Investigation of the Association between Type of Walking and Sense of Community (Case Study: ALAM AL-HUDA Pedestrian Zone) ()

1. Introduction

Nowadays various policies have been undertaken by the governments to create and enforce SOFC in society, in order to achieve healthier and happier society members. In New Urbanism (NU), which is a recent planning paradigm, creating a better quality of life is subject to building proper SOFC as well as establishing ties and interaction with neighbors [1] [2]. As a number of researchers have claimed, SOFC affects the quality of life, enhances happiness & satisfaction [3] [4] [5] and reflects a happy, flourished society with humanistic and emotional quality of collective life in the background [6]. An approach adopted by the urban planners in this regard is the precise designing of physical environments, which brings people out of their cul-de-sac and directs them toward public and semi-public spaces such as streets and parks [7]. Such places are considered as main cores centers of social interaction and community participation [8] as well as kernels of enhancing SOFC. In fact, the emergence of such a feeling in residents of urban zones would be extremely beneficial in solving the existing social problems. One of the topics of discussion in new urbanism (NU) supported by a large number of studies, is that enhancing the level of SOFC is simply achieved through distributing street patterns [9]. Therefore, creating and developing a pedestrian-friendly setting with easy access to the walking tracks as well as encouraging walking can be regarded as the factors promoting the level of SOFC in the neighborhoods [10]. Generally speaking, the factors encouraging walking behavior include:

・ Higher density [10] - [15].

・ Mixed land use [13] [16] [17] [18] [19].

・ Easy pedestrian access and walkability [10] [20] [21], improvement of cyclist conditions [10].

・ Improvement of cyclist cycling conditions [10].

Moreover, the goal and frequency of walking activities do affect SOFC as well [22]. The typology of the built environment can enhance the potential interaction via the effect of two variables, namely: the improvement of the stationery and mobility elements and encouraging static activities. A number of variables are recognized to facilitate stationary activities, including the provision of seats and sitting areas [21] [23] [24] [25], community gathering spots [26], greenery [25] [27] [28] using a fine hierarchy [29] [30], activity generators (e.g., food) [31] [32] [33]. According to the studies conducted in the field. Evidently, the consideration of walking issues in urban neighborhoods has been the mere concern of researchers rather than attending to urban pedestrian zones which are formed for social purposes. In this study, we have taken different dimensions of SOFC into consideration, seeking to find appropriate responses for the following questions addressing the topic of this research:

・ How do the aspects of walking differ from each other (with regard to the sense of community?

・ Can we claim that an urban pedestrian zone is capable of creating and enhancing SOFC in itself (neglecting the goals and frequency of walking activities occurred)?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sense of Community

First, confirm that you have the correct template for your paper size. This template has been tailored for output on the custom paper size (21 cm × 28.5 cm). The major element in projects which target life quality is the creation of “the sense of socialization” which is an outstanding component of social capital and one of the three organized social destinations asserted in the Modern Urbanization charter [34]. In other words, sense of duty, personal responsibility and commitment reflect an intertwined chain of beliefs and interests among individuals in a community [35]. The concept of “socialization”, in essence, describes sense of belonging to different community forms such as residential community [36], interest groups [37] and even virtual groups [38]. Thus, it counts for not only a prosperous society with enhancing personal capabilities and exciting cooperations in social life [6], but also it is considered as a compliment for individuals socializing. In this regard, the most crucial factor in socialization is the power of attachment and social bonds between the members of a group a community, on the other hand many scholars believe that such a feeling can play the role of a catalyst in facilitating participation and social development since it has the potential of engaging in different social attitudes and behaviors such as the civil forms of community participation as well as the various common/uncommon forms of political participation. In the conceptualized 4-D Model for the “sense of socialization” by Mac Millan & Chavez (1986) the components of “membership, influence, reinforcement & emotional connection” have been regarded as the vital constituents for the creation and expansion of this sense [39]. Within the framework of this model, membership refers to the sense of belonging to a group and being a part of it. It includes the various aspects of having similar boundaries, shared background knowledge or history, feeling of emotional safety as well as personal investment in social life. Influence entails a person’s perception of bilateral ties; mutual influence. It emphasizes that individuals need to have opportunities to attend in social activities and make their own contributions. Members of a community need to observe the influence of their collective decisions and social activities while they are aware of the fact that such deeds are influenced by the community itself. Thus, is regarded as mutual influence. The third element is reinforcement: integration and fulfillment of needs, which indicates the advantages that community members gain from their membership by referring to the favorable links between members and their community. It reflects the degree to which a particular community provides the conditions for its members to achieve both their personal and collective goals. And the 4th component, shared emotional connection, corresponds to individuals having commonly shared repertories, (e.g., important happening, history, dates) which can affect the quality of social ties within a community [39] [40] [41].

2.2. Sidewalks and Walking

Following the reduction of life quality in Europe especially in 1950s, the issues of human presence and walking in cities were noticed considerably by the urban planners to help revive welfare in urbanized areas by creating public spaces [42]. Sidewalks, paths and hallways are among this group of public territory structures. Walking is also regarded as the most basic and fundamental possibility for doing activities, observing places, having enthusiasm and dynamicity, exploring values and hidden attractions in urban atmosphere. Littman defines walkability as the condition of having the quality of walking such as being safe, comfortable and convenient [43] also it is necessary useful and interesting [44]. Consequently, Lund [45] and Kim [46] maintain that, if residents are provided with more properly designed, walkable areas in their local surrounding, then this would contribute to more chances of interaction with neighbors and other settlers. This would, in turn, create a shared positive sense among them. As a matter of fact, existence of urban sidewalks or walking paths is regarded as a suitable response to the human’s need for mobility and a wide range of activities in the socializing process happen in these areas including: shopping, eating out, waiting for a friend, etc. A specific feature of the sidewalks which makes them more appropriate for urban activities is that transportation of automobiles and motor vehicles in these spaces is either omitted totally or has been limited to night hours in a few cases. Enhancing the safety of pedestrians, allocating spaces to walking activities and enriching urban appearance are some of the main features of urban sidewalks. Watson et al. [47] quote Brambilla and Longo [48] who claim that walking paths have the very first position among urban spaces where pedestrians are fully dominant, since residents notwithstanding of their age and physical ability―can trust these spaces and feel the safety comfort, fitness and attraction in walking. In fact, these spaces can be regarded as destinations for coming to, staying and attending in urban life [49]. This could improve the potentials of interaction through optimizing the elements of mobility and encouraging constant activities. Thus, developing hall ways and walking paths plays an essential role in increasing resident’s interaction, public participation and sense of socialization.

2.3. The Link between Walking and SOFC

In recent years, various studies have concentrated on the creation and development of SOFC in different fields of science including urban planning, environmental psychology and urban design to conceptualize SOFC and its decisive factors to target social health and wellbeing. Some of these studies have deal with the issue of walking areas and the effect of SOFC from both quality and quantity-oriented prospective, some introducing hypotheses and theories in this regard. One of these most well-known is labeled as New Urbanism (NU). It maintains that user-finally walking areas facilitate the creation of SOFC and pedestrians develop a sense of belonging and shared feelings among them. They realize that members’ needs will be ideally met by their commitment for being together [39]. Therefore, new urbanism in theory refers to the direct and indirect links between the walking areas and SOFC as a device to expand a stronger society. Another claim repeatedly expressed by the researchers maintains that an aspect of SOFC, i.e., walkability, refers to a property of the physical environment which accommodates pedestrian activities by using human scale and high-quality street environment [50] [51] [52]. Such activities enhance the chance for interaction among pedestrians and, in turn, increase social integration [22] [53] [54] [55]. Lund (2002) compared traditional residential neighborhoods to modern suburban areas and confirmed that the quality of a walking area affects SOFC [45]. Moreover, Ben-Joseph (1997) indicated that people who tend to spend more time in the streets, are more likely to develop social interaction [56]. Similarly, Kim (2007) asserted that there exists a link between walking paths and social activities, introducing it as a facilitator for interactions [46]. Lund (2003) studied walking activities at neighborhood level and declared that there is an association between the frequency of walking within neighborhoods and unplanned interactions among residents which might contribute to the formation of social ties [55]. Lund (2003) further claims that by developing environmental perceptions which are conducive to walking, it would be possible to increase the opportunity for such unplanned encounters [55]. Wood et al. (2010) also maintain that although the ability of walking in the neighborhood might encourage the act of walking/but it only includes leisurely walking not fast walking or jogging. Thus, neighborhood walkability may not automatically contribute to enhancing SOFC since the type and goal of walking may play a decisive role in this process [22] they argue that different dimensions of walkability account for different outcomes. For instance, a certain factor that might reduce leisurely walking and SOFC may not meddle with transport walking or exercise walking. However, it is worth mentioning that over-crowded areas full of visitors and motor traffic are probable to reduce leisure walking and in turn decline the chance of forming local connections among pedestrians. A quality-oriented research regarding SOFC and walking areas was conducted by Eunhye Jung et al. who investigated two residential apartment complexes with similar conditions in Seoul, Korea. This case study included 212 participants and after the T-test and regression evaluation demographic factors are neutral on SOFC, a finding which was consistent with Lund (2002). In this study, social interactions were reported to be influential on SOFC, as previously asserted in [45] [57] [58]. Finally, it was proved that whenever planned environments for walking are designed to concentrate on walking capabilities, residents would be able to interact in their residential complex and this would enhance citizens’ SOFC [59]. Albert Tsai (2014) conducted a study on the residents from 19 residences in Beiteu region, Taipei. He concluded that installing public services and amenities close to residential areas can be more effective than offering various programs to enhance SOFC. The questionnaire used in the mentioned study analyzed the actual time of daily journey including transportation to work, shopping, sport, going to school, journey to bank, recreation, picking kids from school, going to the library, post office, clinics and participation in social activities, neglecting the frequency and type of transportation. Results indicated that if these activities occur while cycling or walking, residents assume that they will have more time to visit neighbors, thus SOFC is enhanced [33]. Wood et al. (2010) suggested that SOFC tends to increase in settings and environments where people are encouraged to walk slowly. This claim refers to lower levels of mix land use higher levels of commercial FAR (flour space to land area ratio). The results of this study announced that the presence of commercial targets in a neighborhood is an obstacle for social interactions among residents unless urban design is implemented to create pedestrian-friendly centers [22]. In yet another study conducted in the urban zone in PORT Australia, Wood et al. (2012) assessed some measures of SOFC and of walking and its goals. Also, objective measures including. Perception of the neighborhood was another category which embedded walking infrastructure, neighborhood aesthetics, traffic hazards and safety. The results confirmed that there is a relatively similar relationship between pedestrian behavior, objective measures of the neighborhood, and perceptive measures of the neighborhood with SOFC. Meanwhile, by analyzing the demographic variables it was concluded that the retired group displayed higher levels of SOFC whereas those who held university degrees of B.A or higher education had less SOFC compared to other groups. The length of stay also had a converse association with SOFC as was the case with walking infrastructure and neighborhood aesthetic factors. On the contrary, there existed a negative correlation between traffic hazards and risk of crimes and SOFC. Consequently, it was concluded that residential density is inversely associated with SOFC. From another point of view, the results revealed that walking for pleasure is less associated with SOFC as compared to walking for transport [60]. This finding was, however, controversial to the ones reported earlier [22] [45], but in line with Dutoit [61] regarding a residence in Australia.

3. Case Study

3.1. Rasht

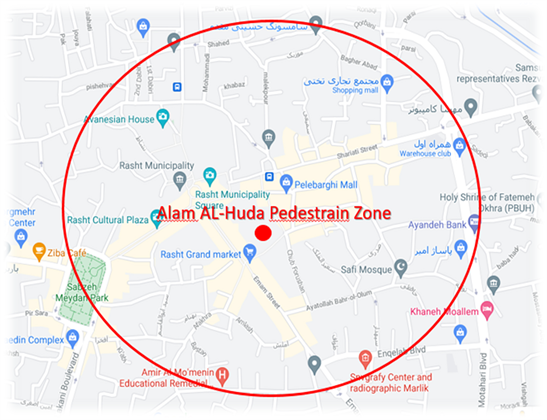

As it is shown in Map 1 Rasht (the capital city of Gilan Province) is the largest city on Iran’s Caspian Sea coast with a Mediterranean climate that its history goes back to the 13th when Rasht was a great transport and trade center which linked Iran to Russia and Europe, so it was known as the “Gate of Europe”. The history of the city goes back to the 13th century but its recent modern history dates back to the Safavid era (1501-1722) during which Rasht was a significant silk trade center with plentiful textile workshops. Rasht is growingly turning into an industrialized town like most of the Iranian large cities and province capitals. Rasht is known for its famous Municipality building and other modern heritages, located in a square called the Municipality (ALAM AL-HUDA).

3.2. ALAM AL-HUDA Pedestrian Zone

ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone is located in downtown Rasht, GILAN province. As shown in Map 2, it is similar to a plaza with a vast area surrounded by all the facilities and amenities required for walking and recreation, with no motor traffic and suitable for cycling and promenade. Exquisite landscaping and superb illumination techniques, large musical fountains, statues of local celebrities as well as urban elements depicting the cultural identity of native residents in addition to installed sitting equipment and facilities for relaxation are among the urban furniture seen in the area. This pedestrian zone attracts different people from various age groups and social orientation. As shown in Figure 1, it is surrounded by historical buildings and a combination of businesses and cultural-recreational centers including cafe, library, shopping center, cinema, local bazaars and a considerable number of vender stalls. An interesting point is people’s presence in the area at late night hours as well as their participation in numerous cultural ceremonies held on different religious, national occasions.

Map 1. Location of Rasht.

Map 2. Map of ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone.

![]()

Figure 1. ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone at night.

4. Methodology

4.1. Focus Group

Equations The present study investigates sense of community in individuals who enter ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone for 4 different goals in fact, the emphasis here is on probing SOFC in an urban pedestrian zone instead of neighborhood respondents were selected such that all the various groups of people present in the area are included, such as: pedestrians, shop keepers, vendors, clerks, etc.

4.2. Measures

The major factors involved here are recognized as the independent variable of “walking” and the dependent variable “sense of community” Questionnaire items designed to assess these variables include three types: demographic questions, items on type of walking and items assessing sense of community. The responses on these items were there scaled and categorized according to Likert scale, scaring from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Item no 20, in specific, concentrated on measuring the level of individual’s preference with regard to walking in ALAM AL-HUDA track rather than in other local routes. The demographic variables inquired here include gender, occupation, educational background, residence in RASHT and the distance between the pedestrian zone and respondent’s place of residence.

4.3. Different Types of Walking Activities

In this study walking activities are considered in the framework of 4 groups of participants who pursue these acts for different objectives:

・ Forced walking (to arrive at work place), also known as compulsory or work walking, includes those individuals, whose place of work and duty is located within the area of the walking trail and they are forced to walk through the lounge vendors, library and municipality clerks, shopkeepers and those who work in the buildings nearby belong to this group.

・ Recreation walking (wandering, promenade) which refers to those groups of users who come to the area just to enjoy their leisure time.

・ Exercise walking includes those individuals who use the pedestrian zone space to practice sports or go for jogging, running, cycling or exercising different sports. Mainly their goal is attached to health objectives.

・ Finally, transport walking which refers to those people pedestrians-who just pass through the area to arrive at their daily destinations and they do not tend to stop there.

4.4. Physio-Environmental Elements and Activities

This includes safety, participation, walking infrastructures, aesthetics factors; user interaction and urban form of the location were also assessed and evaluated in this study with regard to SOFC issues. Table 1 demonstrates each category.

4.5. SPSS

SPSS is short for Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, and it is used by various kinds of researchers for complex statistical data analysis. SPSS has easy access to data with different variable types. These variable data are easy to understand [62]. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is one of the statistical methods of many other statistical methods of SPSS. ANOVA in R is a mechanism facilitated by R programming to carry out the implementation of the statistical concept of ANOVA, i.e. this technique is used to answer the hypothesis while analyzing multiple groups of data. There are multiple statistical approaches; however, the ANOVA in R is applied when comparison needs to be done on more than two independent groups. Analysis of variance, a technique that allows the user to check if the mean of a particular metric across a various population is equal or not, through the formulation of the null and alternative hypothesis, with R programming providing effective functionalities to implement the concept through various functions and packages [63].

![]()

Table 1. Main questions/items on walking activities, SIC, physic-environmental factors.

4.6. Regression

Regression analysis is a powerful statistical method that allows writers to examine the relationship between two or more factors of interest. In regression analysis, those factors are called variables. While there are many types of regression analysis, at their core they all examine the influence of one or more independent variables on a dependent variable [64].

4.7. Data Analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS 16. Initially, the responses on the demographic questions Asserted in the questionnaire were evaluated then, the association between the dependent variable “walking” and the independent variable “SOFC” was determined using regression methods in this regard, the value of R was specified within the range of −1 < r < +1 to reflect the linear correlation coefficient and linear relationship between the variables next the statistical method of analyzing variance “ANOVA” was conducted in which observations and data on walking and SOFC were assessed to confirm the existence of a relationship. Multivariate analysis of variance and frequencies were also utilized to evaluate the simultaneous effect of several factors on the dependent variable.

5. Results

The results on demographic questions revealed that from among the overall population of 251 respondents who participated in the survey. “46.2%” were male and “53.8%” were female. The questions on occupation included 7 distinct groups of clerks, students, retired, professions, unemployed, freelance, others. Among these categories, the self-employed had the maximum “32.3%” of the total while the unemployed. Respondents were “21.9%”, clerks “17.1%”, students “14.7” others “8.0%” and the retired respondents were measured to form the minimum “2.8%” if the population. These statistics can indicate that the large percentage of the self-employed users is a sign that this group including shopkeepers and businessmen of the nearby in the area stores, use the pedestrian zone to get to work. Meanwhile, one can guess that the unemployed users, most probably, go to the pedestrian zone for passing time and enjoying their leisure; clerks use it to get to work and students are present in the area for recreation and possibly practicing sports. The statistics, moreover, maintain that the variety of users from different social, cultural and economic backgrounds attend in the pedestrian zone. Considering the educational status of the users, the results revealed that “37.5%” of the respondents had a university degree of B.A or B.S level. While a trivial difference, “35.1%” held M.A or M.S degrees. It was shown through the calculations that “9.2%” of the respondents had a PH. D whereas “12.4%” had a high school diploma and “5.6%” were undergraduate students and “0.4%” of the total respondents and only passed elementary school level education. These statics reflect elementary school level education. These statics reflect the presence of a large number of educated individuals in ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone.

5.1. Demographics

Two Questions addressed the duration and length of stay of respondents in Rasht and the distance from their residence. Respondents on the question dealing with the length of residence indicated that the highest percentage belonged to those residing in Rasht for 2 - 5 years “29.1%”, followed by 5 to 10 years of stay “23.5%”, less than 2 years “21.1%”, more than 20 years “18.7%” and 10 - 20 years “7.6%”. These statistics demonstrate that the level of user’s participation & presence in the pedestrian zone is not dependent on the duration of residence, reinforcing the hypothesis that sense of community is a decisive factor in people’s making decision on participating in urban pedestrian zones. Another question regarding demographic factors addressed in the questionnaire showed that the place of residence for “31.1%” of the respondents is located at “10 - 20” minutes’ walk from the pedestrian zone, while for “29.1%” of the total population it takes more than 30 minutes, for “27.1%” between 10 to 20 minutes and finally for “12.7%” less than 10minutes. As the statistics imply, those who live at the far these distances to the walking trail participated the most in the area. This indicates that sense of community and presence in a favorable setting with pleasant situation and desired facilities are factors affecting user’s priorities with regard to selecting a proper place for walking. The major questions in the questionnaire inspired by other sources are as follows Main questions/items on walking activities, SOFC, physic-environmental factors.

As was indicated earlier, the items were designed to address four types of walking to classify respondents based on the answers and to investigate which groups tend to participate more in the pedestrian zone. The remaining set of questions focus on specifying the role of physical and environmental variables of the trial on the level of sense of community.

The ultimate goal here is to determine which factors impose the most influence on SOFC in ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone.

5.2. Regression Model

Classification of the questionnaire (Table 2) items in addition to the standard deviation measures and percentage of scores in Likert scale are as follows: All the questions items are assigned to one of the above categories. Only item no. 20 is not a sub-category of either group since it deals with respondents. Preferences with regard to choosing ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone instead of the ones in their neighborhood statistics on this item revealed that, as we expected, “39.9%” of the respondents expressed their willingness to go for a walk in ALAM AL-HUDA pedestrian zone, irrespective of the distance to their place of residence. This feedback explains the possible effect of SOFC. As mentioned earlier in the methodology section, after the questions and responses were analyzed. The measurement of R was done to display the linear relationship between walking and SOFC.

![]()

Table 2. Classification of the questionnaire.

As indicated in Table 3, “R = 0.649” which is in the desired range of “−1 < r < +1”, reflecting the existence of a strong positive correlation between the two respective variables. In fact, whenever parameter of walking is enhanced, SOFC is expected to soar as well. On the other hand, the coefficient of determination (r2), which is the proportion of the variance in the independent variable that is predictable from the independent variable, assumes that the variations in the SOC are due to the effects of all the sub-constituents of walking. Table 3 illustrates the values for the coefficient of determination (r2) of this study as equal to “0.421” or “42%”. Chen et al. (1998), Hensler (2009) and Heir (2011) maintain that r2 can be interpreted in 3 different periods of “<19%” (weak), “<33%” (medium) and “>67%” (strong). Thus, the calculated r2 (42%) is situated in the range between medium and strong, indicating that walking predicts the outcome of independent variable (SOFC) to a large extent. In the next stage, we used ANOVA to further prove and establish the relationship between walking activities and SOFC. To do so, we searched the ANOVA table to see whether the regression model can predict the variations in the dependent variable significantly or not. The last column entitled “Sig” depicts the statistical significance of the regression model in which values less than 0.5 are considered as meaningfully significant. As suggested by the table (sig), the value for sig. in this research is calculated as 0.000, indicating that the applied model is an appropriate predictor for the variable of SOFC. Indeed, it implies that the model of regression is meaningful and significant and the assumption of linearity of the relationship between the predictor and the outcome. To obtain necessary data for predicting the dependent variable, then, the following table was analyzed. As can be inferred from sig. value both the constant and variable values for walking are significant at 0.000. the next column highlighted under the heading Beta displays the standardized regression coefficient which reflects the degree of influence by the predictor on the dependent variable. Here the value equals “0.649”, indicating that an increase in the value of standard deviation for walking by one point will lead to 64 percent enhancement in the value of standard deviation for sense of community. Since we investigate the multiple effects of several elements simultaneously, multi-variate analysis and frequency analysis were also conducted on the factors involved, including: transport walking, recreation walking, exercise walking, forced walking: as well as physics-environmental factors such as: Mix-use, sub-constructs, aesthetics, safety and people participation. The data were obtained from analyzing responses based on Likert scale ranging from score “1 to 5”. In order to further investigate the data precisely, they were split into smaller valid items. The results on what types or sub-categories of walking create the highest sense of community, are as follows:

1) Forced walking: enjoys the highest range of sense of community maintaining that those who work in the very atmosphere experience sense of community more than the others.

2) Recreation walking: the second highest sense of community with “0.4” variance compared to the first, still indicating that those clerks and complex staff of the walking trail who take their time to walk and promenade in the area for leisure have high sense of community as well.

3) Exercise walking: those individuals who inter the area with the goal of practicing sport activities or doing rapid exercises like running or jogging are placed in this group, having third position.

![]()

Table 4. Types or sub-categories of walking create the highest sense of community.

![]()

Table 5. The effects of 6 factors on the sense of community.

4) Transport walking: finally, pedestrians who just pass through the pedestrian zone and exist without stopping have the least, sense of community compared to other groups.

However, the results seem to be somehow controversial with regard to the frequency and number of participants attending in the walking trail as shown in Table 4.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the physical and environmental factors associated with urban walking trails affect user’s sense of community here, six factors namely: urban form, mix use, walking, infrastructure, aesthetics, safety and people participation were studied as the involved variables. The results confirmed that the factor of “safety” “33.9%” has the highest effect on S OF C. in ALAM AL-HUDA while “participation/presence “24.7%” takes the second position. The third factor affecting users’ sense of community proved to be aesthetics “20.7%” followed by infrastructure “20.3%” which includes structures such as concrete kerning, divisions for motor way and pedestrian walk, cycling and seating facilities as well as places for relaxation, with a trivial difference of “0.4%”. The last two factors are urban form and mix use with 19.1% and 17.9% respectively (Table 5).

6. Discussion and Conclusion

This study, like the studies carried out by Wood et al., assumed different objectives and frequencies for walking activities, investigating the effect of SOFC on each of these factors. In the present research, the purpose and frequency of walking were divided into four groups. In fact here, transport walking (as labeled by wood and other studies) was divided into two subcategories: forced walking, which refers to those who had to pass the pedestrian zone to get to work, and transport walking, which relates to individuals who use the pedestrian zone as a passage, perhaps with a momentary pause. The other two goals, as mentioned earlier, were related to those who walk for the purpose of getting exercise and contributing to their health, and those who walk to enjoy wandering and have recreation involving a longer pause in the pedestrian zone.

The results indicated high percentages of SOFC among individuals from the four groups so that even those who were labeled under the force walking group not only did they fail to express boredom with the daily and long-term presence in the area, but also almost displayed a high level of SOFC―only “4%” lower than those who attended the pedestrian zone for pleasure. In general the findings of this study are in line with Wood [22] and Lund [55] in that they all maintain that walking for pleasure is associated with a higher level of SOFC as compared to transport walking. It is worth mentioning, however, that transport walking as introduced in wood’s study was divided into two sub-categories in this study with the revealed maximum and minimum extremes of SOFC. This could be an indication of Wood’s finding in association with Dutoit [61] maintaining that transport walking has a higher SOFC as compared to leisure walking yet. The results express that SOFC in urban walking trails, including ALAM AL-HUDA, is affected by a series of physical environment which might mitigate the influence of walking goal. This needs further investigation in future research studies. However, from the six factors dealt with here, “safety” was realized to display the highest influence on users SOFC which is consistent with [65] clam with regard to the lack of motor traffic which enhances pedestrians’ safety and, in term [45], escalates SOFC, of residents within their neighborhood. The second most influential variable was recognized as “(individuals presence/participation)”. Wood asserts that in residential areas over-population and the presence of large numbers of residents strangers are negative factors reducing SOFC and social interactions. The categories titled “mix-use and urban form” imposed the least amount of SOFC. However this characteristic of mix-use or variety of usages from a specific land or property, is in agreement with [22] regarding its inverse association with SOFC. They claim that mix land use declines the opportunity for interaction among residents, thus, reducing interactive walking. In conclusion, it is recommended that in analyzing the various aspects of SOFC, the appropriate setting be charged from residential spaces to urban pedestrian zone and tracks since the number of citizens entering these urban facilities is significantly increasing nowadays, and by enhancing SOFC for pedestrian zones, it is just possible to direct it to the local communities, neighborhoods and residences.