An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations from Shipping: The Paradigm of Greece—Part I, from Origin to 1950 ()

1. Introduction

Smith (1776) argued that the wealth of nations comes from production. Mercantilists argued that wealth is equal to the reserves held by the Central Bank. Quesnay (1694-1774)—a physiocrat—who influenced Smith in supporting Free Trade and unrestricted competition—argued that production depends on the productivity of those who work the land.

Smith further argued that wealth can be increased by the division of labor. He opposed the State intervention in the economy and argued that the economy would be regulated by the “invisible hand” of the market. However, he was mistaken in the belief that the market is self-regulating.

We also know that, in addition to GDP, a nation’s wealth, open to global trade, depends on—except governmental spending—exports of goods and services (shipping, tourism, etc.) and on migrants’ remittances. Imports create demand for other nations’ goods and services, except those of capital1, which are beneficial for the importing country.

It is fair to ask whether Adam Smith is still relevant2 to the shipping industry? One of Smith’s basic doctrines, the support of free trade, is still sought by modern Greek shipowners, in the form of free (seaborne) trade, or laissez-faire, which has also been taken up by the EU (Goulielmos, 2022).

Nations must try to substitute imported goods and services with nationally produced ones. It is important to buy or copy the international know-how or create one. Countries that are poor in physical resources, such as Greece or Japan, have to rely on knowledge-based industries. This is not easy, and frequently is obtained only by joint ventures, if at all.

Research creating new products and services should always be pursued, especially by 2022, establishing innovative start-ups, discovering new materials, finding energy-saving techniques, and improving climate. Countries that have no coal, oil, or iron-ore, still have many brains, and good brains can create wealth… (Japan).

Countries that have specialized in shipping have been helped by a number of factors, one of which is shipping tradition. The four leading shipping nations in 2018 all had a rich shipping tradition (Figure 1).

These four global maritime countries brought greater wealth to their countries in the past but also in 2007-2018. In 2020, the Greek-owned shipping reached 341 m dwt (3968 ships over 1000 GRT) and the Greek flag covered, in November 2021, 39.3 m GRT (1834 ships over 100 GRT) (estimated as equal to 21% in dwt of the Greek-owned fleet).

2. The Difficulties Encountered

In writing this paper, we faced difficulties in tracing the historical evidence for Greek shipping. The written history vanishes beyond 3000 BC due to Deucalion

![]()

Figure 1. The 4 top global fleets, 2007-2018. Source: UNCTAD, various yearly editions of the Review of Maritime Transport.

deluge. The evidence we gathered comes mainly from ancient shipwrecks and findings in sheltered caves. Our aim was to trace back the connection of Greeks to the sea, and with islands. We searched the Iliad and Odyssey, knowing that the naval ships were the precursors of commercial ones.

This search addressed three questions: 1) Can shipping supremacy be attributed exclusively to nautical tradition? 2) Can the so-called Greek shipping “miracle” be attributed to the fact that Greece extended over 130 big islands, meaning a powerful influence from geography? 3) Can that miracle be attributed to the fact that only 20% of the land area of Greece was suitable for agriculture?

This kind of research concerning the history of shipping operated by Greeks is, by its nature, dependent on limited sources that are difficult to find. This paper will be successful if it forges only one link in that history, later to be linked with other information, when data may become available. Our particular knowledge of matters related to the Odyssey comes from personal research, which resulted in publishing a booklet in 2009.

3. Aim and Organization of the Paper

The paper addresses one central question: Why do certain nations, and especially Greece, own a considerable number of ships, and derive a serious amount of wealth from shipping, while others do not?

Following the literature review and the methodology section, this paper is structured in seven parts. Part I deals with the Greek nautical tradition and ancient education; Part II deals with three theories that try to explain the superiority of Greek shipowners; Part III deals with the relationship between Greeks and the sea; Part IV deals with Alexander the Great (356-323 BC); Part V deals with the Greek shipping under the Romans; Part VI deals with Greek shipping, 1830-1945; Part VII deals with Greek shipping, 1946-1950. The paper ends with a concluding section.

4. Literature Review

Matsas (2000) is a shipowner who argued that it was in the Aegean Sea where visionary Greek Neolithic (late stone age) people, from the Eastern Peloponnese, traveled in wooden vessels, 10,000 years ago. They were identified as the pre-Hellenes, a nation of sailors. The seaborne trade of obsidian stones, between Milos and a Peloponnese port of Hermione, is recorded as occurring in history in 8000 BC.

Matsas also argued that the Greek merchant marine was re-vitalized in the 1700s, especially in certain Greek coastal cities or islands—trying to mimic Venice and Genoa—including Corfu, Missolonghi (1730, rising to 80 sailing ships by 1770) and Galaxidi (1730, rising to 50 sailing ships by 1764 and 500 later). The Aegean islands were particularly prominent also in shipping: Hydra, Spetzia, Andros, Kasos, Psara and Mykonos. During the Greek Revolution (1821-1830), Greek shipowners turned their merchant ships into warships, where 50 (17%) survived out of 600. Greeks always sacrificed their ships for their freedom.

Polemis (2000), another shipowner, pointed out that Greece could use only a fifth of its land for farming, and, as a result, the sea was the only way out. Long ago, the Greeks were pirates, although this was not illegal at the time.

The value for Greeks to have a strong naval fleet was demonstrated repeatedly in history, especially the 1186 ships they had at their disposal during the Trojan War3 (Table 1), around 2000 BC, and the naval battle of Salamis (480 BC) against Xerxes, King of Persia, 485-465 BC. The Greek General Themistocles, (524-459 BC), argued that Pythia implied the naval ships in her oracle, when she said “the wooden walls would save Athens”. The clever Greek general at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC) was Miltiades, whose bronze helmet is shown (Picture 1).

Picture 1. The bronze helmet of Greek General Miltiades after Marathon battle. Source: Olympia Museum.

Polemis dated the start of the historical period of the Greek merchant marine at 1104 BC, when Greeks (Dorians) from South Thessaly, we believe, returned as a vindictive enemy.

The name “Ellas” (“Hellas” = Greece) first appeared in Achilles’ kingdom, because it was the name of one of his capitals. The people at Dodona (Epirus with an ancient oracle) also used similar names. Greek history records two floods, of which better known is the Deucalion one, during the Bronze Age. The effect of the floods was to sweep away all historical evidence. The flood of Noah (Collins, 2012) is dated around 3000 BC, and it may be possible to identify it with the Deucalion deluge.

In 803 AD, Emperor Nikiforos of Byzantium established the first maritime bank and a Ministry of Mercantile Marine, as well almost all other shipping services (Polemis, 2020: p. 29). After that time, Byzantium started to decline and continued to do so until 1300, and this carried away Greek shipping too.

Polemis (2000: p. 30) argued that during the dominance of the Ottomans over Byzantium, a profession emerged of the “Christian Merchant”. Crete and Cyprus remained in the Venetian hands for some time, and Rhodes and Chios in Genoese hands until 1566. The dominant trade at this time was grain, and the dominant shipowners were Greeks.

North (1968) argued that a decline in piracy and an improvement in economic organization, account for most of the productivity changes observed in ocean shipping between 1600 and 1850. The total productivity index increased sharply after 1840, coinciding with the introduction of steam, we believe. Crew numbers on board reduced over time, meaning that technological progress in shipping was labor- and time-saving.

Bendall & Stent (1988) studied the ship productivity of 562 ships (276 sailing and 286 steamers) calling at the port of Sydney from 1859 to 1919. They concluded that the sail and steam4 technologies grew (in four stages for steam) in an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary way, which is rather unexpected.

Stopford5 (2009) divided the past 5000 years of maritime history into three phases: PHASE 1: The trade in the Mediterranean conducted by Greece, Rome, the cities of Venice, Antwerp, Amsterdam and London, until the 15th century (3000 BC-1450 AD). PHASE 2: The first industrial revolution, in 18th century, took place; new ship designs appeared, and a rise in shipbuilding; the global communications were possible. Suez Canal opened (1865); the Baltic Exchange emerged (1744; see Picture 3 below); colonial structures and the epoch of discoveries characterized this period (1799). PHASE 3: Free trade established; better raw materials discovered; flags of convenience (1800-1950 AD) emerged. Trade etc. controlled by Bretton Woods agreement in the 1940s.

The years when the above took place are between 3000 and 2000 BC and till 1950 AD. The people appeared were (BC): the Phoenicians prior to 300; the Greeks 300; (AD): the Romans 100; the Venice 1000; the Hanseatic League 1400; the Dutch; the English 1735; the North America 1880; and Japan 1950 (Stopford, 2009: p. 6).

Summarizing, a number of maritime nations, over a historical period of 5000 years, emerged, and…disappeared. However, the Greeks, and 11 others, continued their tradition to present, from father to son, over 167 generations. This review is of particular importance because two authors, as indicated above, come from the families of the Greek shipowners.

5. Methodology

This paper stresses the empirical verification of certain initial postulates, and pays attention only to the facts of experience. The causes of wealth creation by certain professions, such as merchants-shipowners, are sometimes attributed to properties obtained during a very remote history or even in myths. In those circumstances it is very difficult to be sure of the historical facts. This research separates the permanent from the temporary, the substantial from the decorative, the reality from the myth, and the things shipowners tell their children when teaching them about ship owning business from the things, they tell journalists.

6. Part I: The Ancient Greek Nautical Tradition and Education

Greeks, since ancient times, conducted sea trade, and established offices, frequently outside Greece, for example along the river Danube. Between 8000 BC and 7000 BC Greeks established trade centers on coasts of the Black Sea in Asia Minor, in South Italy (Sicily) and in South France, right up to Gibraltar and Ceuta, called the “Pillars of Hercules” and marking the limit of the Western World in antiquity.

In Homer’s time, around 2000 BC, Greeks lived in the areas of Thessaly and Peloponnesus; in the valley of Pinios River, in Larissa and on the Malian Gulf (Lamia); in Epirus (especially Dodona) and in Fthiotis, between the rivers Asopus and Enipeas. The Pelasgians were the forefathers of the Greeks, and lived in Dodona (Epirus), Thessaly, Boeotia, Attica and Crete, since 10,000 BC. Moreover, Homeric Greeks lived in 7 islands, which provided ships to fight in the Trojan War (Table 1), and in 24 islands6 mentioned by Homer, including Cyprus.

![]()

Table 1. The 29 Greek provinces, towns and islands provided naval ships for the Trojan War.

Source: Autenrieth, G (Autenrieth, 1890).

There were 29 provinces that supplied ships to form a unified navy to fight in the Trojan War.

In ancient Greek schools, Homer’s Odyssey was the basic textbook, teaching the main principles of an idolatrous education, where revenge was the basic principle, and the unique and principal hero was a king (Odysseus). The king’s wife, Penelope, was the epitome of a faithful Queen. Her son, Telemachus, tried to trace his father, travelling to Pylos and Sparta.

Another favorite story for Greeks, to tell their children, was the Golden Fleece, sought by the Argonauts, under the leadership of Jason, on the ship Argo. The golden fleece was taken from a ram, which bore Phrixus through the air from Thebes. King Aeetes8 hid it in a wood, guarded by a sleepless monster, but Jason took it. Princess Medea helped him. Helle, sister of Phrixus, fell into the sea, the Hellespont, from the back of the ram, holding the golden fleece and using wings.

Greeks from Crete also tell their children stories about the Minoan maritime power, (2400 years BC in Knossos), and about the Minotaur killed by the Athenian Theseus. Crete’s beautiful Ariadne, daughter of King Minos, told him how to get out of the Labyrinth, as Daedalus had told her (Map 1).

![]()

Map 1. The Greek colonies in 550 BC (in red). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greece_and_it%27s_colonies_in_550_BC.jpg; as argued by Stopford (2009: p. 10) by 500 BC Greeks have stablished more than 100 colonies, something emerged also in 8000 BC. Greeks were looking for additional fertile land and sea trade.

Shipowners from Crete took over the trade with Egypt from the Phoenicians, after 1800 BC. Trade of jewelry with people on the Baltic Sea, can be dated back to 1300 BC. Greeks then turned more intensely to look for places to trade outside Greece, in Asia minor, the Black Sea, Africa, Sicily, France and Spain.

The people of the Greek village Phokea, once in Asia Minor, and now in Attica, tell their children how their ancestors established Marseilles (in France), in 600 BC, as well Nice and Antimi. Sailors from Megara established Byzantium, named after their leader, while Spartans established Taranto (Italy) (Taras was their leader), and sailors from Corinth established Syracuse (Italy). Sailors from Chalcis established Naples (Italy), and gave to it their alphabet, on which the Latin one is based. Trade, in those days, implied sea transport. So, Greeks had to be merchants or shipowners or both. They were both.

7. Part II: The Theories That Explain the Global Superiority of Greek Shipowners

Greek shipowners emerged from the two world wars with a substantially lower tonnage, a reduction of around 72% - 86%, or 1.32 m GRT of 428 ships in 1944. Despite these disasters, Greek-flagged shipping succeeded in being reborn. Is this a case of the phoenix birds of mythology?

Greek shipowners believe that their superiority comes from one of three sources:

• They are an alter-ego of Odysseus (Onassis);

• Their ships are phoenix birds, arising from the ashes of destruction;

• They have the spirit of a ghost.

The myth of the phoenix birds was adopted by Greeks, especially after the Second World War, and linked to the lend-lease of 107 Liberty Ships in 1946 (equal to 1.16 m dwt). These were sold to the Greek-flagged fleet (of 0.58m GRT, where 70% of the 88 ships was old) by the USA, on favorable terms.

Odysseus was the King of Ithaca9, nowadays Lefkas (meaning White10). Odysseus was brave, eloquent and shrewd. Greek shipowners, like Onassis, admired him in particular for his determination, cunning and resourcefulness. Odysseus was a historical person, who crossed Mediterranean, and also the Atlantic Ocean, according to recent research.

Most probably he wrote the Iliad and Odyssey as life memoirs, under the pseudonym “Homer”. Homer may mean “a man not seen” in Greek. No contemporary is recorded definitively to have seen Homer, and seven11 cities claim his birth. These places coincide with places Odysseus visited and stayed for some time, we believe. Odysseus demonstrated that in order to conquer a well-protected walled city like Troy, a rather intelligent strategy is required, namely the gift of “the wooden horse stratagem” (a horse containing soldiers).

Greek shipowners admire Odysseus because he was a powerful king, shipbuilder, shipowner and sailor. He faced Poseidon, the god of the sea, and blinded his son, Polyphemus, who was cleverer and better prepared than him.

The idea that Greek shipowners possess the spirit of a ghost was an illusion and has been abandoned in recent decades.

8. Part III: The Relationship between Greeks and the Sea

The Phoenicians were a Semitic people, living in Lebanon (in Tyre; and Sidon was their capital), with “Carthage12” as their famous colony. They were merchants, pirates, cunning people, with long experience, dealing with arts. They conducted their sea trade across the Mediterranean, including regular visits to Ithaca, as mentioned by Homer in the Odyssey (Goulielmos, 2009).

Certain Greeks believe that the Phoenicians invented the ancient monetary system. Others believe wrongly that Phoenicians invented the Greek alphabet. The Greeks knew how to write already at time of Odysseus, as mentioned by Homer in the Odyssey.

Sea trade was well established by the sixth to fourth centuries BC. Dominant cities in sea trade by 375 BC were Carthage, Syracuse, Corinth, Athens and Memphis (Egypt’s early capital south of Cairo). Two hundred years later they were Athens, Rhodes, Antioch and Alexandria. The main cargoes were grain, wine, oil and pottery from Athens, in exchange for metals from Carthage and Tuscany. By 500 BC, the Greeks established more than 100 colonies (Stopford, 2009: p. 10) in search of additional fertile land and sea trade.

The British, Portuguese, Spanish, Belgians, Dutch and French and others established hundreds of colonies in the 1700s, using military force in the first instance. Thereafter commercial ships took over the task of transporting manufactured products from the metropolitan center to the colonies, and raw materials from colonies to metropolitan factories. The process followed was first to build a naval fleet and then shipping followed. Thus, the dominant world naval powers, since 1700s, were also the great shipping powers, and about 11 of them maintain their position to the present day (Table 3). Establishing colonies is one convincing explanation for shipping superiority.

9. Part IV: Alexander the Great (356-323 BC)

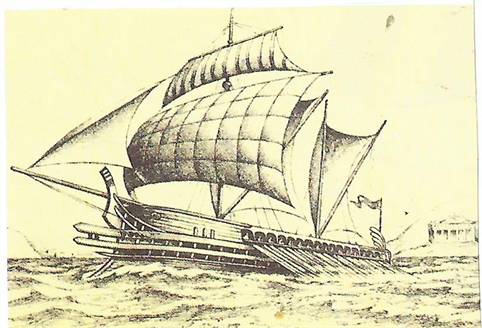

Greek shipowners consider ancient naval power (Picture 2) a precursor of their commercial shipping, and part of their shipping tradition as well (Koutsis, 2000). They are fond of talking about Alexander the Great, (King of Macedonia, 336-323 BC), who occupied Asia with 35,000 soldiers, and 160 ships. Alexander is noted for his speed in attacks against Persians13 and locations in Asia, including India. However, Alexander cannot supplant Odysseus in the hearts of Greek Shipowners.

Picture 2. An Athenian Trireme used by Alexander the Great. Source: author’s archive.

10. Part V: Greek Shipping during the Romans

When Rome ruled most of the known world, including Judaea where Jesus, Son of God, was born in 1 AD, and before, after 168 BC; they relied heavily on the traditional maritime people: the Greeks. In 328 AD Constantinople established as a capital city of the Eastern part of the Roman Empire, “Byzantium”, which was run by Greeks.

When the Greeks had the bad luck of having their country occupied for 377 years by the Turks (1453-1830), they were allowed to provide sea transport services, because the Turks were only familiar with mountainous professions. Only Greeks understood/carried-out shipping and sea commerce. Greek ships were protected by the Ottomans, and allowed to cross the Dardanelles freely. Following the 1774 convention (Russia-Turkey), the Greek ships were allowed to fly the flags of Russia, England, and Malta, as well those of the Ionian Islands. Greek ships competed the French ships.

As competition dictated, Greek ships flew the flag which was most suitable (protected). A flag policy started then, and is continued today. This means that a ship flies the flag which makes her competitive and effective. The love for the national flag is shown in many other different ways.

11. Part VI: Greek Shipping, 1830-1945

Greek shipowners worked from the UK, which was an international center, where cargoes for ships to places such as Argentina could be engaged, on the Baltic Exchange, which had been established in 1744 (Picture 3), The British had been lucky, as certain people tried to introduce coffee in the UK by establishing coffee shops, where Captains used to spend their off-board time and exchange information (Picture 4).

The big event during this period was the Great War, which started in 1914. Greece joined in 1917, after it reversed its decision on neutrality. Despite its late appearance, Greece lost 147 ships of 370,570 GRT (Ntounis, 1991).

Greek Shipowners moved away from sail and toward steam, but their transition took 65 years or so as shown in Table 2.

N D Lykiardopoulos (1866-1963), a shipowner from Cephalonia saw and admired a steamer in Lesbos in 1879. He established an office in Cardiff in 1875 and in London in 1901. He owned the Neda Shipping Co., which owned 3.58 m dwt in 2018, having the 23rd position among Greek shipowners.

The Greek state legislated that, in order for the taxes that had been levied on extra war profits to be returned to Greek shipowners, they had to buy or order ships, within a specified time, to the value of twice the tax rebate. The Prime Minister Venizelos believed that the Great War had put an end to the story of Greeks being shipowners. He saw that many shipowners invested in real estate. But both his assumptions were wrong (Figure 2).

As shown, the ship prices fell from a high level of £250,000 in 1918, to a low of £4500 in 1932. This shows the tragic reality of how important timing is in shipping (Goulielmos, 2021a).

![]()

Picture 3. Baltic Exchange—the old coffee house. Source: the Virginia & Baltic House (Huber, 2001).

![]()

Picture 4. A Coffee House. Source: Lloyd’s of London Press.

![]()

Table 2. Greek shipowners and the move to steam, 1850-1915.table_table_tableSource: author’s archive.

![]()

Figure 2. The 2nd hand ship prices, 1918-1939, paid by Greek Shipowners. Source: author’s archives. Not continuous years.

The main characteristic of the 1929-1935 period was the shipping depression due to the international crisis, which started during the last 3 months of 1929, mainly due to the collapse of Wall Street (Figure 3).

The crisis is indicated by two indices: trade and industrial production (Gratsos, 1938). K G Gratsos (1902-1981), a shipowner from Ithaca, argued that, in a cyclical industry like shipping, the ability to forecast is a prerequisite to success. He remarked that Greek shipowners are optimistic people, despite the huge tonnage laid up then. He used the following factors to predict shipping demand: 1) the prices of raw materials; 2) the USA’s industrial production; and 3) the purchasing power of European countries.

Twelve shipping nations figured in 1914 and in 1935 in top positions over 22 years (Table 3).

As shown, England was first in 1935, owning about 20 m GRT (32%), followed by USA, owning about 12 m (19%). Greece owned 1.7 m GRT (<3%), adding 890,000 GRT after 1914. In 1935, the world fleet increased to about 64 m GRT from about 45 m in 1914 a rise of 42%.

Greek shipping offices were established in the UK. The first was a Greek shipping representative, “Rethymnis and Kulukundis Ltd”, established in 1921. By 1939, Greeks established 16 shipping offices, managing 487 ships, in London, representing 210 other shipping offices, owned by 1500 co-shipowners. The UK was a boarding school for the Greeks, where Greeks alone, or in partnership with other Greeks or British, learned the shipping business the well-organized British way. In UK Greeks had a second-hand ship market, pioneering shipbuilding, ship finance and marine insurance.

Five main issues affected Greek-flagged shipping in the 1930s:

· Lack of adequate capital;

· Wrong intervention of the Greek state to make Greek shipowners to buy ships (as shown in Figure 2);

· Economies of scale;

· Bad relationships between capital and labor on board;

· Loss of the fleet’s competitive advantage.

![]()

Table 3. The 12 principal maritime countries (1914; 1935).

Source: author. Data from Lloyd’s Register. (*) 91% of the tons held by the 12 nations mentioned in 1935.

Greeks lacked the required capital to buy the more expensive steam ships, and there were no international banks at home. As a result, Greek shipowners turned to old, second-hand, ships, in need of intensive maintenance. These ships, called “tramps14”, were cheaper, but vulnerable to shipping crises. In 1935, only 18.5% of all Greek companies were public, meaning big. Greeks depended on the banks located abroad to finance, at least half of, their fleet (mainly in UK). In 1937, 62% of Greek tonnage was over 20 years old, while the 43% of the world fleet was under 15 years old.

Greeks had to mobilize the family savings, the savings of close relatives, as well those of local people, in a Greek system of co-ownership called in Greek “συμπλοιοκτησία”, meaning up to 200 partners. This mobilization of savings was essential for Greeks, who otherwise would not have been able to compete with UK shipowners who had millions of pounds at their disposal (a UK credit scheme with more than £100 m).

Finance, in shipping, counts for half the endeavor, and the other half is know-how. Finance is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for someone to become a shipowner.

Two flags of convenience emerged after 1939: Panama (1939) and Liberia (1949). 18% of the world fleet was using these two flags by 1969. This phenomenon characterizes the whole modern period in its various aspects. Statisticians started to register the national tonnage under foreign flags. Flags of convenience gave a strong competitive advantage to those used them, including Greeks. This partly ended in 1986/1987 with parallel registries established in EU.

Greek maritime labor policy was confused as to the nationality the crew on board Greek-flagged ships should have. At the beginning, Greeks argued that they own a big fleet and they have to recruit from a small population of around 8 million, which was (and is) true. The state allowed ships to have foreign crew at an increasing percentage. Initially this was around 20% or so, but as years went by it reached 35%. The mistake was to pay foreign crew as if it was Greek, something corrected in 1983.

Another mistake was to pay crew in US dollars rather than pounds. This was what the crews demanded, due to the frequent devaluations of pounds sterling, before oil was found in the North Sea. This changed again with the introduction of the Euro. Yet another mistake was to reduce the number of Greek officers on board by introducing the so-called “synthetic” complements. For shipowners this was positive, but 33% of the new shipowners were former Greek officers, and this move cut off the supply of new entrepreneurs. Thankfully, the captains were still Greek.

Greek efforts concentrated, from the beginning, on controlling labor costs, which they could control because they were paid within the nation, in the same way as administration and taxes (as shown by data). The productivity and skill of Greek crews, and especially of Greek Officers, contributed to this effort.

The increase in the number of ships flagged in Greece led to the employment of Greek crews from big cities, who, after 1917, were influenced then by Marxist theories. Crew problems were resolved by the unions. The state intervened using strict controls in shipping matters, such as crew complements, crew selection, detaining improperly manned ships15, obligatory employment of Greek seamen, numbers of specialist seamen, and so on.

As a consequence of the measures described above, Greek ships became expensive compared with the main competition.

To overcome these difficulties, Greek shipowners sought economies of scale, by following the common trend to buy/build larger ships (after 1931). But the larger ships had to find cargoes destined to large non-Greek and non-Mediterranean ports. As a result, Greeks had to manage their ships from UK offices/agencies and from elsewhere abroad, while they flew flags other than the Greek flag.

Between 1930 and 1935, Greek shipping restored its competitive advantage. This came mainly from low, or zero, taxation, lean shore offices or no shore office at all, leading to lower administration costs, and lower crew costs. Crew costs were kept down by…not paying overtime or leaves, spending little on crew food, high labor productivity at sea, and better ship maintenance. This is recognized as the Greek contribution of the sea labor to Greek-flagged shipping, serving willingly under austerity and difficult working and sleeping conditions. Liberties made the real change for Greek crews.

In 1934-1935, 6 ships built between 1907 and 1930 added to the Greek fleet.

An overall picture of the Greek-flagged shipping, between 1856 and 1945, is provided in Figure 4. As shown, the tonnage of the “Greek Steam Shipping” in 1915, and in 1945, after the end of the 2 global wars, was substantially reduced. The growth of the Greek shipping is impressive between 1919 and 1945, given also the 1929-1935 depression.

12. Part VII: The Greek Shipping and the 107 Phoenix Birds, 1946-1950

The ability to move internationally, which characterized Greek shipowners since ancient times, led them to establish offices in New York16 during the 2nd World War, fearing that UK would be involved in the war, as it was. The USA decided to spend more than $5.4 billion to build about 2700 ships of 10,500 dwt each, to achieve world’s liberty: the Liberty Ships. After the war, the USA decided to sell (“lend-lease”) them to its allies, on favorable terms, to compensate them for their war losses.

Greek shipowners17 grasped18 the opportunity and applied for at least 100

![]()

Figure 4. Tonnage under Greek Flag, 1856-1945 (not continuous years). Sources: Greek shipowners union, 1946; Bank of Greece; “Naftica Chronica” journal (2000); Hellenic Chamber of Shipping (1988); Data for Greek-flagged shipping registered in 1834.

liberty dry cargo ships and 7 liberty-tankers19, in August 1946. The Chairman of the NY Greek Shipowners Committee, a shipowner himself, Em. Kulukundis, in October 1945 wrote an article, strongly encouraging Greek shipowners to buy the Liberty Ships, and put them in the place of the ships they lost during the war. Capital was still needed, and especially in dollars, and this was provided in the form of loan guarantees from the Greek state.

By April 1947, Greeks had obtained the last ship they asked for, at a total price of $65 m (or $650,000 each), and they decided to fly the Panamanian flag, being dissatisfied by Greek flag, despite the help Greek Government provided in 1946. Greeks called the Liberty Ships blessed, and they were, and considered them a strong foundation on which they would rebuild their shipping industry. Can one forbid Greek shipowners to believe that the Liberty Ships were not their Phoenix birds?

After 1950, the Greek ships became expensive and hard, because of the high taxes imposed and the protectionist policies that other shipping nations adopted to promote their own self-sufficiency. Greece started to pay attention to its nautical education, an issue which will be always at the top of the agenda (Goulielmos, 1995).

However, Greek shipping rescued by the Korean War, in June 1950, even though the war was short. Wars cause an increase in demand, and any mistakes committed in building unrequired ships before, are suddenly justified. This coincided with recovery from a futile four yearly civil war that followed the four-year occupation by the Germans.

The new buildings of Onassis and Niarchos in 1949-1950 of “Olympic Torch” and “World Liberty” marked the end of this period.

![]()

Figure 5. Tonnage under Greek flag, Liberian and Panamenian, 1945; 1949-1950. Source: data from “Naftika Chronika” journal, 1979.

Figure 5 presents the situation in 1949-1950, compared with 1945, of the Greek-owned fleet under the Greek, Panamanian and Liberian flags.

As shown, in 1949 the Greek-owned fleet was 2.38 m GRT, distributed over 3 flags, of which the Greek flag accounted for about 55% and Panama almost 43%. In 1950, the Greek-owned fleet increased to 2.55 m GRT of which Greek flag accounted for about 50% and Panamanian 45%.

Onassis was the one to revolutionize the shipping business by using other people’s money laid-up in banks, and to achieve a faster growth. Onassis was honest with banks and he argued that he restored the bad reputation Greek shipowners had before him.

Traditional Greeks were afraid of the new-buildings, especially when market falls upon delivery, (as this has happened with the 2 VLCCs built by Colocotronis). Onassis was right from 1938 to two years before his death in 1975, and till end-1973, and the traditional Greeks were right, except that Onassis believed in crude oil demand, which “supported his decisions” for 35 years! New-buildings for traditional Greek shipowners was mere speculation, and grew slow by using past profits as and when the shipping cycle permitted.

Onassis (1900-1975) escaped from the disaster of the 2nd oil crisis in 1979 by…being dead, while he could not avoid his son’s death. Niarchos (1909-1996), however, being 9 years younger than Onassis and living 11 additional years than Onassis, he felt the tanker crisis in full.

13. Conclusion

Greeks attribute their superiority in international shipping to the fact that they have been sailors, merchants and shipowners since 10,000 BC. Their alter-ego is Odysseus. Moreover, they lived, since at least 2000 BC, in a beautiful country named Hellas, of which only 20% of its total area was suitable for farming. As a result, they had to turn to sea.

Greeks used their 1186 naval ships not only to conquer Troy in 2000 BC, and win the Battle of Salamis in 490 BC, but also to establish over 100 colonies and compete with the Phoenicians. Naval power, as used centuries later by certain European colonial nations, allowed Greeks to expand seaborne trade. As a result, tradition established them as merchants and shipowners. They then made themselves useful to both Romans (168 BC) and Ottomans (1453-1830) and gained certain freedoms, even though they were occupied. The Greek nautical tradition was maintained by certain Greek islands and ports during the 1700s.

British shipowners rested on their laurels and glorious past, while Greeks, from the start, understood that shipping is an internationally competitive industry, where past glory does not guarantee future, and the one with the lowest total cost is (and will be) the king. Greeks brought the wealth of the seas to their small country, helped by the labor they had on board because the national costs for crew, administration, and taxation could be kept lower.

Occasionally, Greek shipping asked governments for help, especially during severe shipping crises. At all times, it also asked for a well-educated, effective, efficient crew. On the other hand, the state saw Greek shipping as the goose that lays the golden eggs. The state called for help from its wealthy shipowners after national disasters like the Great War and the Second World War. But the Greek state is another David facing Goliath.

In 1932, the Greek Shipowners Union (established in 1916) argued that the Greek state was responsible for flagging-out20. The Greek state has sometimes had difficulties in understanding the Greek shipping industry21, and vice versa. But there was one thing everybody understood: war after war, Greek shipowners sacrificed their ships for freedom. Wealth and power without freedom counted for little among Greeks.

The first challenge in the history of the shipping industry was its transition from wind to steam for propulsion. The second was the transition from wood to iron for construction. The third, and most important, was the transition from iron to steel, again for construction. The fourth will be the smart ships using artificial intelligence as well a lighter, stronger and cheaper material in construction, something that is currently only in our dreams! Ships and economies of scale have walked hand in hand in the past, and the same will happen in the future.

Though we admire technological progress, steam deprived Greeks of one of their competitive advantages—efficient crews. Greeks first delayed the adoption of steam by over 60 years. They then had to employ expensive English engineers or well-paid Greek ones. Sailing ships were labor intensive, but Greeks were efficient sailors, unlike those in British and French ships coming from their colonies, and all repairs were made by Greek crews on board. Labor on board reduced over the centuries and crews paid the price of technology.

Studying the mentality of Greek shipowners over the years, Greeks, perhaps out of ignorance, but perhaps out of lack of funds, faced new technologies with great suspicion. Greek shipowners followed four principles: 1) to be protected from envy (national-international); 2) to be protected from competitors; 3) to keep secrets within their ship-owning family; 4) to hide their actions. We conclude that Odysseus had the personality, character and way of thinking of modern Greeks. Homer’s books are an excellent work of psychoanalysis of Greeks.

Traditional maritime powers failed to treat the phenomenon of flags of convenience in a systematic way. The EU witnessed this development in the 1980s, and Norway successfully solved the problem with the slogan: “Foreign crew on board, the ship as safe as it used to be”. Greek-flagged shipping lost another of its competitive advantages, the employment of non-Greek nationals on board.

Extensive study of Greek shipping shows that the Greeks never could protect themselves from shipping cycles.

If one studies shipping economic history carefully, it can be seen that the Greek state harmed22 shipping at times (after 1918) and benefited it at others. The Greek state provided no subsidies, as other nations did. Crews also harmed shipping with false illnesses and the like. However, Greeks promote three-party Greek shipping management, due to the 3Ss: Shipowners-Seafarers-State.

Greeks emerged first as single-ship-owners, where the shipowner stayed on board, and, due to lack of bank finance or state one like UK, there were hundreds of shareholders, all coming from the same island and having common kinship ties. Relatives were trusted and the captain was also the shipowner. Greek shipowners were greatly helped by all kinds of embargoes and wars at all times.

The Americans saved Greek-flagged shipping by selling to its owners the 107 liberties (1946-1947). It may be argued that this is just luck, and has nothing to do with: tradition, the many islands, the superior navy, the many colonies, and so on. The only thing one needs is to have unchartered ships when they are urgently required by charterers like Onassis, as the need for oil cannot wait.

14. Policy Recommendations

This historical analysis of Greek shipping since 10,000 BC fills a Greek chest with pride, but pride does not make businesses. The analysis confirms that a nation having sea in abundance and fertile land in scarcity, has to resort to trade and to the sea. This is especially true if one lives in an island. Thus, the whole history simply confirms that one can be skilled in ships and trade. Tradition has to be passed from father to son in order to be tomorrow. Professionals will always be needed, meaning that as long as charterers exist, shipowners will be around.

Various events crop up, including wars, embargos, the closure of canals, the collapse of stock exchanges, and natural disasters such as bad harvests. Shipowners are only responsible for having more ships than required. But ships pay the toll. While history may not be repeated, its lessons are valid: 1) Companies have to build up funds from profits to guard against a rainy day; 2) They have to control the cost of building or purchasing ships; 3) They have to take into account that they are in a volatile and unpredictable business world.

NOTES

1We are in favor of the foreign investments that pass over the relevant know-how to nationals, so that when investors return home, Greeks take it over and continue this production.

2Smith in chapter 3 dealt with the sea and river transport arguing that they cause markets to grow. Additionally, he wrote that Mediterranean Sea helped the creation of higher civilizations…

3Troy was an ancient Greek city near Scamander River in NW M. Asia besieged by Greeks. Its remains excavated in 1873-1881 by Schliemann at Hissarlik.

4In end 1900 the bigger, quadruple expansion engine introduced. The ship engine HP grew because the new boiler allowed greater temperatures, and economies of scale. The productive country in building ships was Italy followed by France. The quality of labor on board British and French ships was lower than certain others because they used people on board from colonies.

5He mentioned (p. 5) that the 1st Bill of Lading used in 236AD is shown in British Museum.

6The 24 islands, which mentioned by Homer, are: Corfu, Aegina, Tenedos, Naxos, Kythera, Delos, Lesbos, Skyros, Psara, Karpathos, Kastos (Tafioi), Asteris (Arkoudi), Kos, Lemnos, Echinades, Chios, Kasos, Samos, Samothrace, Cyprus (& Pafos), Kalymnos, Zante (& Marathonisi), Imbros & Sami (present Ithaca). Also, the following cities/areas/mountains/rivers/lakes, etc. are mentioned: Pontos, Athos, Karla (Volvis), Thrace, Axios, Strymon, Pindos, Olympos, Acarnania, Alfios, Karystos, Achelus (220 km) & Sarantaporos, etc.

7Inhabited first by peoples akin to Minoans of Crete (3000 BC) and then by Hellenes (2100 BC).

8Colchis was in Black Sea.

9King also of Doulichion (Cephalonia), Zakynthos (Zante) and Sami (present Ithaca) and part of Acarnania.

10Rigas Feraios in 1797 in Vienna designed a great map of Greece where places appeared in their ancient names. Lefkas had the name Lefkadia meaning white. Homer mentions Ithaca by the name Lefkadia.

11The Reader’s digest great encyclopedia wrote that Homer is a person of uncertain birthplace and date.

12Near Tunis; destroyed by Romans in 3 wars in 264-146 BC.

13In 1933 archaeologists discovered the ancient Persepolis, the capital of Persians in Shiraz and the palace burned down.

14Ships having no standard itinerary between ports. They go everywhere a charterer wishes.

15Onassis at this time flew Panama’s flag.

16Greek shipowners established unions in NY and in London: The Greek Shipping Cooperation Committee established in 1936 by a meeting in Fishmongers’ Hall.

![]()

17Onassis was not qualified as he was no member of the GSU; lost no ships during the war; fled no Greek flag! This caused the written strong protest of Onassis (Goulielmos, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c).

18Greek shipowners argued that the ships will be manned by Greek crews lived already in USA and Canada and will be trained by Greeks before signing-on. Lemos C M (1910-1995) took over this whole task.

19These were the first seeds in 1947 for more Greeks to enter the tanker sector. Greek shipowners helped by the fact that Norway forbidden the purchase of tankers due to lack of foreign exchange. Onassis, Niarchos, Livanos Sta. (1887-1963), Kulukundis Eman. Became, from what they were, golden!

20When a ship flows a flag that does not coincide with the nationality of her owner.

21This is the reason we believe for the State established in 1936 the “Hellenic Chamber of Shipping” as its consultant.

22The harm accomplished when the crew number on board Greek-flagged ships was excessive due to high unemployment at home; crew wages were higher than those paid by Italy, f. Yugoslavia, Turkey, UK and Poland; unreasonable claims for food forwarded; high compensations after an illness or accident; no-disciplined crew; disorder on board; lack of understanding from the authorities and a strict application of laws in favor of the crew; disputes had to resolve by the ministry; high taxation; expensive flag costs and high contributions for crew pensions; charterers did not prefer Greek-flagged ships and insurers did not insure them; lack of state interest and no protection in Russian ports.