Epidemiological, Clinical and Etiological Aspects of Non-Traumatic Comas in Children at the Pediatric Teaching Hospital in Bangui ()

1. Introduction

Non-traumatic coma is a medical emergency that requires a rapid diagnostic approach, simultaneously with emergency resuscitation measures [1]. Related to a failure of the pontomesencephalic ascending reticular formation, Coma is defined as the more or less complete and prolonged loss of consciousness and of the ability to relate to others, associated in severe forms with vegetative and metabolic disorders [2]. In children, this disorder occurs while their nervous system is still developing. There is therefore a significant risk of compromising the normal acquisition process, especially if the Coma occurs and is prolonged before the age of two, with deleterious effects that can be felt until the age of six or seven. [3] Although Coma is empirically a frequent reason for admission to the Neurological Intensive Care Unit, with approximately 180,000 to 250,000 people hospitalized per year [4], there are few African studies devoted to its epidemiological, etiological and prognostic characteristics in the pediatric neurological setting [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]. In a few published series regarding non-traumatic comas in children, the incidence is of the order of 30 per 100,000 children, with a peak of 160 per 100,000 children before one year of age and 40 per 100,000 children between 2 and 16 years of age [10] [11]. A fundamental step in management is to determine etiology [12]. Infection is the most frequent cause of non-traumatic comas in children worldwide, with, depending on the region, the predominance of severe P. falciparum malaria and bacterial meningitis [13] - [22]. Secondary causes are metabolic and toxic [10]. In 15% of cases, no etiology is found. Mortality depends on age and etiology [10] [23] [24]. Several factors determine the prognosis of a non-traumatic coma. [25]. These factors are associated with the context of developing countries, the delays in care, the lack of social security system and the inadequacy of the technical platform that represents indicators of access to care [1]. The management of Comas is relatively difficult due to the complexity of the etiology [25]. This complexity and the lack of publications on non-traumatic coma in children in the Central African Republic led us to conduct this study. The aim is to improve the hospital management of children with non-traumatic coma. The objective of this work was to describe the epidemiological and clinical aspects of non-traumatic comas in children in Bangui.

2. Methodology

Our study took place at the Pediatric Teaching Hospital in Bangui (CHUPB), the only referral hospital and the only structure specialized in the care of children with vital distress in Central African Republic (CAR). It receives children from birth to 15 years-old, coming from home or referred from a public or private health center in the capital and the provinces. This was a single-center cross-sectional study, covering the period from January 1 to June 30, 2021. We included in the study, after informed consent of the parents or guardians, children from 1 month to 15 years of age, who consulted the emergency room of the CHUPB with a Glasgow score lower than or equal to 8 in a context of absence of traumatism. We did not include in the study children with a traumatic Coma, those admitted for a nontraumatic Coma and whose entry examination noted a GCS score greater than 9, and children who had received a sedative before the GCS score was recorded. For each child included, we collected data related to epidemiological (age, sex, place of residence, origin), anamnestic (reason for hospitalization, time of consultation or hospitalization, symptoms presented before hospitalization, mode of onset of Coma, treatment instituted before admission and history of the child), clinical (general signs, physical examination signs) and paraclinical (Biological: CSF (Cerebrospinal fluid), thick drop (GE), CBC, blood ionogram, creatinine, transaminases, ketonuria, 24-hour proteinuria, Blood culture, capillary blood glucose and Morphological: chest X-ray, transfontanellar ultrasound, abdominal and cardiac ultrasound). The data collection started with authorization from ethical committee. Obtaining of the research authorization and the favorable opinion of the ethical committee of Bangui; then we introduced ourselves to the head of the intensive care unit of the hospital. After explaining the purpose of our work, we were given access to the children’s medical records, to the parents or legal guardians, to the wards, and to the hospitalization records. Confidentiality was also maintained. There was no conflict of interest. Thus, for each child, the different data collected were entered and analyzed through the statistical software SPSS 20.0. For word processing we used Microsoft Word 2003. The statistical test used was Pearson’s chi2, any p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the Odds ratio was calculated with a 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological Data

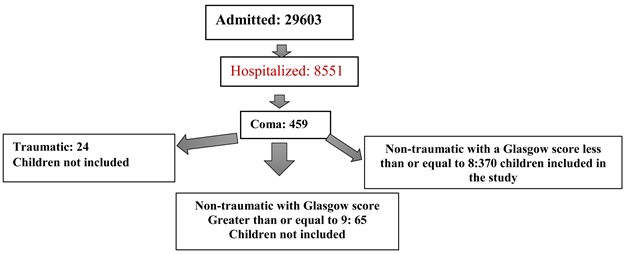

Of the 8551 children hospitalized during the study period, 459 were hospitalized for Coma, giving a rate of 5.36% of hospitalizations. For this study, we retained 370 children, i.e., a hospital frequency of 4.32% (see Diagram 1).

3.2. Sex, Age and Place of Residence

The infants and children were divided into 57.5% (n = 213) boys and 42.44% (n = 157) girls, with a sex ratio of 1.35. The mean age of the patients was 2.95 ± 2.21 years with extremes [1 month - 14.8 years] and a median of 2.58 years. A predominance of children under 5 years of age 88.03% (n = 322) was noted versus

Diagram 1. Flow of children.

12.97% (n = 48) for those over 5 years of age. The children lived in the urban area of Bangui in 72.71% (n = 269) of cases and in the rural area in 27.29% (n = 101).

3.3. Place of Origin and Period of Hospitalization

They came from home in 62.97% (n = 233) of the cases and were transferred from health facilities (FOSA) in 32.98% (122%) of the cases and from a medical office in 4.05% (n = 15).

From one month to another, we observed a case fatality of 6.39% (71/1111) in January, 4.37% (149/1120) in February, 6.42% (74/1152) in March, 4.25% (66/1550) in April, 3.11% (n = 49/1574) in May and 3.13% (n = 61/1945) in June, as shown in Figure 1.

3.4. Children’s History and Pre-Hospital Drug Treatments

A previous Coma episode was found in 30 (8.11%) children: 22 cases (5.94%) all following neuromalaria, seven cases (1.89%) following intoxication (herbal decoction) and one case (0.27%) of diabetic ketoacidosis. A previous history was found in 29.18% (n = 108) of children. These were severe acute undernutrition 31.48% (n = 34/108), HIV infection 19.44% (n = 21/108), sickle cell disease 17.59% (n = 19/108), diabetes 13.88% (n = 15/108), nephropathy 8.33% (n = 9/108), cardiovascular disease 1.35% (n = 5/108) and epilepsy 1.35% (n = 5/108). Prior to admission, 86.48% (n = 320) of the children have received treatment. It was self-medication 58.45% (n = 187/320) and medical prescription 41.55% (133/320). The type of pre-hospital treatment was antipyretic 35.62% (n = 114/320), traditional herbal medicine 23.75% (n = 76/320), Antibiotic 19.79% (n = 62/320) and Anti-malarial 18.75% (n = 60/320) and corticoid 2.5% (n = 8/320).

3.5. Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Parental History

The parents had a primary education level in 33.24% (n = 123) of cases for the fathers and 40.82% (n = 151) for the mothers. They had a mean age of 27.7 ± 2

![]()

Figure 1. Distribution of patients according to months of hospitalization.

years with extremes of [19.2 - 67 years] for fathers and 22.3 ± 4 with extremes (16.9 - 52 years) for mothers.

Thirty (8.10%) children were fatherless, versus 15 (4.05%) motherless and 5 (1.35%) had their both parents died. A previous history was found in 12.43% (n = 46) of cases in fathers versus 17.83% (n = 66) of mothers. HIV infection was found in 30.43% (n = 15) of fathers and 37.87% (n = 25) of mothers, diabetes in 26.08% of fathers versus 16.66% of mothers, hypertension in 26.08% of fathers versus 12.12% of mothers, tuberculosis in 8, 69% versus 12.12% of mothers, stroke in 6.52% versus 3.03% of mothers, heart disease in 4.54% of mothers, epilepsy in 4.54% of mothers, chronic liver disease in 3.03% of mothers and psychiatric pathology in 3.03%.

3.6. Consultation Time - Mode of Onset of Coma and Reason for Consultation

The average consultation time was 2.91 ± 1.8 days, with extremes of [0.7 - 17.9 days]. It was less than two days in 41.35% (n = 153), between 2 and 5 days in 26.75% (n = 99), greater than or equal to 5 days in 31.90% (n = 118). The mode of onset of Coma was abrupt in 34.05% (n = 126) and progressive in 65.95% (n = 244). Symptoms associated with Coma were fever 86.48% (n = 320), convulsion 80% (n = 296), skin pallor 33.24% (n = 123), restlessness 25.94% (n = 96), breathing difficulties 18, 64% (n = 69), fixed upward gaze 10% (n = 37), headache 7.29% (n = 27), rash 6.75% (n = 25), polyuria associated with polyphagia and polydipsia 6.75% (n = 25), neurological deficit 4.32% (n = 16). Diarrhea was associated with vomiting in 13.51% (n = 50) of cases, isolated in 3.24% (n = 12). The reasons for consultation are shown in Figure 2.

3.7. Clinical Data

Temperature measurement revealed fever in 80.54% (n = 298) of children, normal temperature in 15.95% (n = 59) and hypothermia in 3.52% (n = 3.59). Tachycardia was noted in 88.91% (n = 329) of cases, bradycardia in 8.38% (n = 31). One hundred and seventy-nine of children (48.37%) had saturation < 95% versus 51.63% (n = 191) with saturation ≥ 95%. Fifty-three (14.33%) children had hypotension versus 0.54% (n = 2) for hypertension. The Glasgow score was between 8 and 6 in 52.45% (n = 194) of cases, i.e., essentially a stage II Coma. This score was between 5 and 4 in 42.95% (n = 159), i.e. a stage III Coma, and

![]()

Figure 2. Distribution of children according to the main reasons for consultation accompanying the Coma. *The same child could have one or more symptoms.

less than 3 in 4.60% (n = 17), i.e. a stage IV Coma. The distribution of general signs is shown in Table 1. Undernutrition was noted in 18.64% (n = 69) of cases. Wasting was noted in 14.05% (n = 52) of cases and weaning in 4.59% (n = 17) of cases. Pupil anomaly was found in 35.67% (n = 132) of cases. These were bilateral mydriasis in 45.45% (n = 60/132), tight myosis in 37.12% (n = 49), and anisocoria in 17.43% (n = 23).

3.8. Signs of Examination

Physical examination noted splenomegaly in 51.08% (n = 189) of cases, cutaneous-mucosal pallor in 17.02% (n = 63), meningeal syndrome 16.75% (n = 62), skin recoloration time greater than 3 seconds 15.67% (n = 58), severe respiratory distress syndrome 12.97% (n = 48), coldness of the extremities 12.7% (n = 47), hepatomegaly 11.08% (n = 41), rales of bronchial congestion 10.54% (n = 39), Attitude in decerebration 7.02% (n = 26), Attitude in decortication 6.21% (n = 23), crepitus rales 5.13% (n = 19), persistent skin folds 4.86% (n = 18), dry mouth 4.86% (n = 18), eye ring 4.32% (n = 16), opisthotonos 3.78% (n = 14), neurological deficit 3, 24% (n = 12), cyanosis 2.97% (n = 11), systolic murmur 2.16% (n = 8), jaundice 1.62% (n = 6), gallop sounds 1.35% (n = 5), lower extremity edema 1.35% (n = 5), ascites 0.81% (n = 3), bladder globe 0.54% (n = 2). The signs of examination are recorded in Figure 3.

3.9. Paraclinical Data

The rapid diagnostic test for malaria was performed in all cases upon admission and was positive in 58.37% (n = 216) of patients. a thick drop was performed in all children and was positive in 29.72% (n = 110) of cases. The average parasite density was 1005.3/mm3 with extremes [80 - 7900/mm3]. Blood glucose was performed at entry in all cases. The mean blood glucose level was 96.8 ± 5.6 mg/dl with extremes [Lo - 757 mg/dl]. Glycemic abnormality was noted in

![]()

Table 1. Distribution of children according to general signs.

![]()

Figure 3. Distribution of children according to examination signs.

45.94% (n =201) of cases. It was hypoglycemia in 55.72% (n = 112) of cases and hyperglycemia in 44.27% (n = 89) of cases. A blood count was performed in all patients. The mean white blood cell count was 6998.5/mm3 with extremes (109 - 97,000/mm3). The white blood cell count was normal in 44.86% (n = 166) of cases, hyperleukocytosis in 44.86% (n = 166) of cases and leukopenia in 10.28% (n = 38) of cases. The mean hemoglobin level was 7.8 g/dl with extremes (1.9 - 14.4 g/dl). The hemoglobin level was normal for age in 54.86% (n = 203) of cases and below 5 g/dl in 14.06% (n = 52). The mean platelet count was 140,000.67/mm3; extremes (1100 - 420,000/mm3). The platelet count was greater than or equal to 150,000/mm3 in 48.64% (n = 180) of cases, 100,000/mm3 to 149,000/mm3 in 25.67% (n = 95) of cases, 50,000/mm3 to 99,000/mm3 in 9.18% (n = 34), 20,000/mm3 to 49,000/mm3 in 8.37% (n = 31), and less than 20,000/mm3 in 8.11% (n = 30). The blood ionogram performed in 42.16% (n = 156) of patients noted an abnormality in 40.38% (n = 63) of cases. The mean natremia was 136 ± 11.9 mmol/l, extremes 112 - 165 mmol/l. Isolated hyponatremia was noted in 30.15% (19/63) of cases and isolated hypernatremia in 7.93% (5/63). The mean kalemia was 3.7 ± 2.28 mmol/l extremes (1.7 - 7.8 mmol/l). Isolated hypokalemia was noted in 7.93% (5/63) of cases and hyperkalemia in 14.28% (9/63). Simultaneous presence of hypernatremia and hypokalemia was noted in 4.76% (3/63) of cases. The simultaneous presence of hypernatremia and hyperkalemia represented 9.52% (6/63) of cases and hypokalemia-hypernatremia in 25.39% (16/63) of cases. Creatininemia was performed in 115 (31.08%) patients with a mean level of 64.6 ± 3 micromole/l. The mean glomerular filtration rate was 133 ± 27 ml/min/1.75m2. A decrease in glomerular filtration rate was noted in 55.65% (64/115) of cases. Renal failure was mild in 43.75% (28/64) of cases - moderate in 32.81% (21/64) of cases - pre-terminal in 15.62% (10/64) of cases and end-stage in 7.81% (5/64) of cases. Of the 115 (31.08%) cases of International Normalized Ratio respirated (INR), hepatocellular insufficiency was noted in 52.17% (60/115) of cases. An acid-fast bacillus (AFB) test in sputum was performed in 6.75% (n = 25) of cases and was positive in two (8%) children. GeneXpert was performed in 7 (1.89%) children. The result was positive in two cases (28.57%). Bilirubinemia was performed in 155 (41.89%) patients, with a mean level of 4.79 ± 2.3 extremes (0.6 - 17.3 mg/dl). Lumbar puncture was performed in 20.54% (n = 76) of cases. The appearance was clear in 77.63% (n = 59), cloudy in 18.42% (n = 14) and purulent in 3.95% (n = 3). The mean glycorrhaphy/blood glucose ratio was 37.5 ± 2.1; extremes (21.34 g/l - 1.7 g/l). Normo-glycorachy was noted in 68.42% (n = 52) of cases, hypo-glycorachy in 30.26% (n = 23), and hyper-glycorachy in 1.32%. Mean proteinorachy was 0.91 ± 0.3 g/l; extremes (0.20 - 1.5 g/l). Hyperproteinorachia was noted in 23.68% (n = 18) of cases. Pleocytosis was noted in 35.52% (n = 27) with a mean value of 434.6/mm3. The culture had isolated germs in 14.47% (n = 11) of cases. These are: Streptococcus Pneumoniae 72.72% (n = 8), Neisseria meningitidis 18.18% (n = 2) and Haemophilus influenzae 9.09% (n = 1).

3.10. Imaging

Seventeen (4.59%) children had a chest radiograph. An abnormality of the X-ray was noted in 64.70% (n = 11/17) of cases. Cardiomegaly was noted in 54.54% (n = 6/11) of cases and diffuse opacities in 45.46% (n = 5/11) of children. Abdominal ultrasound was performed in 7.02% (n = 26) of children. An abnormality was noted in 69.23% (n = 18/26) of cases. It was hepatosplenomegaly in 72.22% (n = 13/18), isolated splenomegaly in 23.07% (n = 3/18) and hepatomegaly associated with deep adenopathy in 11.12% (n = 2/18). Cardiac ultrasound was performed in 8 (2.16%) children and revealed normal results in all cases.

3.11. Etiological Data

An etiology of Coma was found in 165 (44.60%) of children. It was neuromalaria in 66.66% (n = 110) of cases, diabetic ketoacidosis Coma in 12.12% (n = 20), bacterial meningitis in 6.66% (n = 11), hypovolemic shock in 5.45% (n = 9), status epilepticus in 3.11% (n = 5), multifocal tuberculosis in 2.4% (n = 4), uremic encephalopathy in 1.8% (n = 3) of cases and hypoglycemia on severe emaciation in 1.8% (n = 3) of cases. Diagnostic confirmation using a set of arguments represented 55.40% (n = 205) of cases. These were sepsis 19.51% (n = 40), meningitis 16.09% (n = 33), meningoencephalitis 15.60% (n = 32), encephalitis 15.12% (n = 31), post-phytotherapy intoxication 6.82% (n = 14), neuromeningeal tuberculosis 6.82% (n = 14), hemolytic uremic syndrome 1.48% (n = 3), brain abscess 1.48% (n = 3), sickle cell stroke 0.98% (n = 2) and intracranial expansive process 0.98% (n = 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Epidemiological Data

Hospitalization frequency

Non-traumatic Comas are a relatively frequent pathology: each year approximately 180,000 to 250,000 people are hospitalized for Comas [4], including 30 per 100,000 children per year for non-traumatic coma [10]. In our series, the hospital frequency was 4.32%. This hospital frequency is close to that of two African studies carried out in Togo (5.4%) [17] and Nigeria (5.9%) [15]. On the other hand, another African study found a frequency approximately four times higher (16.3%) than ours [20]. Lower frequencies than Bangui (1.67%) were recorded in the Middle East by Khaliq in Yemen [26] and in India (2%) by Vykuntaraju Gowdaa [27]. The differences between these studies and ours are probably due to the inclusion criteria; only patients with severe disorders were considered in our study.

4.2. Age and Sex

In our study, the mean age of the children was 2.95 ± 2.21 years, similar to that found by Khodapanahandeh in an Indian study [23] and Khaliq in Yemen [26]. On the other hand, a higher mean age was found by Anık (5.87 ± 5.72 years) [28], Asse (4.47 years) [20], Saba (3.75 years) [29] and by Brisset (3.58 years) [30]. Coma mainly affects children under five years of age (88.03% in our series), a fact known in Africa [31]. Mwangani found similar proportions (88%) in Kenya [32]. Other African studies found lower proportions than ours: 57.7% in the Ivorian study [20], 62.5% in the Nigerian study [22], 70% and 76% in Togo [17] [33]. The Asian continent records lower proportions than the African continent and ours: 40% in India by Biradar [34], 42% in India by Nayan [35] and 47.2% in Arabia by Ali [36]. Early childhood is more affected among the 322 children under 5 years old in our series with 54.59% (n = 202). This observation corroborates that of Wong in a general population-based study in England, who stated that the age-specific incidence is significantly higher in the first year of life (160 per 100,000 children per year) [10]. The predominance of under-5 s is probably due to a greater susceptibility of this age group to infections, martial deficiency in some parts of the world, malnutrition and poor socio-economic conditions, and lack of vaccination [37]. In addition, it would certainly be related to the main etiologies of non-traumatic coma in countries south of the Sahara, among which malaria and purulent meningitis are noted. This hypothesis is reinforced by the WHO observation that severe malaria is particularly frequent in children aged six months to six years [38]. A male predominance is noted in our series with a sex ratio of 1.35. This same male predominance is found by several authors [16] [17] [39] [40]. On the other hand, a Yemeni and Beninese study noted a female predominance [23] [30]. A British study conducted in the general population concluded that the incidence of non-traumatic coma in children is not associated with gender [10]. This finding is consistent with that shown in the Seshia study [37].

4.3. Origin of the Children

The majority of children came directly from their homes (62.97%), without using another health facility. This finding was also made in two previous studies conducted in the intensive care unit of the CHUPB on severe malaria: finding respectively 77.35% and 68.48% of children coming from their homes [40] [41] [42]. The choice of parents to bring sick children directly to the national pediatric referral service, without respecting the health pyramid, would be related to the lack of information on the access to care circuit as well as to the fact that treatment is provided free of charge at the CHUPB.

4.4. Treatment before Hospitalization

Treatment before hospitalization was administered in 86.48% (n = 320) of cases, of which 58.45% (n = 187/320) were self-medication and 59.35% (n = 111) were obtained over the counter. The use of phytotherapy before hospitalization was observed in 40.65% (n = 76) of cases. Our results are similar to those of an Ivorian study carried out by Asse who noted that prehospital treatment was administered in 68.3% of cases, 39.8% of which were self-medicated [20].

Self-medication is explained in most developing countries by the easy availability of over-the-counter drugs. However, the population also resorts to herbal medicine inherited from ancestral cultures in order to avoid long waiting lines in public institutions and to save money. The use of herbal medicine is also facilitated by the proximity of the population to traditional healers.

4.5. Duration of the Symptomatology (Consultation Time)

The average consultation time is long. Longer consultation times are found in Ivory Coast (3.6 days), Benin (4 days) and Congo Brazzaville (8 days) [13] [20] [30]. Admission delay to the pediatric ward can be explained by the use of phytotherapy, the efficacy of which is not always proven, and to self-medication, which is often inappropriate because of the quality or the inappropriate dosage. Diaby in Abidjan reported that patients are first treated by traditional practitioners before coming to the hospital at a very advanced or late stage. [43].

4.6. Examination Signs

In our study fever is the constant symptom 86.48% (n = 320), making the non-traumatic coma of the Central African child a febrile pathology. Convulsions were the second most common symptom (80%). Beninese and Malaysian studies have reported the same symptoms, but in different proportions [30] [40]. The predominance of neurological symptoms in a febrile context suggests neuromalaria in malaria-endemic areas until proven otherwise. Its main differential diagnosis—bacterial meningitis—should be systematically run out or treated presumptively in case of contraindication of lumbar puncture [44].

4.7. Paraclinical Examinations

African and Asian countries classified as “low-income” by the World Bank [45], often have insufficient technical facilities. Thus, virological research in cerebrospinal fluid as well as in blood, and the realization of multiple blood cultures in search of an etiology are often not accessible. The same is true for neuroradiological explorations (CT and MRI). Routine examinations (blood count, blood sugar, thick blood drop, malaria RDT)—at the hospital’s expense in our study—are systematically performed in all children at admission. On the other hand, examinations that are the responsibility of the population, such as blood cultures, fundus and CT scans, are often not performed. The CSF study after lumbar puncture, which is expensive and obeys certain rules, including the absence of signs of intracranial hypertension, is performed in 20.54% (n = 76) of cases.

4.8. Etiologies

At least 3 out of 5 children (55.40%) do not have paraclinical confirmation of the etiology of the Coma until death or discharge from intensive care. The lack of confirmation of the etiological diagnosis in non-traumatic coma in children is still present in middle- and high-income countries despite a good technical platform [45]. In the United Kingdom, for example, 14% of etiologies remain unknown in a general population study [10]. This was observed in 8.2% and 6% in two Iranian studies [23] [46], in 8% in a Yemeni study [26], in 4.76% in Benin [30] and 4% in Ivory Coast [20]. These proportions of Coma without etiological confirmation reinforce the findings of the Joanna Briggs Institute that signs from different causes are partly responsible for diagnostic errors in the clinical investigation of nontraumatic Coma in children in resource-limited countries. The limited resources make a proper differential diagnosis contribute to this. Paradoxically, in areas of high malaria endemicity, high parasitaemia in some children evolves without symptoms [45] [47]. In any case, based on the practical classification of etiologies of Coma in children according to three categories: infectious or inflammatory, structural, metabolic or toxic [48], in our study, non-traumatic comas are mainly due to central nervous system infections (82.43%). Proportions lower than ours are noted in the literature, ranging from 31.4% to 75% [15] [17] [23] [26] [27] [34] [46] [48]. Higher proportions than ours are noted in two studies: 85% by Ibekwe [15] and 93% by Asse [20]. A European study carried out in the United Kingdom [10], on the general population, confirmed infection of the central nervous system as the primary etiology of non-traumatic comas in children (37.80%). Until this UK study, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy and toxic/metabolic effects dominated the causes in Europe [28] [38]. Other studies from other parts of the world confirm this predominance of central nervous system infections [23] [24] [33] [36] [40] [49] [50] [51], while an Egyptian study reports that the most frequent etiology is metabolic (33%), with central nervous system infections (28%) in second place [16]. Metabolic etiology represents the second most common cause of non-traumatic coma in the children in our study 6.21% (n = 23). This etiology is divided into acidotic coma 5.40% (n = 20) and hypoglycemic Coma on acute undernutrition 0.81% (n = 3). Two authors have reached the same conclusion [26] [47]. Taking into account these findings, the importance of infectious etiologies in children is in striking contrast to hospital series for adults where degenerative and cerebrovascular pathologies predominate. [25]. With regard to epilepsy, in Great Britain in the general population and in India, it has been noted that malaise is the second most common cause of non-traumatic coma [10] [23]. In our study, status epilepticus is the 5th most common cause of non-traumatic coma in children. Beyond this discussion related to the groups of etiologies, to what underlying causes are these Comas attached? When the infectious etiology is confirmed, Cerebral malaria is evoked in 29.72% (n = 110) of cases, followed by bacterial meningitis in 2.97% (n = 11).

As in our series, all the authors from Sub-Saharan Africa are unanimous on the place of malaria as the principal etiology of non-traumatic coma in children, with proportions varying according to whether the study is carried out in a holo-endemic zone, where the prevalence rate of P. falciparum parasitaemia exceeds 50% for most of the year in children aged 2 - 9 years or in a meso-endemic area, where the prevalence rate of P. falciparum parasitaemia is between 11% - 50% for most of the year in children aged 2 - 9 years or in hypo-endemic areas where the prevalence of P. falciparum parasitaemia is 10% or less for most of the year in children aged 2 - 9 years [38]. Thus, the prevalence of neuromalaria as the main etiology of nontraumatic Coma varies in Sub-Saharan Africa from 44.4% to 90.8% [19] - [24] [30] [40]. The low proportion found in our work compared to other studies is related to the fact that, in our series, Comas with GCS between 12 - 9/15 are excluded including those who received diazepam after convulsion in the health facilities before their transfer to the CHUPB. The highest prevalence of African studies is that of the Ivory Coast (90.8%) [20]. According to the author, this excessive rate is justified by the fact that cases of viral encephalitis or neuromeningeal hemorrhage could have been included [20]. The author supports the fact that in malaria endemic areas, a positive thick blood smear does not exclude the possibility of other diseases, as some healthy children have a positive parasitology [20]. Finally, it confirms, as is the case in our study, that the inadequacy of the technical platform did not allow virological research in the cerebrospinal fluid as well as in the blood [20]. It is therefore easier in countries with limited resources to conclude that neuromalaria is the cause of a non-traumatic coma in a child because other etiologies, especially viral, are not investigated. The evocation of a co-infection seems risky in these conditions. In our study, as in that of other African authors, meningitis comes in second place with low proportions [13] [17] [20] [24]. Different infectious agents predominate in Coma in children in other parts of the world, depending on the geographical region where the study is carried out. Two Indian studies, for example, found a higher frequency of viral encephalitis, bacterial meningitis as the main cause of nontraumatic Comas in children and rarely malaria [24] [52]. In Japan, measles virus, herpes simplex and rubella are predominant in non-traumatic comas of children [22]. In Yemen, the most frequent causes of non-traumatic coma in children are viral encephalitis, bacterial meningitis, and cerebral malaria [26]. For the Brazilian study the main etiology of Coma is meningoencephalitis [53]. The same is true for the Indian study by Ikhalas [46]. For the Iranian study the most frequent causes of Coma were cerebral malaria, meningitis and encephalitis [21]. Bacteriological culture of CSF, which should be systematic, is only performed in a few cases at the Institut Pasteur in Bangui. This reality does not allow the international consensus on the actions to be taken in the case of any unexplained Coma to become effective [6]. Moreover, the same consensus stipulates that when faced with a clear CSF - 77.63% (n = 59) of LP cases in our study—one should also think of tuberculous meningitis or listeriosis [6]. Infection is thus the most important cause of non-traumatic comas in children worldwide, with the predominance of a different type of infection depending on the region: severe P. falciparum malaria and bacterial meningitis.

5. Conclusion

The present study has shown that non-traumatic coma is a public health problem among children in the Central African Republic because of its high prevalence. Infectious causes, including malaria, metabolic and toxic causes are the most observed. It is most common in children under five years of age from parents with low social status. Accurate diagnosis of the etiology of nontraumatic Coma in this study is difficult by the overlapping clinical presentation, and limited diagnostic resources (205 unconfirmed etiologies during the study period). The endemicity of malaria was a barrier to the recognition of other etiologies. In addition to the need for intensive care resources, there is a need for more advanced diagnosis through access to molecular biology and appropriate imaging. The reduction of its frequency requires, among other things, the reinforcement of the national monitoring malaria program, the reinforcement of the extended immunization program, and the awareness of traditional drug intoxication. The strengthening of the technical platform constitutes the other axis of prevention.

6. Study Limitation

Non-traumatic coma is a very common medical emergency in the pediatric setting. The aim of this study was to determine the frequency and to describe the clinical and paraclinical aspects of children with non-traumatic coma hospitalized in the intensive care unit of CHUPB. The study had a number of pitfalls related to the inadequacy of the technical facilities in the CAR, which did not allow for the performance of certain examinations, including MRI due to its absence or CT scans due to their high cost, which was not accessible to all and transfontanello ultrasound. It was also impossible to perform certain analyses, such as CSF PCR and blood cultures, within the CHUPB. However, this study has the advantage of being carried out in the only referral hospital for the care of children in the CAR. This constitutes sufficient coverage of the child population of Bangui. In addition, the methodological rigor and sample size increased the reliability of the statistical analysis.