Psychology 811 2011. Vol.2, No.8, 811-816 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.28124 Decision Making Styles and Adaptive Algorithms for Human Action Mauro Maldonato1, Silvia Dell’Orco2 1University of Basilicata, Potenza, Italy; 2University of Macerata, Macerata, Italy. Email: mauro.maldonato@unibas.it Received May 11th, 2011; revised July 18th, 2011; accepted September 21st, 2011. Without human beings’ ability to choose―and in such a way give order to a universe which, in the beginning, must have presented itself as a chaotic mass of data without clear structures and regularity―evolution would have been unthinkable, even more inconceivable if one considers the fact that the adaptation to that universe must have taken place on the basis of incomplete, fragmentary information and above all starting from limited cognitive capacities and restricted time limits. In order to respond to the challenges of the environment, an indi- vidual had to first of all be quick: quick in the reaction to the attack of a predator and in the gaining of an escape route, in deciding how to pursue pray, in obtaining gains from territory that others were using at that same mo- ment, in the selection of a partner and of a place in which to take refuge and so forth. Therefore, if it is true that evolutionary pressure urged the human mind to accumulate information by means of a significant quota of ra- tional decisions, the vast majority of human choices have been favoured by ecological decision making strate- gies. Keywords: Naturalistic Decision Making, Ecological Rationality, Fast and Frugal Heuristics, Decision Making Styles Introduction In the last half century, a growing amount of experimental research on decision making behaviour (Hastie & Dawes, 2001) has investigated the systematic deviations from the axioms of neo-classical economic theory, which is based on the hypothe- sis of perfect or instrumental rationality (Bernoulli, 1738/1954; von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1947). Around the middle of the 1900’s, while many economists were embracing Friedman’s as if perfectionist thesis (1953)―according to which individuals behave as though they were able to perform the complex calcu- lations required by the normative model―Simon opened up a gateway in psychological and economic reflection by remark- ing upon the implausibility of an abstract rationality which denies both the limits of the external surroundings (task envi- ronment) and the imperfect cognitive structure of human beings. A decision, according to Simon, is not the mere algorithmic processing of a set of data, but rather an adaptive process which allows one to reach a dynamic balance between an efficient, quick and economical course of action, the progressive adjust- ments of the solution and, finally, the configuration that reality should have following the solution of a problem. Simon’s ideas would open up the way to a vast series of experimental research projects on the “deviations” of individual behaviours from the predictions of neo-classical economic theory: research that would be powerfully relaunched by Kahneman and Tversky, who would show with precision the non-causality and sys- tematicity of such deviations. As is known, at the foundation of Simon’s bounded rationality is the idea that human decisions are not governed by logico-formal procedures, but by heuristics: cognitive devices potentially the cause of distortions (biases), but extremely efficient systems used by the human mind to reduce the cognitive load and respond quickly and efficiently to problems presented by the environment (Hamilton & Gifford, 1976; Nisbett & Ross, 1980). They are, in other words, un- planned informal reasoning strategies, which allow individuals to make sustainable choices for the computation and the proc- essing of information, choices fitting with the complexity of the situation. If neo-classical theory considers information to be a scarce and negotiable good, by the same standards as any other ge- neric good or factor of production, several authors (Marschak & Radner, 1972; Hey, 1979) point out instead that information is not always scarce but above all that, in conditions of overabun- dance, it could go unperceived and remain unprocessed by de- cision makers. Overabundance, complexity, heterogeneousness and limited subjective interpretative capacities call the neo- classical analysis of information back into question (Stigler, 1961), according to which information can be measured in terms of a cost-benefit analysis. Given that incoherency in as- pirations and cognitive incompleteness―generated by the scar- city or the excess of the information to be processed―chara- cterize the most wide-ranging contexts of individual choice, the decision maker must adapt to flexible conditions using learning operations which reduce the complexity of the calculations required in order to make a decision. In the descriptive ap- proach to decision making individual choices are determined not only by a few complete and coherent objectives and by the properties of the external world, but also by the knowledge that decision makers have of the world, by their ability to call up such knowledge at the right moment, to formulate the conse- quences of their own actions, to foresee the course of events, to face uncertainties (including those deriving from the possible reactions or responses of other actors), and finally by their abil- ity to choose between their own various competing needs (Simon, 2000). In this sense, because of the high adaptive value of the forms of reasoning which determine it, bounded rational- ity cannot be considered irrational, nor can it be called upon solely to explain human error. As Selten (1998) observed, it is possible to construct theories of limited rationality in which  M. MALDONATO ET AL. 812 behaviour, while not being optimal, is anything but irrational. If in an absolute rational order the alternatives are given, in a limited rational order they must be invented each time by the agent, in a process which generates many possible courses of action (Simon, 1997). Whether dealing with a company, a bio- logical species or an individual, adaptation to one’s environ- ment, according to Simon, always depends on a heuristic search and on forms of local optimization or satisficing (Simon, 1983). The search for alternatives ends with the alternative that, ac- cording to the circumstances, best satisfies our objectives and needs. In this sense, an evolutionary theory of rationality must include a search theory which does not adhere to the rules of “normative arrest” (March, 1994)―according to which the search for alternatives ends only after having reached an ideal optimizing result―but rather one that is concentrated on per- sonal aspiration levels. The Paradigm Shift: Heuristics and Biases Approach Behavioural Economics, which originated in Simon’s re- search, attempts to integrate the classical theory of rational choice with new hypotheses coming from psychology―in par- ticular from experimental psychology (Mullainathan & Thaler, 2000)―thus shifting the attention from substantive rationality to procedural rationality. Search and satisficing (Simon, 1979) are the key terms of the limited-rationality decision making process: agents review, one after another, the decisional alter- natives available and stop when such a search reaches a certain threshold of satisfaction (even if this is only an implicit one). When faced with an economic decision, an individual behaves like a chess player who has to choose his next move. Both an economist and a chess player reason according to procedures. The winning strategy is however constructed gradually and not in advance, according to a tree-shaped schema, and reformu- lated at each step of the game based on the adversary’s coun- termoves. Moreover, in economics, as in the game of chess, success is often due to the fact that human beings are simply equipped with good intuition and efficient judgement (Simon, 1983). It is no coincidence that the famous Russian chess player Kasparov (2007) maintains that in a game of chess, as in real life, it is not always possible to analytically assess every single possible action. Every move can in fact lead to an infinity of possible positions, each one of which is the result of a chain of cause and effect which must be carefully examined. In many cases, especially in situations where time is limited, emotion and instinct can cloud even the sharpest strategy and suddenly transform a chess match into a game of fortune. With the Heu- ristics and Biases Approach research program, developed by Kahneman and Tversky in the 1970’s, the concept of heuristics, already introduced by Simon, took on experimental validity, becoming the mainstay of a realistic model of the rational agent. This program consists of experimentally subjecting decision making problems, opportunely concocted, to samples of indi- viduals in order to verify whether or not they reason and make decisions according to rational criteria. In the eyes of Kahne- man, Slovic and Tversky (1982) heuristic judgement is the only practical way to evaluate uncertain elements. Unlike formal calculation, the heuristic evaluation of probability is based in general on immediate solutions which consider only some of the factors at play: the particular characteristics of the object under evaluation, the way in which the problem is formulated, the clarity with which the situation is described and so forth― factors which influence separately or in a combined way on decision making behaviour. If the results of such studies have, on the one hand, supplied important clues as to the nature of human cognitive processes (contributing to the de-construction of the homo oeconomicus model), they have on the other hand given the concept-term “heuristics” negative connotations be- cause of its strong connections with the term bias. Bias, in fact, is commonly defined as the difference between human judge- ment and a rational “norm”, often considered as a logical or statistical law of probability; almost as though, once the biases within human reasoning are avoided, one could reach optimal decisions. The double process theory of Kahneman and Tver- sky is based on the idea that people, when expressing an opin- ion or a decision, use two different cognitive systems: intuitive processes (system 1) and analytical processes (system 2) (Kah- neman & Frederick, 2002; Stanovich, 1999). System 1 is primi- tive, fast and associative; system 2 is slow, serial and deductive. System 1 produces a rapid response which can subsequently be approved, corrected or substituted by system 2 (even though this is rather infrequent). During the message comprehension process the attributes highly accessible to system 1 (similarity, availability, affection) become heuristic attributes for the final decision. In other words, intuitive judgement comes about if one uses a very accessible attribute (processed by perception or by system 1), and if the inspection by system 2 fails. In other terms, rational behaviour can still be defined as such if, and only if, it conforms to the laws of logic and to the theory of probability. Towards an Ecological Rationality The recognition of these limits has fostered the conditions for a different approach to the study of decisions. At the end of the last century Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) was born, a paradigm with the objective of studying the way in which peo- ple make decisions and perform complex cognitive functions when dealing with real world problems: namely in situations characterized by time limits, incomplete knowledge of the al- ternatives, emotional tension, uncertainty, poorly defined ob- jectives, high stakes and decision makers with various levels of experience. The study of decision making does not pertain to the mere choice among the available alternatives on the basis of their Expected Utility, but to the natural procedures followed by decision makers before carrying out an action. Such procedures are composed of three basic principles: • The decisions are made based on a holistic evaluation of the potential actions, an evaluation performed on the basis of the available options as well as on the comparison be- tween the specific characteristics of those options (Lip- shitz et al. 2001); • The decision maker chooses to act not on the basis of the search for and the detailed processing of the alternatives, but through a process of situation recognition (the recog- nition-based heuristic) which is carried out by comparing the alternatives and the potential courses of action among themselves (pattern-matching) based on a few criteria of acceptability; • The decision makers do not look for an optimal solution, but adopt a satisficing choice criterion (Klein & Calder- wood, 1991). Gigerenzer (2001) has pointed out how homo heuristicus loses out, in terms of efficient behaviour, in comparison with homo oeconomicus only when the axioms and the standards of normative rationality are involved. The capacity of individuals to make adaptive decisions―modifying their own cognitive  M. MALDONATO ET AL. 813 strategies in relation to the context and to the structural muta- tions of the decisional problem―proposes to the decision maker a framework that is sufficiently optimistic in terms of the rationality of the behaviour (Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). This inspired Gigerenzer to propose a revision of the classical concept of heuristics. If for Kahneman and Tversky heuristics are cognitive strategies (the cause of biases which compromise the making of correct decisions with regard to normative stan- dards) for the German psychologist heuristics are perfectly adaptive fast and frugal rules which function within the con- straints of the environment (limited time, insufficient informa- tion etc.) and the cognitive-computational limits of the decision maker (Tietz, 1992). The correspondence between the decision maker’s mind and the environment is the turning point for an ecological redefinition of rationality (Todd & Gigerenzer, 2000). Fast and frugal heuristics consist of three fundamental rules: • The search rule: this defines the principle according to which heuristics guide the search for information and for decisional alternatives within a limited timeframe (the search is not extensive as in the theory of rational choice) and without performing calculations; • The stopping rule: this includes the principles which specify how and when the search procedure must come to an end. In line with Simon’s theory of bounded rationality, given the cognitive and environmental limits of real world problems, the search is ended on the basis of satisficing processes (Richardson, 1998) and not optimizing ones; • Heuristic principles: fast and adaptive decision making procedures which, despite their frugal nature, can be very accurate compared to classical algorithmic computation. The so-called Take the Best heuristic, proposed by Gigeren- zer (1997), outlines a satisficing choice criterion, although it is mostly used for decisions between two specific objects. This procedure is represented by a grid (Figure 1) in which the col- umns indicate the alternatives and the horizontal lines indicate the criteria or cues. The alternatives (a, b, c, d) are examined two at a time through criteria or cues organized in a decreasing order on the basis of the validity that the agent assigns to them. The basic criterion is called recognition and is subjective. The following cues (in the example: cues 1-2-3-4-5) are of an ecological na- ture and are related to the specific context of the choice. In the example the values assigned to the cues are: positive (+), nega- tive (−) or uncertain (?). The procedure works in the following way. Let us suppose that an agent must choose which company, A or B, has the greatest number of employees. On the basis of the first criterion (recognition) the agent must only “recognize Figure 1. Take the best algorithm. Source: Gigerenzer e Goldstein, 1996. (+) or not recognize (−) the object”. We will suppose, as in the example, that the agent recognizes both of the objects. In such a case, on the first line, recognition, we will have two + signs. At this point, because the criterion of identification does not allow the agent to distinguish between the two objects, she moves on to consider the first “ecological” cue (cue 1): “the company has/ does not have sub-units”. The agent is aware of the fact that company A has sub-units and that company B does not (on the line cue 1 we will have one + and one –). In such a case the agent does not need to proceed further: company A has more employees than company B. In other words, only four values were considered (the grey shaded area in Figure 1) out of twelve. Suppose at this point that we have to repeat the whole procedure for the objects B and C. As in the first case, both pass the recognition test (two + signs on the first line). The agent thus moves on to the first cue (cue 1). In this case she knows that company B does not have subunits, but does not know whether company C has any or not (?). In such a case she proceeds to the second cue: for example “the company invests/ does not invest in the retraining of its personnel”. The agent knows that company B satisfies this cue (+) and that company C does not (−). At this point the criterion allows for the agent to distinguish between the two objects and the process stops. Six values have been considered (the area within the dotted line) out of twelve. If, for example, for the first criterion the agent had not recognized one of the two objects (C and D) the choice would have fallen to the recognized object and the process would have ended there. It is evident that if the agent does not recognize the object she cannot act on any cue (the column under the object C is in fact made up of only?). The decision making process is therefore governed by an identification heu- ristic: the only condition necessary for making a choice is that one of the two available options has not been recognized. A criterion that allows for the differentiation between two objects is the best compared to other criteria. The distance between this approach and the inferential ap- proach in which all of the available attributes are considered in a compensatory way is evident. Here, instead, there are no mathematical calculations to be performed or averages to be calculated, because the characteristics of each option are con- sidered in a non-compensatory way. This type of “fast and fru- Figure 2. Flow diagram of a fast and frugal heuristic: take the best.  M. MALDONATO ET AL. 814 gal” heuristic search is based on a stopping rule called one rea- son, according to which the choice of an option is based on only one cue and on information that satisfies an optimal crite- rion for the decision maker (Figure 2). In such a case one can speak of ignorance-based decision making, which generally represents the first phase of all of the one reason type decisions. The importance of this family of heuristics resides in the very type of ecological rationality implicit in their process. In line with Simon’s structure, in particular with regards to the adap- tive and procedural aspect with which agents choose their own courses of action, Gigerenzer proposes the metaphor of the Adaptive Toolbox (Gigerenzer, 2001). This is a sort of “tool- box” composed of a repertory of evolved heuristics which pos- sess the following characteristics: • They are specialized for certain tasks; • From a computational point of view they are simple, fru- gal and fast; • They do not have the problem of formal coherence, but rather that of adaptive efficiency; • They resolve here and now problems related to the chal- lenges presented by the environment (obtaining food, avoiding predators, finding a partner and a secure refuge, but also, at a higher level, exchanging goods, making a profit and so on). Every individual chooses to use, as necessary, the heuristic best adapted to the task to be completed; during the completion of the task, the heuristic may also be substituted. In order to describe the nature of the “toolbox”, Gigerenzer (2001) uses the image of a mechanic and sales person of used parts in an iso- lated area, who possesses neither the tools, nor all of the neces- sary spare parts, but who when faced with a problem tries to find a solution with the tools that he has at his disposal. “These evolved capacities―explains Gigerenzer―are the metal from which the tools are made. A gut feeling is like a drill, a simple instrument whose force lies in the quality of its material” (2007, p. 63). Such heuristics function well in natural situations, where the presence of limits in terms of time, knowledge and compu- tational capacity make the adoption of fast and efficient strate- gies preferable. In reality, liberated from their traditional nega- tive connotations, heuristic strategies have become more than just deviations from a rational “norm”. They respond to an ecological and adaptive rationality which allows individuals to efficiently face situations of uncertainty, risk and missing in- formation typical of the reality in which we live. Decision Making Styles Another model developed in the domain of NDM is known as the recognition-primed model. Analyzing the decisions of experts (doctors, military commanders, fire fighters, pilots and others) Klein and colleagues (1993) have shown how in critical situations these experts do not follow normative models. In such contexts the decision making process is characterized by drastic time limits and, in the case of a missed or erroneous decision, by grave consequences. If, for example, in an emer- gency situation the head fire fighter does not decide efficiently and in a few seconds what to do, he risks putting the lives of many people in jeopardy. Often the objectives are not clear (save the people in the building or quickly put out the fire?), the information is uncertain (the firefighter does not have a clear idea of the building’s floor plan or of the material contained in the building) and the intervention procedures are not always codified (one needs to use one’s imagination in order to find a way to free a wounded person from inside a vehicle after an accident). Experts of all fields make decisions by quickly refer- ring to well-known situations and past experience. In particular, they promptly identify the objectives to be pursued, the most important cues to observe and monitor, the possible situational developments and the plans of action to be followed. In other words, the assessment of the efficiency of a selected course of action (or, better yet, of one automatically recalled by memory) does not come about through a comparison with other actions, but by directly discovering a plausible, and therefore satisfac- tory, solution. The decision making models based on recogni- tion (Klein, 1998) are inspired by counter-intuitive observation. Experts make decisions without analytically assessing the pros and cons of each option: beginners or individuals without ex- perience are in fact the ones who make decisions on an analyti- cal-comparative basis. However, individual differences in decision making behav- iour are not only related to the decision maker’s level of exper- tise, but also to other variables such as cognitive and motiva- tional styles, age, sex, socio-economic status and still others. Some authors, for example, have hypothesized the existence of veritable decision making styles (Scott & Bruce, 1995), which define styles of individual reaction within given contexts. Now, if it is true that decision making styles exist whereby individu- als use some with more frequency than others, it is just as true that these styles are not rigid and unchangeable (Glaser & We- ber, 2005), but rather flexible and modifiable in response to specific situations (Driver, Brousseau, & Hunsaker, 1990). Numerous decision making styles have been identified and described. The simplest ones follow the model of a sort of bi- polarity corresponding to specific decision making styles. The deliberative-intuitive dimension (Epstein et al. 1996) is an ex- ample of this. This dimension distinguishes between individu- als who usually decide in an analytical and reflective manner and others who, instead, decide in a quick and intuitive way. Other typologies of more detailed decision making styles in- stead describe multiple dimensions. Scott and Bruce (1995) identify five different decision making styles: • The rational style: characterized by a complete search for information, by the consideration of the possible alterna- tives and by the assessment of their consequences; • The intuitive style: based on the attention to global as- pects more than to the systematic processing of informa- tion and, in addition, on the tendency to decide on the ba- sis of intuition and feelings; • The dependent style: typical of people who prefer to re- ceive suggestions before making any choice at all; • The evasive style: typical of individuals who tend to put off or avoid decisions; • The spontaneous style: characterized by the propensity to decide as fast as possible. In order to measure these decision making styles, Scott and Bruce developed the General Decision Making Style Inventory (GDMS) for defining individual decisional profiles. A different approach to distinguishing between the diverse ways of deci- sion making was proposed by Schwartz and his group (2002) and includes, rather than the identification of a specific decision making style, the tendency of an individual to look for the best possible result (the “optimizer”) or to settle for a sufficiently good alternative (the “satisficer”). The Maximization Scale (Schwartz et al., 2002) is a tool for distinguishing those who, always looking for the best option, tend to base their own deci- sions on the comparison with others, and then prove to be un- satisfied with the choice made; from those who, instead, in settling for an option which is good enough, and therefore not  M. MALDONATO ET AL. 815 necessarily the best, show a fair level of satisfaction with re- spect to their decision. It must also be said that more than a century ago James had already outlined a profile of the decision making types. The first may be called the reasonable type. It is that of those cases in which the arguments for and against a given course seem gradually and almost insensibly to settle themselves in the mind and to end by leaving a clear balance in favor of one al- ternative, which alternative we then adopt without effort or constraint [...]. A “reasonable” character is one who has a store of stable and worthy ends, and who does not decide about an action till he has calmly ascertained whether it be ministerial or detrimental to any one of these [...]. In the second type of case our feeling is to a certain extent that of letting ourselves drift with a certain indifferent acquiescence in a direction acciden- tally determined from without, with the conviction that, after all, we might as well stand by this course as by the other, and that things are in any event sure to turn out sufficiently right. In the third type the determination seems equally accidental, but it comes from within, and not from without [...]. There is a fourth form of decision, which often ends deliberation as suddenly as the third form does. It comes when, in consequence of some outer experience or some inexplicable inward change, we sud- denly pass from the easy and careless to the sober and strenu- ous mood, or possibly the other way [...]. All those “changes of heart”, “awakenings of conscience”, etc., which make new men of so many of us, may be classed under this head [...]. In the fifth and final type of decision, the feeling that the evidence is all in, and that reason has balanced the books, may be either present or absent. But in either case we feel, in deciding, as if we ourselves by our own wilful act inclined the beam: in the former case by adding our living effort to the weight of the logical reason which, taken alone, seems powerless to make the act discharge; in the latter by a kind of creative contribution of something instead of a reason which does a reason’s work (James, 1950, pp. 796-798). Empirical and theoretical research developed within the do- main of the psychology of decision making suggests that cogni- tive strategies follow paths that are often different from those postulated by economic rational choice. According to the model of the adaptive decision maker developed by Payne, Bettman and Johnson (1993), the decision making process is a highly contingent form of processing information with which indi- viduals use adaptive decision making strategies and heuristics in response to their limited capacity for processing information as well as to the complexity of decisional tasks. A decision making strategy is a sequence of conative and cognitive mental operations (actions on the environment) used in order to trans- form the state of initial knowledge into final knowledge in which the decision maker considers the decisional problem to be resolved. Cognitive strategies are selected in relation to a series of factors: the way in which the information in presented, the complexity of the problem, the decision making context and the characteristics of the decision maker (Hastie & Dawes, 2001). Such variables, regardless of the values of the alterna- tives, influence the selection of the strategies by modifying the cognitive effort necessary for implementing them (Bettman, 1993). Everyday experience shows that, when facing various situa- tions, we make decisions in a non-stereotypical way. A funda- mental characteristic of our cognitive system is in fact the ex- traordinary flexibility of the decision making strategies at our disposal. First of all, when “deciding how to decide”, individu- als consider accuracy and cognitive effort not as absolute at- tributes connected to a strategy, but rather as properties de- pendent on a specific situation. Such an assessment―estab- lished either beforehand (top-down style) or during the accom- plishment of the task (bottom-up style) and the processing of the decision itself―can influence the choice of the various decision making strategies at one’s disposal. The strategy cho- sen will be the one that allows the decision maker to make a good decision with the least possible effort. The most frequent simplification strategies (Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993) are commonly classified as compensatory and non compensatory. Compensatory strategies require a quantitative judgement and are applied when the options or the attributes which describe the various decisional alternatives are commensurable on the basis of their attractiveness/utility values. In other words, an individual chooses the alternative having an attribute that com- pensates for the sacrifice that she is willing to make by re- nouncing the consideration of other appreciable attributes. Non compensatory strategies, instead, are used for those de- cision making problems in which options and criteria are inc- ommensurable and the limited attractiveness of an option in relation to a certain criterion cannot be compensated by the greater attractiveness of the same option in relation to another criterion. Individuals often have to mediate between accuracy and effort in the selection of a strategy according to the re- quirements of the task: in such cases a certain flexibility is nec- essary in the use of the strategies to be adopted. The decision making process, considered as a limited capacity cognitive activity, in fact aims at satisfying several objectives, such as for example minimizing emotional strain due to the presence of conflictual values among alternatives (Hogart, 1987), reaching socially acceptable and justifiable decisions, and making accu- rate decisions which maximize advantages and minimize the cognitive effort required for acquiring and processing informa- tion (Simon, 1978). Minimizing cognitive effort is defined on the basis of the amount of time and the type of mental operation required for putting a certain decision making strategy into action. Zipf (1949) proposes the principal of minimal cognitive effort, according to which a strategy is chosen that ensures the minimum effort in the reaching of a specific desired result. The strategies that involve more accurate choices are often those that entail more effort and this indicates how the choice of strategies is the result of a compromise between the desire to make the most correct decision and the desire to use the small- est amount of effort (Johnson & Payne, 1985). Conclusions In the next few years, and with the ever more accurate con- tribution of the cognitive neurosciences, we could have further elements to reflect upon in this difficult field. However, we can certainly already affirm that without high performance decision making devices like those studied in the paradigm of Naturalis- tic Decision Making the building of civilization, and perhaps even the evolution of the species, would have been impossible. Perhaps it is not paradoxical to think that decision making de- vices developed starting from the cognitive limitations of hu- man beings, revealing themselves to be flexible when faced with unexpected situations and, above all, ecological in the use of the environment’s resources. In this sense, if it is true that the human mind has accumulated information and knowledge by means of a significant quantity of rational decisions, the vast majority of these decisions have been supported by a natural logic whose rules have proved themselves to be advantageous in an evolutionary sense. References Bernoulli, D. (1738). Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis. Com-  M. MALDONATO ET AL. 816 mentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae, 5, 175- 192. Bettman, J. R. (1993). ACR fellow’s award speech: The decision maker who came in from the cold. In L. McAlister and M. Rothschild (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (pp. 7-11). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research. Driver, M. J., Brousseau, K. R., & Hunsaker, P. L. (1990). The dynamic decision maker. New York: Harper and Row Publishers. Epstein, S., Pacini, R., Denes-Raj, V., & Heiner H. (1996). Individual difference in intuitive-experiential and analytical-rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality and S ocial Psychology, 71, 390-405. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.390 Friedman, M. (1953). The methodology of positive economics. In M. Friedman (Ed.), Essays in positive economics (pp. 2-43). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Gigerenzer, G. (1997). Bounded rationality: Models of fast and frugal inference. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for Human Development. Gigerenzer, G. (2001). The adaptive toolbox. In G. Gigerenzer and R. Selten (Eds.), Bounded rationality: The adaptive toolbox (pp. 37-50). Cambridge: MIT Press. Gigerenzer, G. (2007). Gut feelings: The intelligence of the uncon- scious. New York: Penguin Books. Gigerenzer, G. & Goldstein, D. G. (1996). Reasoning the fast and fru- gal way: Models of bounded rationality. Psychological Review, 103, 650-669. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.4.650 Glaser, M. & Weber, M. (2005). Overconfidence and trading volume. C.E.P.R. Discussion Paper, 3941. London: C.E.P.R. Hamilton, D. L. & Gifford, R. K. (1976). Illusory correlation in inter- personal perception: A cognitive bases of stereotypic judgments. Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, 12, 136-149. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(76)80006-6 Hastie, R. & Dawes, R. M. (2001). Rational choice in an uncertain world: The psychology of judgment and decision making. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Hey, J. D. (1979). Uncertainty in microeconomics. Oxford: Martin Roberson. Hogart, R. M. (1987). Judgement and choice: The psychology of deci- sion. New York: Wiley. James, W. (1950). The principles of psychology. New York: Dover Publications. Johnson, E. J. & Payne, J. W. (1985). Effort and accuracy in choice. Management Science, 31 , 394-414. doi:10.1287/mnsc.31.4.395 Kahneman, D. & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited: Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 103-119). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment under un- certainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kasparov, G. (2007). How life imitates chess. New York: Bloomsbury USA. Klein, G. A. (1993). Recognition-primed decisions. In W. B Rouse (Ed.), Advances in man-machine systems research (pp. 47-92). Greenwich: JAI Press. Klein, G. A. (1998). Sources of power: How people make decisions. Cambridge: MIT Press. Klein, G. A. & Calderwood, R. (1991). Decision model: Some lessons from the field. IEEE Transactions on Systems Man and Cybernetics, 21, 1018-1026. doi:10.1109/21.120054 Lipshitz, R., Klein, G., Orasanu, J., & Salas E. (2001). Taking stock of naturalistic decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 14, 331-352. doi:10.1002/bdm.381 March, J. (1994). A primer decision making. How decision happen. New York: The Free Press. Marschak, J. & Radner, R. (1972). Economic theory of teams. New Haven: Yale University Press. Mullainathan, S. & Thaler, R. H. (2000). Behavioral economics. Cam- bridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Work- ing Paper 7948. Neumann, J. von & Morgenstern, O. (1947). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Nisbett, R. E. & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of soci a l j u d gm e n t . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Richardson, R. C. (1998). Heuristics and satisficing. In W. Bechtel and G. Graham (Eds.), A companion to cognitive science (pp. 566-575). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. Schwarz, N. & Vaughn, L. A. (2002) The availability heuristic revisited: Recalled content and ease of recall as information. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), The psychology of intuitive judgment: Heuristics and biases (pp. 103-119). Cambridge: Cambridge Univer- sity Press. Scott, S. G. & Bruce, R. A. (1995). Decision making style: The devel- opment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Meas- urement, 55, 818-831. doi:10.1177/0013164495055005017 Selten, R. (1998) Aspiration adaptation theory. Journal of Mathemati- cal Psychology, 42, 191-214. doi:10.1006/jmps.1997.1205 Simon, H. A. (1983). Reason in human affairs. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Simon, H. A. (1997). Models of bounded rationality. Boston: MIT Press. Simon, H. A. (2000). Scienza economica e comportamento umano. Torino: Edizioni di Comunità. Simon, H. A. (1979). Rational decision making in business organization. Nobel Lecture, Stocholm 1978. American Economic Review, 69, 493-512. Simon, H. A. (1978). Information-processing theory of human problem solving. In W. K. Estes (Ed.), Handbook of learning and cognitive processes (pp. 271-295). New York, Hillsdale: Erlbaum. Stanovich, K. E. (1999). Who is rational? Studies of individual differ- ences in reasoning. Hillsdale: Erlbaum. Stigler, G. (1961). The economics of information. Journal of Political Economy, 69, 213-225. doi:10.1086/258464 Tietz, R. (1992). Semi-normative theories based on bounded rationality. Journal of Economic Psychology, 13, 297-314. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(92)90035-6 Todd, P. M. & Gigerenzer, G. (2000). Précis of simple heuristics that make us smart. Behavioral an d Brain Sciences, 23, 727-780. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00003447 Zipf, G. K. (1949). Human behavior and the principle of least effort. Cambridge: Addison Wesley Press.

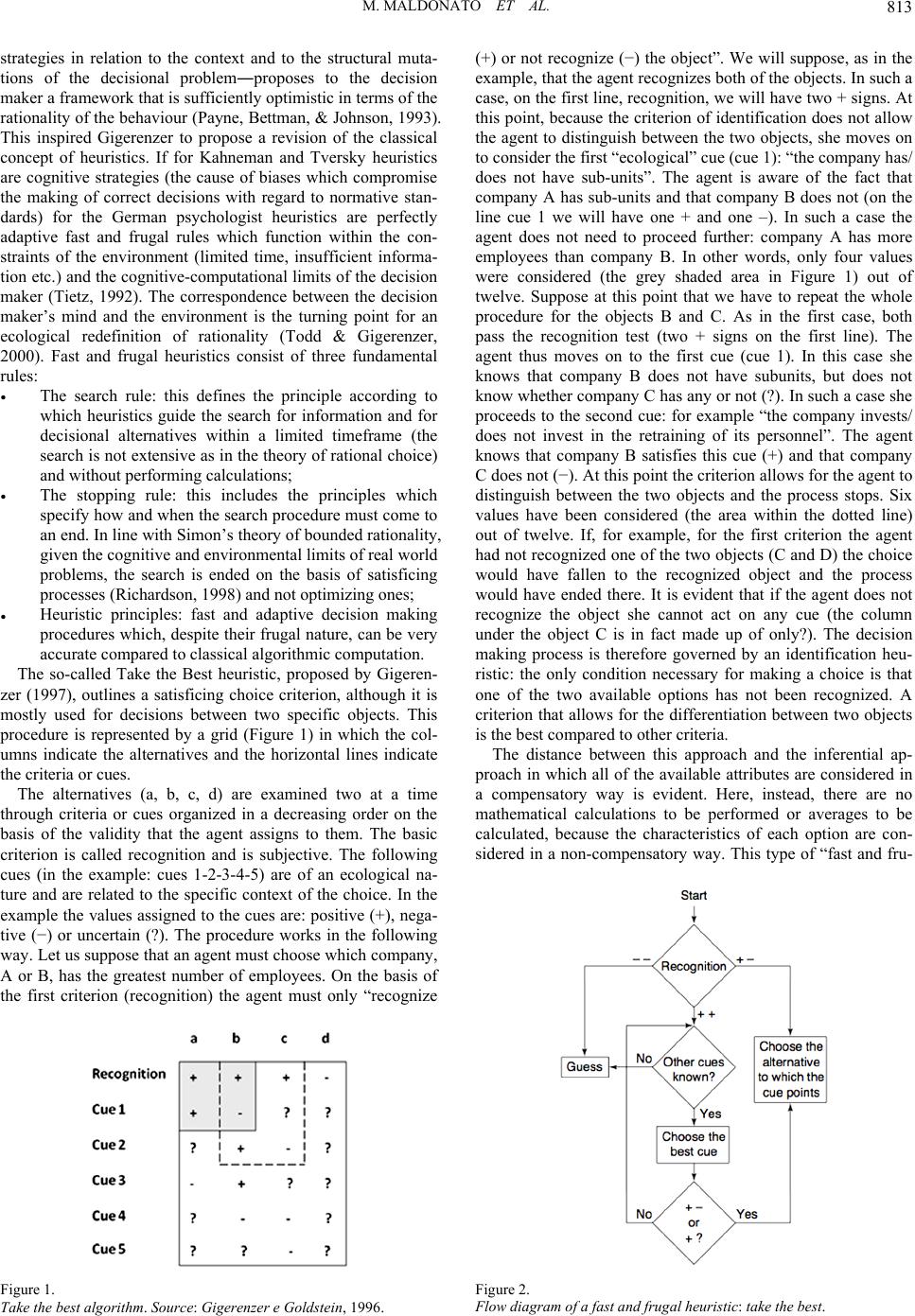

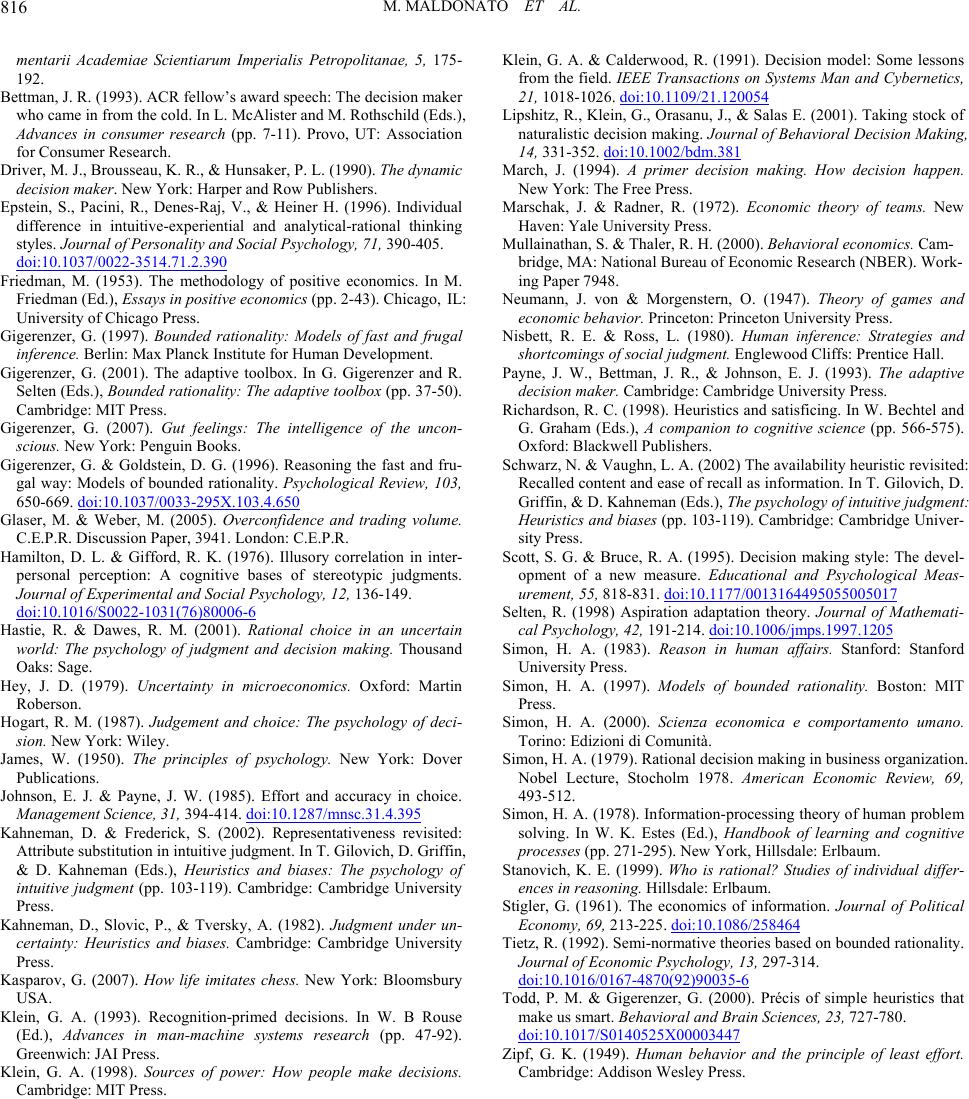

|