The Africanization of the European Art: A Short History and Its Contemporary Evolution (19th-21st Centuries) ()

1. Introduction

At the end of the 19th century the first answer to the crisis of Positivism was Decadentism, officially started in France in 1883, with the publication of the sonnet Languer in Le Chat Noir by Verlaine. It marked the transition from an age of rational certainties to another characterized by irrationalism, return to spirituality, symbolism and all what the most profound and hidden the human soul had. The group of poets gathered around the figure of Verlaine was called derogatorily “decadent”, a definition which was assumed with a positive meaning by these artists, who founded in 1886 the magazine Le Décadent, a sort of official organ of the new movement (Mondet, 2006). In philosophy, figures like Bergson helped to provide a theoretical base for the new decadent movement: according to this French philosopher, the rational analysis would be only one of the forms of consciousness (and not even the deepest). It crystallizes and simplifies reality, whereas the intuition proceeding from the profound Egoallows a better knowledge of the man as well as the environment that surrounds him (Ribeiro, 2013). In France, besides Bergson it is necessary to mention the work of Proust on the lost time. Here, once again, memory and search for a past time will characterize the interior path of the man.

Thanks to this aesthetic and philosophical context, French plastic and pictorial arts registered an interesting evolution between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Such process was due in large part to the contamination with a part of the art traditionally considered as exotic and inferior: the African art. As we try to show in this article, such encounter will cause an acceleration, in terms of innovation, inside the Paris School, whose consequences will last until today.

2. The European “Discovery” of the African Art

The first museum of exotic, or colonial art was opened in Paris in 1855 (Musée permanent des colonies), followed by the more famous Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadero (1878), frequented by artists as Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Brancusi and Modigliani. These museums represented a personification of the colonial vision of a vast and powerful empire as that of France in Africa. The opening of these museums was the climax of an attitude towards Africa and the Africans which had started and spread in France (and all over the Europe) since the conquests of Egypt by Napoleon, in 1798. For his expedition in the lands of pharaohs, Napoleon had taken with him 167 researchers, scientists and artists, who formed the Commission des Sciences et des Artes. It aimed to valorize the historical aspects of this military conquest. In 1809 24 volumes of the Description de l’Égypt written by Denon were published, in accordance with a plane, which associated the imperial megalomania of Napoleon with his cultural ambitions (Lechot, 2005).

This publication, together with the deciphering by Champollion, in 1822, of the Egyptian alphabet showed an illuminist inspiration. The goal was to know what Egyptian civilization really was, overcoming the romantic and imprecise travel reports written by several adventurers. The romantic tradition had already entered a crisis thanks to the work of Volney. He lived in Egypt and Siria for three years, writing a realistic book and leaving no space for fantasy (Pellegrinelli, 2007). In the pictorial arts too, Egyptomania registered an exponential increase during the 20th century, with representations of different artists on various subjects, but always in relation to Egypt and the Near East (Monneret, 1989).

Beyond the informative intentions of Volney and Denon, the Egyptian “myth”—and thus the “African” myth—continued to nourish the artists’ and poets’ aspirations and the need of evasion from an oppressive reality, recovering another myth, that of the “good savage” of Rousseauian memory. Philosophers as Bergson and Proust contributed to rekindle this myth, although indirectly.

This interpretative line of the African culture and art, although idealized, was early subjugated from another tendency, inspired by the colonialist and racist propaganda, spread out all over the Europe. The edification of a collective imaginary inspired by the theories of the scientific racism, as those of Cuvier on the polygenism of human races, of Gobineau, De Lapouge and finally Renan during the Third Republic (Stanchina, 2019) left few doubts and spaces: all what came from Africa was biologically inferior, and as such it was to be treated. Phenomena as the “human zoos” composed by Africans (including children) locked up in cages like monkeys, representations in postal cards, especially feminine (Catone, 2011), completely stereotyped, songs of colonial and warmonger inspiration had an enormous impact on the European public opinion, mostly in France, but in Italy too.

3. The Parisian School

In Paris, a group of artists of multiple nationalities, but with an aesthetic and political common sensibility—the deepening of subjects coming from decadentism, symbolism and abstractionism, associated to political tendencies in favor of anarchism and anticolonialism—showed a certain interest for African culture, starting from two points of view: the first one centered on aesthetic, in the footsteps of the legacy left by Egyptomania; the second one of political kind. In France, besides the theories of the scientific racism, an anticolonial and antiracist movement was promoted by anarchists and socialists. Such movements gave an answer to the illustrated almanacs which intended to prove the natural inferiority of the African people, as Le Journal Illustré, L’Illustration, Le Tour du Monde, Le Petit Journal and Le Petit Parisien, emphasising the “sauvagery of customs” of the Africans, in particular during the Dahomey War (1890-1892). The socialist Paul Louis, in 1905, published in Parigi Le Colonialisme, denying the possibility of a non-violent colonialism, whereas the anarchist doctor and deputy, Paul Vigné d’Octon, denounced, in 1907, Les crimes coloniaux de la IIIe République,also published in Paris by Gustave Hervé (Leighten, 1990). In 1905, in France, a Comitéde Protection et de Défense des Indigènes was founded,accompanied with the publication of various texts and pamphlet against colonialism and racist theories. Alfred Jarry, an anarchist friend of Picasso, represented colonialism through satire, sustaining that exactly the hypothetical irrationality, symbolism, fascination would make African culture something higher than the Western one. These ideas surprised the European and French audience (Leighten, 2013).

On the contrary, in other European countries this anticolonial propension was not so accentuated. For instance, in Italy the colonial “enterprises” were characterized by episodes as the defeat of Adua (1896-96) or the Italian-Turkish conflict for the hegemony in Libia (1911-12). So, colonialist (and anti-colonialist) propaganda was not as effective as in France. Nevertheless, in the liberal Italy some institutional initiatives were carried out to improve the colonialist spirit, as the foundation, in 1906, of the Istituto Coloniale Italiano and, in 1912, of the Ministry of Colonies. Some publications also came up in this period, as the Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana, the Rivista Geografica Italiana (Genduso, 2016) and—inspired by eugenetica—in 1913 the Comitato Italiano per gli Studi di Eugenetica was founded by Giuseppe Sergi and Alfredo Niceforo (Martucci, 2021). Anyhow, in Italy the interest towards Africa and consequently towards African art, was weak.

In Paris, African art contributed to a radical change, the overcoming of positivism and materialism. “Exoticism” and “Africanism” were promoted by the artists gathered around the Parisian School. African sculptures began to be treated as real works of art, and not anymore as works of colonized cultures. Thus, if traditionally they were sold for little money at the flea fairs, the artists of the Paris School began to attribute importance to these artifacts. Such tendency went down in history as Primitivism. Such word denotes the interest towards non-Western cultures, including the African and Oceanic ones, as well as the pre-Colombian and those of the Native Americans (Borgogelli et al., 2015). This new interest made artists collectors of African artifacts, so that, at the beginning of the 20th century, rich collections of African art were created.

The colours used by the artists of the Parisian School changed; since these artists did not know the actual meaning that the African artifacts expressed, they introduced something new. It represented an innovation if compared with the accepted aesthetic canons in vogue at the end of the 19th century (Shezi, 2019). In such manner African art gave a fundamental contribution to the development of the artistic avant-garde which characterized the beginning of the 20th century.

African sculptures were used and declined in accordance with the aesthetic sensibility of the artists of the Parisian School. They contributed to the foundation of new movements also out of French, as Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Germany, and Modernism in the United States.

Initially, the Paris School was influenced by painters like Gaugin and Cezanne. Both began their artistic career under impressionistic tendencies (in particular in the case of Gaugin) which aimed to valorize exotic iconographies, taking inspiration directly from their travels to Tahiti and Martinique (Balbino & Fernandes, 2018).

The Spanish painter Pablo Picasso moved to Paris to continue his artistic studies; here, as for many artists of that period, he went to visit the Trocadero Museum, where artifacts of African art were exposed. Since then, Picasso started to collect objects of African art, as masks and sculptures. This interest for African art was shared with his friend-rival Matisse. Matisse exerted a decisive influence on Picasso: Matisse opened the doors of African art to Picasso when he bought, in 1906, a figurine Vili (Congo) from Emilie Heymann and showed it to Picasso. The Spanish painter was instantly impressed by it, as various witnesses remember (Pennisi, w.d.). Nevertheless, the real encounter-confrontation of Picasso with the African art occurred when he visited, for the first time, the Trocadero Museum. Here, as Picasso himself remembered in a dialogue with Malraux, the first impression was one of rejection, and only on a second time he understood the effective importance of African art for his revolutionary painting:

“The masks were not like any other pieces of sculpture. Not at all. They were magic things. But why weren’t the Egyptian pieces or the Chaldean? Those were primitives, not magic things. The Negro pieces were intercesseurs, mediators; ever since then I’ve known the word in French. They were against everything-against unknown threatening spirits… I understood; I too am against everything” (Huffington, 1998: p. 90).

In the case of Picasso, his encounter with the African art, especially with the statuettes of Gabon and Ivory Coast, influenced the forms of his paintings stiffened, appearing flatterer and simple, and the lines sharper. The first example of this new style is the portrait of Gertrude Stein, a famous American writer and a Picasso patron and friend, together with her brother, Leo.

Pablo Picasso, Retreat of Getrude Stein (1905-1906)

According to the witness of Stein herself (Stein, 1973), her retreat was remade for many times, as Picasso was not satisfied of the result. Eventually, the portrait was not very similar to the real Stein of that epoch (but much more to how Gertrude Stein will appear in her old age): it presented hard traits with black and severe eyes, revealing a clear influence of the African masks that he knew well.

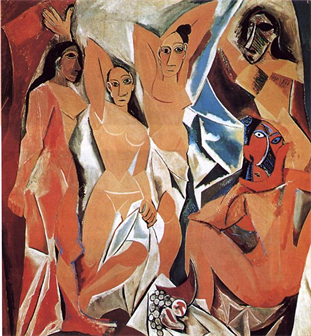

Picasso reached the climax of his “African” period with “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, painted in 1907. The style hinted in the retreat of Gertrude Stein became deeper, and the influence of the African art appeared more explicit. Here, the background is blank, since the simplification must also concern space, with two women who wear masks on their faces. This painting is considered the first example of Cubism, showing in one only dimension—that bidimensional of the canvas—all six views of a subject through the fragmentation of space.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1906-1906

Les Demoiselles would be, “not only unsympathetic to the art and life of established European culture, but its enemy” (Bishop, 2002). Picasso primitivism, based on African influences, is the definitive assault to the culture and to the European aesthetic of that period, in the name of the principle of the authenticity” and against the soothing and complacent European beauty. This painting was defined as the “great manifesto of modernist painting” (Leighten, 2013). The attention and importance of African art in Picasso was confirmed by the fact that he became an avid African masks collector, as the other founder of Cubism, George Braque, witnessed in many circumstances (Pennisi, w.d.).

As Picasso, also Henri Matisse too was not Parisien. He moved to Paris from Cateau-Cambrésis to follow his studies in law. Once abandoned his academic studies, he entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris and afterwards in the atelier of Gustave Moreau, an important symbolist painter. In this atelier he knew André Derain, who introduced Maurice de Vlaminck to Matisse. From this three-person friendship the Fauves were born (Murrell, 2008). The movement of the “beasts” never officially joined and never was formally organized. What was common to these artists were the following elements: one should not paint according to the impression, but according to one’s own interiority; the painting must not be the result of studies or preparation, but it had to be immediate and instinctive, freeing the colour from the real material and emphasising the light (Cricco & Teodoro, 2015).

Matisse began, around 1908, to buy and collect masks and other African artifacts, which influenced his pictorial production. For instance, in 1908 Matisse painted the retreat of his daughter, Marguerite, in accordance with the criterions of the African art, with sculpted and deep features. In the exchanges of paintings that Picasso habitually made with Matisse, it was this painting that Picasso chose.

Henri Matisse, Marguerite, 1907

Islamic art too exerted a considerable influence on Matisse, starting from his visit to the exposition of Islamic art in Monaco in 1910, and even more from his travel in Morocco in 1912-13. If Matisse, together with the other two co-founders of the Fauves, Derain e Vlaminck, was the first to understand the symbolic and revolutionary impact of African art, Picasso fully developed the potentialities of this art. For, he founded a style, Cubism, which changed forever the Western as well as the international aesthetic

In addition to the two major exponents of Modernism, Matisse and Picasso, African art influenced other important artists too, although of lower success.

Amedeo Modigliani (w.d.), an Italo-French painter of Jewish origins, showed from a very young age an inclination for the art, as well as a rebellious temperament, despite his fragile health. His artistic path has always been autonomous and independent. For, in 1902, he decided to leave his hometown, Leghorn, and to move to Florence. Here he came into contact with the free school of the nude, then he continued his studies in Venice. In 1906 he arrived in Paris, where, among the avenues of Montmartre and Montparnasse, he could catch up on the late artistic trends. In Paris Modigliani knew by which he was fascinated. Thanks to Primitivism, he began to integrate the elongated forms of the masks in his paintings, as well as the gouged eyes, which he interpreted as the mirror of the soul. On such basis, he painted pupils to the only person he thought to know, his beloved wife, Jeanne Hèbuterne. Two days after Modigliani’s death at the age of 35 years, she decided to commit suicide, although she was eight months pregnant (Amedeo Modigliani, w.d.).

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeune fille rousse (Jeanne Hébuterne), 1908

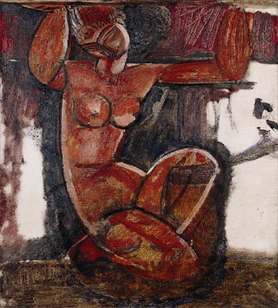

Also in the case of Modigliani, after a first period in Leghorn under the Macchiaioli influence, his experience in Paris changed completely his style and aesthetics. In particular, the acquaintance with the Romanian sculptor Brancusi influenced him considerably: in a first moment, Modigliani was pushed towards the sculpture (which he abandoned, due to health reasons), eventually towards painting. In both the cases, African influence is easily observable in his works, as in Head (1911-12), or in Cariatide, of the same period. Nevertheless, Modigliani never adhered to movements as Cubism, Futurism or other vanguards, remaining an isolated painter.

Amedeo Modigliani, Cariatide, 1911-12

The Romanian sculpture Constantin Brancusi—of poor origins—learnt the simple style of Romanian art, in a first time as a carpenter, studying, in 1898, at the Academy of Fine Arts of Bucharest. Influenced by the reputation of the sculptor Rodin, he decided to leave his country, moving to Munich where he lived 1904, then to Paris. Here, after working for two years at the workshop of Antonin Mercié, he realized his first exposition in Paris in 1906; he refused to work with Rondin, for fear of not gaining the artistic autonomy that he considered necessary. He achieved a great success in the United States, thanks to an exposition in 1913 in the Armony Show Gallery of New York, where he exposed five of his works. Also thanks to Brancusi, the American artistic market opened up to African art, now seen as an actual aesthetic expression.

Brancusi became famous for the net forms and for the direct carving of his sculptures, in a first moment in wood, then in bronze or marble. Although he knew little of the African art, however it influenced him remarkably. As it has happened for Romanian popular art, in the case of African art too he used the woodworking techniques, its symbolism and charm, avoiding a mechanical reproduction of it (Miholca, 2015). Statues like White Negress and Blonde Negress reveal a direct influence of the African sculpture on Brancusi, as the artist himself confessed. This inspiration probably derived from his visit to the Colonial Exposition of 1922 in Marseille, where he could observe an Afro descendant woman, who inspired the above-mentioned artistic subjects, produced respectively in 1928 and 1933.

Constantin Brancusi, White Negress, 1928

The four artists here considered represent a part of the sculptors and painters who, at the beginning of the 20th century, in Paris, were influenced by the African art. They are a paradigmatic example which shows how Africa, with its apparently anonymous art, could contribute to the evolution of the Western and international aesthetic. This encounter permitted to overcome models and artistic values at that time still based on positivism or impressionism, in favor of a form of art more abstract and symbolic. Paris was the center of this aesthetic and cultural revolution, which was also connected with the above-mentioned political aspects and culminated with the Cubism of Picasso and Braque.

4. The African Art as an Absence: Notes on the Italian Case

Differently from what occurred in Paris, in Italy the fruitful encounter between local art and African art did not take place. This is due to cultural as well as to political reasons. Cases as that of Modigliani, illustrated above, or of the Florentin Alberto Magnelli, born in 1888, confirm this scenario. Magnelli, who became an abstractionist and cubist in France, explained the importance of the influence of African art on his works:

“What attracts me most in black art is, first of all, its plastic force and the invention of the forms. Clearly, the meaning of these masks, of these fetiches, of these objects, their use and their charm interest me, but after the sculptural fact itself. As a painter, it is especially the ‘way’ in which these African or Oceanian sculptures have posted or solved powerfully their plastic problems, their expressive mean and the extraordinary richness of invention that they used to work and realize their artifacts, with an illimited time available, without any worries for the hours, the days or the months which they needed” (Revera, 2019).

Around the Thirties Magnelli enriched his collection of African art, living stably in France; at the end of the Sixties this collection counted about 200 pieces. The cases of these two Tuscan artists, Magnelli and Modigliani, show how their professional and aesthetic evolution was possible only thanks to their relocation in France and their contamination with the African art. This would have been impossible in Italy, mainly for the advent of fascism.

Since 1921 the artistic humus in Italy had refused the European vanguards adopting the Stile Novecento (Twentieth Century Style), founded by Sironi, Bucci, Funi, Malerba and others. It is not a coincidence that they exposed their works in 1923 in Milan, in a gallery (the Pesaro Gallery) inaugurated by Mussolini himself. In 1930 this style was assumed as the official one by of fascism (Nacher, 2019). The return to the Renaissance figurativism was applied not only to painting, but also to sculpture, music and literature, thanks to the complacency and promotion carried out by the fascist regime. For, Italy was not predisposed culturally to receive influences of exogenous cultures, least of all those non-European. This cultural climate hindered the crossing with the artistic innovations as in the case of the Parisian School, remaining at the margins of the European and international culture. This is shown, for instance, by expositions abroad promoted by the regime, especially in the Thirties. The most important of them was that of Paris in 1935, with an instrumental use of 11 works of Modigliani, and the exposition of works by painters and sculptors as Boccioni or Martini, with works as Vittoria fascista (Fascist victory) or La Lupa (The She-wolf), completely functional to the ideals and the aesthetic of the regime (Fabi, 2013).

5. The Persistence of African Art Influence and Its Development after the “African” Period of Picasso

African art continued to exert, through Cubism and its main exponent, Picasso, a relevant influence also after the ideal end of his “African” period, in 1909. In both phases of cubism, the analytic and the synthetic ones, this influence was persistent, at least from a conceptual and aesthetic point of view, although not as far as specific techniques of painting are concerned (Pennisi, w.d.); so, Africa did not stop representing a permanent source of inspiration for Picasso. A paint as Guernica (1937) is the best example of it (African Period, w.d.).

In parallel, surrealism—whose Manifesto was published in 1924 by André Breton—also presents significant elements deriving from African or, even more, Oceanian art. Surrealists were mainly interested in African art because of its transgressive potential, which represented a complete rupture with Western categories (Tythacott, 1999). This is confirmed by two surrealist magazines of the Thirties, Documents and Minotaure; the latter published the mission Dakar-Jibuti of Griaule, which will exert an important influence in the Africanist anthropology and philosophy, in France and in general in Europe (Walden, 2021). Also poets like Aimé Cesaire, one of the father of the Negritude, who in 1950 founded the magazine Présence Africaine, belonged to Surrealism (Vergès, 2009).

In the artistic field, painters as Salvador Dalí and photographers like Man Ray also drew from the African art, in continuity with Primitivism, Cubism and the Surrealism itself.

Salvador Dalì, Impressions d’Afrique, 1938

Man Ray, Noire et Blanche, 1926

A different history, but with aesthetic values and contents coming from Africa—initially via Paris School, for instance through the success of Brancusi—will take place in the United States. From the Harlem Renaissance to the jazz, the period which goes from the Twenties to the end of the Prohibitionism, in the middle of the Thirties, is considered as the golden age of the Afro-American history. Thus, other artistic forms will take the scene, as between the Forties and the Fifties, with the Black Abstract Expressionism, with artists as Norman Lewis, Alma Thomas, Beauford Delaney, and—in the second generation—Edward Clark, Sam Gilliam and Howardena Pindell (Harper, 2021).

Portrait of Sam Gilliam in his studio, Washington, DC, 1980. Photo by Anthony Barboza.

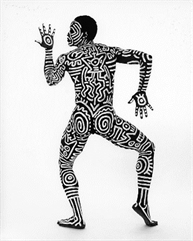

Finally, the birth of the movement Hip-Hop, followed by the diffusion of the street art, with artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and FUTURA 2000, drew its inspiration from sources as African and tribal arts (Bambic, 2014).

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, 1982

Keith Haring, Bill T. Jones body painting, 1983

6. The Leap towards Artistic Subjectivity

The Parisian School and Cubism received and elaborated the influences deriving from African art, which have contributed to the developments of the contemporary aesthetic in various parts of the world, inside and outside Europe. Nevertheless, from the Eighties this scenario changed. The artists of African, Oceanian, Latino-American origins became the front-runners of a new conception and perception of the art. Today, African artists are no longer anonymous, because they express their own, authentic art. From objects molded by diverse movements or artists, African art has become a subject, and the African artists its protagonists. As a matter of fact, various artistic schools were founded in Africa or in other regions outside Europe.

In particular, in Africa, from the Nineties a new generation of artists has been growing. Their path was smoothed by the Paris exposition of 1989, at the museum of the Centre Pompidou. These artists gained fame all over the world. Here is some of them: Rafiy Okefolahan, who paints through tribal symbols for honouring his own origins; Ntombephi Ntobela, the woman leader of the group Ubuhle; Chèri Samba, who has exposed at MOMA, painting scenes of the daily Congolese life, with a good dose of irony; William Kentridge and his charcoal drawings which tell the history of apartheid and of the problematic political situation in South Africa, whereas his compatriot Feni painted the classic African Guernica, with the purpose to represent the violence and the atrocities of apartheid (Callerame, 2021).

Dumile Feni, African Guernica, 1967

The redemption of an endogenous African art is also taking place in other forms, besides those relative to artistic expressions of very high level: the request, by the African countries, of the artworks stolen by the colonizer countries and yet exposed in Western museums. Some European countries (particularly France and Germany) began the process of restitution of the African artworks in their possession. France returned Benin 27 artworks and others, even if fewer in number, arrived from Germany (Steffes-Halmer, 2021). Belgium returned some important artworks to its former colony, the Democratic Republic of Congo, as Germany made with Namibia (Bussotti, 2021). Despite a new attitude towards African artworks in the hands of the former colonizers, some important sculptures remain in Europe, as the Benin bronzes, statues of enormous dimensions and the symbol of the British colonization in Africa, yet conserved at the British Museum of London. Great Britain declined the request advanced by Benin government to have these bronzes back. This position was justified by UK deeming Benin unsuitable to keep such artworks. This shows a colonial attitude after more than 50 years that colonialism ended. Inside the African continent too some agreements were signed in order to return stolen artworks, as in the case of Benin and Nigeria.

7. Conclusion

This research aimed at analyzing how African art exerted a lasting and visible influence in the European and in the international art, starting from the Parisian School and from the new aesthetic and revolutionary canons of Cubism. The cultural and political milieu in France at the turn of the 19th and the 20th century favored the evolution of vanguards which absorbed, through an original elaboration, the African art. On the contrary, in a country like Italy, the cultural and political conditions did not permit to have a meaningful consideration of the African art. Thus, those contaminations which played a decisive role in the Parisian School did not take place.

The importance of the Parisian School was decisive; nonetheless, its artists, Picasso firstly—who when old denied the influence of the African art on his artistic work—manipulated the aesthetic canons expressed by African statues and mask to found new artistic conceptions and styles. In the United States the process of comprehension of African art was evident since the Harlem Renaissance, but it became more conspicuous with Pollock in relation to the indigenous American cultures and, later on, with the Black Abstract Expressionism. In this last instance the Afro-Americans gave voice to their art.

As a matter of fact, the deep comprehension of the art and its transformation from object of study and reflection of the “others” to a new, autonomous subjectivity occurred in the Eighties, when African artists became advocates of their own art. Furthermore, an African artist does not need to move to Europe or the United States to seek recognition or to learn the profession. Today, it is from Africa that these new artists work in accordance with their traditions and their aesthetic sense, proposing artworks and new aesthetic canons, able to interpret a reality, that of Africa, extremely globalized, but also culturally and socially far away from Western world.