Determinants of the Access to Electricity: The Case of West African Power Pool Countries ()

1. Introduction

Despite the existence of many sources of primary energy in Africa, this continent seems lagged behind in respect with access to electricity. As a reminder, the access rate defines the rate of the population (household) with electricity connection. In 2008, the International Monetary Fund pointed out that the biggest deficit in Sub Saharan Africa in terms of infrastructure was observable in the power sector (Fond Monétaire International, 2008: p 84) [1]. Regarding the other regions of the world, Africa’s lag is related to generation capacity, the quality of the grid, per capita consumption and the access rate (Kojima and Trimble, 2016) [2]. Indeed, in 2016, about 600 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa did not have access to electricity.

The access to electricity is all the more an important question that in developing countries, rural electrification may be benefit for educational result of children, security, income potentialities of active population, reduction of air pollution for household using biomass and employment opportunities (Dinkelman, 2011 [3]; Banerjee et al. 2015: p 10 [4] ). The importance of electricity in the literature is testified by many articles such as the one of Trotter et al. (2017) [5] reviewing around 306 articles for describing the interest of researcher for this matter.

Although the access to electricity is a major concern of developing countries, there is not plethora of empirical studies. The existing literature about sub-Saharan countries is not typical of West African countries and does not take into account supra-national influences. For instance, the article of OONA (2010) [6] does not include the institutional framework and only focus on rural area. In the same vein, the income per capita and institutional framework are not taken into account by the articles of Vaona & Magnani (2016) [7] and Mwizerwa & Bikorimana (2018) [8].

Most specifically, the importance of electricity encouraged many supra-national (regional) initiatives. In West Africa, a regional regulation agency have been created in 2008 preceded by the creation of the West African Power Pool (WAPP1) in 1999 by the decision A/DEC.5/12/99 of December 10th, 1999 and in July 6th, 2006 by the decision A/DEC.18/01/06 concerning its organization and functioning. This initiative supposes a new [regional] market working in good articulation with existing national markets, but with specific rules concerning “Regional transmission Network” (AF-MERCADOS EMI, 2011) [9]. Although, the structure of the electricity market is not the same in all the countries, the WAPP is organized in such a way as to pool potentialities in terms of resources, develop and reinforce interconnections and infrastructures, project coordination, etc.

In the light of the above, it seems appropriate to analyze the specific case of the access to electricity in WAPP countries by identifying determinants of the access rate. In addition, the analysis will point out in what extent a regional approach of electricity market would be a valuable asset for countries of this part of the world. Hence, the research question can be formulated as follow:

“What are the determinants of the access rate to electricity in West Africa: the case of West African Power Pool countries?”

For this purpose, this paper is suggesting a panel analysis supported by the Hsiao test (Hsiao, 1986) [10], regrouping the 14 countries of the WAPP for a period going from 2002 to 2016, in order to test the effect of variables related to institutional infrastructures, geography and the income of the population. As a reminder, the Hsiao test aimed to know if the panel structure can be accepted, and whether it should rely on an individual or pooled effect. The novelty of the approach and the choice of variable will be helpful for policy makers. The analysis will use secondary data, provided by Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) and the World Development Indicators (WDI).

This research is structured in four parts. First, it will describe the historicity of challenges related to the electricity market in West Africa before evoking prior studies analyzing effect of variables of different natures on the access rate in a second step. In a third step, results of econometric studies will be discussed, and finally, a discussion including strengths and weaknesses of a regional approach of electricity market will be debated.

2. Overview of Challenges Encountered in the Electricity Sector in This Part of the World

Since 1989s-1990s, the World Bank (WB) was already criticizing the management mode of the electricity sector in developing countries by denouncing the lack of “necessary” reforms. Thus, in 1993, the WB conditioned its support (loan) to State-owned monopolies on trade and regulatory reforms, calling for more competition through a process of liberalization (Manibog, et al., 2003) [11]. Indeed, due to lack of financial means, public companies have been unable to provide access and reliable electricity for consumption in most African States. These State-owned companies were vertically integrated and covered generation, transmission and supply of electricity. As defended by Leibentein (1966) [12], for Bös (1994, p 27-49) [13], the bad performances of public enterprises can be explained by the concept of “X inefficiency” which is related to the “labor effort”. This inefficiency value is higher for public enterprises than for private owned ones due to bureaucracy or political interests instead of pure welfare maximization objective. It may also be accentuated by a lack of competition in output market belonging to public enterprises. In such a context, financial institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Monetary Fund (IMF) and the WB have suggested private management and competition. In addition, since natural monopoly is being economically justified in network industries, it remains to State’s responsibility to create conditions comparable to those of perfect competition through regulatory control for ensuring an optimum allocation of resources and make electricity accessible to the greatest number of people.

Consequently, many initiatives have paid attention to the electrification of Africa like many regions of the world to produce electricity and make it affordable. As an example, instigated in September 2011 by the United Nations, the Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) is ambitioning by 2030 to 1) double performance in terms of energy savings; 2) ensure access to modern energy and double the proportion of renewable energies in the energy mix. The SE4All is also encouraging the development of mini-grid via the “Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa” (SEFA). This support was even more necessary as the weak performance in the sector was related to security of supply, production, transport-distribution inefficiency as well as institutional dysfunctioning (Eberhard et al., 2008) [14].

3. Literature Survey

The literature about the determinants of the access rate is not vast. However, the importance of electricity has motivated institutes such as INSEE (INSEE Première, 2016: p 106-109) [15] to focus on this issue and to affirm that resource location, production zones and economic sectors (residential, industrial, tertiary) are important factors. These criteria include neighboring countries in terms of interdependence and security of supply, climatic impact as well as production and network size. The goal in economics is about not only energy, but also health, innovation, education, location of jobs subsequently to the location of enterprises, etc.

Specific parameters have been mentioned by authors such as Banerjee et al. (2015: p 18-19) [4] analyzing the context in India and observing the positive influence of the literacy rate of the house head and the regularity of primary income on the access rate; and a negative influence of monthly expenditure in the decision to adopt electricity or not. In addition, by highlighting electricity consumption in different areas with various access rates, these authors defend that the relationship between access rate and the consumption level is not straightforward. Moreover, the literature suggest social and economic determinants related to both the Human Development Index (HDI), morphology of territories and the concentration of the population that may be different and require specific attention in zoning analyses.

Researchers such as OONA (2010) [6] specifically working on Sub-Saharan countries identified a positive correlation between access rate to electricity in rural areas and variables such as HDI and the income per capita taken as a single parameter; and a negative correlation have been observed with the Gini index. The author has come to this conclusion by a cross-sectional approach considering 24 countries out of the 47 in the Sub-Saharan region.

In the same vein, by considering a panel of 21 countries, Poloamina & Umoh (2013) [16] show by using the ordinary least square method that, the income per capita, the density of the population, performances of the grid in terms or losses and the rural and urban population ratio are relevant factors supporting the access rate to power energy. In the same vein, by a panel analysis covering 31 African countries, Vaona & Magnani (2016) [7] highlight the importance of the workforce and suggested renewable energy as solution for the access to electricity in rurality. Studies that are more specific have been completed as the one of Mwizerwa & Bikorimana (2018) [8] in Rwanda related to macroeconomic determinants, from capital investments to purchasing power, not without giving policy recommendation for generating and distributing electricity economically. For this purpose, they use time series from 1997 to 2012 and Ordinary Least Square for estimating short and long-run effect. These authors concluded a positive effect of the gross capital formation and the average interest rate on agriculture and new external debt. Conversely, other variables such as adjusted saving and added value of agriculture as well as multilateral debt. For improving the situation, they recommend orienting policies toward generation and distribution, sensitization and negotiating multilateral debt.

The ability of population to support energy price is not specific to developing countries and price disparities can be at the origin of an unequal access (Templet, 2000). Indeed, Iniwasikima et al. (2013) [16] used OLS approach for defending the income per capita to remain the most impacting variable in Africa under the Sahara. These authors also underlined many determinant factors such as performances of the grid (losses), population density, and percentage of rural population affect the access rate. A further analysis of their paper mentions the important of government policy that can hinder the access rate. This situation also raises the question of the attraction of investments, which remain a very used option to improve performances in the energy sector.

Dagnachew et al. (2017) [17] mentioned a correlation between the income per capita and the access rate to power energy in Sub-Saharan Africa. They identified technology, off-grids for low consumption levels and central grid extension for higher consumption levels to be determinant for improving the access rate. Also, Morrissey, (2017) [18] observed that international Institutions seem to focus on the way to improve electricity access, and reliability of countries by orienting their decision toward countries which already have higher access rate to power energy. The author defends that to attract private investment and benefitting new technologies for improving the access rate to power energy, government should minimizes risks for investors. In the same vein, he reminds in a report (Morrissey, 2019) [19] that consumer income, investment in infrastructures, education and awareness raising, financial service implying access to credit, policy coordination to be important.

4. Data and Methodological Approach

4.1. Presentation of Data

As described in Table 1, this section aims at describing selected variables provided by the World Development Indicator and Worldwide Governance Indicator [which proposes a qualitative analysis based on the sampling frame from private sector firms, international organizations, institutes and NGOs].

Since data range between 2002 and 2016, this paper consists in analyzing a cylindrical panel.

4.2. Hypotheses of Analysis

Beside regulation which is required for network industries, these hypotheses have been inspired by the literature indicating the influence of the purchasing power, especially those coming from developing countries, and the influence of geographical parameters on special planning.

Hypothesis 1: variables related to institutional infrastructures, regq and goveff, are significant and positively impact the access rate.

Hypothesis 2: variables related to spatial planning, density of the population, the urbanization rate, have a positive effect on the access rate.

Hypothesis 3: the investment level in the energy sector has a positive effect on the access rate of population to electricity.

4.3. Overview of Statistical Characteristics of Variables

In order to better appreciate country’s performance related to selected variables, a descriptive analysis of series presenting values related to average value, skewness, kurtosis, standard deviation and Jarque Bera will be proposed:

1) The arithmetic average value usually written

is calculated by the formula:

; for

(1)

2) The standard deviation is a coefficient measuring the dispersion of a series:

(2)

3) The skewness coefficient is a dispersion parameter measuring the spread to the left or the right of series compared to the Gaussian law:

(3)

4) The Kurtosis describes the shape of a series. It is assessed by the following formula:

(4)

5) The Jarque-Bera test seek to determine whether data follows a Guassian law or not. Its statistic asymptotically follows a law of

with two degrees of freedom. It is expressed as follow:

(5)

4.4. Model and Specification Test

The model of analysis is a panel regrouping the fourteen countries of the West African Power Pool following this theoretical model:

(6)

With the vector of exogenous variables

knowing that:

and

.

The basic model for individual effect is:

(7)

For all the countries (N), the economic interest of the approach is to be sure that the theoretical model remains identical for each country. The minimum condition of application is:

Due to a relatively limited period of analysis (15 years), the panel approach should provide more interesting results than time series. In order to determine the nature of the effect on variables [pooled or individual effect] two tests are proposed to comfort the decision. As reminded in the “introduction” section, the Hsiao test aims to know whether the panel structure can be accepted or not, and to what extent (Hsiao, 1986) [10]. For an individual model, the Hausman test will be completed to testify of a fixed effect or a random effect. The theoretical procedure is established as in Table 2.

The Fisher statistic F1 which is associated to total homogeneity test is:

(8)

related to

and

.

{As a reminder, RSS is the residual sum square of the model, and RSSc is the one of the constrained model.}

In the same way:

(9)

related to

.

(10)

related to

.

The “pooled” approach is denying the individuality or the heterogeneity of data between countries of analysis. Coefficients and constants are assumed identical for all the countries. By supposing a fixed effect, the individuality of data is admitted and each of the countries has its own intercept which does not evolve overtime (time invariant). The random effect value is assuming a common mean value for the intercept. However, no matter the selected model, the theory about homogeneity test allows the analyst the responsibility of assuming the final model he should opt for.

5. Results and Interpretation

5.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Series

Values presented in the following table (Table 3) have been calculated by using formulas (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5). It aimed at putting into evidence some statistical characteristics of variables including all the WAPP countries (14 countries).

Table 3 indicates characteristics of the 14 countries belonging to WAPP. In general, the rate of the population living in urban area has increased in most WAPP countries and has remained more or less stable in Niger (16.3%) over the period considered. This trend could reflect an increasing rate of urbanization or in many cases an urban exodus of rural population seeking for work or a better living environment (access to care, electricity, running water, communication…). These explanations should be put in parallel with a positive average and relatively high annual growth rate of the population, 2.78% for all the countries of the analysis.

![]()

Table 3. Descriptive analysis of series of countries, members of the WAPP.

The level of corruption in general seems quite high and the performance of Côte d’Ivoire (−0.92) is lower than in the average value of all the countries (−0.73). The density of the population largely varies depending on country’s territory and the size of the population. Very large countries such as Mali and Niger have the lowest densities, or very large population such as Nigeria which presents the highest population density.

In 2016, with respectively US$ 2175.67, US$ 1535.06 and 1517.49, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana had the highest incomes per capita. These countries were also benefiting the highest investment levels. Similarly, there are significant differences in income between countries especially between these three counties and the others countries of the sample. Furthermore, volatilities that are observed can be explained by different levels of economic and social performance, and political challenges.

An overview of series shows that there are significant differences in terms of values between countries. Most of the States have poor performance (negative values) for indicators of reguq, rullaw, polistab and govereff. Indeed, institutional infrastructures are generally fragile and reflect depending on the country, of political instability, security problems and the weakness of judicial institutions. Although efforts are essential for all the countries of the analysis, regulatory environment proposed by Ghana seems to be the most efficient although the average performance of this country is negative (−0.07).

5.2. Homogeneity Test

According to the Hsiao test procedure posited in Table 3, the panel structure in a common model regrouping all the countries belonging to WAPP cannot be supported by the data. It means that some values coming from one or many countries are perturbing the model. Therefore, in order to improve this model and having a structure accepted as panel, Ghana and Nigeria have been removed from the sample. The result homogeneity test is as follow.

As suggested by the Hsiao approach (Table 4), the panel should be treated as a pooled model as presented in next table (Table 4). This pooled model can effectively be assumed based on the existence of regional institutional infrastructures such as a regional regulator [ERERA] and the force of its decisions vis-à-vis national regulator. Also, the regional market can be a useful parameter to support the development of electricity sector as it is willing to be for ECOWAS [Economic Community of West African States] as a unified economic and political sphere.

The matrix of correlation reveals the high correlation between govereff and the reguq (0.82). This value requires remaining careful while regressing to avoid collinearity risks and misinterpretation of results.

An effective linear relationship between the neperian logarithm of the GDP per capita and the access rate to electricity (0.773) can be anticipated (Table 5). Likewise, possible interferences can make possible effects of suggested variables.

![]()

Table 4. Results of the Hsiao test.

![]()

Table 5. Matrix of correlations for selected variables (WAPP countries without Ghana and Nigeria).

As a reminder, Ghana and Nigeria have been removed from the list of countries when specifying these models. Results indicated in Table 6 show that constants of these models are very high and variables related to institutional framework considered in a pooled approach has a positive impact on the access rate. Indeed, an integrated and coherent energy policy approach into an integrated economic space with a diversity of primary resources can give confidence to investors, improve the scale effect, and promote affordable power energy. Elasticities of reguq and govereff are relatively high and a collinearity effect can be suspected in the model 1 regarding the high correlation value between reguq and govereff (0.822).

Depending on the selected variables and whatever the model, lgdp_cap remains the most significant factor with a minimum elasticity value of 16.81 and a maximum of 22.13. This result is consistent with the findings of Iniwasikima et al. (2013) [16] defending the income of the population as the most significant parameter to support investment and operation costs related the electric system. Lemma et al. (2016) [20] remind that there is no consensus about the casual relationship between the access to electricity and economic growth. Nonetheless, one important challenge for developing countries remains the purchasing power of population mainly in rural area for supporting electricity charges which vary depending on the nature of the primary resource (renewable or not). Though the same interpretation cannot be done about the slope of variables such as urban_pop_r and pop_density which are not as high as lgdp_cap, they remain significant and important.

![]()

Table 6. Result of multivariate regressions.

***, **, *denote significance respectively at 1%, between 1% and 5%, and 10%. T value is in parentheses. For F-value, p-value is also in parentheses.

Evidently, the question of the structure of the population is a matter of interest for demographers of all disciplines as well as planners. Indeed, studies about urban population rate or population density respond to strategies related to space management and concern both economists, geographers and sociologists. Many leading institutes have taken an interest in this issue and have come to some fairly long-awaited conclusions. According to the national institute of statistics and economic studies in France (Insee première, 2016) [15], access to services is evolving faster in areas of high population. It recalls that pop_density is an important parameter for spatial planning in terms of access to infrastructure and tensions in the housing market. Clearly, there is a risk that artificially low density surfaces will grow faster than populations by occasioning a need for road infrastructure and high energy requirement. The “location” parameter involves the need for measures and arrangements to be implemented for effective access to important communication and energy infrastructures. Nowadays, the trend is toward homogenization or an analysis of the density of the population which minimizes the cost of public service facilities.

Depending on the countries, standards of urbanism and criteria of erection in municipality are different. The larger and more uneven the municipality in terms of reliefs, the more expensive the access to electrical energy, and the supplied energy suffers from losses by Joule effect during transport. In developing countries, the existence of electric infrastructure is specific to cities and may be considered as a distinctive factor of rural environment. Thus, the access rate remains positively correlated with urban development or growth, and explains the reason why this rate is higher in urban area than in rurality. A rigorous and adapted urbanization policy is essential to accelerate the access to electricity for the population. The electricity access criterion can very often make it possible to regulate the pressure on the cost of housing. In addition, a growth rate of the population into an inert space is likely to facilitate access to energy even if this assertion is to be compared with the “relative” geographical spread likely to borrow space dedicated to agriculture or other economic activities. In such a context, the access rate to electricity should increase enough to contain the population growth. Otherwise, the number of persons without access to electricity increases.

6. Discussion

In this section will successively be discussed problems faced by West African countries, economic and political expectations in terms of necessary reforms, role of players, and a focus will be done on investment and supra national approach for improving the access rate.

6.1. The Necessity of Urgent Economic and Political Measures

In many countries, governance as well as political and economic orientations of the electricity sector very often requires adaptation needs in the implementation of reforms. Indeed, these reforms influence the performance of the electricity sector insofar as there is a relationship between the adoption of reforms by a country, the quality of its governance and the performance of its power sector. For the World Bank, it means to highlight structural and institutional conditions resulting in an improvement of performances and for consumer welfare (Rossi and Eustache, 2008) [21]. In the same way, corruption, political interests and governance problems explain failure of reforms.

Likewise, macroeconomic arguments such as inflation rate, exchange rate of commodity prices and monetary imbalances are modulating the trajectory of reforms. Obviously, political instability or the weakness in the availability of a qualified workforce in quantity and quality cannot be excluded with regard to factors describing the causes behind the delay experienced by the African countries (Tehero and Aka, 2020) [22].

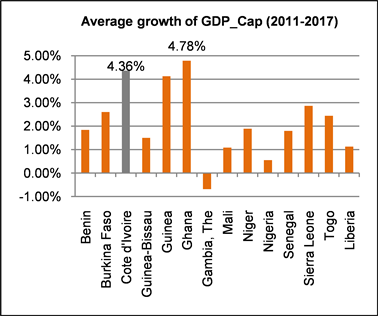

Economic outlook of WAPP countries are supposed to evolve in the future in terms of wealth, and the African population tends to become a quarter of the world’s population by 2050. This evolution pattern is important because the dynamic of the population and the economic growth, around 5% since more than a decade, may affect energy demand. The GDP growth of Africa according to the IEA simulation will range from 5.2% to 5.5% between 2021 and 2030.

Access for all to power energy requires identifying vulnerabilities and proposing appropriate measures and mechanisms. In this prospect, Nigeria has introduced new provisions facilitating access to electricity. In Côte d’Ivoire, the decision to spread subscription fees over more than a decade facilitates the access to energy for poor population, even if electricity cost remains high compared to the purchasing power. Niger reduces the delay before getting connection by reducing procedures. As a reminder, the necessity of urgent measures is not typical to this region since by evoking the case in Bangladesh, Taheruzzaman and Janik (2016) [23] recommend innovation to improve the access to reliable energy, mainly in rurality by encouraging renewable energy and small grids.

Besides, essential measures to be taken into account must not only be cyclical, but also structural. Thus, the development of the regulatory framework, operational regional markets, the fight against fraud, a qualified labor force and the development of interconnections are likely to increase the size of the markets and to limit investment risks with respect to the economy of scale in the power industry. It should be admitted that countries having high performances in terms of access rates or quality indicators have benefited from a coherent and sustained political will or favorable historical context. In this prospect, the quality of institutional infrastructures can enhance the access to public services such as electricity (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2008) [24], by improving impartiality, predictability, consistency of economic environment and enforcing rule of law (North, 1992) [25].

The lack of means of control and the weak regulatory framework increase the risks of asymmetric information between the regulator and the firm. In addition, a survey by Gallager and Wykes (2014) [26] highlights the lack of access to important information by players including populations. They evoked prejudices about energy costs (mainly about renewable energy) or the translation of some important information into local languages. Public policy implementation and acceptability must be economically efficient and socially fair (Gunn, 1978) [27]. However, administrative burden and the low level of sophistication of demand with the adjunction of the lack of infrastructures represent obstacles to planning, implementation and monitoring of energy policies in Africa (Ernst and Young, 2013) [28].

In such a context, it seems essential to clearly define the roles and responsibilities according to a well-defined action plan.

6.2. Role of Players

Envisaging access for all to electricity requires a holistic analysis. Consequently, players may influence technological innovation (smart meters, prepaid meter…), propose a financial business model that facilitates the emergence of innovative models, with a view to ensuring a long-term supply-demand balance. In this aim, different groups of key players have an indispensable role in the development of power sector.

Roughly speaking, the sensitivity of the product “electricity” requires vigilance from the government and the civil society in their commitment to transparency in the financial management of the sector. It is also necessary for governments to improve the expertise of the labor force that would result from an educational and academic system able to face contemporary challenges. These players can also influence policies, behaviors and legislative action in favor of standards, the implementation of solutions adapted to the specificities of populations and affects the attitude of the consumer. The civil society acts as an intermediary between the government, private sector and consumers, more specifically in favor of the most vulnerable categories of the population (Gallager and Wykes, 2014) [26].

However, the political will remains the starting point for improving access with probably a greater share for renewable energy. For instance, an independent regulator and incentive will generate transparency, give confident to investors and encourage the deployment of new technologies… This objective requires good coordination and mobilization of efforts. The monitoring and the experience feedback remain indispensable exercises for a better long-run performance.

As a player, the private sector can make a major contribution for the acceptability and operational status of standards, and participate in the development of business models. Indeed, the investor is the appropriate player to assess regulation efficiency and participate to the definition of an adequate regulatory framework. In its analysis, the firm defines its strategy with greater confidence when the mechanisms linking public institutions are clear and concise (Riccardi, 2009 from Reenock, 2008) [29]. For the sake of simplification, international financial institutions may be considered as belonging to this category of stakeholder.

6.3. Investments in Power Infrastructures

Basic needs related to access rate and reliability require improving and extending infrastructures (Kanagawa and Nakata, 2008) [30]. Nevertheless, financing the access to electricity in Africa requires not only private external investment but also the mobilization of domestic savings (Brew-Hammond, 2010) [31]. However, the insufficient size of the markets [taken individually] and the weak economies symbolized by the low purchasing power represent the main handicaps (Heuraux, 2011) [32].

One specificity of power infrastructures is the lifetime of installations, which can reach horizons of about fifty years. Lock-in capital corresponds to several times the turnover of companies operating in the sector. Such a situation is likely to increase the level of risk incurred by the players whose commitment remains sensitive to the economic environment (Gollier et al., 2011: p 41-43) [33]:

・ Macro-economic cycles, conjunctures, raw material prices, prospect of demand…;

・ The nature and size of the investments;

・ The nature of players (public, private, …).

Investment needs related to production and transport infrastructure remain very high given the aging of existing infrastructures and growing demand that remains a corollary of development and economic growth. Due to economic constraints for achieving a universal access to power energy in Sub-Saharan Africa, the share of private investment for improving grid performance seems to increase vis-à-vis traditional public fund (Sy and Copley, 2017 [34]; Lee and Doukas, 2018 [35] ). For this purpose, financial players such as the African Development Bank remains a strategic partner (AfDB, 2016 [36]; Lee and Doukas, 2018 [35] ).

6.4. Strength and Weaknesses of a Regional Approach of Electricity Market

A common energy policy might be an interesting option for the energy independence and the development of the electricity sector in West Africa. Indeed, a resilient and affordable energy system will rely on a diversified production and variable energy sources that should be better analyzed and managed systemically.

The development of the electricity sector does not depend solely on technologies that requiring strong and coordinated political support, but also on how it is managed as a whole. For this reason, the challenge presented to the governments of each of [WAPP] member States is to propose a common vision favoring the integration of national electricity systems and planning for an adequate regulatory framework.

6.4.1. Higher Economic Potentialities

West African countries as a whole represent a bigger market in terms of potentiality. In 2017, countries member of the WAPP represented 367,019,498 persons according to the World Development Indicators. The biggest country in terms of population is Nigeria more than 190 million of inhabitants while Côte d’Ivoire had around 25 million, and smallest countries like Guinea-Bissau had less than 2 million of inhabitants. In terms of surface area, biggest countries are Mali with 1.24 km2, Niger with 1.2 million km2 and Nigeria 923,768 km2. Côte d’Ivoire is surface is 322,462 km2, so a population density of 76 inhabitants per km2 and resp. 210 and 143 inhabitants for resp. Nigeria and Togo.

In terms of private investments attractiveness in the energy sector, Côte d’Ivoire recorded $US 788 million from 2002 to 2017.

Graph 1 shows that countries like Ghana and Nigeria attracted more private investments while other like Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau or Niger did not capture any private investment at all during that period.

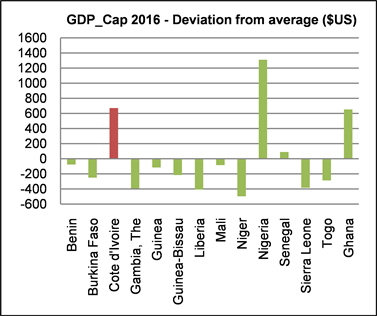

Another important factor is the GDP per capita. As indicated on Graph 2, countries benefiting the highest private investment also have the highest income per capita. In addition, WAPP countries do not have the same production opportunities and means. Exchange in electricity seems to appear as an opportunity to improve energy supply. As an example, during the year 2016 Côte d’Ivoire exported 1655 GWh of power energy to Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Liberia, Mali and Togo while the country imported 18.2 GWh essentially from Ghana (Anaré-CI, 2016) [37].

6.4.2. A Diverse and Varied Energy Potential at the Regional Level

First, the Sahelian zone has a vast area for the development of solar energy (Mali, Niger…). Niger is also the second largest country in terms of uranium reserves which might be necessary for the production of electricity. However, skilled human resources and the geostrategic delicacy of nuclear energy remain the main challenges. The significant potential of geothermal energy in the basin of the Volta can contribute to the diversification of power generation.

Second, there is a huge potential for hydrocarbons (Nigeria…), for biofuel development in semi-arid areas (Burkina, Mali, Niger) even if it raises the question of ethics. Also, many countries, mainly coastal countries have a high hydroelectric potential (Iwayemi, 1983) [38].

Graph 1. Sharing of private investments in Energy sector in WAPP from 2002 to 2017. Source: WDI (2018).

Graph 2. GDP information about ERERA countries. Source: Author, from WDI (2018).

As a reminder, the Protocol A/P4/1/03 adopted by ECOWAS Heads of State is based on mutual benefits to increase investment and develop regional energy trade. Networks of West African countries are generally small, often in poor condition, and production means are sometimes expensive. Economies of scale are possible and the quality of the network is improved due to interconnections that facilitating the use of other countries to remedy failures in a country or give access to electricity to population living near borders. The ERERA in such a case plays the role of a good coordination between member countries by also facilitating necessary reforms for an efficient regional market.

6.4.3. Limits of Regional Integration in the Power Sector

Limitations of regional integration are the “national concern” about energy independence and the lack of restructuring in some countries. Furthermore, it seems difficult to determine the optimum level of integration since experience in some developed countries shows that openness to competition has generated an increase by 10%, which has led to better cost control and quality performances.

The electricity value chain is not segmented enough and electricity from local generation is often more expensive than imported for some countries depending on the nature of the primary resource. This situation results in a low motivation to achieve the production objectives of each country and a strong interdependence between non-self-sufficient countries.

Definitely, political stability remains an important criterion in the implementation of investment projects. This observation remains verifiable with regard to the long political crisis between 2002 and 2010 in Côte d'Ivoire. The majority of investments were postponed and conditioned by political stability. Another example is the security context in the Sahel. Finally, it is important to note the high dependence of investments in network infrastructures vis-à-vis private investors.

6.5. The Deployment of Off-Grids (or Small Grids) for Increasing the Access Rate Mainly Rurality

Mini-grids or off-grid power models in general―especially those using modular small-scale renewable energy technologies―are becoming increasingly attractive and cost effective for remote communities (BAD and ASEA, 2018: p 19) [39]. Authors such as Khennas (2012) [40] are suggesting mini-grid as an interesting approach for rural electrification. This approach of small-grid consists in a small “local” network coming in “off-grid” or in complement to a central grid and serving customers. In general, a design based on a centralized network is the least expensive but it is essential to associate an annex or small grid network in order to facilitate access to electricity to a larger part of the population mainly in rurality. Indeed, mini-grids are presenting a limited economy of scale and are very convenient for new technologies deployment or renewable energies in a context of lower capital cost despite a high price of electricity (Morrissey, 2017: p 30) [18].

The expansion of these small-grids is facing challenges (Manetsgruber et al., 2015: p 18) [41]:

・ Uncertainties related to legal and policy framework;

・ Lack of investments due to economic and finance profile;

・ Efficacy of regulatory instruments.

In West Africa, mini-grids associated with renewable energy are being tested or implemented in many areas and the interest for off-grids seems to become an important option considered by governments. In such a context, the regulator has to take into account the “decentralization” of network systems increasingly integrating mini-grids in full swing to ensure economic viability mainly in low-density localities or in their cohabitation with the main network.

Mini-Grid Challenges

The future of micro-grids or nano-grids in WAPP countries deserves to be analyzed in the light of the experiments carried out. Indeed, performances in terms of cost of micro-grids depend on the nature of the production mix and geographical spread. Therefore, there is a population and geography effect to be considered. Moreover, the low purchasing power of rural population is handicapping the deployment of off-grid system. Therefore, general policy should aim at envisaging an autonomy in the management mode by local population and an economic activity generating income for supporting, in part, maintenance charge; or conceding their management by granting licenses, etc.

7. Conclusion

Despite the existence of primary energy resources, the African continent continues to lag behind in terms of power energy infrastructures and access rate. As a reminder, electricity has a positive effect on education, health, comfort and housing of enterprises or basic public services in the area (health, police, etc.). It also has a positive impact on employment and real estate development. Prior studies as the one of Kanagawa and Nakata (2008) [30] proved the impact of the access rate to electricity on socio-economic indicators in rural area and noticed a direct effect on literacy and health, and indirect effect on equality of genders and poverty reduction. An important parameter remains the GDP per capita since whatever the model, the slope of this variable remains the highest. The problem may not only be the availability of electricity, but income regularity, [high] connection charges or houses that do not respect requirements for connection in safe condition. This result is not singular to this region of the world since energy development is suggesting heavy investments which will have to be recovered from tariffs.

In order to respond to energy challenges, WAPP countries must enhance the access rate to electricity and extend existing infrastructure; they should also improve the regulation and the governance of the sector. Therefore, achieving these objectives requires coherent and sustained measures. Indeed, energy requirements oblige countries to set up quality indicators but also coherent policy of mutualization of assets and minimization of investment risks at different scales [regional, even supra-regional]. Both cyclical and structural policies are needed to ensure access to electricity for all, improve the quality of service, raise the level of expertise of workers in the sector, attract investors and provide an adequate regulatory framework. Initiatives on the supply are necessary by setting up new production capacities and a structural overhaul of the electricity interconnection and demand-side actions by integrating energy efficiency.

AfDB’s “New Deal on Energy for Africa (2016-2025)” aims to cover 100% of the urban population and 95% in rural areas by 2025. This ambition involves increasing and improving production and transport infrastructure [off-grid or grid connected] which remains important since the African population growth is around 2.4%.

By focusing on the West African context, it has been proven that population density facilitates the electrification process since a more significant number of persons are benefitting electricity in a restraint area [the energy not supply increases with the distance due to losses related to the performance of the network]. Countries having a high rate of urban population benefit a high access to electricity. As a network industry, Electricity sector is characterized by a scale effect. This specificity explains the reason why the density of the population has a positive effect on the access rate. When population density and rate of urban population density are high, it does not require heavy network infrastructure to reach a higher number of consumers.

Energy independence in West Africa requires a common energy policy. The need for an integrated market would require the establishment of a research center based on objective criteria and an integrated regulatory framework. ANARÉ-CI (2017, p 80) [37] is reminding that the institutional framework should be appropriate for efficient pricing, and tax incentives. Indeed, the quality of regulation gives confident to investor. Furthermore, as suggested by the HSIAO, the pooled analysis including the 14 member-States of the WAPP testifies the importance of a regional approach in term of inclusive policy, access to investment and economic potentialities. Therefore, this paper reveals that West African countries have to make significant effort in terms of governance indicators. Individuals and average score related to corruption, regulation, judicial framework, and government effectiveness are not good and have to be improved.

Remembering, GEI2 (2014) report defend that universal access to electricity will not be effective if the situation remains unchanged in so far as electricity demand is expected to increase even in an assumption of more energy efficiency of equipment or processes. That report recommends “long-term thinking, stable and clear regulation, strong collective commitment”. One of the biggest challenges is the reduction of losses on the transmission and distribution network, but also, the use of secondary network (off grid) to by-pass the main network and increase the access rate in rural area.

Moreover, since there is no difference between household with access to electricity but enduring more than twenty-one hours interruption a day and household without electricity, it appears important to improve quality indicators.

NOTES

1This institution is implying 14 countries: Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Niger.

2Getting Electricity Indicators―Doing Business report―utilities view electricity access as a priority..