Prevalence and Associated Factors of Postpartum Depression: A Study Conducted in Health Centres in Dakar (Senegal) ()

1. Introduction

During pregnancy and childbirth, women are more vulnerable to mental health problems. Postpartum depression is the most common of these disorders. According to the WHO, it affects 10% - 15% of women who have just given birth. This makes it a real public health problem, with often dramatic short and long- term consequences if not properly treated. Postpartum depression can have a negative impact on the mother, the mother-child relationship, the child’s development, and the couple.

Postpartum depression has been the subject of renewed interest among those involved in perinatal care, with the development of tools to facilitate screening and diagnosis. However, it remains an under-diagnosed condition, particularly in developing countries. Studies on the subject show that levels are generally higher in low- and middle-income countries than in developed countries [1] [2] . In Senegal, studies on psychological disorders in pregnancy and childbirth in general have been published [3] . With regard to post-partum depression, we only found the Thiam et al. study, which described the psychopathology [4] . There is no epidemiological data on post-partum depression in Senegal. It is for this reason that we conducted this screening study of post-partum depression in order to assess its characteristics.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Setting

Our study was conducted in the reference health centres of the twelve health districts of the Dakar region (the capital of Senegal). The survey took place in the vaccination units and/or maternity wards of each centre. This choice was made to facilitate recruitment of women who had given birth in the previous six weeks. Under Senegal’s Expanded Programme on Immunisation, newborns receive their first dose of pentavalent vaccine six weeks after birth. Similarly, the postnatal visit to the midwife or gynaecologist is scheduled for 42 days after delivery.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Study Type

This was a prospective, cross-sectional study with descriptive and analytical aims.

2.2.2. Objectives

The main objective of this study was to determine the current status of postpartum depression among new mothers attending health centres in Dakar.

The specific objectives were:

- Measure the prevalence of postpartum depression;

- Determine the socio-demographic characteristics of women giving birth;

- Identify the risk factors for postpartum depression;

- Identify risk factors associated with postpartum depression.

2.2.3. Study Population

Our study targeted women who had given birth in the previous 4 to 6 weeks and were attending health centres in Dakar for vaccination and/or postnatal care. Sampling was done by the non-random convenience method. Participants were selected in order of arrival before their baby’s vaccination or postnatal visit.

2.2.4. Inclusion Criteria

Women were included if:

- aged 18 years and over;

- who had given free and informed consent;

- who had given birth within 4 to 6 weeks and were bringing their child for vaccination and/or for postnatal counselling.

2.2.5. Non-Inclusion Criteria

Women were not included if they were:

- minor;

- did not consent;

- who had given birth less than 4 weeks or more than 6 weeks previously.

2.2.6. Sample Size

The minimum sample size was n = 174. This was calculated using the formula

n = sample size;

t = confidence level according to the reduced centred normal distribution (1.96 for 95% confidence);

p = estimated proportion of the population with the characteristic under study, according to the literature (13%, corresponding to Ethiopia);

m = tolerated margin of error (set at 5%).

2.2.7. Investigator

The survey was carried out by a single investigator who visited the different health centres in Dakar consecutively.

2.2.8. Duration of the Study

The study lasted from August 2021 to June 2022. One week of working days was allocated to each health centre, usually from Monday to Friday, from 8.30 am to 2 pm.

2.2.9. Ethical Considerations

Before starting the research, we submitted a file containing the research protocol and the informed consent and information forms to the National Committee on Ethics in Health Research (CNERS) at the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, which gave a favourable opinion. Participation was voluntary. After reading a form containing all the necessary information, free and informed consent was obtained from each participant by means of a form before the interview began. It was also explained that she had the right to stop the interview at any time. In addition, participants with a score of 10 or more were informed about the mental health resources available to help them get the help they needed. Finally, the data collected were archived with an anonymity code assigned to each participant to ensure confidentiality.

2.2.10. Survey Instruments

The study was conducted using two questionnaires.

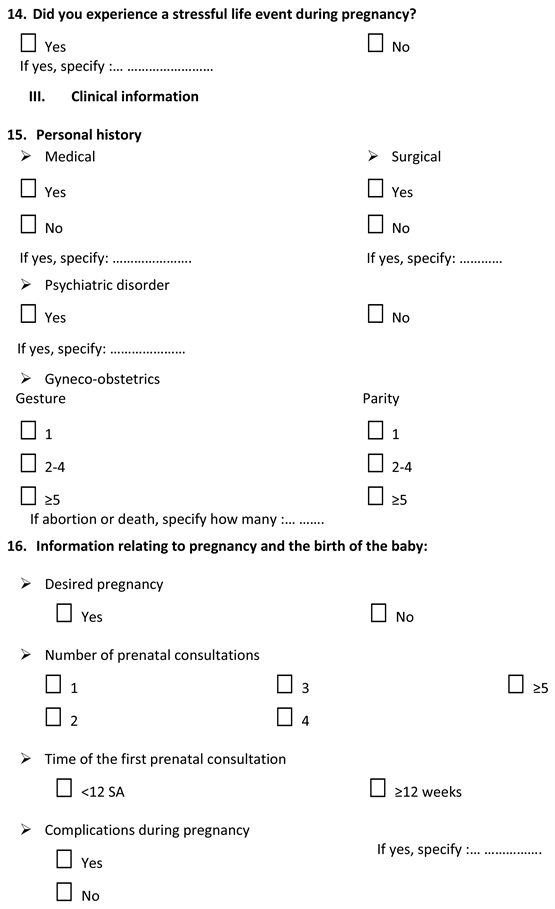

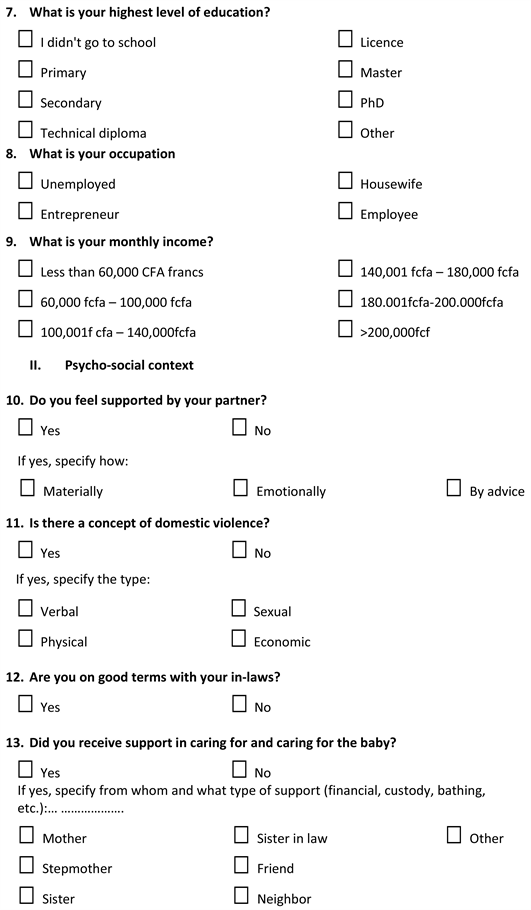

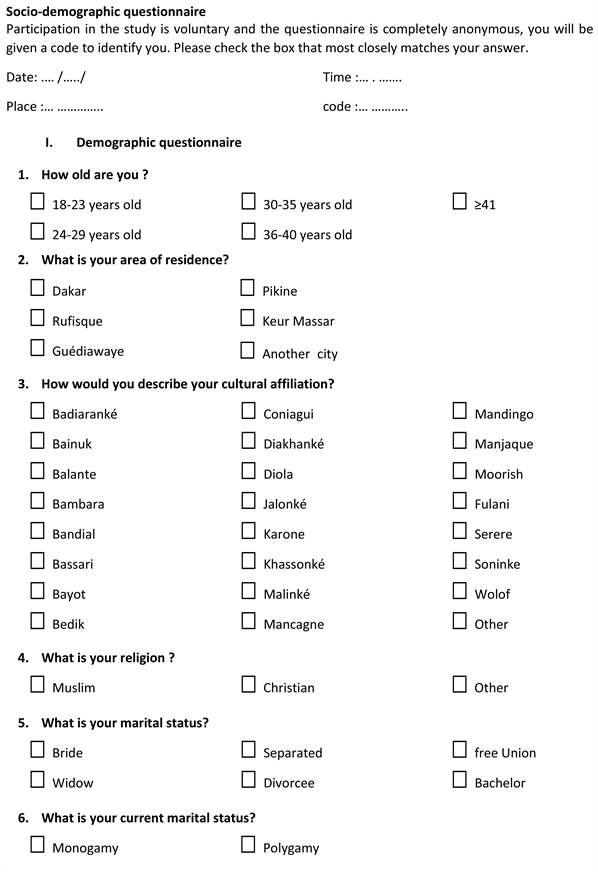

The first questionnaire (see Appendix), which we carried out ourselves, focused on the participant’s socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, with the following variables:

- Age, area of residence, cultural background, religion, marital status and regime, level of education, socio-professional occupation, monthly income;

- Level of social support: spousal support, whether or not there has been domestic violence, tension with in-laws, support in caring for the baby and the occurrence of a recent significant event;

- Clinical data: existence of chronic illnesses, personal and family history of psychiatric pathology, gestational age and parity;

- Pregnancy and infant data: desire to become pregnant, term of pregnancy, satisfaction with pregnancy monitoring, method of delivery, birth weight, sex of baby desired or not, state of health and breastfeeding method.

The second questionnaire is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale developed by Cox [5] . This is an internationally recognised psychometric tool and the most widely used to screen for postpartum depression. The questionnaire is simple and quick to administer. Its acceptability to patients makes it a tool of choice. It consists of a series of 10 questions with 4 possible answers per question, scored 0, 1, 2 or 3. We used the French version by Guedeney, validated in 1998, with a positivity threshold of 10.5, a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 92% on a prevalence basis of 13% [6] (see Appendix).

The two questionnaires were previously tested on five patients.

2.2.11. Data Collection and Management

Microsoft Excel was used to collect and classify data. Descriptive analysis was carried out using Excel. Statistical analysis was performed using Epi-info version 7.2.6 and R version 4.2.3. The X2 test and multiple logistic regression were used to determine the associations between the different variables and the occurrence of postnatal depression in the participants. Associations were considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence (See Table 1)

At the end of our survey, we recruited one hundred and twenty-two (122) participants with a prevalence of PPD of 25.41%.

3.2. Sociodemographic Aspects (See Table 2 and Table 3)

The most represented age group was 24 - 29 years (n = 44). The majority of participants (36%, n = 44) lived in the district of Pikine. All women were of urban origin. The most represented ethnic group was the Fulani (40%), followed by the Wolof (25%) and the Serer (16%). The majority of the participants were Muslim (97%). Most participants were married (93%) and 79% of them were polygamous. The enrolment rate for women was 88%, with a predominance of secondary (36%) and primary (35%) education. In terms of employment, 54% of women were unemployed, 34.43% were entrepreneurs and 11.48% were employees. The majority (33%) of women received less than 98.45 US$ (60.000 FCFA) per month. Only 18% (n = 21) had a monthly income of more than 295.34 US$ (180.000 FCFA).

3.3. Psychosocial Context

9% of women did not feel supported by their partner during pregnancy and postpartum. Domestic violence was present in 14% of couples (see Table 4).

![]()

Table 1. Prevalence of postnatal depression in Dakar health centres (N = 122).

![]()

![]()

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (N = 122).

![]()

Table 3. Distribution of participants by health district.

![]()

Table 4. Breakdown by domestic violence (N = 122).

Verbal violence was experienced by 13% of women, physical violence by 7% and economic violence by 4%. Non-consensual sex occurred in 2% of women. In terms of the wider family environment, 22% of women had disagreements with their parents-in-law.

When it came to help with caring for the baby, 22% of the women had no help at all. For those who did, the most common source of support was the participant’s mother (22%), followed by their sister-in-law (15%). 28% of the women had experienced a stressful life event during pregnancy. Of these, 56% had been affected by the death or illness of someone close to them.

3.4. Clinical History

22% (n = 27) of the participants had a chronic disease (see Figure 1). Hypertension was the most common chronic disease (55.17%). A quarter of the women (25%) had undergone surgery. The most common type of surgery was one or more caesarean sections (81.26%). Only 1% of the participants reported a personal psychiatric history. However, 5% of the participants reported the presence of a person with psychiatric pathology in their immediate family. The majority of women (55%) had had between 2 and 4 pregnancies and parities.

![]()

Figure 1. Distribution by medical history (N = 122).

3.5. Course of Pregnancy

The pregnancy was unintended in 17% of participants (see Table 5). 95% of women had at least 3 antenatal consultations (ANC). The majority (73%) of the first ANCs took place before the 12th week of amenorrhoea. A complication occurred during pregnancy in 12% of cases.

Regarding the quality of antenatal care, 6% of women were not satisfied and 2% did not feel supported by the caregivers. 4% of participants felt mistreated during their pregnancy, either by their family or by health professionals. 51% of women had never received antenatal care. Of those who had, 46% had been prepared by their nurse at their last antenatal visit.

93% of deliveries were at term, compared with 2% preterm and 5% post term. Most deliveries (82%) were vaginal. Birth weight was normal in 93% of cases. However, 2% had low birth weight and 5% were macrosomic.

Most babies were female (53%). A quarter of participants said they had no preference about the sex of their baby, while 23% wanted a child of a different sex.

In our series, 2% of the babies had a disease: anaemia under investigation, trisomy 21 and malnutrition. 68% of the women breastfed exclusively, 30% breastfed in combination with formula milk and 2% gave only formula milk or had started to diversify their diet with paps.

3.6. Factors Associated with Postpartum Depression (See Table 6 and Table 7)

Firstly, after entering and processing the database using Microsoft Excel, we carried out a bivariate analysis using simple logistic regression. This allowed us to divide the variables into two groups: those with a p-value greater than 0.25 and those with a p-value less than 0.25. A significant association was found between postnatal depression and the following factors:

Ø Sociodemographic: Single marital status was more likely to cause postpartum depression, with a rate of 100%;

Ø Psychosocial:

- Lack of partner support, with 50% of women experiencing postpartum depression;

- Domestic violence: almost 53% of victims developed postpartum depression, with a p-value of 0.0013;

![]()

Table 5. Breakdown by desire for pregnancy (N = 122).

![]()

Table 6. Summary of the determinants of postpartum depression.

![]()

Table 7. Risk factors associated with the onset of post-partum depression.

- Conflict with in-laws was highly significant with a p-value of zero;

- Experiencing a significant event during pregnancy;

Ø Clinical: the presence of a personal medical history;

Ø Related to the course of the pregnancy:

- Lack of satisfaction with antenatal care;

- Caesarean section.

However, we found no association between the onset of postpartum depression and age, religious affiliation, educational level, socio-professional activity, monthly income, history of psychiatric disorder, gestational age, parity, parity, birth weight, sex of intended or unintended child, type of breastfeeding, or with a family history of psychiatric pathology.

Secondly, multivariate regression was performed using the top-down method. A first model was used in which all variables had a p-value of less than 0.25. We then examined the effect of each variable with a p-value greater than 0.25 on our first model. We then examined the effect of each variable with a p-value greater than 0.25 on our first model. Variables that improved our model were retained for further regression. Based on this new model, we used the likelihood test to successively remove the variables that did not have an impact on the model, based on the insignificance of the p-value of the likelihood test. In this way, we obtain a final model with only the variables that have an impact on it, as shown in Table 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence

The results obtained do not allow us to generalise them to the Senegalese population as a whole. However, our study revealed the existence of postnatal depression with a prevalence of 25.41% (n = 31) according to the EPDS with a threshold score greater than or equal to ten (≥10). We did not find a similar study in Senegal to assess the variation of this prevalence in our country.

Our results are in line with those of many studies carried out in Africa. Indeed, the prevalence of postnatal depression was 23% in Nigeria [7] , 25% in Ethiopia [8] and 23.4% in Cameroon [9] . This similarity could be explained by the fact that the EPDS was used in all these studies with populations of a fairly similar overall socio-economic level. Similarly, a study conducted in France found a prevalence of 25.5% [10] .

However, our prevalence is higher than that of O’Hara’s meta-analysis in the United States (13%) [11] and that of a study conducted in Canada (17.5%) [12] . The sample sizes in these studies were generally larger. However, they were lower than those found in Uganda (43%) [13] , Lagos (35.6%) [14] , Morocco (39%) [15] and South Africa (50.3%) [16] .

In sum, differences in prevalence between these studies and ours may be due to differences in study design, the postpartum period at which the study was conducted (some go as far back as 6 months), differences in geographical location, as well as the cut-off score of the screening instrument used.

Overall, we noted an increase in the figures over time, with rates appearing higher in developing countries [17] . This is the result of a combination of factors, the main one being low socio-economic levels, but also urbanisation and individualisation, which affect so-called developing societies. In view of these different prevalences, PPD is a real public health problem.

4.2. Factors Associated with PPD

4.2.1. Socio-Demographic Factors

A statistically significant association (p = 0.008) was found between single marital status and the occurrence of postnatal depression among our participants. These findings confirm previous studies conducted in Cameroon [18] , Jamaica [19] , Uganda [9] and South Africa [16] .

This can be explained, firstly, by the difficulty of experiencing pregnancy alone, without the moral/financial support of a partner. Secondly, they run a number of risks by carrying a pregnancy to term in a social environment where the majority of pregnancies are only conceived within marriage. As this is considered unacceptable in the Senegalese socio-cultural context, these women may be subject to stigmatisation, abuse and ostracism, or even expulsion from the home. Being single is an additional factor of vulnerability and increases the risk of postnatal depression, especially if these women have no family support.

In our study, dissatisfaction in the relationship with the spouse was a determining factor in the occurrence of PPD among the participants (p = 0.002 - 0.006). This association is found in most studies in the African literature: in Nigeria [14] , Cameroon [9] , Ethiopia [20] and South Africa [16] . This can be explained by the fact that a quality marital relationship reduces the risk of psychological vulnerability, which is the breeding ground for peripartum psychological decompensation. It strengthens a new mother’s ability to adapt to parenthood. What’s more, the new status of mother requires certain resources and adjustments which, if they cannot be made, can lead to a lack of self-esteem, which in turn can lead to depression. So, in addition to the stress of childbirth, women may be vulnerable to PPD because of a lack of support, love, affection and advice from their partner. In addition, the gendered division of care and housework within a couple has been identified as a key factor in women’s depression [21] .

Domestic violence was present in 14% of couples. This high rate is lower than the 56.96% found in a study conducted in Dakar with 253 participants [22] . This difference could be partly due to the fact that we did not assess psychological violence in our study.

In addition, domestic violence was significantly associated with postnatal depression in our analysis. This finding is similar to that of Adeyemo in Nigeria [14] and Toru in Ethiopia [23] . Furthermore, a meta-analysis shows that exposure to domestic violence is a factor in mental disorders in women [24] . Domestic violence is considered a major risk factor for relationship vulnerability; it undermines a woman’s integrity and therefore has a negative impact on her mood, which is the starting point for postnatal depression.

We found an association between disagreement with in-laws and the onset of PPD (p = 0.00). As worded, this item was not found in our readings. Instead, it referred to conflict within the family itself, as in a study in Oman [25] .

In our study, there was a highly significant association between the occurrence of a stressful life event during pregnancy and the onset of postpartum depression (p ≤ 0.001). These events could be the death of a close relative, serious illness, marital conflict, divorce, financial problems, etc. This result is similar to that found in studies conducted in Uganda [13] , Morocco [15] and Saudi Arabia [26] . It is also the most common factor found in meta-analyses [27] .

4.2.2. Clinical Factors

1) Medical history

In our study, there was an association between the presence of a chronic maternal illness and the occurrence of PPD. This is consistent with a study conducted in Nigeria [14] . In addition to their physical effects, chronic diseases have a strong depressogenic potential. Thus, the addition of illness in the stressful context of postpartum could strongly induce postnatal depression.

Furthermore, neither gestational age nor parity had any influence on the occurrence of PPD in our participants. This is in line with some meta-analyses [27] [28] . However, other studies have reported a significant association with multiparity [14] [29] and with previous abortion [8] .

Only one participant in our series reported a history of depression. It is therefore difficult to assess the results of the association tests, which showed no link. As mentioned previously, personal psychiatric history is one of the most common factors in postnatal depression. Most prevalence and factor studies and meta-analyses report that the postpartum period is considered to be at high risk of psychological decompensation [15] [16] . Indeed, in a Canadian study, there was a significant association between a personal history of baby blues and depression and the occurrence of PPD [12] . Women who had already experienced the baby blues or postnatal depression during previous pregnancies were at greater risk of suffering from them again. Finally, 5% of our participants reported the existence of a psychiatric disorder in a close relative, but we found no association with the occurrence of PPD, unlike a study in Ethiopia [30] .

2) Factors related to pregnancy and childbirth

Wanting to become pregnant, the occurrence of complications, maltreatment and preparation for childbirth, and the length of pregnancy were not statistically associated with the occurrence of PPD in our study. Other studies have instead found an association with lack of planning and unwanted pregnancies [16] [23] . Prematurity, which is not a predictor of PPD in our study, was associated with PPD in Asaye’s study in Ethiopia [8] . Health centres are mainly attended by women and babies who appear to be healthy. Premature babies are vaccinated later than other babies because they spend more time in the neonatal unit. This may explain the low proportion of preterm births in our series and limit the interpretation of results in relation to gestational age.

6% of participants reported dissatisfaction with the way their pregnancy was managed. They reported a lack of attention and answers to their concerns during their antenatal visits or during the birth. This factor was strongly associated with the development of postnatal depression in our study (p-value <0.001). In fact, dissatisfied participants were 26 times more likely to develop PPD. This rate of dissatisfaction, although not negligible, was lower than that found in a study of obstetric care at the Hospital Social hygiene institute de Dakar, where 13% reported having had a poor experience of antenatal care [31] . Other studies have reported similar results in Morocco [15] and Ethiopia [30] , as has a meta-analysis [32] .

Caesarean section was associated with the occurrence of postnatal depression in our study. This confirms the findings of several authors, especially in Nigeria [14] , Ethiopia [30] , Morocco [15] , Saudi Arabia [26] and Argentina [29] . This is one of the most controversial factors, as the results vary widely depending on the methodology used. Some argue that it is more relevant to assess the context in which the procedure was performed (illness, obstetric complications) and the prognosis for the foetus [27] . An unfavourable outcome with disease or even sequelae in the newborn and/or the new mother seems to be the real factor in PPD.

3) Baby-related factors

In our analysis, we found no association between factors specifically related to the baby and postnatal depression.

For example, the presence of a malformation or illness in the baby was not associated with postnatal depression. Only three of the one hundred and twenty-two women reported a condition in their baby, including chronic anaemia, malnutrition and trisomy 21. This could be due to selection bias in the mother-child units of the health centres, which tend to be attended by women and children who appear to be in good health.

In some studies conducted in France [33] and Nigeria [34] , health problems and/or adjustment difficulties in the child were associated with PND. The caveat with this factor is that the direction of the association is difficult to determine. It is recognised that constant crying and a child in poorer health may contribute to or exacerbate depression, as in a vicious cycle.

In addition, low birth weight [8] and disappointment at the announcement of the baby’s sex [13] [15] were factors found in studies in Nigeria and Morocco. Non-exclusive breastfeeding [14] [29] and difficulty feeding the baby [6] were also implicated in the occurrence of postnatal depression.

4.3. Constraints and Limitations

The study was conducted at a time when there were untimely strikes by health workers, which affected vaccination activities and women’s postnatal care. This reduced the size of the sample. In addition, another non-negligible source of bias was the selection of women only from vaccination units or postnatal visits at health centres. This means that we recruited almost exclusively women who had been pregnant and who had generally received non-pathological postnatal care. Women who give birth prematurely or with complications are monitored by a gynaecologist and their babies are admitted to the neonatal unit a little late for the vaccination schedule.

5. Conclusion

Post-partum depression is a common but largely under-diagnosed condition, especially in low-income countries. It has serious consequences for the mother, the mother-child bond, the child’s development, the couple and the rest of the family circle. Our study showed a high prevalence of PPD (25.41%) and identified associated risk factors. Eight of these factors were decisive in the occurrence of PPD: single marital status, lack of spousal support, domestic violence, conflict with in-laws, stressful life event during pregnancy, personal medical history, dissatisfaction with pregnancy follow-up, caesarean delivery. Systematic screening or identification of risk factors during pregnancy is necessary for compréhensives treatment based on a bio-psycho-social approach.

Annexes

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

Date:

Anonymity Code:

You just had a baby. We would like to know how you are feeling. We kindly ask you to complete this questionnaire, highlighting the answer which you think best describes how you felt during the week (i.e. over the 7 days which have just passed) and not only at today’s day:

here is an example

· I felt happy:

Yes all the time

Yes, most of the time

No, not very often

No not at all.

This will mean “I felt happy most of the time during the past week”. Please answer any other questions.

DURING THE PAST WEEK

1. I was able to laugh and take things on the positive side:

As often as usual

Not quite as much

Really much less often these days

Absolutely not

2. I felt confident and joyful, thinking about the future:

As much as usual

Rather less than usual

Really less than usual

Almost not

3. blamed myself, without reason, for being responsible when things went wrong:

Yes, most of the time

Yes sometimes

Not very often

No never

4. I felt worried or worried without reason:

No not at all

Almost never

Yes sometimes

Yes, very often

5. I felt scared or panicked for no real reason:

Yes, really often

Yes sometimes

No, not very often

No not at all

6. I tended to feel overwhelmed by events:

Yes, most of the time I felt unable to cope with situations

Yes, sometimes I haven’t felt as able to cope as usual

No, I was able to deal with most situations

No, I felt as efficient as usual

7. I felt so unhappy that I had trouble sleeping:

Yes, most of the time

Yes sometimes

Not very often

No not at all

8. I felt sad or unhappy:

Yes, most of the time

Yes, very often

Not very often

No not at all

9. I felt so unhappy that I cried:

Yes, most of the time

Yes, very often

Only from time to time

No never

10. I have had thoughts of harming myself:

Yes, very often

Sometimes

Almost never

Never