Corporate Social Responsibility and Pro-Environmental Behaviors of Mining Companies: A Case of Newmont Mining Company ()

1. Background to the Study

Climate change is a global issue with its consequences piercing through national borders and affecting lives and societies (Barrow, 1999) . The headway to addressing climate change is largely multi-sectorial requiring corporations to revisit the perception of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and its influence in improving individual level pro-environmental behaviors. The Ghanaian studies on CSR have largely found that the dimension of CSR practiced by organizations in Ghana is predominantly philanthropic with little emphasis of organisations on ethical and social dimensions (Amo-Mensah & Tench, 2015) . Even though there are evidences of influence of corporations on environmental issues, there is little evidence on the relationship between perception of CSR and pro-environmental behaviors in Newmont Mining Company in Ghana, hence this necessitates the present study.

The competitive business environment today demands that corporations implore strategic initiatives to achieve corporate social license for their long-term survival. The quest to win corporate legitimacy in the sight of stakeholders has caused many corporations to consider their corporate social responsibility as the competitive edge to win publics approval for their operations (May, Cheney, & Roper, 2007) . Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as of its beginning was largely influenced by the thoughts of Friedman (1970) who opined that corporation’s main responsibility to the stakeholders is the profit making. In other words, the main focus of CSR from Friedman’s point of view was largely economic responsibility. This position on CSR championed by Friedman was interrogated in the 1980s by Freeman’s conception of the social dimension of CSR (Freeman, 1984) . Freeman considered the operation of corporations to be towards contributing to general societal good. The economic versus social dichotomy of CSR championed by Friedman and Freeman respectively contributed to the building of the understanding CSR as beyond a profit-making initiative to include a social capital initiative (Afsar & Umrani, 2019; Fieseler, 2011) .

In expanding the responsibilities of corporations to stakeholders, the work of John Elkington famously termed the Triple Bottom Line redefined the CRS dimension to cover three main areas, thus profit, planet and people (Amo-Mesnah & Tench, 2018) . In his perspective, Elkington (1998) argues that corporations are supposed to be responsible in the making of profit, protection of people and maintenance of the environment. The debate on CSR was therefore, changed from the dominant economic dimension to the inclusion of ethical, social and discretionary dimension. In these multi-pronged dimensions of CSR, Carroll (1999) in redefining of the field of CSR brought to light the ethical, philanthropic, economic and social dimensions of CSR. Though Carroll (1999) offered one of the most accepted definitions of CSR, the European Commission (2011) cited in (Amo-Mensah & Tench, 2018) expanded his definition by conceptualizing corporate social responsibility as “a practice which corporations undertake to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders” (p. 681). This definition opens addition of the environmental responsibility of CSR answers Willard (2002) cited in May, Cheney, & Roper, (2007) who questioned the absence of “environmental” in the CSR set as a drawback in the conceptualizing of CSR as largely social rather than environmental.

The call for environmental responsibility of corporation is louder today than ever because of the rising climate change situation in the world today. May, Cheney and Roper (2007) observed that CSR communication encapsulates a communicative practice, which corporations undertake to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders. The environmental bit is gaining attention because of the need for collaborative efforts among stakeholders to address the issue of Carbon dioxide emissions and other environmental hazards which are affecting the environment health negatively, and indirectly ecosystem and human life. The environmental communicator, Barrow (1999) argued that the Fordism era which was marked by line production and profit-making industrial revolution is gradually giving way for post-Fordism era which is characterized by the eco-ecology where economic interest must be balanced with environmental concerns.

The extension of corporate social responsibility to address environmental concerns posed by corporations is partly due to the Okerekel, Wittneben, and Bowen (2012) who sourced that in May 2011, the International Energy Agency (IEA) announced that global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from energy use in 2010 reached its highest in history. At 30.2 Giga tons (Gt), energy-related CO2 emissions rose by 5% from the previous record year in 2008 when emissions reached 29.3 Gt. This threat calls for economic development to bolster innovation, clean technology, green investment, adaptation, and ultimately to achieve climate protection. The role of international organizations, governments and stakeholders in environmental matters are calling on businesses to behave in an environmentally friendly manner.

2. Statement of Problem

The environmental and social concerns have awakened stakeholders to demand justification for environmental and social actions of corporations. This phenomenon is termed as corporate legitimacy. Corporate legitimacy is the generalized perception that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions (Nielsen & Thomsen, 2018) . This expectation has made corporations more aware of their responsibilities towards the environment now than before. This has informed the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors to meet the environmental responsibility (Raza, Farrukh, Iqbal, Farhan, & Wu, 2021) . The adoption of pro-environmental behavior as part of CSR activities of corporations is vital in changing the CSR narrative in Ghana to favor climate change management strategies as discovered in other jurisdictions (Raza et al., 2021) . Even though synthesis of literature of CSR in Ghana from 2006 to 2018 (Damoah, Peprah, & Cobla, 2019; Amo-Mensah & Tench, 2015; Damoah et al., 2019; Ansu-Mensah et al., 2021) revealed that the philanthropic and ethical dimension of CSR are given more attention by corporations than no environmental dimension. Meanwhile, studies in Ghana have discovered negative environmental practices by corporations ( Amo-Mensah & Tench, 2015; Damoah et al., 2019; Ansu-Mensah et al. 2021; etc.), there is little evidence on CSR perception and pro-environmental behaviors of corporate entities in Ghana. This study explores leaders’ and employees’ perception of CSR and its relationship with their pro-environmental behaviors.

3. Aim and Objective

There is no doubt that the government and media campaign against illegal mining, dubbed #Stop GalamseyNow, was anchored largely on environmental issues. The mining industry contributes to the gross domestic product of Ghana, but the illegal mining sacrifice environmental concerns in the interest of economic gains. In the midst of this, mining companies like Newmont with global acclaimed responsible and sustainable mining activities has obtained lease to mine in the Eastern corridor since 2013. As a global mining company with topnotch records of sustainability, Newmont have chalked success of an environmentally friendly mining company in Ghana. The aim of this study is to examine the corporate social responsibility and leadership style that underpin the company’s sustainable pro-environmental behaviors. This will aid in providing light for upcoming mining companies to tread on without compromising environmental concerns.

The overriding objective of this study is to discover the relationship between the corporate social responsibility of Newmont and its pro-environmental behaviors as company. These are the specific objectives:

1) To explore how Newmont captures environmental dimension in their corporate social responsibility.

2) To investigate how leadership style of Newmont promotes pro-environmental behaviors in the company.

3) To examine the pro-environmental behaviors adopted by Newmont Mining Company in Ghana.

4. Significance of Study

This study is relevant in contributing to the existing literature on corporate social responsibility and climate change by adding the relationship that exists between CSR and pro-environmental behaviors of companies, Newmont. The overall relevance of this study is to practically create awareness of pro-environmental behaviors that can help tackle the issues of climate change from the individual level. The study seeks to divert from the dominance CSR importance as philanthropic tool to CSR importance as anthropogenic tool in tackling environmental concerns of corporations in Ghana.

5. Delimitation of the Study

The study is delimited to Newmont Mining Company even though there are other mining companies that could have been included. These company is selected because of limited time for the study and the fact that it has a track record of environmental sustainability behavior over the years. Moreover, mining companies because they are one of the major sectors that pose high environmental concerns, hence the need to explore how they manage that through CSR activities and pro-environmental behaviors.

6. Review of Literature

The current study reviewed literature in three main themes, the conceptual framework, the empirical studies and the theoretical framework.

7. Conceptual Framework

This section discusses some key concepts such as climate change, Corporate Social Responsibility, pro-environmental behaviors that need to be operationalized in the current study for easy understanding.

7.1. The Meaning of Climate Change

Robertson and Barling (2013) considered climate change as a serious global issue that poses many risks to environmental and human systems. One of the greatest and urgent challenge facing human kind is the climate which comes with serious health, economic, environmental and social repercussions (Kazdin, 2009) . The two major causes of climate change are normally found to be natural variation or human activity with the anthropogenic factor being the largest contributor to climate change (National Research Council, 2010) . The trickle-down analysis of the anthropogenic causal factor of climate change shows that organization or companies are one major cause of climate change (Trudeau & Canada West Foundation, 2007) . This discovery has prompted some organizations to adopt formal and informal environmental management systems (Darnall, Henriques, & Sadorsky, 2008) . This adoption of formal systems is largely witnessed in the revision of corporate social responsibility policies to reflect the green demands of environmentalists. In Ghana, companies such Newmont are implementing policies to aid in their environmentally friendly behavior. This and many other policies are embedded in the companies’ policy documents, thereby affecting employees’ behavior towards the environment.

7.2. Understanding Pro-Environmental Behaviors

Russell and Griffiths (2008) in adopting Ramus and Steger’s (2000 cited in Russell & Griffiths, 2008) definition of workplace pro-environmental behaviors defined pro-environmental behaviors as “any action taken by employees that the employee thought would improve the environmental performance of the company” (p. 606). In other words, it is the behavior taken as result of employees’ shared knowledge of the action contribution to company’s environmental communication. This implies that policy documents such as CSR documents, if available and imbibed by workers could influence organizational culture towards pro-environmental behaviors that better the organization’s bit to achieve green compliant. This relationship between pro-environmental behavior and policy of organization demands a leadership style that favors such environmentally friendly narrative. Robertson and Barling (2013) define environmentally-specific transformational leadership as a manifestation of transformational leadership in which the content of the leadership behaviors is all focused on encouraging pro-environmental initiatives.

In this same lens, Daily, Bishop, and Govindarajulu (2009) are of the view that merely adopting systems is insufficient. This is because climate change is largely driven by human activity, and the success of environmental programs often depends on employees’ behaviors (Daily, Bishop, & Govindarajulu, 2009) . To them, fostering employees’ pro-environmental behavior within organizations is now critical. This requires a leadership style and policy initiatives that encourages workplace pro-environmental behaviors, such as recycling, conservation, and waste reduction behaviors as measures to contribute to the greening of organizations and positively affecting climate change and prevent further environmental degradation. As Robertson and Barling (2013) argued, the need for human behavioral modification toward more pro-environmental behaviors is well recognized by researchers, who point to the need for empirical research that investigates how promoting workplace pro-environmental behaviors can be achieved. Robertson and Barling (2013) call for organizational researchers to focus on fostering pro-environmental behaviors within organizations by developing and testing a model that suggests that organizational greening activity can be achieved through leaders’ influence on employees’ workplace pro-environmental behaviors. Such leadership will sway the corporate social responsibility narrative from being predominantly economic and philanthropic to capturing the environmental aspect of CSR.

7.3. Corporate Social Responsibility

Carroll (1999) offered one of the most accepted definitions of CSR, and the European Commission (2011) expanded his definition by conceptualizing corporate social responsibility as “a practice which corporations undertake to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders” (p. 681). This definition opens addition of the environmental responsibility of CSR answers Willard (2002) cited in May, Cheney, & Roper (2007) who questioned the absence of “environmental” in the CSR set as a drawback in the conceptualizing of CSR as largely social rather than environmental.

The call for environmental responsibility of corporation is louder today than ever because of the rising climate change situation in the world today. May, Cheney and Roper (2007) observed that CSR communication encapsulates a communicative practice, which corporations undertake to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders. From the corporate documents, one could have an idea as to how an organization could fare in the area of environmental front of CSR and its impact on pro-environmental behaviors of the organization.

8. Empirical Reviews

The interaction between leaders and employees on environmental issues could be governed by organizational policies. This is normally justified under the lens of corporate social responsibility position and communication of corporations. Nielsen and Thomsen (2018) conducted a systematic review of 151 articles within fifteen years period in the area of corporate social responsibility and corporate legitimacy and they found that the researches were largely approaching the CSR communication and corporate legitimacy from three major strands. The first strand was classified by Nielsen and Thomsen (2018) as perception, impact, and promotion studies of CSR relationship with corporate legitimacy. These studies considered CSR communication as highly monologic with emphasis on promotion of corporation to gain purchase ( Perez, Rodriguezdel, & Bosque, 2013; Pomering & Dolnicar, 2009; Sora, 2011, Stanalan, et al., 2011; etc).

The second strand were classified by Nielsen and Thomsen (2018) as performance studies which used dialogic communication techniques to engage in corporate marketing-oriented communication ( Fieseler & Fleck, 2013; Golob & Podnar, 2014; Nwagbara, 2013; etc). The last strand of studies on CSR and corporate legitimacy identified by Nielsen and Thomsen (2018) is the CSR communication conceptual and rhetorical studies which focused discovering effective persuasive techniques and models to win stakeholders approval ( Schultz, Castello, & Morsing, 2013; etc). With this broad scrutiny of CSR literature and corporate legitimacy, the area that was left gray in Nielsen and Thomsen (2018) examination of the content and themes of the research publication under their review was the lack of attention on the environmental responsibility of achieving corporate legitimacy. There is an overwhelming lack of focus on the environmental threats posed by corporations and the place of CSR in handling the concerns of stakeholders.

With regards to CSR and environmental issues, recent studies have focused on understanding the role of corporation in championing the green agenda. The literature is divided into two perspectives, thus those considering the environmental hazards posed by corporations to the environment such as oil spillage, waste management, CO2 emission among others ( Okereke, Wittneben, & Bowen, 2012; Tang, Gallagher & Bie, 2015; etc). This perspective is not missing in the Ghanaian literature where there are evidences of mining activities impact on the environment (Ansu-Mesnah, Marfo, Awuah, & Amoako, 2021) . On the hand, the most recent publications are toeing the line of corporations’ environmental management procedures as a component of their CSR activities and communication. Here, the focuses are the overall corporate initiatives as well as the individuals in the corporation chain behavior to environmental issues. Afsar, Cheema, and Javed (2018) discovered that perception of CSR has a positive effect on the individual pro-environmental behaviors in the organization. Shah, Cheema, Al-Ghazali, Ali and Rafiq (2021) equally discovered that the behaviors of individuals in the corporations in pro-environmental way are largely based on CSR position of the organization. Raza, Farrukh, Iqbal, Farhan and Wu (2021) explored CSR perception and pro-environmental behaviors of employees in the hospitality industry in Pakistan and found that CSR directly affect pro-environmental behavior. Unsworth, Davis, Russel and Bretter (2021) explored the macro factors, such as organizational leadership, capabilities and human resource management and micro factors such as employees’ values and self-concordance on pro-environmental behavior. Unsworth et al. (2021) concluded that macro factors do not work uniformly but the employees’ environmentalism is the defining factor.

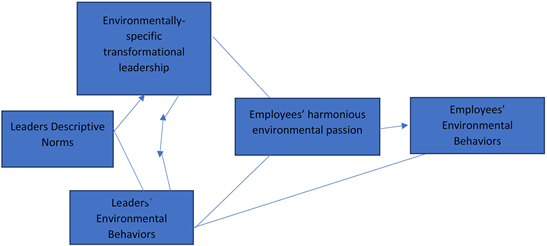

In their study, Robertson and Bailing (2013) explored workplace pro-environmental behaviors and the how leadership style could affect it. They discovered a connection that environmentally-specific transformational leadership and leaders’ workplace pro-environmental behaviors to employees’ pro-environmental passion and behaviors. Robertson and Bailing (2013) revealed that leaders’ environmental descriptive norms predicted their environmentally-specific transformational leadership and their workplace pro-environmental behaviors, both of which predicted employees’ harmonious environmental passion. In turn, employees’ own harmonious environmental passion and their leaders’ workplace pro-environmental behaviors predicted their workplace pro-environmental behaviors. These findings show that leaders’ environmental descriptive norms and the leadership and pro-environmental behaviors they enact play an important role in the greening of organizations. This confirms the idea of Barrow (1999) that not all people are concerned about environmental issues and so the leadership as suggested in the model by Robertson and Bailing (2013) could be a trigger to achieve the overall organizational pro-environmental behavior.

Leaders are found to have great influence on environmental performance (Ramus & Steger, 2000) . Robertson and Barling (2013) developed a model based on the argument that the greening of organizations can be enhanced through the influence of leaders’ environmental descriptive norms, their environmentally-specific transformational leadership, and their workplace pro-environmental behaviors. Their model is based on the assumption that leaders’ environmental descriptive norms predict their environmentally-specific transformational leadership and their workplace pro-environmental behaviors, which in turn predict employees’ harmonious environmental passion. Likewise, their model assumption is that employees’ harmonious environmental passion and leaders’ workplace pro-environmental behaviors predict employees’ pro-environmental behaviors.

9. Theoretical Framework

Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Theory

Robertson and Barling (2013) discussed the leadership style that could enhance pro-environmental behaviors in a company. They developed a model that explains that the leadership behaviors regarding the environment have a huge stake on the pro-environmental behaviors of the company. Transformational leadership includes four behaviors namely: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass, 1998; Bass, & Riggio, 2006) and the application of these behavioral leaders’ behaviors can influence environmental sustainability within organizations.

First, idealized influence centers on leaders becoming role models by doing what is right rather than what is expedient. Leaders influence employees through their moral commitment to their followers and the collective good. In manifesting idealized influence, leaders are guided by a moral commitment to an environmentally sustainable planet (the collective good) and choose to do what is right by encouraging actions that will benefit the natural environment. In doing so, environmentally-specific transformational leaders serve as role models for subordinates, who then become more likely to engage in these behaviors themselves.

Second, leaders high in inspirational motivation stimulate their employees to go beyond their individual needs for the collective good; they inspire subordinates through their own passion and optimism to overcome psychological setbacks and external obstacles, and to go beyond what is good for themselves by engaging in behaviors that benefit the natural environment. Third, intellectually stimulating leaders encourage employees to think for themselves, question long-held assumptions, and approach problems in innovative ways. Within the context of influencing environmental sustainability, leaders high in intellectual stimulation encourage subordinates to think about environmental issues for themselves, question long-held assumptions about their own and their organization’s environmental practices, and address environmental problems in an innovative manner. Finally, leaders who exhibit individualized consideration display compassion and empathy for employees’ well-being and help employees develop their potentials and skills. In doing so, leaders establish close relationships with followers within which they can transmit their environmental values, model their environmental behaviors, and raise questions about environmental assumptions and priorities. In short, through environmentally-specific transformational leadership, leaders use their relationship with subordinates to intentionally influence and encourage their subordinates to engage in workplace pro-environmental behaviors.

Robertson and Barling (2013) conceptualize environmentally-specific transformational leadership as a unidimensional construct comprising the four components for several reasons. First, they believed that consistently high correlations are yielded between the four components, thereby supporting the combination of all four components (Barling et al., 2010) . Second, recently developed measures of transformational leadership in organizations (Herold, Fedor, & Caldwell, 2008; Rubin, Munz, & Bommer, 2005) and classroom settings (e.g., Beauchamp et al., 2010 ) use unidimensional scales. Third, an exploratory factor analysis on safety-specific transformational leadership vindicated the use of a unidimensional index of the construct (Barling et al., 2002) . For these reasons, a unidimensional approach to environmentally-specific transformational leadership

First, the theory assumes that descriptive norms of leaders affect the followers pro-environmental behaviors. Descriptive norms refer to people’s perceptions of what most others do (Cialdini, 2007) , and these perceptions can motivate behavior by conveying important social information about effective and adaptable behavior (Cialdini, 2007) . When individuals follow the lead of others, they speed up the decision-making process such that time and cognitive effort are saved, while appropriate behavior likely results. In the environmental context, environmental descriptive norms provide information that pro-environmental behaviors are effective and adaptable in the given context, and they have been shown to have powerful effects on pro-environmental behavior. Robertson and Barling (2013) propose that environmental descriptive norms will influence leaders when they reference friends, family, and colleagues (similar others), such that leaders’ perceptions that similar others engage in pro-environmental behaviors will directly influence their own workplace pro-environmental behaviors. For the same reasons, leaders’ environmental descriptive norms will influence the behaviors they choose to emphasize and encourage among their subordinates when in leadership positions, and therefore, will affect their own environmentally-specific transformational leadership.

First, through the moral commitment to the environment that is characteristic of idealized influence, environmentally-specific transformational leaders will likely elicit employees’ harmonious passion for the environment. Similarly, enunciating a vision in which environmental sustainability is paramount signals what is most important in the workplace and to the leader. Employees are more likely to be passionate about something of organizational and social importance. Second, by encouraging employees to go beyond their own needs for the collective good, and inspiring them to achieve more than they thought they could, leaders who manifest inspirational motivation will engage employees’ harmonious environmental passion. Specifically, inspirational motivation will create optimism about one’s personal contribution to the organization’s environmental sustainability and thus ignite employees’ passion. Third, consistent with intellectual stimulation, encouraging employees to think about the environment in new and optimistic ways, and thinking about the effects one’s own behavior can have on the environment, will engage followers’ harmonious passion for this issue. Fourth, the interpersonal behaviors consistent with individualized consideration (e.g., caring, mentoring) create an interpersonal relationship in which employees are more amenable to leaders’ influence about environmental issues.

Organizational leaders are ideally placed to serve as role models because of their position, status, and power (Brown et al., 2005) . By displaying a consistent pattern of pro-environmental behaviors, leaders signal to employees that such behaviors are valued and expected in the workplace. In doing so, subordinates learn that enacting such a behavior will lead to desirable consequences and therefore will be motivated to engage in these same behaviors themselves. Unlike environmentally-specific transformational leadership, leaders engage in workplace pro-environmental behaviors to be consistent with their values rather than through any intention to influence others. In turn, when employees watch their leaders engage in workplace pro-environmental behaviors, they learn 1) that such behaviors are valued, expected, and rewarded; and 2) how they can engage in similar behaviors.

In addition, emotional contagion occurs among subordinates when they watch their leaders passionately engage in workplace pro-environmental behaviors. Robertson and Barling (2013) defined emotional contagion as the automatic and unconscious process by which individuals harmonize and imitate facial expressions, vocalizations, and movements of others, thereby resulting in the transfer of emotions between individuals. Research in both laboratory and field settings demonstrate that emotional contagion occurs between leaders and followers. Subordinates will synchronize and imitate the expressions, vocalizations, and movements their leaders emit when passionately engaging in pro-environmental behaviors. In turn, this will result in emotional contagion and, consequently, ignite employees’ harmonious passion for the environment. Robertson and Barling (2013) argued that predict that employees’ harmonious environmental passion will lead to workplace pro-environmental behaviors for several reasons. First, experiencing harmonious passion is energizing, leaves individuals inspired to make a difference and results in a motivation to engage in the activity that is the object of the passion (Vallerand et al., 2007) . In the context of harmonious environmental passion, this would include engaging in behaviors that should improve the environment. Second, positive emotions (e.g., happiness and joy) influence workplace pro-environmental behaviors and harmonious environmental passion is a positive emotion. Third, indirect support for the role of environmental harmonious passion as a mediator derives from a recent study showing that harmonious passion can indeed play a mediating role (Dong, Chen, & Yao, 2011) .

The model developed by Robertson and Barling (2013) is presented in the figure below.

10. Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Model

This model by Robertson and Barling (2013) depicts how environmentally specific transformational leadership as opined in their theory correlates with ecployees’ pro-environmental behaviors. From the model, environmentally specific transformational leadership posits that when leaders use descriptive norms as well as engage in the environmental behaviors themselves; employees are inspired to adopt those pro-environmental behaviors in the organization (Afsar & Umrani, 2019) . The models therefore, depicts that transformational leaders are able to trigger employees to adopt pro-environmental behaviors in an organization.

This theory aid in understanding the pro-environmental activities of Newmont and the extent to which such behaviors could affect the overall performance of the company on environmental issues. Secondly, the theory provides guides as to how different factors in the organization such as leadership and leadership style impact pro-environmental behaviors of companies.

11. Methods

The current study is using qualitative research method with the content analysis as the main design. The qualitative research method is very useful when data collected is not largely numerical in nature and may not requires the use of statistical tools to make sense of the data. In the current research, the researcher collected secondary data from the Newmont company websites for analysis. The reports were sustainability reports of the company for 2020 and 2019 because these were the years that the mining industry was greatly criticized for destructive activities against the environment. Also, efforts were made to reach the company leaders for a telephone based informal interview to compliment the data gathered from the online site. The data was processed based on the research objectives that underpinned the research. The researcher employed qualitative content analysis as a data analytical method. The content of each sustainability report was typed into Microsoft word for easy references. Also, the researcher ensured pictures and images were excluded from the selected data so that the researchers could use only the word-based data for analysis. The themes developed for the content analysis were guided by the theoretical framework as well as the empirical evidence discussed in the previous chapter.

Regarding ethics, the credibility of the secondary data was assured through the consideration of the copyright and publisher details of the data. Moreover, the online calls session with the leaders of the Newmont has aided in making it possible to confirm the secondary data. The intention of the research was made known to the company and their consent was sought before progression to the work. The anonymity and confidentiality of the sources were assured as part of ensuring ethical dimension of the research.

12. Results and Analysis

From the secondary data, thus the company’s sustainability report, it was discovered that Newmont has rich understanding of climate change and the role of the organization in achieving climate change global standards as well as employees’ compliance to pro-environmental behaviors. The Chief Executive Officer and shareholder of Newmont, Tom Palmer, asserted that they are committed climate change issues and they have a Climate Strategy Report aligns with recommendations by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and details Newmont’s governance and climate-related risks, scenarios and opportunities. As Palmer indicated:

The annual Climate Strategy Report, our proxy statements, annual reports, and sustainability reports such as this, are all important documents where we share our standards, metrics and the way we achieve those results.

In line with this, the first research objective was to explore how Newmont captures environmental dimension in their corporate social responsibility. From the analysis, it was discovered that Newmont has captured environmental concerns as part of its corporate values on sustainability and business strategy on environment. From the sustainability report, it was discovered that Newmont indicates on sustainability as a value:

We serve as a catalyst for local economic development through transparent and respectful stakeholder engagement and as responsible stewards of the environment.

This means that Newmont is values the environment and position themselves as stewards of the environment. In the business strategy, Newmont asserted that they are committed to:

Environment, social and governance Achieving long-term competitive advantage through leading sustainability practices to enable business continuity and growth, support positive social transformation and create shared, long-term value for all our stakeholders. Sound environmental and social management practices drive operational excellence, reduce costs and mitigate operational risks: all of which are foundational to Newmont’s broader purpose and business strategy.

This business strategy shows the position of Newmont as a company that handles environmental issues in a sound and responsible manner. This is done through their conformity to international health, safety and environmental standards. In an interview with the customer care of Newmont, it was indicated that in Ghana, Newmont regional leaders engaged with the Environmental Protection Agency to resolve permitting delays and challenges; the Ghana Revenue Authority to ensure the provisions of the Company’s. Likewise, the company is committed to Investment Agreements to Set GHG emissions and intensity reduction targets of more than 30% (Scope 1 and Scope 2) and 30% (Scope 3) by 2030 and net zero carbon by 2050. By all standards, the company policy standards from values to business strategy to climate change and sustainability communication have incorporated environmental concerns of the company.

The second research objective was to investigate how leadership style of Newmont promotes pro-environmental behaviors in the company.

On this objective, sustainability report of Newmont indicated that the Regional Senior Vice President is the leadership of the environmental concerns.

General Managers have responsibility for ensuring each site fully complies with external obligations including regulatory and permitting requirements and our internal environmental standards and procedures. A member of the Regional Senior Vice Presidents’ leadership team is responsible for environmental management activities at the site and across the region, and these individuals report to their functional leader at the corporate office developed and grown, and is now part of the fabric of the Company and central to all our actions.

In line with this, the leaders have taken actions by ensuring that 10,000 employees changed work locations from Newmont sites and offices to remote work environments. This behavior of ensuring the safety of employees by relocating them to safe environment communicates the environmental behavior of Newmont. In April 2020, Newmont created the COVID-19 Global Community Support Fund, a $20 million fund established to address three key areas of need: workforce and community health, food security, and local economic resilience. At the close of the year, we had contributed nearly $11 million, bolstering our existing local community contributions and efforts. The principle of Newmont is to ensure safety of their communities. This pandemic will continue to challenge all of us for some time and our commitment to protect the health and safety of our workforce and host communities will remain our underlying principle.

Robertson and Bailing (2013) predicted that the leaders’ pro-environmental descriptive norms could contribute to pro-environmental behaviors. Newmont discovered that reduce Green House Gas (GHG) emissions intensity (tonnes of carbon dioxide per gold equivalent ounce) 16.5% by 2020, based on the 2013 re-baseline. To achieve this, Newmont leaders have resorted to lower production in 2020, due to temporarily placing some sites in care and maintenance during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. They have reduced our GHG emissions intensity by 13.9%.

Aside that, Newmont has implemented specific initiatives towards achieving the environmental goals such as reduction in withdrawal intensity from surface and groundwater; refine processes to reduce water use and loss; increase reused and recycled water as a percentage of total water used in mineral processing, and achievement of 90% of planned reclamation activities/associated actions across the Company.

The third objective is to examine the pro-environmental behaviors adopted by Newmont Mining Company in Ghana. From the sustainable report used in this study, it was discovered that Newmont adopted five major pro-environmental behaviors to achieve environmental sustainability. These behaviors include reduction, reuse, recycling, reclamation and closure. As indicated in their document:

Regarding the reduction behaviors, Newmont has minimized the use and amount generated of hazardous materials, inclusive of hydrocarbons and cyanide, by replacing hazardous chemicals with less hazardous products whenever possible. One example told in the report is:

We often use citrus-based solvents in our maintenance facilities instead of chlorinated ones. Hydrocarbon wastes (e.g., used oil) are the largest portion of our hazardous waste stream, which also includes equipment maintenance activity waste, such as grease and solvents, and laboratory chemicals. Our sites minimize the volume requiring disposal by recycling almost all waste oils and greases, either through third-party vendors or on-site processes, such as using waste oil for fuel in combustion processes or explosives.

Moreover, Newmont is committed to an industry-leading climate target of more than 30 percent reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 and to achieving net zero carbon by 2050.

Secondly, Newmont engages in recycling behavior. They make every effort to recycle or reuse non-hazardous waste. Through Full Potential, their global continuous improvement program, they have identified opportunities such as increasing the tire life on haul trucks, optimizing the use of reagents and other consumables, and identifying materials (e.g., HDPE pipes and valves) that could be recycled rather than disposed of in a landfill. Moreover, Newmont is engaged in ensuring that:

Each operation is required to manage waste rock and ore stockpiles in a manner that promotes beneficial post-mining land use, mitigates the release of pollutants to the environment, and reduces closure and reclamation liabilities. Sites must also minimize the risk to surface and groundwater quality from acid rock drainage (ARD), which is generated when water comes into contact with certain minerals in the rock that are oxidized by exposure to air, precipitation and naturally occurring bacteria. In instances where prevention is not possible, we collect and treat ARD in a manner that protects human health and the environment.

Regarding closure and reclaiming behavior, Newmont indicated that the closure is a multifaceted process with complex risks. Successfully closing and reclaiming mines is crucial for gaining stakeholder trust and maintaining our social license to operate. They capture this in the sustainability report as:

Our approach to providing long-term environmental stability and a positive legacy is detailed in our Closure and Reclamation Management Standard, and our public target promotes progressive reclamation at our operations. None of the cyanide spill events resulted in the solution leaving the property and there was no threat to communities or wildlife. Where required, the events were reported to regulatory authorities and the spills were cleaned up and remediated.

In an interview with Tom Palmer (Captured in the Sustainability Report), Newmont President and CEO, shares his thoughts on the impact of the pandemic and meeting the longer-term challenge of climate change. Tom Palmer has this to say concerning employees’ and leaders relationship regarding environmental issues:

Our employees are demanding leadership from Newmont. They want to see that we’re setting challenging targets, and they’re going to expect that we meet those targets or exceed them. They’ll also be looking for opportunities to help along the way. So, we’re going to see increasing momentum from within to change, expect change, support change and reward change in the climate space. And our success will ultimately be measured by whether we can continue to attract and retain the very best and brightest in the places we operate around the globe.

Regarding other mining companies, Newmont president and CEO admonished that there is the need to think beyond the traditional premise where mining provides that livelihood through jobs. There will still be some of those traditional jobs, but it’s going to be a much more automated operation. Tom Palmer asserted that:

We’ll need to lift the level of skill required, which creates an opportunity to increase the skill level in the communities. We also need to remember that a key part of our purpose is to create value and improve lives. It’s going to challenge us to think about how we create an economic livelihood that may be secondary to the mining operation and ultimately lives beyond the mining operation.

The pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, reuse, reduction, reclamation and closure are embraced by employees of Newmont thereby causing the organization to fare well in terms of environmental issues in Ghana.

13. Conclusion

The president of Newmont indicated that climate change is not a new issue for Newmont; it has become a material risk for the world, our industry and our organization. It is vital to ensure that the mining companies are not oblivion of their responsibility rather like Newmont, environmental responsibility like every other economic, social and philanthropic responsibilities should be anchored in the policy of a company, endorsed and implemented by leaders in their behaviors and widespread company pro-environmental behaviors for adoption. In the current study, the following major findings were discovered:

First, Newmont has included environmental responsibility in their company values and business strategy as a way to ensure sustainable environmental behaviors.

Second, Newmont leadership is spearheading the responsibility of implementing pro-environmental behaviors by complying with international regulation and implementing those regulations in the local mining sites.

Third, Newmont has adopted pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, reuse, reclamation, closures and reduction as measures to achieve environmental sustainability as a company. They have equally supported environmental sustainability campaigns through donations and sponsorships.

Recommendations

On this basis, I recommend other mining companies should consider revising their policy documents to include environmental concerns as the major step to shaping organizational culture and promoting the pro-environmental behaviors among employees.

Moreover, mining companies should adopt transformational environmental specific leadership styles as the major step to achieving the role of leadership in enhancing employees’ pro-environmental behavior. The leaders’ idealized behavior, pro-environmental descriptive norms as well as the use of harmonious passions positively influence the extent to which employees comply with environmental behaviors.

Furthermore, mining companies should consider adopting environmental behaviors such as recycling, reuse, reclamation and closures as major ways to achieve environmental sustainability. The companies should consider working at complying with international standards and implementing them in local settings. Finally, government should consider promulgating climate change policies for regulating the operations of mining industries in Ghana. In short, climate change is real and mining industries pro-environmental behaviors are relevant in regulating its intensity.

Acknowledgements

My appreciation to Newmont Mining Company for the opportunity to conduct this study on their mining company.