interview in order to add to the trustworthiness of the data collection. Interview guides were prepared for both types of interview and were designed to elicit participants’ views of self-assessment as well as to gather comments on the clarity and ordering of checklist items along with comments on the extended guide. All participants had the opportunity to see the interview questions, checklist and extended guide before the interviews so that they knew what to expect and could spend some time thinking about the materials. The amended version of the checklist is shown in the Appendix.

4.5. Data Analysis

Data collected from the structured group interview and semi-structured interviews were recorded and transcribed before analysis. The data were analysed qualitatively, based on development of codes allocated to one of three broad categories: checklist review (structured by interview questions asked about clarity, relevance and ordering of items, sections and extended guide), theory (metacognition and self-assessment), and data-driven codes (teachers’ and students’ understandings of self-assessment and their own roles in the process).

5. Results

This section presents and discusses the changes made to the checklist following comments from experts, students and teachers. It also highlights other important considerations arising from the interviews and structured group discussion. Gathering comments from the different sources contributed a fruitful range of perspectives that required careful and critical consideration. The contributions from the experts are presented first, followed by the contributions from the end-users (teachers and students). Some of the proposed changes were accepted while others were rejected. The main changes made were the removal of redundant words and the incorporation of extended guide into appropriate sections of the checklist. Decisions were based on the purpose of the checklist, supporting literature, and on the design principles of clarity of wording and feasibility of use.

The experts proposed that the instructions at the beginning of the checklist should directly address students, so that “The objective of this checklist is for students to…” should be replaced by “This checklist is to help you assess your own pronunciation” and other instructions should be similarly amended. This suggestion was adopted, as was the amendment of an item “I pronounce the words clearly in English” to read “I try to pronounce each and every word clearly in English”. The researcher agreed that using the word “try” would give average or weaker level students more opportunities to feel included and encouraged in the process of completing the self-assessment checklist. The item “I self-correct my pronunciation during the presentation” was refined to “I self-correct my pronunciation whenever I mispronounce”. Expert comment highlighted that students could only self-correct if they knew their pronunciation was wrong and it would be impossible to self-correct if they were unaware it was wrong; the change was therefore made by the researcher.

However, a suggestion that the past tense should be used throughout the checklist if it was to be used for self-assessment purposes, perhaps assuming that self-assessment should take place only after an activity was complete, was rejected. Section A (the “before” section) was designed for use while students were preparing for a speaking activity, and the use of the present tense in Section B (the “during” section) was designed to make the experience feel immediate again, reliving the experience and helping to promote reflection-in-action. The original choice of tenses was justified based on examples in the literature (Oxford, 1990; Vandergrift et al., 2006) and therefore the use of the present tense was maintained.

A major concern raised by the experts concerned the use of technical language and assessment standards. On one level, the terms “stress”, “rhythm” and “intonation” were said to need more written explanation describing what the terms meant. This concern was considered at length but ultimately rejected on the basis that the literature states that teaching these technical elements of English requires practical examples, exercises and practice (e.g., Levis & McCrocklin, 2018 ). Accordingly, this concern was addressed by expanding the researcher’s briefing session for students to include explanations and examples of the technical terms.

One expert questioned whether there should be more guidance for Section B (“During the speaking activity”), noting its absence, without suggesting what guidance might be needed. No action was taken by the researcher at this stage because it was considered that, in contrast to sections A and C (Before and After the speaking activity) when students had time to practise beforehand and reflect afterwards, they would be unlikely to refer to the extended guide for section B during their speaking activity; at best this would be challenging and distracting for the students, and it is highly unlikely they would be able or willing to use it. Finally, a suggestion to include a description of the extended guide itself in the introduction to the checklist was addressed by the inclusion of the extended guide in the checklist, as proposed by the teachers and students.

The positioning of the extended guide was discussed by participants. Some thought all the extended guide should come first so that students could see the bigger picture, understand the idea of doing the assessment, and increase the probability of students using it. Others proposed each section of the extended guide should be placed before the section to which it referred, so that students could concentrate section by section. The researcher’s experience of teaching BAET students supported the proposal to place each section of the extended guide immediately before the checklist section to which it referred. The revised version of the checklist shown in the Appendix titled the sections simply as “guidance”. The decision to place the extended guide just before the section to which it referred was supported by the use of Google Forms, which required consideration of clarity and length of page content and an optimal balance of content on different pages. The students’ comments were very helpful regarding the layout and use of Google Forms; they had more experience of using Google Forms than the teachers or researcher.

The majority of changes related to ensuring the clarity and readability of the checklist, the instructions, items and extended guide. Teachers suggested that instructions would be better given in bullet form because students are used to this, and the researcher duly changed the instructions from sentences in paragraph to bullet point format. This format is recommended in Web accessibility guidelines (Accessibility Guidelines Working Group, 2022) . Moreover, using a format familiar to students would help to keep their focus on pronunciation self-assessment rather than running the risk of the layout distracting them.

Suggestions which improved the readability of the checklist were accepted. To reduce redundant words in agreement with Accessibility Guidelines Working Group (2022) , the researcher removed phrases from items in Sections A, B and C and replaced them with an introductory phrase, as proposed by teachers and consistent with readability guidelines such as those in the Australian government Style Manual (n.d.) (https://www.stylemanual.gov.au/). The original and revised versions of items in Section A are shown in Table 2.

Students and teachers both thought that the concept of pronunciation as specified in the checklist was complete, without unnecessary words or items. Teachers confirmed that “we would usually focus on the intonation and then all of the criteria that you have mentioned…we do not need like extra questions or extra criteria” (Teacher 2), while students commented more generally; for example, “I think about the content is well-chosen, very focused on few specific things about self-assessment” (Student 2). Teachers expressed concern about whether students would understand or remember the terms: “I know the stress is to be like this for example but the student might think that the stress is different” (Teacher 1). The

![]()

Table 2. Removal of redundant phrases in Section A of checklist.

same teacher added “if…we use this regularly every time they want to do any speaking activities, we give them this, maybe they will understand, maybe they can remember enough, in other words”. As one student expressed it, “we need to see the bigger picture first” (Student 8). These comments highlighted the issues of explanation, shared understanding of assessment criteria, and repetition and reminders of criteria, all of which needed to be taken into account in trialling, and later implementing, the checklist.

All participants were happy with the number and order of sections; typical responses were “For the section is nice and perfect” (Student 6) and “The amount of questions in each section is perfect, not too much, it’s just the right amount” (Student 5), and were supported by several other students. Similarly, students were satisfied with the number of items and their clarity, as illustrated by “the questions are all very straightforward, and simple, compact and just perfect” (Student 5), although teachers suggested streamlining them as shown in Table 2.

The contributions of teachers and students as end users of the checklist were important to ensuring its feasibility. Whilst teachers were more critical of the wording and order of items, they had not used Google Forms, which is where the students were quick to suggest the importance of layout, minimising the need to scroll up and down, and making sure the amount of information on each page was neither too much nor too little.

One student also suggested that administering the checklist during a class would be more effective than sending the link separately, “because some people may get annoyed because there so many questions and just tick, tick, tick and you will not get accurate information” (S6). The researcher and teachers agreed with administration in class from the perspective that this would ensure students completed the checklist.

Turning to existing perceptions of self-assessment, students and teachers were asked to choose one of the following three statements which best represented their personal view of self-assessment.

1) Self-assessment helps students to become independent learners; this is a useful skill that can help them in their careers in the future.

2) Self-assessment may or may not be helpful or necessary, depending on how it is used and if there is enough time to do it.

3) Self-assessment is not necessary; teachers provide all the assessment that students need.

Five of the eight students chose statement 1, while three chose statement 2; no students chose the third option. The main reasons for choosing the first option were that students needed to be independent learners, that they knew themselves and their strengths and weaknesses better than anyone else, and that they needed the skills of self-assessment in their future careers and life. From the perspective of developing independent learning, one stated:

“It is nice to have their teachers or lecturers to help them doing the self-assessment, but at the same time you know yourself best and you know your weaknesses and you know how to strengthen yourself” (Student 5).

Some students made a connection between taking responsibility for their own learning and developing their professional competence when they entered the world of work. One student recognised that self-assessment skills could assist with making the transition to employment and went even further, suggesting that knowing oneself could improve relationships with other people:

“It’s really different, in the classroom and with the outside world. The situation is really different so with the self-assessment that they receive in the classroom they can use in the future to help them to improve their skills towards the other human being outside there. Not only to our teachers, but to others person” (Student 7).

The three students who chose the second statement explained that they needed lecturers to help them identify what they should improve, and that some students would not understand without help. Student 1 for example stated:

“As a student, our job is to learn, and we need guidance to learn and that’s where the lecturer’s role comes in, you know... because students doing self-assessment may not be accurate because sometimes we don’t know where we did wrong” (Student 1).

Another student recognised the broad spread of ability within a class:

“Sometimes some students understand and some students not understand because it hard. That’s all” (Student 6).

The spread of ability, knowledge and confidence was exemplified in the contrasting ways in which students referred to the checklist, some repeatedly referring to it as a questionnaire even after being gently corrected, some searching for the correct word, and others confidently referring to it as a checklist.

In contrast to students who commented that they knew themselves better than anyone else, one student commented “I don’t [self-assess] during and after because I don’t know myself” (Student 8).

The teachers were divided in their opinions, one choosing the first statement and one choosing the second. However, the teacher who chose the first option had not tried to use self-assessment with students, but instead had “a sort of discussion…when they are listening to my lecture…sometimes we do talk about that” (Teacher 2). The other teacher felt that students would not notice what a teacher would notice and always gave feedback after a speaking assessment to tell students what they had done well and what their mistakes were. These comments informed the initial briefing session that the researcher delivered to all three classes, ensuring a good explanation of the terms “rhythm”, “stress”, and “intonation”.

Students also valued the explanation of the ICAO scale and its descriptors, as illustrated by the following comments:

“It’s really like, amazing, because when you see this checklist, you get to see and you feel that English is actually very important and the fact you have to meet up with this language proficiency rating scale. I understand how much like English is important” (Student 5).

“It’s very thoughtful to have that scale” (Student 8).

This view was supported by other students who mentioned that they needed to improve their pronunciation in terms of their career in the aviation industry because it could be dangerous if they say a particular word but a work colleague hears it as a different word.

6. Discussion

The design of the present checklist reflects the need for students to be more independent in learning pronunciation, in agreement with Pawlak and Szyszka (2018) and Sardegna (2022) . In contrast to studies which focus on self-assessment instruments, such as Jankowska and Zielińska (2015) , or more closely link pronunciation research with teaching methods, such as Sardegna (2022) , the design of the present pedagogical tool is aimed at raising students’ awareness of some of the key components of the self-assessment process. It focuses on raising awareness and understanding of the criteria that students will be expected to achieve, together with awareness of their thinking processes before, during and after a speaking activity, and awareness of learning strategies. The importance of awareness and understanding of criteria has been highlighted by Andrade and Valtcheva (2009) , Yan and Brown (2017) and Yan and Carless (2022) , among others. Particular attention has been drawn to the role of metacognition in language learning by Haukås (2018) , and the potential of language learning strategies has been identified by Pawlak and Szyszka (2018) and Sardegna (2022) . The design of the checklist meets the need to raise students’ awareness identified by Jankowska and Zielińska (2015) , although it will be trialled, with possible fine tuning, and an evaluation of its usefulness, before implementation.

There have been calls for increased involvement of learners in instructional design for many years, but many teachers and learners are not used to implementing this approach, and implementation can prove challenging (Richey & Klein, 2014) . Development research offers a way of involving learners at an early stage, if a more constructivist approach is wanted. From a practical point of view, the present study has shown that teachers’ experience and insights into the classroom context are potentially valuable sources of knowledge that can inform the development of pedagogical tools in the early stages. The same is true of the students’ involvement at an early stage of development in the checklist, and the contributions of students and teachers along with those of experts allowed the three perspectives to be considered together.

7. Conclusion

The checklist in this present study was developed through research but its implementation in the classroom has yet to be addressed. There are important pedagogical implications, starting with the way students are introduced to the purpose of formative self-assessment and the explanation, illustration and discussion of the criteria. Key considerations include teaching students how to apply the criteria, for example by modelling, providing feedback on how the students have understood and completed their self-assessment, and assisting them to use what they learned to make improvements, in addition to ensuring enough time is allowed for reflection (Panadero et al., 2016) . Teachers also need to consider how students could gain useful feedback from external sources, for example peer discussion.

In respect of the theory of self-assessment of pronunciation, the checklist directs attention to the process of self-assessment rather than the outcome. It addresses the lack of pedagogical tools that can stimulate students to think about their learning strategies in specific contexts and to consider alternatives. The availability of multi-media language courses and applications that give feedback on the accuracy of pronunciation does not appeal to every learner as something they can do in their own time. The checklist offers students an opportunity to explore their learning strategies and consider alternatives that might better suit them and the learning goals they want to attain. In this respect it adds to existing initial approaches to formative self-assessment.

Choosing a development research process made it possible to incorporate end users’ views at the earliest possible opportunity, increasing the likelihood that the checklist would be used. However, this type of development research is centred on the development of projects in a particular context, which means that the findings are unlikely to be capable of generalisation, and this may make development research less attractive to many academic research communities. On the other hand, research projects designed to meet a very specific need tend to generate a range of projects which can amount to a considerable body of new knowledge over time. Meanwhile, teachers in similar situations, where EFL is embedded in time-constrained technical courses, may find the checklist useful.

Appendix. Pronunciation Self-Assessment Checklist

Dear Student

This checklist is to help you assess your own pronunciation in English before, during and after a speaking activity based on the ICAO Language Proficiency Rating Scale.

Along the way, you will find guidance to help you complete the checklist.

You may find it useful to read the guidance for each section before completing the section.

Please answer ALL the questions.

1) Name: _______________________________

2) Class: _______

3) Gender: Male ☐ Female☐

4) Latest English examination and result: _____________________________

Guidance 1: Read this to help you understand the ICAO Language Proficiency Rating Scalebetter

LEVEL

PRONUNCIATION

Assumes a dialect and/or accent intelligible to the aeronautical community

VIDEO

Expert 6

Pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation, though possibly influenced by the first language or regional variation, almost never interfere with ease of understanding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VZ6Ll41fIdo

Extended 5

Pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation, though influenced by the first language or regional variation, rarely interfere with ease of understanding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNL4sfG1pF4

Operational 4

Pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation are influenced by the first language or regional variation but only sometimes interfere with ease of understanding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VZ6Ll41fIdo

Pre-operational 3

Pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation are influenced by the first language or regional variation and frequently interfere with ease of understanding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNL4sfG1pF4

Elementary 2

Pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation are heavily influenced by the first language or regional variation and usually interfere with ease of understanding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pb4t0kn9fPk

Pre-elementary 1

Performs at a level below the Elementary level.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4B0Xx03pnc0

Source: Manual on the Implementation of ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements, International Civil Aviation Organization (2004).

Guidance 2: Word Definitions of the important terms from Guidance

1) Syllable is defined as “a word or part of a word usually containing a vowel sound”. For example, “cheese” has one syllable, “but-ter” two and “mar-ga-rine” three (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxQJW7Xj1mU3d4G_H8kuxJJG4h2RwAqQ0R

2) Word stress is whenone (or more than one) syllable in a word will be higher in pitch, longer in duration, and generally a little louder than unstressed syllables. https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkxi6aQB9_AAIpNI1a54WJ4qSUntCqSfdYP

3) Rhythm is the sense of movement in speech, marked by the stress, timing, and quantity of a syllable—word or a part of word that only has one vowel sound. https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkx8GEXE7Ygl76sAJpErJhCx-QSzxOaRVjQ

4) Intonation is the way the pitch of your voice goes up and down as you talk. For example, when you are surprised, we can detect your surprised intonation in your voice. https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkx_iJ3nD0pu-4JZ-jTUBAXh6OoK4Co_gYt

Guidance 3: Read this to help you better understand Section A: Before the Speaking Activity

Item

Why & How

Before the speaking activity:

1) I practise my pronunciation.

Why?

· You will have more confidence during a speaking activity.

How?

· Practise with friends or record yourself.

2) I choose words which I can pronounce easily.

Why?

· This is to ensure your listeners understand you during a speaking activity.

How?

· Check vocabulary and pronunciation options online and choose the easiest for you to pronounce.

3) I check on the pronunciation of difficult words.

Why?

· This is to ensure you will explain clearly and confidently during a speaking activity.

How?

· Online dictionary, pronunciation website and YouTube.

4) I pronounce the words clearly in English.

Why?

· You will be able to correct yourself during a speaking activity.

How?

· Online dictionary, pronunciation website and YouTube

· Practise with your friends, or record yourself

5) I stress the words accurately in English.

6) I speak English with a regular rhythm.

7) I practise speaking English with a natural intonation.

8) I refer to the ICAO Language Proficiency Rating Scale (LPRS) as guidance for my pronunciation for my speaking activities.

Why?

· The ICAO scale is the standard for the aviation industry where you will work when you finish your degree.

How

· Refer to the rating scale and video clips.

SECTION A: Before the Speaking Activity

Please circle (1 - 5) to indicate the frequency level of each criterion according to the key given:

1 = Almost never

2 = Rarely

3 = Sometimes

4 = Often

5 = Almost always

Evaluative criteria

Frequency level

Before the speaking activity:

1) I practise my pronunciation.

1 2 3 4 5

2) I choose words which I can pronounce easily.

1 2 3 4 5

3) I check on the pronunciation of difficult words.

1 2 3 4 5

4) I pronounce the words clearly in English.

1 2 3 4 5

5) I stress the words accurately in English.

1 2 3 4 5

6) I speak English with a regular rhythm.

1 2 3 4 5

7) I practise speaking English with a natural intonation.

1 2 3 4 5

8) I refer to the ICAO Language Proficiency Rating Scale (LPRS) as guidance for my pronunciation for my speaking activities.

1 2 3 4 5

Guidance 4: Use these descriptions for the measurement scale in Section B: During the speaking activity

Frequency

Description

1 = Almost never

You are not careful when pronouncing words during a speaking activity. You can make people understand you anyway, maybe by changing words, or gestures or repeating what you say.

2 = Rarely

You attempt to be careful when pronouncing words during a speaking activity, but not for all the words. It could be only 5 words in a 15-minute speaking activity. The word choice would be based on your preference (e.g., difficulty of pronunciation).

3 = Sometimes

You attempt to be careful when pronouncing words during a speaking activity, but not for all the words. It could be only 30 words in a 15-minute speaking activity. The word choice would be based on your preference (e.g., difficulty of pronunciation).

4 = Often

You are careful when pronouncing as many words as possible throughout a speaking activity, regardless of how difficult they are to pronounce, although you still make mistakes.

5 = Almost always

You are careful when pronouncing almost all the words throughout a speaking activity regardless of how difficult they are to pronounce.

SECTION B: During the speaking activity

Please circle (1 - 5) to indicate the frequency level of each criterion according to the key given.

1 = Almost never

2 = Rarely

3 = Sometimes

4 = Often

5 = Almost always

Evaluative criteria

Frequency level

During the speaking activity:

9) I am careful when pronouncing the words in English

1 2 3 4 5

10) I notice my pronunciation mistakes when I am speaking.

1 2 3 4 5

11) I self-correct my pronunciation whenever I mispronounce.

1 2 3 4 5

12) I try to pronounce each and every word clearly in English.

1 2 3 4 5

13) I stress the words accurately in English.

1 2 3 4 5

14) I pay attention to speaking English with a regular rhythm

1 2 3 4 5

15) I speak English with a natural intonation.

1 2 3 4 5

Guidance 5: Read this to help you better understand Section C: After the Speaking Activity

Item

Why & How

After the speaking activity:

1) I reviewed a recording of my speaking activity for self-improvement.

Why?

· Reviewing a recording helps you to notice your mistakes and correct them.

How?

· Online recording, handphone, tablet or laptop.

2) I listed down the words I mispronounced.

Why?

· This is to avoid repeating the same mistake.

How?

· List down as many mistakes as you can remember as soon as you have finished your speaking activity, or when reviewing your speaking activity recording.

3) I took note of the words that I stressed inaccurately in English.

4) I took note of the words that I spoke with the wrong rhythm.

5) I took note of where my intonation caused problems for my listeners.

6) I listened to correct examples of pronunciation in English.

Why?

· This to ensure you know how the words should be pronounced and give you extra practice before your next speaking activity.

How?

· Repeat your speaking activity in your own time and try to notice and self-correct any mistakes.

7) I practised speaking correctly after listening to examples of pronunciation in English.

SECTION C: After the speaking activity

Please circle (1 - 5) to indicate the frequency level of each criterion according to the key given.

1 = Almost never

2 = Rarely

3 = Sometimes

4 = Often

5 = Almost always

Evaluative criteria

Frequency level

During the speaking activity:

16) I reviewed the recording of my speaking activity for self-improvement.

1 2 3 4 5

17) I listed down the words I mispronounced.

1 2 3 4 5

18) I took note of the words that I stressed inaccurately in English.

1 2 3 4 5

19) I took note of where I spoke with the wrong rhythm.

1 2 3 4 5

20) I took note of where my intonation caused problems for my listeners.

1 2 3 4 5

21) I listened to correct examples of pronunciation in English.

1 2 3 4 5

22) I practised speaking correctly after listening to examples of pronunciation in English.

1 2 3 4 5