1. Introduction

The three authors of this article, a social worker, a systems engineer, and a social biologist, are professional futurists interested in human social development. The three authors also share strategic and foresight studies and a deep curiosity for understanding of human consciousness and the pursuit of meaning in life. Three different thinkers, brought together by Poetry.

This paper begins with the theme of Poetry, with the following quote by Nasir Abbas Nayyar:

“A few words first, about the nature of poetry. Poetry says little, intends more. It loves to remain ambiguous and nonchalant about its intended meaning. It leads gaps to be filled, by the perception of its readers.”

The very words depicted in this quote suggest that the reader has a role to play in the interpretation of a poem, and that the reader derives meaning through their own perception. An aesthetic approach to a scientific problem, and one which takes on a systems approach to uncover meaning which sometimes goes unnoticed and certainly rarely measured. In the case of this paper, we use poetry as a mnemonic to consider social work and derive a richer picture of the field.

Narratives of Social Work

Consideration of the nature and contribution of professional social work has been a consistent concern for more than a century since Abraham Flexner (1915) asked “Is social work a profession?”. Finding an answer is more like the interpretation of poetry than the combination of science and technology narratives demanded by Flexner.

This article seeks to reclaim the meaning of social work—the noun—from social work—the adjectival professional practice defining social work as “the work that makes societies work” (Benjamin, 1997a). Social work is defined by the International Federation of Social Workers (“FSW”) as:

“A game changer. Social worker work in communities with people, finding positive ways forward in the challenges they face in their lives. They help people build the kind of environment in which they want to live, through co-determination, co-production, and social responsibility”.

The Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) defines Social Work as:

“Social workers act collectively and individually to contribute to society in a way that is dedicated to achieving social justice, inclusion and social wellbeing”.

It sets out its vision as “Wellbeing and social justice for all”. Its purpose is “Supporting social workers and empowering the profession to make positive differences”.

These definitions are like poetry in their nature, and meaning are off the mind of the reader.

Flexner’s (1915) assertion that the profession was immaturely claiming status equivalent to doctors and lawyers drove a century of movement towards a hunt for recognition, registration, and respectability.

Payne (1996) identifies the purpose of social work as therapeutic in nature as the social worker tries to improve and solve the problems that individual people or families have in their lives.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary widens the field further as “any of various professional activities or methods concretely concerned with providing social services and especially with the investigation, treatment, and material and of the economically, physically, mentally or social disadvantaged”.

Flexner (1915) identifies the more general term—“social work” as “any form of persistent and deliberate effort to improve living or working conditions in the community, or to relieve, diminish or prevent diseases, whether due to weakness of character or to pressure of external circumstances”.

As Greenwood (1957) this approach to professional social work refers equally to social scientists, clergymen, pharmacists, physicians, surgeons, teachers, optometrists, judges, engineers, journalists and social workers.

In this article we leave the continuum of elite educated professionals, with years of tertiary education who are registered practitioners to unskilled, well-meaning citizens doing good for altruistic reasons.

Our interest lies in the construction and dissemination of an instrument that could be adjusted by any social worker seeking to understand and apply a social work framework to conceptions of social inclusion, social justice, social welfare, social organisation and/or social development.

The social construction of the practice of social work as the domain of organised effort to develop, maintain, and sustain societies and their capacity for the generation of personal agency and the production of supportive agencies requires further consideration.

Tackling this optimistic and adversarial objective requires an interpretation of practice, ontology, epistemology, teleology, relationships and yearnings for theoretical, technical, and therapeutic integration.

For the purposes of clarity, we define “social work” as an object of study: social work as the field of human service as the process of service to other community members and social work as the professional form, function, frame and focus of works accepting professional standards affecting educated credential status.

In this context, we will consider the field under the mnemonic POETRY:

• Professional practice.

• Ontology and outcomes.

• Epistemology and ecology.

• Teleology and techniques.

• Relationships and responsibilities, leading to.

• You/Your place and potential contributions.

A century after Flexner (1915), it is time to integrate information, matter-energy and social construction of reality to construct a consciousness and capacity to cope with coping and consciousness.

2. Professional Practice

Greenwood (1957) says that “the chief difference between professional and non-professional occupation lies in the element of superior skill, supported by a fund of knowledge that has been organised into an internally consistent system, called a body of knowledge.”

Every profession represents an organised series of interactions, information and intelligence that seeks recognition and registration of a knowledge base, skills transfer capacity and action potential directed towards both ecological associations to supranatural processes and performance consolidation. The practice of social work requires knowledge of human development. Social organisation and the interaction of individuals in societies.

The USA NASW defines social practice as: “the professional application of social work values, principles and technologies to one or more of the following ends”:

1) Helping people obtain tangible services;

2) Counselling and psychotherapy with individuals, families and groups;

3) Helping communities or groups provide or improve social and health services; and participating processes.

Flexner (1915) introduces six criteria for professional practice:

1) Intellectual operations with large individual responsibility;

2) Knowledge and procedures drawn from science and learning;

3) Application to practical and definite ends;

4) Possession of actionable communicable techniques;

5) Self-organisation and systems approaches; and

6) A commitment to the agency of people seeking to make life matter through systematic relations and responses.

He concluded that in 1915, social work was unable to comprehensively meet these criterion.

Anne Matheson et al. (2021) refer to the importance of mattering for any form of humanistic management research, theory and practice that provides important, human-centred, relationally oriented concepts to help us understand how people live and experience their lives.

Rosenberg & McCullough (1981) conceptualise what matters in work is the felt sense of whether the interaction between people gives them a measure of inter-dependence that reinforces an action-oriented appreciation of interest in each other’s well-being and feeling that they matter.

Applying this concept to the practice of social work involves a structured, functional orientation to the increased range of changes and choices that emerge from the interactions of at least two people engaged in increasing their sense of recognition and achievement of their goals in life, ability to reach for them and enhance social development.

What matters here is the dynamic interchange of interpersonal conditions to the construction of both personal agency-sense of being significant, and agencies relationships, forms, functions, frames and focus on the shred ecological environment that generates consciousness, collaboration, and community.

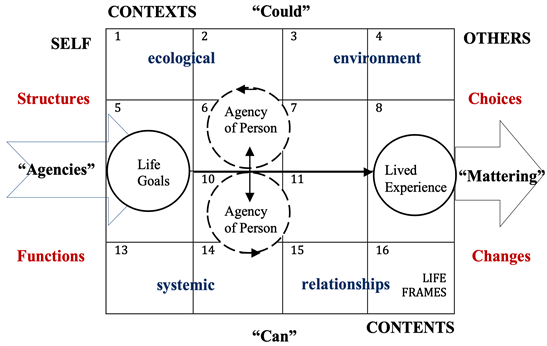

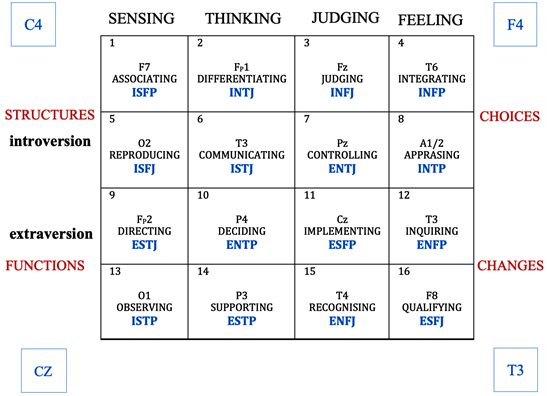

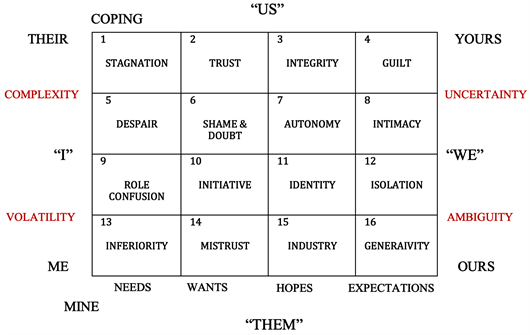

In Diagram 1, social work practice is seen as the mutual contributions of two people maintaining their own increasing sense of agency building on their contact with acceptable agencies supplying structures and functions that reinforce both personal and social agency that COULD and CAN enhance their action-oriented senses, thinking, judging and perceiving their mattering to both self and others.

Diagram 1. Social work practice.

Social work is collaborative, co-operative and consensual work relying upon information integration as the effort to manage coping and consciousness requiring a capacity of parties to make an investment of energy, space-time and meaning to maximise action potential for mattering.

Social work practice is a series of sub-system interactions of sentient and sensate people construing changes and choices that increase their individual and collective agency.

Every person functions within a potentially solipsistic, self-organising, staged a systems relationship between content and context as own object of knowledge, skills and application of control over elements of their ecological environments.

The practice of social work arises “if” and “only if” there is a sensation of the existence of “self” and “others” that establishes a requirement for coping and consciousness of the action potential of changes and choices to further lived experience, expertise, engagement, and enjoyment of life.

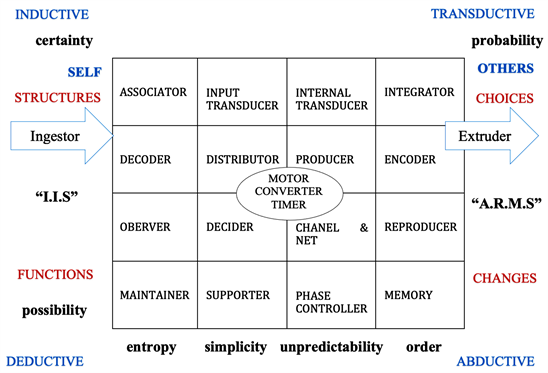

In order to construct a framework for the consideration of the content and context of social work practice, it is useful to consider the human brain as a living system and apply the observations of Carl Jung and the frameworks of neuroscience to patterns of interaction between internal and external influences. Miller’s (1978) multi-layered representation of Living Systems provides an initial representation of social systems.

Eight of these sub-systems process matter-energy and other ten only process information.

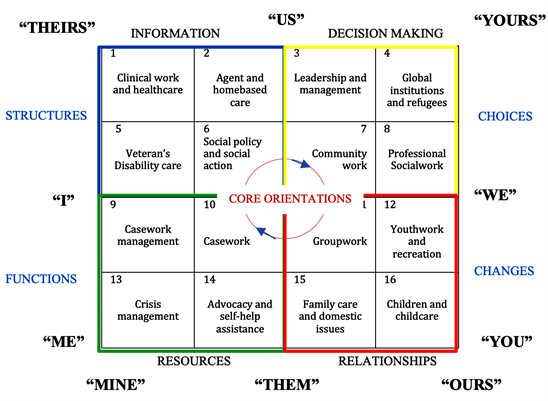

In Diagram 2, the twenty (20) sub-systems are presented as a matrix of process flows that establish, maintain, and sustain the social system that represents the components of social interactions between two or more human decision makers.

In the first column of this matrix, the transactions from people making changes

Diagram 2. James grier miller living systems theory.

and choices are senses, taken into consideration and associated within the action potentials if their contacts, contents and contexts.

In the second column this material and information is examined, considered and subjected to thinking processes of induction, deduction, abduction and transductive reasoning to provide comparisons, constructs, and creative expressions that determine values and priorities.

In the third column the alternative changes, choices and co-operation elements are sorted, selected and sequenced to produce combinations that are stored, produced and directed forward or placed in short-term memories.

In the fourth, and outwards facing column the integrated information becomes a source of pre-conscious, unconscious and conscious ideas, interventions and interactions that maintain, sustain and reproduce the living systems as a social motor, timer and parallel processing Advanced Relational Meaning System (“A.R.M.S.”) constructed within the twenty sub-systems of the Integrated Information System (“IIT”).

Processes that take place in these sub-systems include an internal transducer, information converter, chanel and net, decoder, timer, motor and phase controller that prefers, prioritises and promotes Nash equilibrium extensions from the inputs, throughput and output movements across the four columns to extend the life of decision makers.

The output of both decision makers is exchanged, combined or excluded from further immediate processing after being encoded, reproduced, extruded into the consciousness fields of their life support mechanisms through the output transducer and across boundaries within, across and between decision makers.

Each of the decision makers is able to process matter-energy and information required to construct a form of social reality, expression of sensations, thinking, judging and feeling/perceiving to expand their lifetimes and their social development.

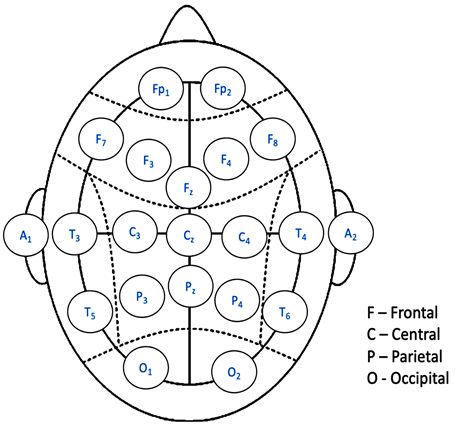

The elements of the human cortex that appears to provide the motor, timer, phase control and familiarity filter in this social system can be identified and measured with an EEG to offer an approximation of the practice of the decision takers in the process of inquiring, communicating, deciding an implementing alternative and alternating changes and choices (see Diagram 3).

This physical manifestation of the human brain as a living system provides an indication of the way that individual sensing, thinking, judging, feeling, perceiving and intuiting observed by Jung (1921).

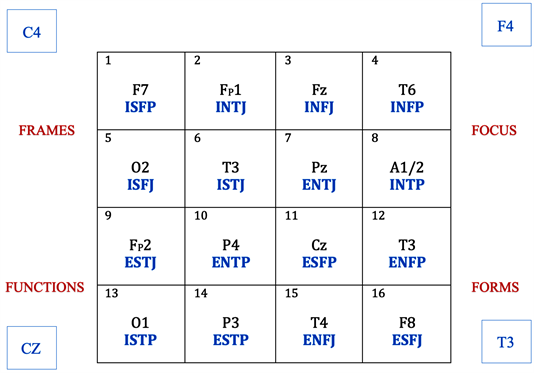

Jung’s personality types have been widely incorporated into social analyses as types, traits, temperaments and decision formats. There are eight functions:

Jung proposed the existence of two dichotomous pirs of cognitive functions:

• The “rational” (judging) with thinking and feeling

• The “irrational” (perceiving) with sensation and intuition, that are expressed in either introverted or extraverted form. These can be matched to brain functions (see Diagram 4).

Diagram 3. 16 EEG cortex contacts, bird’s eye view of the neo-cortex (Nardi, 2016).

Diagram 4. Brain region systems, jung types and Neocortex.

Combining Jung’s observed patterns with those of Nardi, it is possible o propose a relationship between the functions of the human brain that contribute to coping and consciousness and the way that the integrated information systems constructs social work processes.

According to Jung, rationality consists of figurative thoughts, feelings and actions with reason—a point of view based on a set of criteria and standards.

Non-rationality is not based on reason, not because they are illogical but because as thoughts they are not judgements.

Most of the sub-systems in the top two rows are seen to be associated with introverted responses to interactions with others and those in the bottom two rows associated with extraverted responses.

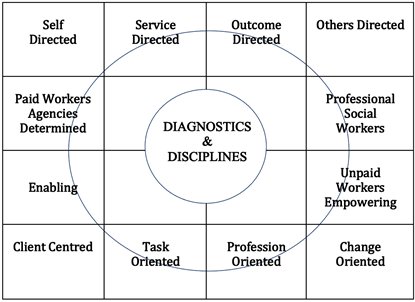

Analytical psychologist, John Beebe has matched the types to gerunds—activities associated with sixteen different “-ing” social interactions that people apply to become aware of other people’s changes ad choices inn life, then they are struggling with challenges (see Diagram 5). Again, these can be aligned with the components of Miller’s (1978) Living Systems framework.

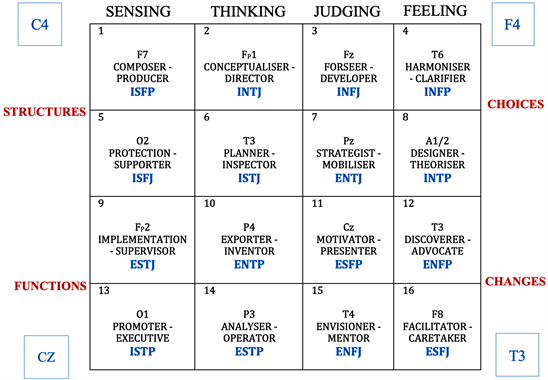

A wide range of labels and occupational types have been presented in the past fifty years as types, traits and temperaments that offer a measure of social, representation to increase appreciation of differences in the observed behaviours in social systems (see Diagram 6).

Note: Keirsey (1998) and Cattell (1943) have provided different layouts and labels, but these are presented here aligned to brain functions and patterns.

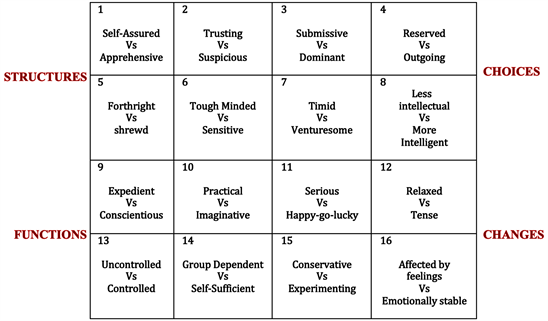

Unlike the type and temperament developers, Raymond Cattell built his trait theory from a large array of characteristics applying a mathematical computation developed by Charles Spearman. With the use of factor analysis, Cattell reviewed and categorised a large range of traits, seeking the most basic and useful

Diagram 5. John beebe psychological types, observed patterns of decision making.

Diagram 6. Occupational profiles.

ones and then devised a classifying scheme based in 171 different traits. This was reduced sixteen (16) basic source traits applicable to all humans (see Diagram 7).

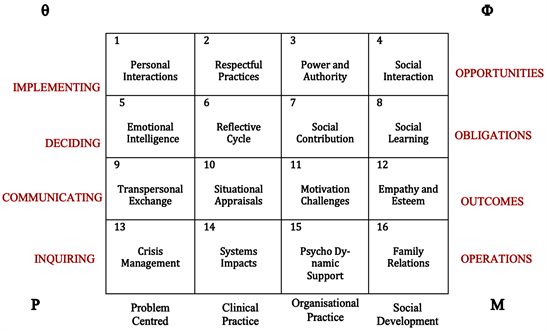

Cattell discovered that some traits are surface traits and others are source traits, the underlying structure responsible for the surface traits. Combining these theoretical and observed patterns of social interaction and the emerging underlying profile of approaches to change and choice provides a framework for comparison of social work practices (see Diagram 8).

Diagram 7. Cattell’s bi-polar traits.

Diagram 8. Eight social work system profiles.

This framework sets out the basis of P—Practice and Coping, M—Mechanics and Methods, θ—Theories and Techniques, and Φ—Philosophies and Consciousness.

This matrix represents a series of steps ranging from coping to consciousness that establish operations, outcomes, obligations and opportunities based on information integration processes of inquiring, communicating, deciding and implementing changes and choices.

Whereas personality types tend to encourage type casting and an indication that sixteen profiles are categorical, distinct and stable over long periods, there is little substantiation for this assumption.

Erikson (1950) also follows the perception that life stages are hierarchical, time related and dichotomous options that are relatively beyond the realms of conscious control or choice. However, an examination of observed differences between people’s life frames supports the contention that there are higher and lower frequencies of occurrence that have a socio-demographic origin (see Diagram 9).

Allocating the sixteen elements of Erikson’s eight life stages as responses to environmental VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) suggests that the pairs of developmental stages (8 × 2) provides an explanation of the drives of change and choice that underpin Erikson’s pairs of resolvable conflicts.

In this framework, all of these life frames are present in human decision making and become more or less significant over the lifetime of people.

Erikson’s approach presents these pairs of conflicts that generate personality development.

In the matrix version, these are all feasible approaches depending on the content and context of the environmental, genetic, epigenetic and nature of social interactions. In this framework the social development first serves the pressure of change that is a function of the volatility and turbulence of the environment and associations between people solving problems at varying life stages.

In the first column it is assumed that meeting the need for resources of energy and space-time are the highest priority to maintain and sustain life of the system—reliant on sensing needs.

Diagram 9. Erikson’s life stages.

In the second column it is assumed that balancing trust and distrust requires a balance between instinctive and the risks associated with shame and doubt—reliant on thinking about wants.

In the third column the emphasis is on judgements of viability and sustainability and establishing necessary and sufficient information to identify less likely and immediate actions that have the potential to add hope of a better life.

In the fourth and output-oriented column the focus is upon extension of the viability and the sustainability of the interconnections between different levels of organisation and between alternative living systems.

At all times there is a flow of energy and selection if the best available option with the least level of challenge to the overall pathway to change and choice. Every life frame is involved in the integration of information that constitutes the foundation of the entire open systems.

The matrix lays out a pattern of lower to higher levels of consciousness. At the bottom layer, the pattern establishes the grounded reality that strives to shift from inferiority and mistrust to a level of industry and generativity.

At the next layer, the increasing level of contact between people introduces a number of steps that clarify priorities and improve productivity. The next layer addresses emotional and reflective interactions to establish a sense of affiliative responsiveness and construct strong personal bonds between responding parties.

The top row conveys the strengths and powers necessary to achieve longer term goals and objectives and construct social infrastructure that delivers outstanding performance. Collectively the sixteen (16) LIFEFRAMES represent the interconnected social dynamic network that mobilises measured interactions and levels of consciousness on a step-by-step basis from passive to active layers of social development.

3. Epistemology

Hethersall (2016) suggests that discussions on theory and practice in social work have often avoided consideration on the nature of knowledge itself and the various ways this can be corrected.

In this article, therefore it is necessary to examine the manner in which practice wisdom emerges from the theoretical models that establish the validity and reliability of the LIFEFRAMES that are identified as elements of social work as a living system.

This is not the setting for a philosophical analysis of the foundations of differences between social work as the conjunction of “sociology” and “productive effort” or similar issues.

It is necessary to establish the criterion upon which the relationships between sub-systems of social work as a form of knowledge about the task associated with social justice, social inclusion and social development inform approaches to professional social work as a source of informed intelligence.

Mendes (2005) requests greater attention on research that documents specific links between social workers and social action and the knowledge base of social action-oriented workers contributing to their effectiveness.

Benn (1991) presents a case for consideration of the move away from early care work foundations of social work practice addressing individual defects in the development of new skills, emphasising the role of social workers in the development of new skills for social change.

In this section, accordingly, we seek to provide evidence of the development of a novel instrument that measures the practical impact of theoretical foundations enables greater emphasis on the defined goals of social work in social inclusion, social justice, social policy and social development.

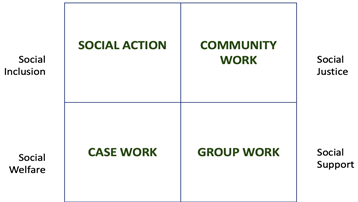

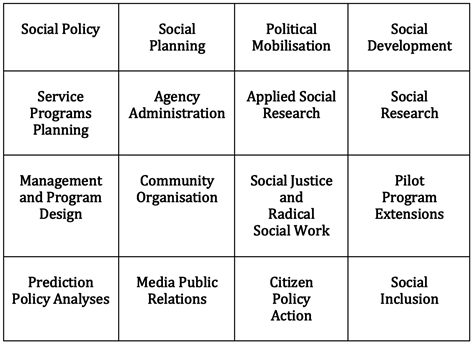

In Diagram 10(a), the more traditional perspectives of social work fields are presented in the practice of wisdom derived from social case work (e.g., Mary Richmond (1922), groupwork (e.g., Benjamin, 1997b), social justice of Nobel Prize winner Addams (1907) and Hamilton-Smith (2013), social environmental policy.

(a)

(b)

Diagram 10. (a) Forms of social work; (b) The practices of social work.

In Diagram 10(b), this wider frame of reference of fields of social work are presented as extensions over the past half century of new knowledge, skills and approaches in terms of the domain as an example of a living system.

It is suggested that social work as a profession has become more conscious of its contribution to the fields of identified by Benn (1991) and Mendes (2005).

Over the last fifty years, social workers have contributed to a substantially wider set of domains and practices.

Most professional social workers are employed in government services, private practice and more recently, in mental health and disability services industries although the predominant knowledge base is still heavily dependent upon “borrowed medical, psychiatric and psychological theories” from the central four LIFEFRAMES.

Case work (2014) is a phenomenon that aims to reduce experienced turbulence in people—in environment, problem solving, situational analysis and social justice operations that experience Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity (V.U.C.A.).

It is a process adopted by many clinical agencies, welfare service agencies, corrections and disability services, and mental health practice.

The principle knowledge base draws upon educational, psychological, sociological and economic development theories of Richmond (1922) and Jung (1921).

Groupwork (2020) is a way to work with people sharing common life experiences in settings that include child and family welfare, youth and recreation programs, corrections and local social control, education, refugees and socially isolated communities. This involves work with gangs, groups of self-help support, collectives, intimate groups, youth work, recreational programs and group therapy working with small and large groups comprising all age groups.

This field draws heavily on theories of Lewin (1935), Rogers (1961), Klein (1932), Homans (1960) and Konopka (1963).

4. Community Work (2013)

Fellin (2001) suggests that people who share an association with a locality and/or special local environments, usually grounded in neighbourhoods, villages and regional settlements often rely upon a community worker to coordinate interactions between sub-sets of that population.

The focus is on community organisations and human relations. Community provides avenues for identifications with shared language, partnerships, mobilisations of disaster responses and an effort to support community life. This field of practice in sociology, anthropology, human settlements and social psychology identifying avenues or greater social inclusion, social justice, community organisation and encouragement of self-help and self-determination.

This field draws its knowledge and practice wisdom from the writings of Saul Alinsky (1946), Freire (1970), Tew (2006), Wheatley (2012), Durkheim (1895), Etzioni (1968) and Upanmesk (2013).

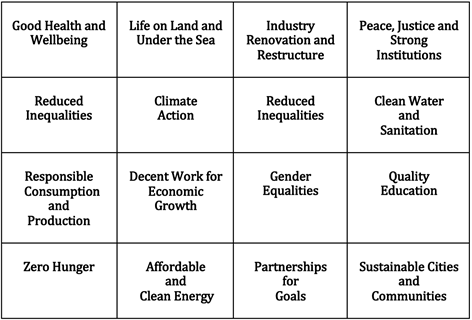

Community work includes community associations, community organisation, community service provision and community self-determination to address a wide range of goals and objectives (see Diagram 11).

Community social workers engage in distributive bargaining, local advocacy, service design and delivery and active lobbying.

5. Social Action

The most recent and broadest field of social work is social action. This is not the exclusive domain of professional social work as it covers all actions to promote social inclusion, social justice and social welfare.

The AASW indicates that the word “social action” refers to a range of voluntary actions aimed at addressing significant social, political, economic, ecological and ethical challenges (see Diagram 12(a)).

Charity humanitarian work, service delivery, public policy efforts advocacy campaigns, social movements, socio-political mobilisation and networking for desired social change have all been lumped together under the umbrella word— social action (AASW website).

Well, Reisch, & Ohmer (2013) refer to “practice that encompasses a dynamic set of theories, goals, ideologies, values, strategies, and tactics that seek to achieve a more egalitarian, open and socially just world through the creation of fundamental structural, institutional, ideological, attitudinal, and behavioural changes in communities, societies and individuals” (West, 2022).

Key theories of the social action model include empowerment theory ecosystem, social support and social network perspectives. Topics addressed include community assessment, action planning and radical community organising (West, 2022).

Unlike other social work methods, social action emphasises on long-term essential changes in established social institutions. Social action covers movements

Diagram 11. Focus of Australian Association of Care Workers (ACCA, 2019).

(a)

(b)

Diagram 12. (a) Social action focus; (b) Processes of social development.

of social, religious and political reforms, social legislation, racial and social justice, human rights, freedom and civic liberties (The New Social Worker, 2021) (see Diagram 12(a) and Diagram 12(b)).

Social action is a process used in program and wide range of protest movements. It is a general form of social work which contribute to social development processes:

6. Teleology

All forms of social work practice can be considered to contribute to improved levels of wellness, and most are committed to improving people’s agency, self-direction and freedom of choice.

Casework, Groupwork and Community Work share this orientation of starting where the client is, separation of the worker and the client and aiming to respect individuation within a physical and social environment.

The professional social worker who accepts a peer accountability, represents agencies and social institutions and priority of religious orientations tend to place a higher criterion of “doing the right things” over human rights, person-in-environment or situational assessment. They are committed to “Being Good” over “Doing Good”.

This introduces the teleological perspective to the functions and structure with an emphasis on “outcomes” and future consequences if current changes and choices. It accepts that “what is to be done” is more important that “who does it”.

Cowan (1968) indicates that socially oriented workers have different understanding if purpose, intentions and ethical behaviour based upon subjective experience from objective, scientific and empirically oriented workers who focus on cause and effect, evidence-based practice and concern about prior cause over future potential. It is important to clarify distinctions between actions taken and purpose—intentional acts—and action taken to achieve an outcome—to achieve a purpose or strategic intent.

Professional social workers are committed to the pursuit and maintenance of human well-being, to maximising human potential and the fulfilment of human needs through an equal commitment to:

1) Working with and enabling the best possible levels of personal and social wellbeing.

2) Working to achieve social justice through social development and social change.

This teleological orientation provides a boundary condition between the set of all social workers and the subset of professional social workers aligned with their association.

There is further division between those people who are paid, employed or self-employed that are receiving direct benefit for the service to and for others and unpaid volunteers or religiously aligned social workers who are unpaid, regardless in both cases of their fields of practice or roles engaged the practice of social work (see Diagram 13).

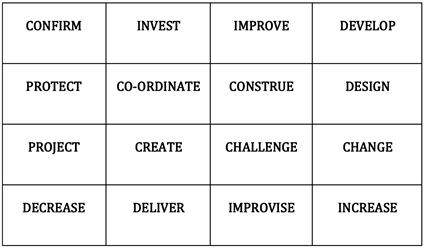

Diagram 13. Orientations.

A further boundary exists between workers, paid or unpaid, professional or not, who are client or customer oriented determined by their agency and workers who are goal-oriented agents of change (see Diagram 14).

The teleological perspective enables delineation of social work that is bound by an orientation to empowerment of other people and social work which tends to be social welfare neither than societal wellbeing directed.

In Diagram 14, there are ten boundaries between workers:

1) Welfare and Wellbeing

2) Client centred vs other centred

3) Paid and unpaid workers

4) Registered and unregistered workers

5) Social workers and social workers

6) Qualified and unqualified workers

7) Professional and unprofessional workers

8) Case services and service activities

9) Known information and unknown information

10) Problem solving and person-in-environment versus situational assessment and social capital.

This means that the nature of social work practice is a functional and structural arrangements determined by their form, functions, frames, and focus and “self” and “others”.

How these boundaries are maintained or crossed therefore depends upon the interests, intentions and information available on what is known only to the worker, known to workers and others and unknown to both people-in-environment or situation.

Diagram 14. The nature of social work.

The manner to which the worker reflects, relates and rejects needs, wants, hopes and expectations is significantly shaped by consciousness, awareness and the level of certainty required for their practice.

The teleological orientation upholds the agency of all who are seeking changes and choices within the bounds of framework of problem solving, person-in-environment, situational assessments and formation of social capital for future generations.

Whereas traditional case work, group work, community work and social action driven by ontology and functional heritage, a focus on social capital and human agency is presented as an open-systems, future oriented and collaborative commitment to human wellbeing.

The focus upon purposes, outcomes and teleology moves the knowledge, information and competence intentions away from the past conditions to awareness of criterion for change and choice.

Adopting a broader scale and scope for social work as a responsible rather than responsive orientation introduces considerations such as Nagel (1961) Structures of Sciences, Berlin’s (1953) hedgehogs and foxes constraints in focus and Dembski (1968) information and probability, Popper (1945) writings on falsifiability and confirmation of our assumptions about assured outcomes and Snow’s (1959) Two Cultures and Dembski’s (1968) Chaotic conditions.

7. Relationships

Professional social work’s challenge from Flexner (1915) remains intact a century later.

It is not sufficient to apply history or scientific findings about the nature of social work to establish the way that its practice actually gets desired outcomes without clarifying the relationships between functional sub-systems and the entire domain of the field of decisions about directions.

Social work operates at the boundary or interface of meaningful interactions of two or more people seeking to address avenues to greater enjoyment of life, performance of intentions and the relationships between solutions to the social contexts, contents and conflicts in approaches to social development.

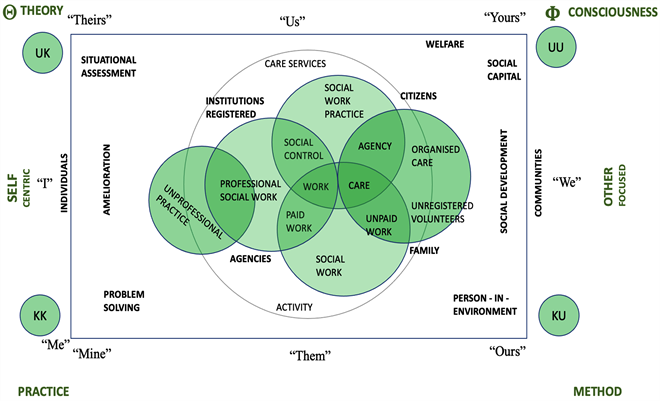

Other disciplines have a claim to professional acceptance based upon the brain, neuroscience, psychology, personality patterns, power and practice wisdom derived from operational constraints. Social work bridges the relationship between individuals and institutions seeking to improve on prior patterns of experience, expertise, and engagement with social reality (see Diagram 15).

Social work seeks to achieve better lifestyles and lived experiences by a process of persuasion and integration of information that enhances social capital, consciousness of probable outcomes and expanded action potential.

This involves the worker’s social reality providing additional and alternative goals and objectives based on the relationships between workers and significant others development of social relationships that expand their individual degrees

![]()

Diagram 15. Social work boundaries.

of freedom—the Nash Equilibrium acceptable outcome that is mutually beneficial.

Holland (1980) and Sherif (1963) provide a social judgement theory that explores the way that people manage differences in needs, wants, hopes, expectations through communications, messages and exchanges of value that lead to changes and choices on later behaviour.

Social work establishes positive relationships that enable social judgements that facilitates the emergence of social development and agency.

Caldini (2007), W.P Carey, distinguished Professor of Marketing at Arizona State University has identified a set of characteristics of persuasion that can be linked to the sixteen LIFEFRAMES that engage people in decisions relating to change and choices (see Diagram 16).

Caldini sets out six fundamental principles that lead people to work together to make changes and choices to an outcome of their communications and relationship:

1) Reciprocation

2) Commitment and consistency

3) Social proof

4) Liking people

5) Authority

6) Scarcity

This frame incorporates the Big 5 OCEAN traits that may be applied later.

8. You and Your Contributions

Any social development emerges from interactions between people who agree to work together to increase their chances of being more active and living more of their lives.

![]()

Diagram 16. Influences on effective relationships.

Living systems that are maintained and sustained by collaborating, constructive and cooperating people are self-organising, empowering and engaged individuals exchanging their lived experiences and learned expertise to engage in processes that increase enjoyment of life.

In the absence of access to the future because of unknown unknowns contingencies, social development emerges to enable collaboration, resolve conflicts and contribute to environmental behaviours that integrate various functions and multi-level structures that expand their joint and independent chances, changes and choices of reproduction and generation of life forms and futures.

Ultimately it is this set of LIFEFRAMES enabling social organisation that enable people to work together to generate environments that foster the potential for intergenerational societies to form and function.

The Advanced Relational Meaning System of human organisation (“A.R.M.S”) requires consciousness and coping with the action potential ad development of a hierarchy and holarchy of social relations from local and global scales.

Hofstede (1984) in Culture’s Convergences identifies a cross-cultural set of dimensions that enable people to communicate, cooperate and construct societies that work.

The six dimensions are:

![]()

The elements of social reflection of SELF and OTHER provide the minimum set of boundary relationships sufficient to contribute coping and consciousness capacities (see Diagram 17).

![]()

Diagram 17. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.

Ultimately, social work may be seen as an international way that people can make society work to maintain, sustain, and develop living communities an societies that construct the relationships of You and Yours that facilitate social inclusion, social justice and social development.

9. Conclusion

The science of our times is a natural result from the reductionist, atomistic approach handed down through the ancient Greek traditions following Aristotelian logic and is perhaps one of the reasons why there has been little change (from a single perspective) in the century old question posed by Flexner.

Poetry, a form of self-expression and communications which has no restrictions and is an interplay between poet and reader, working with words, images, and rhyme, allows the parties to co-create meaning. In this case, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and that is where one finds “meaning”, and that meaning is a result of the different perceptions “given a voice”.

Where one approach sometimes falls prey to the treatment of symptoms, the latter, results in treating the whole, by identifying meaning (and root cause), and in relation to the original question posed by Flexner, the former approach, led one away from a conclusive answer.

This paper brings us back in line with the true definitions of social work by using an Advanced Relational Meaning System (“A.R.M.S.”) introduced in this paper to operate within the social work framework to the previously mentioned conceptions of social inclusion, social justice, social welfare, social organisation, and social development.

This cross-cultural, global and local social development framework provides an indication of the essence of meaning systems from micro-organisms to supra-national organisations that enable You and Yours, and if the role of the social worker is to help find meaning and enable people to live a fuller life, then the century old question has been answered.

This article releases initial findings of an instrument that reduces initial time required to improve client centred Social work and identification of the underlying patterns of human interactions.

Further research is appropriate to establish the connections with human consciousness and coping impacts on and self-esteem as contributors to effective performance.

The examination of prior research literature indicates interest in the construction of new instruments applying biomorphic and neuromorphic insights into the functions and structures of human changes and choices.