1. Introduction

Background of the Study

Historically, corruption has been defined as a behaviour whereby a public officer abuses his or her position because of private interests (Dimant, 2013). On one hand, corruption involves state officers, that is, anyone who holds a position of authority over public resources in the name of the government. On the other hand, corruption also exists within private businesses in the form of bribery, swindling, and disloyal employees tampering with company accounts for private gain (Dimant & Schulte, 2016). But, with specific reference to kinship systems the world over, history of Western political thought highlights that the appearance of corruption dates back to the times of Greek philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, Polybius and Aristotle. Furthermore, archives from the Middle Kingdom Assyria refer to civil servants taking bribes, with senior officials and close relatives of the head of state implicated (Dimant, 2013; Marquette & Peiffer, 2015; Becker, Boeckh, Hainz, & Woessmann, 2016).

Similarly, it was in 1979 when Bill Clinton, being elected as Governor of Arkansas, appointed his wife Hillary to chair the Rural Health Advisory Committee. Then when in 1993, elected as President of the United States, he again appointed his wife to chair a Task Force on National Health Care Reform. In 2017, President Donald Trump appointed his son-in-law Jared Kushner, as a senior adviser to the president. He then announced on 29 March 2017 that his eldest daughter, Ivank, would also become an official White House employee (Ombanda, 2018).

In Liberia, Ellen Johnson was accused of nepotism back in 2012, when apparently 17 of her family members were working in the country’s government (Ombanda, 2018). In Botswana, the patronage network saw relatives and friends of politicians become leaders of other institutions such as the army, local government and key private sector businesses, coupled by favouritism in the award of contracts (Sebudubudu, 2014). For example, Dikgakgamatso Seretse, the minister of defence, security and justice had been alleged—and was later acquitted—to award public tenders to his family’s company. Seretse is not only the cousin of the president; both he and President Khama are related to Rose Seretse, the Director of the Directorate of Corruption and Economic Crime (Sebudubudu, 2014).

But, in the contemporary period, kinship is largely inconsequential outside the family. The emphasis is not only in favouring family members, but also in favouring friends, associates and other social categories that have developed with modern socialization. This is what Nyukorong (2014) rightly identified as the “Whom you know” factor. On this note, a study done Mjoli, Harry, and Chinyamurindi (2018) to explore factors that affect employability amongst a sample of final-year students at a South African university showed that social connections had become a major role player in the labour market. Participants argued that they were not experiencing the labour market the same way as the other students because they lacked social connections in the job market and hence remained unemployed after their graduations.

In Kenya, a senior manager at the Kenya Pipeline Company admitted that nepotism is deeply entrenched in the company. He confessed that all senior and middle level managers had recruited many of their relatives into various departments. The engineering manager, at the time, agreed that his daughter was employed in the company and he was not the only senior manager with relatives (Ombanda, 2018) employed in the same company. So, when kinship system is interpreted within the perspective of this present study, then the system is like a double-edged sword. While its existence creates the spirit of brotherhood and harmonious existence in the State, it also has an inclination towards corruption.

Statement of the Problem

Corruption has been highlighted as a major threat to social transformation. Scholars argue that the vast majority of African people remain impoverished while a few elites enjoy the proceeds of corruption. Moreover, corruption halts access to quality education, healthcare and housing for the majority of the African population as it skews the allocation and quality of public service delivery. By negatively impacting on the sustainability of the economy, it erodes human rights and dignity (Absalyamova, Timur, Khusnullova, & Mukhametgalieva, 2016) as a clique of people immensely benefits from public resources through nepotism, ethnic cronyism and clientelism. This means that dealing with the problem of corruption in Africa requires a rigorous study on how corruption interacts with the African kinship system. However, most of the studies done on corruption in Africa have not taken into consideration how African kinship system relates to corruption. This has resulted in a lacuna of literature in this area and a gap in the study and knowledge of the subject. Therefore, this present study bridges this lacuna of knowledge in the area of corruption and African kinship system.

Objective: To explore how African kinship system contributes to corruption in Kenya

This objective explored the specific manifestations of corrupt behaviours that are linked to the African culture, especially through kinship system.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study was informed by the Clashing Moral Values Theory. According to this theory, the causal chain starts with social values that directly influence the behaviour of individuals. In many societies, no clear distinction exists between one’s private and one’s public roles. Rose-Ackerman (1999) rightly opined that in such societies, gift giving is highly valued, and it seems natural to provide jobs and contracts to one’s friends and relations. In this theory, out of obligations to friends and families, public officials engage in corruption. This understanding is important because some scholars such as Collier (2000) believe that corruption is an importation from Europe into Africa, such that even if there is an element in the present African society that encourages corruption, we cannot rightly attribute it to African culture but see it as a European perversion of African culture. But, other scholars such as Rose-Ackerman (1978) rightly believe that with or without European influence, there are elements in African culture that encourage corruption.

Kinship refers to a culture’s system of recognized family roles and relationships which define the obligations, rights, and boundaries of interaction among the members of a particular community. Kinship can be achieved through genetic relationships, adoption and marriage or through socialization. Kinship systems range in size from a single, nuclear-family to tribal or intertribal relationships.

Africans are known all the world over for their sense of kinship. In fact, scholars have generally agreed that kinship has been one of the strongest forces in African life. Reflecting on African of kinship, Mbiti (1969) writes that kinship system is like a vast network stretching literally in every direction to embrace everybody in any given local group. This means that each individual is a brother in-law, uncle or aunt, or something else. Then, according to Achebe, “they said a man expects you to accept ‘kola’ from him for services rendered, and until you do, his mind is never at rest... a man to whom you do a favour will not understand if you say nothing, make no noise, just walk away. You may cause more trouble by refusing a bribe than by accepting it”.

Meanwhile, social scientists argue that cultures with stronger family ties are likely to experience public sector corruption than those with weaker family ties. Indeed, Orjuela (2014) cautioned that in societies where group identity is paramount, corrupt behaviours and actions in pursuit of personal again could extend to include the collective gain of a particular group or tribe. Thus, it is rightly argued that in African countries, there is the notion that peoples’ identification and relationship with the state and its institutions are much weaker than identification and relationship with the family, ethnic community and friends. Leaders are therefore expected to use their power to help their kith and kin.

A study conducted in South Africa argued that a man is not only married to his wife but to the wife’s entire family. The same applies to the woman. She is married not only to the husband but to the husband’s entire family. This means that the individual must fulfil all the obligations he or she has towards the family, even if it means being involved in corrupt practices. After all, it is this same relative or friend who will come to his or her aid in time of need. A much earlier study of public officials in Tanzania and Uganda found evidence that public officials who did not assist their friends and families risked ostracism.

But, in an indigenous African society where the language of corruption is alien would probably see nothing wrong with a civil servant helping his relatives, friends and in-laws when he and she is in a position to do so. But, it is exactly this indigenous African interpretation of kinship system that, this present study argues, has been imported into the contemporary society without taking cognizance of the differences between both the societies. Thus, those who are involved in corruption may apparently see nothing wrong with it because they think that it is part and parcel of the society. Consequently, what most Kenyans do is to wait patiently for their turn; when their man and woman would occupy the same position and favour them in the same proportion.

3. Methodology

Research design

In order to explore the views of the respondents on how African kinship system contributes to corruption in Kenya, a mixed methods research design was used with the premise that the use of quantitative and qualitative approaches, in combination, provides a better understanding of research problems than either approach alone (Creswell & Miller, 2000). The study was done in Kenya and targeted respondents from Machakos County. The county was chosen for this research due to its heterogeneous population. Because of the diverse characteristics of the target population, the researcher envisaged maximum variability within the primary data collected (Black, 2010). The county was also chosen based on the first-hand experience of nepotism and ethnic cronyism that the researcher had when processing land title deed in Machakos county.

Data collection and analysis

This study was conducted within two levels of populations: County employees; and the general members of the public randomly selected across the county. The justification for this nature of research was based on the researcher’s eagerness to compare and contrast the views of the county employees and those of the general public. Respondents from the county employees were interviewed by means of self-administered questionnaires while the general public were interviewed by means of In-depth Interview Schedules. The County employees were interviewed specifically on human resource management, financial management, asset management, services and authority management. The general public were interviewed based on services and envisaged employment opportunities within the County Public Service.

The initial sample size was 223 respondents but due to the outbreak of the Corona Virus in Kenya, most of the respondents had adopted “working from home” policy that was advocated for by the national government to reduce the spread of the virus in the country. This made it difficult to reach all the sampled 223 respondents. As a result, the researcher managed to reach 175 respondents. The response rate in this study was calculated by taking the number of successful responses and dividing it by the sample size, and multiplying the result by 100. In this case, the response rate was 175 ÷ 223 × 100 = 78.47%. According to Mugenda & Mugenda (2003), a response rate of above 70% is excellent. Therefore, the researcher considered a response rate of 78.47% as adequate for analysis and reporting.

This study adopted “non-probability sampling” and probability sampling designs. Non-probability sampling is the sampling procedure which does not afford any basis for estimating the probability of each item in the population being included in the sample. In this sampling design, items in the sample are selected deliberately by the researcher (Kothari, 2011). In this present study, the researcher justified the choice of a non-probability sampling design based on the premise that the county employees were deemed to have vital information for this study.

The study again employed probability sampling design which accorded all the county employees based at the county headquarters the possibility of taking part in the study. Simple random sampling was used to sample respondents. In this case, the list of all the employees was obtained from the human resource offices of the various departments and a total tally of the employees were calculated. After the list of the employees was constructed, the researcher fed the data of names into the computer Excel software and with the fx = RANDBETWEEN function, drew a representative sample of the employees. Finally, the researcher contacted each of those selected to obtain the information needed. Failing to contact all individuals in the sample can be a problem, and the representativeness of the sample can be lost. In order to mitigate against this failure, the researcher worked closely with the human resource personnel and the county secretary to easily navigate within the county without any restrictions.

The research instruments had been developed following the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Handbook on Tools for Assessing Corruption and Integrity in Institutions and adapted to the present context of Kenya. The handbook guides the user to identify and select integrity failures and vulnerabilities for which interventions should be considered. A pre-survey instrument was administered to 20 randomly sampled respondents in Machakos County to test the practicality, validity and reliability of the instruments. Sudman (1983) hypothesizes that a pilot trial of 20 to 50 cases is usually sufficient to uncover major defects in a questionnaire. The respondents in the pilot study were randomly sampled and were interviewed by means of a semi-structured interview schedule. The sampled respondents for the pilot study did not participate in the main study. The outcome of the pilot study was used to improve data collection instruments. It is important to note that the results of the pilot study have not been included as part of the final data results in this study.

4. Results

Demographic data of the respondents

Ethnic affiliation of the respondents

The intervening variable of ethnic affiliation was important in this study because Public Service Commission’s (2016) Policy Statement (PSC) stresses that every public service institution shall ensure fair and equitable representation of the diverse Kenyan ethnic communities. PSC (2016) envisages that all the Kenyan ethnic groups contribute positively to the economic, political, social and cultural development of the country. Moreover, the County Public Service Board is bound by the laws of the Republic of Kenya to ensure that at least thirty (30) percent of the vacant posts at entry level are filled by candidates who are not from the dominant ethnic community in the county and ensure open and transparent recruitment of public servants.

According to the research findings, Machakos County has twenty-two (22) identifiable ethnic communities, with Akamba constituting the majority of the total population. The remaining ethnic communities are the Agikuyu, Ameru, Abagusii, Abaluhya, Luo, Kalenjin, Aembu, Taita, Mbeere, Maasai, Mijikenda, Kenyan Asians, Somali, Teso, Borana, Nubi, Pokomo, Samburu, Tharaka, Gabbra, and the Abakuria. In terms of the county employees, the research found out that there is ethnic imbalance in the county public service. Majority of the respondents (73%), in the county public service, were from the dominant Akamba ethnic community, followed by the Agikuyu (16%), Meru (7%) and Kisii (4%). This finding is supported, with an insignificant variation, by the findings from the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (2016) that Machakos County has 79.0% of a single ethnic group in the county’s public service hence contravening the County Government Act.

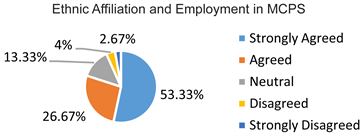

The variable of ethnic affiliation was again found to be a significant moderator between African kinship system and forms of corruption in Machakos County. When respondents were asked whether ethnic affiliation was a factor in employment in Machakos County Public Service (MCPS), 53.33% of the respondents strongly agreed, and 26.67% agreed, 13.33% remained neutral, 4% disagreed, while 2.67% strongly disagreed as shown in the chart below.

This finding points to a stronger in-group identity in Machakos County. This stronger group identity easily leads to nepotism in the public sector due to in-group favouritism (Dincer, 2008). This finding is further confirmed by Orjuela (2014) that in societies where group identity is paramount, corrupt behaviours and actions in pursuit of personal again could extend to include the collective gain of a particular group or tribe.

Gender of the respondents

![]()

The researcher sought to estimate if gender is also a significant moderator between the independent variable and the dependent variable. According to the research findings, 64% of respondents were male while 36% were female. According to Wadesango, Rembe and Chabaya (2011), many Africa states continue to have major inequalities in gender mainstreaming in all levels of the economy. However, with specific reference to the objective of this study, the respondents were asked to indicate whether corruption in Machakos County could be linked to gender inequality. Results showed that gender is not a significant moderator in corruption in Machakos County. Only 9% of the female respondents argued that there is gender favouritism in Machakos county public service; and 20% of the male respondents argued that gender influences corruption in Machakos County Public Service. This finding contradicts an earlier finding by Paweenawat (2018) which investigated the relationship between the share of women in parliament and the level of corruption in Asian countries during the period of 1997-2015 and found out that a larger number of women in parliament is associated with a lower level of corruption.

How African kinship system contributes to corruption

Nepotism

Nepotism is a situation where, for instance, civil servants single out individuals to favour them, not based on qualification or merit but on a kinship bond. According to the respondents, nepotism exists in Machakos County. The study found out that public resources have been used to benefit families of public officials. An analysis of the variables of gender and ethnic affiliation showed no significant variation in the responses. The following are some of the reported verbatim.

“County officials use county vehicles to benefit their families”.

“County resources have been allocated to specific families. For example, there are families whose children always benefit from CDF scholarships and those children are having family ties with some county officials”.

“There are county tenders that we know have been given to companies run by county officials and their relatives”.

Table 1 below shows the cumulative number of responses on the existence of nepotism in Machakos County.

As can be seen in Table 1 below, 71.4% of the respondents argued that indeed nepotism is a phenomenon in Machakos County Public Service, as opposed to 28.6% of the respondents who refrained from giving their opinion. This study therefore asserts that nepotism exists in Machakos County Public Service.

Moreover, the researcher sought to engage the respondents how nepotism reveals itself in Machakos County Public Service. The following tables present the analysis of the responses.

From Table 2 below, it is worth noting that those respondents who denied that county employees are being hired on the basis of their connections with county officials were senior employees of the county. This finding sharply contrasts the responses of the general public and lower cadre employees like subordinate staff who argued that the “whom you know factor” is operative in the county, although nobody wants to talk about it. The research further investigated the extent to which employees are promoted because of their connections

![]()

Table 1. Nepotism in Machakos county public service (n = 175).

![]()

Table 2. County employees are hired because of their connections with county officials (n = 175).

with county officials. Some of the respondents declined from expressing their views concerning this particular question. Moreover, through in depth probe, the researcher sought to specifically explore whether particular respondents had been promoted and or denied promotion because of having or not having links with senior county officials. The respondents said that promotions based on kinship links happen in the county public service. The results are tabulated in Table 3 below.

As evidenced from Table 3 below, this study argues that employees in Machakos County Public Service are being promoted because of their connections with county officials. This was attested to by 52.6% of the respondents.

The research further explored the possibility that the county financial inflows and services, among them the use of county assets such as vehicles and access to basic county services, are being influenced by kinship linkages. As per the tabulation of the results, 70% of the respondents argued that the speed with which one accesses services depends on whether the service seeker has any linkages with the service provider.

These findings have been confirmed by literature whereby the Kenya Civil Appeal 416 of 2019 documents that on 29th July, 2019 the then Governor of Kiambu County and 12 others were charged in Anti-Corruption Case No. 22 of 2019. The first count against the governor was conflict of interest in which county contracts were awarded to companies being run by family members linked to the governor. Similarly, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) approved the arrest and prosecution of Migori County Governor alongside his four children following an investigation by the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC). The investigations were in respect of Sh73.4 million being sums indirectly received by the Governor through his children who received multiple payments from companies trading with Migori County Government between 2013/2014 Financial Year and 2016/2017 (The Standard Newspaper, 25th August, 2020). Similarly, a Malindi Member of Parliament, as of August, 2020, was wanted by detectives in connection with the theft of Sh20 million from the National Government Constituency Development Fund (NG-CDF). According to the DPP, most of the funds that were allegedly stolen were wired back into the legislator’s personal accounts and those of her close relatives (The Standard Newspaper, 28th August, 2020).

Clientelism

![]()

Table 3. Employees are promoted because of their connections with county officials (n = 175).

Clientelism is a system where an influential decision-maker promises protection or assistance to a social group (clientele) in exchange for support. Connections of this type disturb the proper distribution of political and economic goods and services (Popczyk, 2017), hence are judged as acts of corruption. In its conception, clientelism incorporates certain friendship ties that are not necessarily familial but a group of friends to a decision-maker or a political leader works closely with the leader in exchange for goods and services.

According to the respondents in this study, the county tenders are allocated through skewed tendering processes and most of the time, the tenders are allocated to the friends of senior county officials. The respondents further argued that the process of disposal of county goods reflects the existence of clientelism. Below are some of the selected verbatim.

“County vehicles have been used to ferry goods belonging to the personal friends of officials”.

“County resources have been disposed at lower prices to friends of public officials”.

“There is a group of people who control the political class. They offer support to political candidates and once these candidates are elected, they are rewarded by being offered key county jobs”.

Table 4 below shows the cumulative number of responses on the existence of clientelism in Machakos County Public Service. From Table 4 below, it can be noted that 65 respondents disagreed that clientelism exists in Machakos County. It is noteworthy to note that majority of the 65 respondents who disagreed were employees of the county.

This finding is supported by literature with Van de Walle (2009) arguing that in the post-colonial African states such as Kenya, clientelistic resources served the purposes of cross-ethnic elite accommodation, in which the presidency sought to build a national elite coalition on behalf of the ruler, by including key elites from different regions, ethnic groups, and clans in the presidential coalition. The ethnic elites, brought into the presidential fold, were expected to play a kind of “brokerage” role between specific communities and the regime: the nomination by the president propelled them to a visible leadership position, in exchange for which they were supposed to ensure their groups support for the regime.

On public procurement, EACC (2015, 2016) conducted a study evaluating corrupt practices in public procurement in Kenya and found out that conflict of

![]()

Table 4. Clientelism in Machakos county public service (n = 175).

interest is rampant in public procurement. A total of 267 suppliers confessed to know firms either owned directly or through proxy by public officers. These firms would submit bids to do business with the government and win. The public officers owning these firms range from clerks, senior civil servants, procurement officers themselves to cabinet secretaries and their friends.

Ethnic Cronyism

Cronyism means mutual support exercised by people belonging to the same reference group in order to reach social and economic positions. This present study came to a grounded theory of ethnic cronyism after a thematic analysis of responses. Ethnic cronyism has been used in this study to refer to mutual favouritism exercised by people belonging to the same ethnic community. As already been shown above, ethnic affiliation is a major moderating factor in Machakos County Public Service. The respondents attested to the existence of ethnic cronyism particularly in the recruitment and promotion of employees, disposal of county assets, awarding of county tenders and financial management. Majority of the respondents (73%) argued that being of the same ethnic group as the top county officials determines ones’ fate in the county public service, i.e., employees get promotions majorly based on ethnic affiliation. According to one of the respondents, “if you promote more people from your ethnic community, your ability to influence county operations increases”. On the disposal of county assets and awarding of tenders, a respondent said: “it is safer to deal with a supplier who is of the same ethnic community as the procurement officers because they will be able to understand and cover each other in case the corrupt deal comes to light”.

The above views were supported by the argument of National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) (2016) that counties tend to recruit and promote employees from a single ethnic community (dominant) due to fear of the unknown. The unknown, in this scenario, may mean the fear of an employee from a minority ethnic community becoming a whistle-blower in the event of a corrupt practice by the dominant group in the county. Moreover, a study done by NCIC (2016) to assess the presence of or absence of ethnic diversity in the counties’ public service boards in Kenya revealed that new appointments made since the counties were established (2013 to date) have contravened the law. Only 15 counties (31.9%) have adhered to section 65 of the Constitution of Kenya (2010) by giving more than 30% of the vacancies to members of the minority ethnic groups in their counties. In fact, 68.1% of the counties have hired more than 70 percent of their staff from one ethnic group. The NCIC study also found out that County Executive Committees in 18 counties were mono-ethnic while 22 County Public Service Boards are made up of only one ethnic group. Furthermore, only 13 County Assemblies (27.6%) have recruited at least thirty percent of their employees from the non-dominant ethnic group while 34 County Assemblies have employed more than 70% from one dominant ethnic group in the County. Two County Assemblies i.e., Kirinyaga and Nandi, have recruited only one ethnic group in the entire assembly workforce. These findings rightly resonate with the caution of Orjuela (2014) that in societies where group identity is paramount, corrupt behaviours and actions in pursuit of personal again could extend to include the collective gain of a particular group or tribe.

Summary of key research findings

This present study has explored the interconnection between culture and corruption in Africa. It has particularly focused on the African Kinship System and the ways through which it positively contributes to corruption in Kenya. The research found out that through nepotism, clientelism and ethnic cronyism, African kinship system has a positive link to corruption in Kenya. Through nepotism, public resources are used to the benefit of public officials and their families. Through clientelism, public resources are used for the benefit of public officials and their friends and other social connections. Through ethnic cronyism, public resources have been used for the benefit of particular ethnic communities in Kenya.

5. Discussion

Having shown how African kinship system contributes to corruption, this study argues that Machakos county, among other counties in Kenya, has contravened Article 232 (1i) (ii) of the Constitution which provides for equal opportunities in appointment at all levels of the public service of the members of all ethnic groups in Kenya. Corruption has negatively impacted on the sustainability of the economy, corruption erodes human rights and dignity (Absalyamova, Timur, Khusnullova, & Mukhametgalieva, 2016).

So, how can an effective social transformation be achieved amidst persistent corruption in Kenya? Gyekye (1997) rightly observes that fighting corruption requires us to carry out moral revolution by making substantive moral changes in the society. This is a type of formation whose major goal is to cultivate inner motivations in people to develop a tendency to do what is right. It is fundamentally the formation of conscience. This paper opts for the role of religious movements in conscience formation.

According to Heidt (2010), religion is a powerful influence on human behaviour. The teachings of various religious traditions greatly influence how people act towards others. Chen & Liu (2009) claimed that religiosity is considered to be the most important and stable social force in shaping an individual’s life. Teymoori, Heydari, & Nasiri (2014) reported that religion is a social institution that dramatically influences individuals’ behaviours and daily actions as well as their social and political orientation. According to Duriez & Soenens (2006), in a religious community whose teachings include principled moral reasoning with schemas such as fairness, tolerance, common good, and rational choice, members are likely to show increased preference for this kind of moral reasoning. In contrast, in a community whose teachings do not include principled moral reasoning, members are likely to exhibit decreased preference for this kind of reasoning (Miltiadis & Ioannis, 2017).

Within the African context, religion permeates all aspects of life (Mbiti, 1969). In African life, the individual is immersed in religious participation that starts before birth and continues after death. For the African, to live is to be caught up in a religious drama as the idea of the sacred pervades people’s lives (Mbiti, 1969). Both the universe and practically all human activities in it, are seen and experienced from a religious perspective (Obaji & Ignatius, 2015) because African cultures are fundamentally sacral (Kirwen, 2008).

Whilst the African religious heritage remains a potent force that influences the values, identity and outlook of Africans, Christianity and Islam have also become major sources of influence in Africa. Christianity has been in existence in Africa for more than two thousand years and its enormous influence is undeniable. Evidence of such an influence can be seen in, for example, the number of Christian churches, and Christian institutional establishments in many African countries (Metuh, 2002). In turn, Islam has also been in Africa for a long period of time that has led Mbiti (1969) to comment that these two religions can both claim to have become indigenous in Africa.

Moreover, African political elite has often resorted to religion in their intense competition for the resources of political power. Religion is used in political campaigns as an instrument of competition (Obaji & Ignatius, 2015). The contemporary African cities present a scenario where more private buildings are being converted into prayer houses, and stadia are being used for religious crusades, streets within towns and villages, as well as highways often blocked by surging and enthusiastic worshippers who flock to crusades and religious conventions. Within this religious boom, the number of bishops, pastors, evangelists, faith healers, prophets, sheikhs, imams and gurus is increasing (Nwankwo, 2015). But, if religion is so much engrained in the African public sphere, how then can the remarkable rise in instances of corruption in so many African countries be explained? Could it be that the teachings of the dominant religious movements in Africa do not include principle moral reasoning?

Although religion is flourishing in Africa, many sub-Saharan African countries are corrupt and among the world’s poorest nations (Obaji & Ignatius, 2015). Many of the men and women who flock the churches on weekends and fill the mosques on Fridays are at one time or the other in such fraudulent activities as tax evasion, issuing and obtaining fake receipts, importing fake drugs, and bribery. All these practices are so commonplace and so widespread that many young persons are today unable to distinguish between good and evil or between right and wrong. Does it mean that religion is no longer a source of moral inspiration in Africa and in Kenya, in particular?

This paper contents that the missing link in religious practice in Africa is the formation of conscience. With specific reference to Christianity, Hauerwas (1985) rightly opines that the Church should provide political services, the most important of which is the development of people of virtue. But, for Hauerwas (1985), moral formation is not only about character, but also about the heart, i.e., conscience. This kind of moral formation, according to Hauerwas (1981), has a communitarian dimension. Christians are historical beings and part of a community shaped by its traditions and narratives from which they derive their identity. Moral formation, in this perspective, basically consists in a communitarian character formation. Christians are called to embody the story of Israel and Jesus as carried by their community and practice Christian virtues through the habits that form and are formed in worship, governance and morality. This involves the particular Christian narratives that elicits moral formation, active membership in the community and the correlative communal identity.

A mere virtue education would only direct attention to the particularist aspects of identity, community’s authority, virtues and the accountability to community without really disposing the individual to doing what is right. Moral formation is more like having the necessary knowledge and skills to follow communities’ values. But, conscience formation necessitates sound moral discernment and responsible decision-making. Conscience formation appeals to the responsibility of the individual in a moral life. As Connors and McCormick (1998: 146) rightly affirm,

Still knowing the truth, even loving the truth, is not the same as “doing the truth”. If conscience is our capacity to discern and respond to the moral “tug”, then persons with a highly developed conscience will always need to be persons of virtue. They will need to be persons who can act upon their knowledge and affections, who can make and sustain commitments, who can transform their judgments and desires into decisions and, ultimately, into behaviour.

In other words, knowing the truth that African kinship system has particular elements that promote corruption in Kenya, and knowing that corruption harms the common good of Kenyans, does not necessarily lead to shunning corruption. Moreover, knowing the legal anti-corruption policies in Kenya does not necessarily mean that a person will not engage in corruption. These anti-corruption policies are moral dictates, but still corruption is persistent in Kenya. For individual Kenyans to act upon the anti-corruption policies and other moral frameworks put in place to curb corruption in Kenya, a mature conscience formation is here advocated for. Persons with mature conscience will choose to perform right actions. They will act upon the moral dictates of the community (Connors & McCormic, 1998: 146).

Conscience formation implies that the Church should go beyond mere preaching by more intentionally connecting its teachings with the public life of its members hence stimulating their conscience. But, how can this be achieved? This paper opts for the integration of social activism as a pastoral activity of the Church. To neglect social activism in favour of sacramental and devotional life is to ignore the Christian prophetic duty. The Church’s weekly meetings need to be integrated with a deep social analysis of the social, political and economic issues affecting the community, particularly corruption. Holland and Henriot (1980) rightly observe that social analysis that entails—See, —Judge and —Act process is simply an extension of the principle of discernment, moving from the personal realm to the social realm. The social analysis offers individuals abilities to obtain a more complete picture of a social situation by exploring its structural and historical relations. Social analysis will enable congregants to discern all the factors involved in a social problem so that right responses may be chosen.

Empowered by religious narratives, both scriptural and social, social activism envisaged in this strategy will allow congregants to participate in organised peaceful demonstrations to protest the ravaging corruption in Kenya. Religious narratives imply certain stories of Christian heroes who have fought and laid down their lives for political change and common good across the globe. The Church leadership should document these narratives to retell histories of heroic action and momentous victories, encouraging contemporary congregants to repeat the deeds of such past heroes. In addition to shaping group identity, such narratives can help motivate deliberate actions in pursuit of change because they appeal to the inner conscience of individuals.

The narrative of Dedan Kimathi whom, after eight days of trial, Chief Justice Kenneth Kennedy O’Connor sentenced to be hanged. Early on the morning of 18 February 1957, Dedan Kimathi was hanged to death and buried in the grounds of Kamiti prison. For many in Kenya, however, Kimathi conjured other historical comparisons. Ochieng’ (1992: 134) argued that Kimathi had been “elevated to the ranks of Mao, Lenin and Guevera”. Mazrui (1963: 28) placed Kimathi among the top candidates in Kenyan history to be anointed a national martyr, akin to other global anticolonial heroes the likes of Gandhi. When Nelson Mandela visited Kenya in 1990, he invoked Kimathi’s name in a speech at Kasarani Stadium: “In my 27 years of imprisonment, I always saw the image of fighters such as Kimathi as candles in my long and hard war against injustice” (As quoted in Shamsul Alam, 2007: 41). Other notable Kenyan martyrs whose narratives would provide an insentive for moral action against divisive corruption include Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Ronald Ngala, Tom Mboya, Masinde Muliro, and Achieng Oneko, among others.

6. Conclusion

In summary, this research explored the various ways through which African kinship system contributes to corruption in Kenya. By means of mixed research design and respondents sampled from Machakos County, Kenya, this paper has highlighted that persistent corruption in Kenya is linked to the indigenous worldview of the Africans that continues to operate within the kinship system. This worldview has seen corruption being perpetuated in Kenya through acts of nepotism, ethnic cronyism and clientelism. The paper has also highlighted that this persistent corruption threatens sustainable development in Kenya and halts the process of social transformation in Kenya. However, the paper has identified the role of conscience formation by religious communities in Kenya as a way of changing peoples’ worldview so as to perpetuate the common good of all Kenyans.