Education to Theatricality and the Human Relationship: The Creative Movement ()

1. Introduction

To discuss the relationship between the creative movement and the human relationship, it is necessary to contextualize the field of study in which education for theatricality is born. Secondly, briefly present the findings on mirror neurons and to analyze the implications of neuroscience studies in knowing that today we have communication between people; finally, to evaluate the contribution that the theatrical education laboratory may have in the formation of the person.

The Education to Theatricality is a young science that studies the relationship between Theatre (expressive arts: acting, literature, music, dance, painting and sculpture, video, etc.) and Education (Oliva, 2017). First of all, it explores the most historic aspects of theater pedagogy (Oliva, 2007; Oliva, 2009; Miglionico, 2009; Pilotto & Viola, 2006; Pilotto & Viola, 2009). Secondly, it compares the relationship between expressive arts and pedagogy particularly in the school world (Di Rago, 2001; Perissinotto, 2001; Pilotto, 2006; Di Rago, 2008; Salati & Zappa, 2011); finally, it studies and elaborates didactic and laboratorial methodologies concerning the different languages of performativity in an educational and formative function (Oliva, 1999; Oliva, 2010; Oliva & Pilotto, 2013; Salati & Zappa, 2014; Tonolini, 2015; Tonolini, 2019).

As regards the aspect concerning mirror neurons (Stamenov & Gallese, 2002; Rizzolati & Sinigaglia, 2006; Gallese, 2010; Ammaniti & Gallese, 2014; Rizzolati & Sinigaglia, 2019), it means to place itself in the domain of neuroesthetics. Recent scientific developments on connections between biology, neurobiology and cognition offer new ways to understand different elements of human activities, including imagination, emotion, empathy, memory, physicality and reason. Starting from these studies, new literature is being developed that begins to reflect the relationship between theatrical expressiveness and neuroscience (Blair, 2008; Sofia, 2009; Falletti & Sofia, 2011; Falletti & Sofia, 2012).

Attention to the application of neuroscientific knowledge on the actor, at the same time, it is reciprocated from the point of view of the neuroscientists who use the actors for their studies (Sofia, 2013).

Mirror neurons, according to the neurophysiologist Vittorio Gallese, would correspond to the neurophysiological correlate Empathy; the study of the neural dimension of intersubjectivity offers points of reflection for a naturalization of the theatrical action first thinking of the actor as a body in relationship. In everyday life, we literally make our dispositions our own corporal others, Education to Theatricality, in particular with the Creative Movement, investigates the creativity of everyday life that becomes an art.

The neurosciences contribute to the theater allow to better define the starting point of mutual recognition, innate, categorical, pre-cultural. Thanks to these studies, succeeding in understanding how to build the mirroring mechanism between mind and mind in the real presence of bodies, it is possible to think of expressiveness training not only as an artistic practice but as a real tool to educate to the relationship.

In the elaboration of the laboratory as a relational training of the person the body in movement, the excited body becomes the point of research in Education to Theatricality. It is a question of re-evaluation evaluating the practice and the theory of the performative act by analyzing the relationship physiological between body action and emotional experience; and between these two and communication. The Creative Movement (Oliva, 2014; Oliva, 2015a; Oliva 2018) stands as a laboratory practice that tries to put together all these dynamics (the person’s relationship with himself and his body; self-awareness and narration of identity, development of creativity, relational communication with others).

2. Education to Theatricality

Education to Theatricality was born as a consequential theory to the artistic and pedagogical theories of the twentieth century, and of its most important goal is to promote the psycho-physical and social well-being of the person. It is a means and not a goal of the personal growth and of personal changes; theatricality and art in general, thus conceived, assume the role of “vehicles” for self-knowledge. Education to Theatricality is a science that includes different disciplines such as pedagogy, sociology, human sciences, psychology and the performing arts in general. The scientific basis of this discipline allows us to apply it in all possible contexts possible and with any individual, because it keeps the man as he is in the center of its pedagogical process. One of the fundamental principles of Education to Theatricality is the construction of the actor-person; the main aim is the development of creativity and imagination through a scientific training leads by the actor on himself (Oliva, 2015b: p. 87).

The Education to Theatricality or the science that studies the relationship between Theatre and Education (Oliva, 2015c: pp. 46-60) rooted in the innovations that directors-pedagogues of the twentieth century (Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, Vakhtangov, Copeau, Chancarel, Brecht, Grotowski, Brook, Boal, Barba), have made in the field of theater and interwoven in its educational purpose, with the theories of the greatest educators of the past two centuries (Dewey, Montassori, Freinet, Maritain, etc.).

Education to Theatricality, which finds its psycho-pedagogical basis in the concept of Art as a vehicle defined by Grotowski (Oliva, 2015c: p. 26), is education for creativity and it represents a precious opportunity for anyone to affirm their identity, claiming the value of the expressive arts as a vehicle for overcoming the differences and as an actual element of integration Through art, man can tell something about himself, and he is the protagonist of this creation. It puts him in touch with himself, but, at the same time, it creates a connection with the space in a temporal dimension. The Education to Theatricality is a vehicle of growth, of individual development, of self-assertion and of acquisition of new personal skills. The expressive arts do not present models, in fact, every man should be each his own model. So, the identity of every person creates a relation through a telling reality; action, word and gesture become instruments of investigation of life. Performance art becomes a vehicle for self-knowledge, for the manifestation of his own creativity.

Art as a vehicle “generates” the idea of a person-actor defined performer, an actual man of action, because he is dancer, musician, actor, total man, which performs a performance, giving completely his personality to the audience. His action does not coy a cliché, it is not a precise and defined action that takes place only and exclusively in the physical completeness and perfection. The actions are modeled in relation to the personality of the ego that acts; each of them is intimate and subjective. For this reason, Education to Theatricality, and the laboratory, in an experience that everyone can live, even if we talk about disability or diversity.

In conclusion, the theater in Education to Theatricality should not be considered an end in itself, but must give birth to an activity that has an educational purpose of human formation and orientation: supporting the person in the realization of their individuality and the rediscovery of the need to express themselves beyond the stereotyped forms, unconditionally believing in the potential of every individual. Trains individuals to face, in a more confidently way, the real, it helps them to understand the hard social reality in which they live and supports them in their work for growth. Theater can help you rediscover the pleasure of acting and experiencing different forms of communication, encouraging an integrated growth of all levels of the personality.

3. Pre-Expressivity

Every person has to communicate, but not every person is always aware of his expressive status (Oliva, 2015b: p. 91). The Creative Action is linked to daily action; to develop the first it is essential to: a) increase the capacity for attention, intentionality and management of the body that are not normally exercised; b) Reappropriate oneself in one’s natural pre-expressiveness. Much of what is used to communicate is developed in the person form education, from culture, from the family context and social rules. It can be said that communication is fundamentally sociological.

Education to Theatricality starts with the idea that each subject has its own natural pre-expressivity that characterizes him in a particular way, even if he is not aware of this. Becoming aware means to discover our Ego and this implies the desire and intention to get deeply involved. “The concept of pre-expressivity, then, is useful because it is thought in relation to the actor, who is a person who uses an extra-daily technique for his body, in a situation of organized representation; it is linked to the single human being and accompanies it throughout its path, taking different shapes and changing with it. In this sense, it is not correct to refer to man and pre-expressivity as two distinct realities: the two terms are mutually interwoven” (Oliva, 2005: p. 235).

The human being does not fully reveal itself if it does not discover and enhance its pre-expressivity. Development of imagination and of creativity is, therefore, the main goal to achieve to enhance the personal qualities of the involved subjects. This aim can be reached by following the synthetic formula: “pre-expressivity + methodology = development of individual creativity” (Oliva, 1999: p. 89).

In this formula, the word methodology contained also the expertise to create improvisations. “This instrument has an educational purpose even before than a theatrical one, because it has a huge introspective strength. It is able to let emerge countless personal elements (emotions, memories, insights, feelings) otherwise hidden and submerged but that influence personality and the action of the subject” (Oliva, 2015b: p. 91).

4. The Laboratory

The laboratory is the methodology through which people rediscover their daily expressive capacity and learn to make it creative. The body movement from simple and spontaneous becomes intentionally communicative and artistic without losing its naturalness.

The laboratory of expressive arts is “the educational, pedagogical and creative place where the person’s growth process and the individual creativity develop. It is a physical and mental space for experimentation and research, conducted according to a precise psycho-pedagogical methodology” (Oliva, 2018: p. 95).

A fundamental aspect of the laboratory of Education to Theatricality is the personal relationship between the participants; a similar relationship should exist between actors and spectators during the creative project that concludes the laboratory itself. The openness to the other is a feature that deeply belongs to man; it is not just a simple exchange of communication, but an experience of affective participation and reciprocity. However, the desire to encounter the other should be real and authentic: this implies that everyone accepts others as they are. The laboratory, therefore, is an opportunity to grow, to learn by doing, with the belief that the most important thing is the process and not the product: the performance (or creative project) is just the conclusion of a training program. The theatrical activity stimulates the need for an interpersonal knowledge that leads to a relationship in which others are recognized in their dignity. The laboratory offers the opportunity to understand that it is possible to change certain situations and to change ourselves. The laboratory of Education to Theatricality has a great pedagogical value and offers an important contribution to the educational process, because, thanks to the personal training, everyone can learn to express what it is “screaming” inside, to understand and control our energy, to accept what at first was suppressed or repressed. We should not forget that personality of man depends on the quality of his experiences, which characterize his way of relating or not relating, that is his lifestyle. Theater and in particular the laboratory, allows to make new experiences and to experiment different and unusual life situations, which can contribute to redefine the Ego but even the world and the others. Theater means also see again our past: re-experience fears, relive certain behavior—or situations, not to remove them, but to realize that now we are stronger and we can recognize our positivity (Oliva, 2015b: p. 90).

The workshop of expressive arts is a path of rediscovery, a sort of “re-education to one’s own presence (doing, to be able to do, to be able to be); it is a pace where learning to live in a human and social way, where the individual can develop a free, democratic and critical mindset about himself and the reality that surrounds him, learning to exercise his own capacity for choice, dialectics and of responsibility” (Oliva, 2018: p. 97).

In the Education to Theatricality, the workshop develops along three dimensions. First of all, “the workshop experience is a psycho-physical action that involves both body and voice of the actor-person. Gestures, shape and movement express or hide interior resonances. Voice and words are inside this corporality. In fact, the voice confirms, clarifies, underlines or denies the truth of the positions of the body; at the same time there is also the inverse relation: the body gives strength or weakens the truth of the words” (Oliva, 2018: p. 97).

A second dimension is creativity. By definition, “the workshop is the place where the actor-person can and must free his imagination. This is not always possible in everyday life, but here the person develops his own energy and condenses it into new creations that open up new horizons to his knowledge” (Oliva, 2018: p. 98).

Finally, the social dimension intertwines with these two elements. “The body is always related to what surrounds it: other bodies, objects, environment and so on. Thus the experience of the actor-person is modulated in a relationship based on conflict. Living the workshop determine some different dynamics respect to everyday life, that highlight the pedagogical value of this experience” (Oliva, 2018: p. 98).

The first dynamic is suspension. In the workshop, the daily experience is temporarily suspended and there is a new dimension of life which is protected by the conditioning and judgments in which every person is normally immersed. This condition is valuable because it allows the establishment of a deep trust: the optimal environment for every process and for educational relationships. The dynamics of the suspension enables the subjects involved to explore themselves, the situations, the personal and the social resources.

The step of exploration is preliminary to what can be defined as the dynamic of “construction”. The workshop can, in fact, lead every actor-person or the whole group to recognize a new form of personal behavior, of psychic interiority or of social behavior that has been created by the theatrical work and that becomes the educational heritage of the group. This novelty expresses a concrete possibility of change that every educational process must bring out.

So we can state that the laboratory experience is modulated on three mutually interwoven levels (Oliva, 2015c: p. 96).

- The individual level: the actor-person puts into play the specific skills to be able to stay on the scene or to hold a confrontation with an audience, through the means of contact with himself that, in theater, consists of the dramatic monologue; he must then make use of these skills in everyday life, getting a greater fulfillment from both himself and others.

- Relational level: at this stage, the individual is experienced in the dialogue, or in the psycho-physical relationship with the partner on the scene. Trying to establish emotional contact with the partner, it is necessary to develop further human faculties, such as the precision and control of one’s self.

- Group level: at this late stage the individual is experienced in and with the group.

In a process of this type, the conductor of the laboratory is of fundamental importance, and consequently its formation and the design capacity. The educator to theatricality so defined must be an actor-educator, searching with this term to interweave two fundamental dimensions: one is the professional theater that stimulates and brings to light the artistic abilities of the students and on the other hand the specific educational skills of the educator.

Another important aspect of the workshop of Education to Theatricality is linked to its role in learning (Oliva, 2018: p. 100). In fact, there are some elements that are directly involved when a person participate to an artistic-educational process: “the affective value, the evaluation of the action in relation to a purpose and, finally, the possibility of having a proof of knowledge concerning reality” (Oliva, 2017: p. 156).

The expressive arts workshop needs a text, a context and an adult of reference (the educator). For the participant, the “performative action is the opportunity to do, to seek, to discover and to realize; for the educator, it is the tool by which building the learning process” (Oliva, 2018: p. 100).

The evaluation of the action in relation to a goal is the second element. The performative action has an evident purpose: “proceeding with the realization it becomes clear and undergoes some changes respect to the beginning idea” (Oliva, 2018: p. 100). It is important that everyone can start his own creative experience with a personal idea of what is the goal of the action, so he can self-evaluate his ability to achieve the purpose in his process of goal-ideation-realization of the action. This process is linked to a context that provides both individual and collective purposes.

The third element concerns “the possibility of having a sort of evidence of the knowledge concerning reality (Oliva, 2018: p. 100). The performative action is progressively known and is the result of the encounter and the interweaving of the individual actions. “Each one is at the same time an actor and a spectator of his actions. So every subject, in the artistic action, can have much more chances to know himself and others. A person does not just act in every but learns to act and to observe. The workshop becomes a place for knowledge and learning” (Oliva, 2018: p. 101).

5. Languages and Communication

Artistic communication takes place through the use of languages: “Language is certainly the most powerful and effective communication system, the most typically and universally recognized as unique to man. The essential aspect is to be a communication system inserted in a social situation, so it is not only a cognitive process but also a symbolic behavior” (Oliva, 2015d: p. 121), essential and genuinely social activity. Every communication not only transmits information, ideas, stories, thoughts, emotions, but involves a complex game of references, readings and interpretative adjustments. So every communication imposes a behavior and defines a relationship (Watzlawick & Beavin, 1971: p. 43).

The languages of theatrical communication are verbal language, nonverbal language, the language of space and the language of writing.

It is fundamental to reaffirm the role of corporeity in communication and in the relationship for which the not-verbal language has different and important functions in human social behavior. “The body is a communicative language that expresses feelings, emotions and messages. It can be considered the primary language in the development of interpersonal relationships. In fact, the subject through the body language, transmits the image of himself and his body and participates in the presentation of himself to others; it supports and completes the verbal language and has a meta-communicative function. It provides elements to understand the meaning of verbal expressions and replaces the word when we cannot speak” (Oliva, 2018: pp. 101-102).

Every person, from the moment of his birth, uses consciously the forms and the bodily signs, when he begins to realize that the other is a different human being; in this way, he begins to establish his relations with reality and to build interpersonal relationships. Moreover, the body language is a channel of communication which is always open, in fact, in a verbal relationship you can do not speak but your body never keeps silent.

In fact, first of all, a man learns to move, then to stutter, then to think. It is precisely because of this order of development that awareness in the use of the body is a necessary condition to be adequately prepared to meet other languages and to be able to use them consciously.

A workshop of Education to Theatricality “helps the subject to become conscious, because it proposes a constant experimentation, discover and conscious use of the body that leads to discover and use it in unusual ways. So the subject can produce unexpected and new forms of expression” (Oliva, 2018: p. 2 ).

These new expressive forms renew the language but also allow the subject to become a skilled reader of the communication of others (ability to grasp the elements of the grammar used, perception of transmitted sensations, intentions, emotions, etc.).

6. The Creative Subject and the Creative Movement

In the researches of Education to Theatricality is being defined in terms of strictly scientific the process that leads to the development of a creative act (Oliva, 2015c: pp. 32-35). The creative subject is, in effect, the subject of an interdisciplinary debate: on one hand, creativity is the focus of interest of psychologists and neuroscientists (Mente & Cervello, 2011: p. 83) that are trying to identify the subjective characteristics and mental processes that determine its development, on the other hand, is getting stronger the reflection on these issues in both the artistic, expressive and the psycho-pedagogical way (Cesa-Bianchi & Antonietti, 2003).

The creative man is, in truth, a category of the contemporary thought that takes shape only in the second half of the twentieth century. In the theater field, between the nineteenth and twentieth century, with the birth of the pedagogues-directors, develops the concept of creative actor and you start talking about actor as a man who consciously uses himself to express himself.

Only from the cultural revolution founded by the figure of Jerzy Grotowski in 1960 with the development of the concepts of art as a vehicle and of performer you start talking of creative man that uses art, or rather the arts and expressive languages, as a vehicle to consciously work on itself (Slowiak & Cuesta, 2007). Beyond the distinction of artistic genres, Grotowski redefines the idea of art as a field of research on the essence of man. Creativity, therefore, stops to be the preserve of only the artists or the genius and becomes characteristic of the human person as such; the thesis is also supported by the affirmation of neuroscience that affirms that each person has a creative potential to develop. Art represents a great opportunity for developing this potential. Precisely for this reason, in the view of the Education to Theatricality, the focus is on the creative subject: the theater workshop becomes a method of work that is based not only on the intention to transmit knowledge, but, above all, on forming the subject through practical experience and the discovery that it follows (Oliva, 2005: p. 23). Through sensorial incentives, through the act, in motion, the subject experiences in practice (learning by doing) and learns or enhances both the cognitive and conative factors that modulate the expression of creativity. The first will determine by the ability to develop different and multiple answers in a same situation-incentive-question (divergent thinking) or the ability to consider a problem from different points of view (mental flexibility); the latter will determine the development of certain personality traits such as openness to new experiences, the willingness to expose themselves to the risk of making a mistake, the attitude to the fascination for the unknown and the constancy in doubt, the ability to resist the dominant currents of thought and motivation, that is the pleasure of dedicating to the creative activity.

Talking about creative action in the field of expressivity means to introduce another concept, the one of “Creative movement”. Creativity that becomes action—that is action—is linked, first, to the body and motion. The creative movement represents the development of continuous creative acts which occur in time and space and leads to a simple but fundamental anthropological concept: the relationship between the human being and the motion. The man in his existence moves, the immobility is impossible for him. The motion is a specific element of life and plays a central role in the relationship with oneself and with others.

The motion does not come only from a material need or by an act of will, it is also emotion. Precisely for this reason, the creative movement borns from both the subject’s relationship with the world of creation through the expressive arts and from the wide-ranging analysis of the man and of his existence, that connects the man and the body, between body and expression, between body-motion and creativity. The discipline is concerned, then, to know the body in full and of the preparation of this as an expression tool. It is important, in effect, not only to become aware of the various joints of the human structure and their use in creating rhythmic, gestural and spatial patterns, but also the state of mind and the inner attitude that influence and determine each other in relation to the body actions. Science Education to Theatricality, in the study of the creative act and its realization in “creative movement”, is set up as a human science that determines its practices from a specific conception of man and his existence. In particular, it refers to the delsartiana conception for which man is an indissoluble unity of three distinct elements—body, soul and intellect—interdependent and always in a close interaction contact. Interesting, though, is to note how, regardless a particular philosophical conception, theories of this science show their independent effectiveness: by starting the physical theory from the action (from the motion), Education to Theatricality inevitably takes into consideration and verifies the neurological and physiological processes that govern the sphere of the human body. A peculiarrity of this science is, in effect, that he had collected the practice of theater pedagogues-directors of history and systematizing their axioms, have been able to extract from them a universal knowledge. Creativity, as the ability to transform, build and produce, is expressed in the creative act, or in an action that underlies the development of a process and a specific state of being. Creativity refers to a productive activity which, however, does not only declines in originality (the invention of new ideas or expressions), but also in the revision of existing elements. The subject, through creativity, transforms external incentives composing them in a unique and new way because personal; in a study on the subject is reported that, “[...] the creative act [...] is always caused by the encounter between an incentive from the outside and its own state of consciousness. Through creativity the subject faces in a personal way the stresses from the environment and adapts to it modifying it according to his needs. Creativity requires a constructive way of facing the reality and the ability to accommodate the experience and then break the rules by intervening on reality. The way to create refers to the production capacity, an activity that creates out of nothing, but also [...] to an elaboration of the original elements that already exist, to confer the character of novelty and uniqueness; with creativity are retrieved into memory the various experiences accumulated, combined and used in a manner consistent to the situation” (Oliva, 1999: p. 29). Within the expressive creative act is outlined as an action that involves the totality of the human being. To get to have a creative act are stimulated and used all the elements of the “trinity of the person”: the intellect in its dimension of mind (fantasy and imagination); the soul in its dimension of emotion and feeling; the body in its dimension of gesture and movement, body identity and shape.

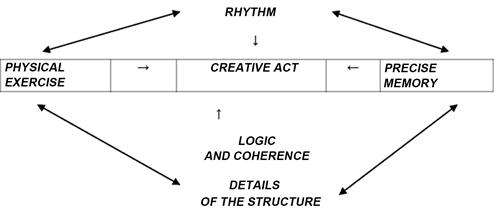

Below is the chart that summarizes the theory of the creative act (Oliva, 2015e: p. 93): physical action through body language + rhythm + emotional memory (precise memory) together they carry out a structured action with logic and coherence.

Here is the chart that summarizes the theory of the creative act: Figure 1 (Source: Oliva, 2005: p. 310).

From the research of Grotowski, the work of theoretical and practical study of Education to Theatricality, as stated in the above scheme, has described the creative process as the related set of a number of elements: a) exercise as a starting point (the body of the performance); b) the development of this through a work of logic and consistency that determine a detailed structure; c) this process is determined, in addition, in a rhythm or tempo-rhythm that governs the action developing it in time and space; d) the necessary presence of a memory of life, that is an emotional condition precise. As scientists and neuroscientists emphasize there is no creativity that is not connected in the making and in the seeing of an emotional affair. You can see that in the memory, physical exercise and in the logical structure of the creative act are involved respectively the soul, the body and the intellect of the person.

Its complexity, the richness and the whole of the creative act are a fundamental point of any expression path linked to the artistic languages; especially if this activity is inserted into pedagogical and training path. If, in effect, the educational workshop is, as defined by Cesare Scurati, that place where “you can face new routes of exploration, [that allow] to create ways of interaction [...] based on the quality of the accompaniment, on the closeness, on the support and reciprocity and where is enhanced the productivity of everyone” (Salat & Zappa, 2011: p. 2), the creative act becomes necessary and indispensable. Without the development of the self-production is not possible, in effect, a real process of growth and development of the person, but without this, or without putting at stake the whole person, is not possible even the development of a creative action. The deepest experience that an actor-person can do is, therefore, the production of a creative act. It contains the synthesis and the apex of the theatrical and pedagogical Cultural Revolution that hit the man in the twentieth century: the perception that man has of himself as a “man in the middle” able to change the nature and the events, able to live his time and social changes, subject and protagonist of his life and its implementation.

Education in Theatricality, in the study of the creative act and of its concretization in the “creative movement”, is configured as a human discipline that communicates through its praxis to a precise conception of man and his existence. The practice of creative movement can be a useful tool to increase and affect a person’s cognitive and learning abilities.

7. The Laboratory of Expressive Arts as Workshop of Emotions

The relationship between body, creativity, movement and expression revolves around the emotional sphere. The expressive arts workshop, then, is also a laboratory of emotions (Oliva, 2015b: p. 91).

The experience of feeling emotions is not a choice of the individual: the emotion occurs in the psychic world of the person because of happening external of it, but also because of inner dynamics that are not easily recognizable: “The emotion should be considered a psychological construct in which different components are involved. A cognitive part aimed at the assessment of the situation-stimulus that causes the emotion; an element of physiological activation determined by the intervention of the autonomic nervous system; an expressive-motor part; a motivational part, linked to the intentions and to the tendency to act/react; a subjective part that is the feeling experienced by the individual. All these parts are interdependent and participate in determining the emotional experience” (Ricci-Bitti, 2008: p. 77).

This definition helps to understand that emotion is a very complex phenomenon which is woven throughout the life of every human being. There are no areas in which a human being feels no emotions: there can be situations in which emotions are hidden or showed; they can be in harmony with the actions that a man does, or they can be in opposition to these actions making them difficult or impossible. Sometimes the subject recognizes his emotions and is able to manage them profitably, sometimes, however, the subject is overwhelmed and the consequences are not always positive for his lives; finally, sometimes the subject censor his emotions, because he does not want or is not able to accept them. The complexity of this experience is enhanced by the fact that emotions are always inner activities in mutual exchange with the body: the emotion lives inside the body and influences it, but at the same time the body affects emotions.

These aspects (cognitive, physiological, expressive-motor, motivational and subjective) are interdependent and contribute to determine an emotional experience. Emotion—which is an “individual experience in a social dimension” (Camaioni & Di Blasio, 2007: p. 203)—is a complex and multidimensional experience, that can mediate the relationship with the environmental events and the behavioral responses of the individual.

The subject tries, time by time, to regulate his emotions by adopting strategies that can match the emotional experience and its external manifestation to socio-cultural situations and norms: “emotions are therefore a form of language, even if of a very particular type: at the beginning biologically and not culturally structured and self-semantic, that is, constructed of signals that are their own meaning or are part of their same meaning” (D’Urso & Trentin, 1990: pp. 93-94).

There is no other way to understand a certain emotion of living it and becoming aware of that state: “Emotions have a communicative function, both inside and outside” (D’Urso & Trentin, 1990: p. 125). This process is very important because consciousness is the root of our voluntary, intentional behavior (D’Urso & Trentin, 1990: p. 125). Emotions influence behavior. It is possible to think of carrying out a voluntary and intentional action only if one is aware of the emotions and its effects on the ego. This capacity for self-awareness is fundamental to respond to the winds that stimulate emotional modes and in general in the management of interpersonal relationships. The experience of feeling emotions is not a choice of a person: the emotion happens in the psychic world of the person on the solicitation of a fact external to it, but also for internal dynamics that are not easily recognizable: “Art, in all its forms, is part of this complex thesis, becoming an important mean for the recognition and management of emotions, becoming a privileged opportunity for the expression of one’s own human interiority. Education to Theatricality through the workshop of emotions, leads the individual to create a contact with his emotional world to describe it and communicate it with a language understandable to others (Oliva, 2018: p. 106 ).

It is clear that education to emotions is necessary for the existence of the person. Knowing how to live, express and tell one’s emotions is a big advantage both for cognitive functions (emotional intelligence) and as a fundamental resource for building authentic and positive human relationships.

It is essential that “the language of the body participates decisively in the regulation of the intensity of the emotions, because the emotional response is primarily defined at the physiological level. Emotions are always accompanied by bodily sensations and expressive behaviors” (Oliva, 2018: p. 108).

It is urgent to educate people to recognize and manage emotions, even because in today’s world, the society and in particular the trade industry, are very interested in the emotions of the human being. It is important to help people to recognize emotions in their complexity, so they can develop a personal balance without forgetting values, or the real substance of their own lives and the strength of their choices.

Through a process that allows every person to work on the relationship with the Ego and the others, the theatre workshop allows to use resources in order to be able to perceive emotional knots, inner conflicts, communication blocks and to handle with them. The theatrical workshop in relation to another human being becomes an instrument to tolerate strong emotions, to project them outside, to control them, live them and share them at a distance, until it becomes possible to reintroduce them inside ourselves. We can not always avoid the frustrations but we can learn to tolerate them, and theatrical activity can offer available alternatives to learn to dominate negative moods. The theatrical activity helps the human being to become aware of body language and be aware of behaviour, emotions and thoughts. This is the first step to have a genuine dialogue with our Ego and succeed in reaching full growth, acceptance and self-awareness.

The workshop is the “place of the possible, without judgment” becomes a tool to learn how to manage emotions, to project them outside of yourself, to control them, to live them, to share them and learn how to manage them.

8. Creative Movement and Neurosciences: The Laboratory of Relationships

“When a subject observes a body that is moving, his mind activates a phylogenetic principle of recognition and solicitation through which he begins to imitate and recombine the information received thanks to mirror neurons” (Oliva, 2018: p. 108). Thought and action, therefore, are interconnected: “The movement, in fact, constitutes the tool that is much more close to a sixth sense. In fact, the ability to anticipate what is going to happen in the space around us is inside the brain. “... perception is not only an interpretation of sensory messages: it is conditioned by action, it is its internal simulation, it is judgment, it is an anticipation of the consequences of action”. Before moving and carrying out an action, the brain calculates the position of one’s body, becomes able to relate with the surrounding space and confronts with the circumstances, proving to be much more similar to a simulator than to a computer that uses the movements of a body in a space to elaborate a stable model of reality, in balance between the senses and the thoughts, that is, those software that we use to give an explanation to the sensations” (Paloma, 2009: p. 130).

The creative movement activates a plurality of physiological mechanisms that involve the whole organism starting from the mirror neurons, which are the cells of the brain that come into action when you see a subject performing an action and that allows you to understand what he is doing. In fact, in the brain of a person who is looking to another, a mirror system is activated and the areas related to the movements that are being observed are triggered. The body moves even before moving, that is, it prepares to perform the gestures as if the subject would be the actual performer of that gestures.

This mechanism always starts, even if we do not realize it; so perception, action and cognition, traditionally considered distinct, are actually strictly interrelated. “Although we can state that any motor act is, in reality, a mental act, so the motor system for neuroscience is not only a passive performer but predisposed to take action to understand the intention of those who act: thought, knowledge, memory, emotions are connected to motor behavior” sensations (Oliva, 2018: p. 109). In this regard, Vittorio Gallese states: “Mirror neurons exemplify a neuronal mechanism that relates the actions performed by others with the observer’s motor repertoire. The observation of an action induces the automatic simulation of that action in the observer. This mechanism allows to understand the actions of others. [...] Every time we observe the actions of others, our motor system “resonates” together with the one of the observed agent. [...] Research carried out in the last decade has also shown that the mirroring mechanism is not confined to the domination of actions, but also concerns the domain of emotions and sensations” (Gallese, 2010: pp. 247-248).

The mirror neuron system allows the subject, through movement and the body, in an immediate way, to understand the intentions of others, but also to read and get in touch—to feel—emotions and sentimental states. This is so important importance if we consider the fact that the mirror neuron system changes and grows by learning, and it demonstrates “the decisive role of motor knowledge for understanding the meaning of the actions of others” (Rizzolati & Sinigaglia, 2006: p. 133).

We can summarize that in the observer’s brain, when he sees an action, is activated an anticipatory and predictive modeling of action at the motor level, because each person owns within himself the act, which is a potential act. The motor system, through mirror neurons, is not only able to reproduce the movements but also can act empathically, that is, it has the capacity to perceive emotionally what that movement is causing to the subject that is producing it.

“The discovery of mirror neurons opens new perspectives of research about the motor system and the creative movement. In addition, neurosciences have provided theater studies with various tools for analyzing the performative event and the relationship between actor and spectator. The study of mirror neurons, therefore, offers a unitary theoretical and experimental framework for the construction of the action on the stage and its ability to establish human relationships.

Every physical action staged by the actor is an intentional and motivated motor action, directed to a specific purpose; this action is immediately read by the viewer and allows him to understand the sense of the performance. The performative act becomes a communicative act within the scenic space, it is charged with a meaning that has a universal value and that does not need any semiological elaboration. Theatrical experience, therefore, as a formative activity, stimulates the different forms of learning, directing the creative energies of the subject towards the conscious construction of knowledge” (Oliva, 2018: p. 111). This process is not limited to an individual work of a person, but also concerns the relational and social dimension.

9. The languages Body Workshop: Exercises

The workshop stimulates the person to live in a renewed way his own sociality so the human being creates a relationship through the body and the movement. So the expressive arts workshop, through the use of languages becomes a laboratory of relationships. Of continuation, there are some of the many explorations that can be put into play for the discovery of non-verbal language (Oliva, 1999: pp. 178-209). They develop the body language in its three fundamental components: the gestures, that is a specific action of a part of the body that presupposes an intention of the individual towards the achievement of a precise end; the movement, that is the displacement of the body or part of it, and the physical action, or a movement capable of producing a certain objective.

The purpose of the laboratory is not to learn a technique; in the laboratory, there is not a model to be reached, rather that of elaborating one’s own language to arrive at determining one’s own conscious way of using it to communicate and relate to others. The workshop takes place in a playful atmosphere, the work must be based on “non-judgment”; it is an individual work in a group work; it is a “space of the possible”; the work methodology is improvisation (Oliva, 2015b: pp. 285-304); each person has the task of searching (experimenting and developing his own creative response to stimuli); every exercise is a means, not an end of work.

9.1. Part I—Discovery of the Elements of Body Language

General objectives of the laboratory practices

The objectives of this work phase are:

- Development of a mental and bodily state of relaxation, concentration and attention.

- Development of awareness of the general elements of body language.

Note: The two elements of the work are: the development of the communicative intention and the development and use of language. First of all, it is important to get out of the logic of everyday life (rules, anxieties, preconceptions, habits); each person must try to discover potential, limits and develop his natural pre-expressiveness. In general, all the exercises can be adapted by the subject in action or by the conductor in relation to the physical condition of the participants.

Exercises

1) The neutral position

The neutral position is a psycho-physical condition, the search for a neutral state; it is the starting point from which to develop any expressive and communicative action.

Take a standing position.

Keep the legs closed (not too much, in line with the shoulders), the knees slightly bent (abandon the stiffness).

Try not to think, to eliminate all thoughts and to listen to your body and your feelings.

Eliminate stiffness in the neck and shoulders.

Looking ahead, standing in one direction (you can work even with your eyes closed).

Feel your natural breath.

Relax, concentrate, listen to yourself.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

The neutral position is a state in which we tend towards neutrality; it is not a point of arrival but a research process. The practice leads the student to hone his ability to relax, listen and listen and be present. The neutral position is therefore not a simple initial moment to “enter” the laboratory, but a real listening practice.

2) De-mechanization

Assume the neutral position.

Soften muscle tension and relax knees. Give up thoughts.

It is preferable to work with closed eyes.

From the neutral position one arm is brought forward (for example the right one).

Take a soft gesture without tension.

The whole body begins to be segmented and de-mechanized starting from that arm. It is necessary to focus attention on the individual parts of the body that are used, not on the movement that is produced. Concentrate on only one part of the body at a time: begin to de-mechanize the fingers of the hand, one at a time, slowly. Experiment with the de-mechanization of body parts and stop: perceive the sensation of the gesture that is produced.

Then from the fingers reach the hand following the joints one at a time: the movement starts from the hand, then comes to the hand, then to the wrist, then to the forearm and elbow, then to the arm and shoulder, then to the neck and finally to the nape; then de-mechanization develops on the left side of the body: left shoulder, arm, elbow and forearm, wrist, hand and fingers.

Then de-mechanize the torso: torso (chest, abdomen), back, pelvis and hips.

Move to the lower limbs: thigh, knee, leg, ankle, foot and toes.

Every time a “piece” is de-mechanized it continues in the action without turning neutral again. The work develops by de-mechanizing and mechanizing the different parts of the body. It is not a question of producing a continuous movement but a de-mechanization that leads to the development of a form (increasingly complex as the different parts of the body are de-mechanized) which stops, is perceived and then starts again in its development.

At the foot, you can bring de-mechanization/mechanization even in space.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

Each articulation is an expressive possibility. We tend to use the limbs in their entirety, but there are endless possibilities of movement given by the different parts of the body. Becoming aware of it and learning to act with intention goes to enrich the vocabulary of non-verbal language. For this reason, it is better to avoid gross and fine movements in oneself, but focus on careful and meticulous research.

3) Shape

- First phase:

Take an abstract form with the body and describe yourself.

- Second phase:

Assume sequences of abstract shapes trying to use different body parts to create different and unusual shapes.

- Third phase:

From the neutral position, think about a shape and then realize the shape. Build a sequence of actions: “I think of a form and I realize a form. I come back neutral. I think of a form and I realize a form”.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

To give form means to say something precise, even if abstract. It is already an expressive and communicative action; it means maintaining an attitude. Becoming aware of one’s own forms becomes the first step to fill them with intentionality.

The practice of this exercise frees the possibilities of the body; it makes us look at the forms with which we constantly live reality with different eyes. At any time we are representative of our condition. Using all parts of the body and taking new forms also means engaging new ways of thinking and relating.

4) The gesture

Assume the neutral position. Enter a state of concentration, attention, relaxation and body control.

Make a gesture when you are focused. Keep the gesture. Feeling the gesture from within, must be an “important” gesture, must have a precise meaning. After making the gesture return to the neutral position and reconstruct it by moving the body suffering on the motivation from which the action starts. Build the gesture, with extreme calm, segment by segment (not a body shape but just a simple gesture). Hold the gesture, listen to the gesture, listen inside and then start again. You walk and create another gesture.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

Gesture work is a more detailed use of the form. It is about knowing how to break down physicality in all its articulations. It is not only a question of intention but also of rhythm and sensation.

Moreover, the gesture is psychology; it is not just a matter of controlling and moving a part of the body but of entering into a relationship with the world to say or get something: reflecting on the daily gestures made or suffered puts people in relation to their existence.

5) The walks

Walking in the empty space.

- First phase:

Walking in space. Walk as usual, with your own pace, your own pace, your natural gait, paying attention not to clash with others.

- Second phase:

Pay more attention to your walk. Now, start from the neutral position and walk. Control the speed, perceive the body better. Feel how your feet rest on the ground, how your knees bend, perceive the undulating movement of your hips and pelvis. Stop, return to the neutral position and start again.

- Third phase:

Walk starting from the neutral position. Pay attention to your feet and knees. Relax the knees by bending them slightly and walking. Free your ankles from weight, look for lightness. Experience the possibilities of movement of the feet by walking in different ways, let yourself be guided by the feet themselves. Experiment with different supports (point, heel, whole plant) and cross the steps. Check that there is no excessive basin ripple. Stop, start again and repeat several times.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

Walking and moving is an action that implies the development of autonomy and self-determination. In the stages of human growth, in addition to the conquest of basic trust and physical and muscular development, there is the conquest of the spirit of initiative: In the exercise of walking, the choice and personal reflection on one’s own movement is called into play : “Where to go? Why? How?”

For people who have difficulty walking, work can concentrate on this aspect by bringing it to elements of the body that can be used (arms, legs, head, etc.).

9.2. Part II—The Creative Movement

General objectives of the laboratory practices

The objectives of this work phase are:

- Development of rhythm perception.

- Definition of the use of non-verbal language in relation to rhythm.

- Exploration of the relationship between rhythm, sensation and non-verbal language.

Exercises

1) Warming-up exercises

Rhythmically walking while the arms and hands rotate.

Running on tiptoe. The body must feel a sensation of fluidity, flight, weightlessness.

The impulse for the run comes from the shoulders.

Walk with knees bent, hands on hips.

Walk with knees bent, gripping the ankles.

Walk with the knees slightly bent, the hands touching the out-side edges of the feet.

Walk with the knees slightly bent, holding the toes with one’s fingers.

Walk with the legs stretched and rigid as though they were being pulled by imaginary strings held by the hands (the arms stretched out in front).

Starting in a curled up position, take short jumps forward, always landing in the original curled up position, with the hands besides the feet.

Note. Every exercise on body language can be accompanied by work with music. From a methodological point of view, it is preferable to first develop a work on “silence” in which the different elements of body language (work on awareness) are explored and then associate these with sound.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

Even if the proposed activities are very simple, approaching the movement means putting one’s body under stress; it is, therefore, very important to propose some warming practices for muscles and tendons in order to prevent trauma.

2) Breathing

Inizio modulo.

To the ground. Take a lying position.

Place your hands at your sides, palms facing each other. To relax.

Feel the weight of the body that is crushed to the ground.

Start focusing on your breathing: feel the air entering your nose, fill your lungs and then exit. Do not speed up your breathing, try to enter a state of relaxation and calm. Put yourself in a state of listening to the air. Do not contract the abdomen, close the eyes, the facial muscles must be relaxed, the mouth slightly opened (to open the epiglottis the position is that of the yawn).

Listen to the sound of air entering and leaving naturally.

Inhale from the nose, exhale from the mouth.

Breathing swell alternately only the abdomen or just the chest.

Explore complete breathing: inhale and fill the abdomen and then the chest. Express by first emptying the chest and then the abdomen. To relate to one’s breath and the rhythm of the breath.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

Breath is a fundamental function for survival; every single respiratory cycle is composed of an inspiration phase (incoming air, a little shorter) and an expiratory phase (outgoing). The breathing process is automatic, that is, it takes place without our intervention thanks to the nerve centers, but we can also control the process; in everyday life it is rare to use full breathing; getting back in touch with the natural possibilities of the body means knowing how to use its possibilities in case of need.

The psychophysical situation of the whole body is determined by breathing. The management of rhythm and time rhythm of actions concern respimo, but also the emotional state.

Inizio modulo.

Acting on it the person has the opportunity to intervene on his emotional state in any situation, place and time; particularly in situations of agitation and emotional stress, entering a slow and deep breathing allows you to find a state of tranquility.

3) The rhythm of the gesture

Assume the neutral position. De-mechanize the body in relation to the rhythm of the music building sequences of gestures and forms.

Alternate moments with music and moments without music in the same work session.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

After having worked on the de-mechanization of the parts of the body (discovery of all its elements), we now work on the relationship between gesture and internal rhythm (combined gestures and forms in relation to breathing), internal), and external (in relation to music).

In this sense, therefore, it becomes important to finalize the perception of one’s own movement by channeling it into rhythm, thus giving physicality and concreteness to perception.

The exercise, therefore, works on a level of perception: starting from practical work—perceiving external sensations and translating them into a movement that “is inside” that feeling—a very interesting self-educational operation of listening, control and self-regulation of one’s actions in response to environmental stimuli.

4) The rhythm of the pelvis and the feet

Walking in space in relation to the rhythm of the music building sequences of steps (using the exploration of the previously developed walks: use of the feet and use of the basin).

Alternate moments with music and moments without music in the same work session.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

The perceptions and the translation of them into body movements extends beyond the peripheries. After having worked on the gestures, we now move in a more specific way to bring the trunk and the pelvis into play, very often they are “zones” of the body little explored but a place of great vitality. Actions and impulses to actions always pass from the center; it is, therefore, important to discover its potential.

After working on the walk and on the elements that make it up (feet and steps) a relationship now develops between displacements in space and rhythm.

5) I walk and dance rhythms and sensations

Use a musical dramaturgy containing a sequence of music of different musical genres (classical, blues, jazz, rock, folk, pop, etc.), but above all of different rhythmic-melodic-harmonic quality.

The dynamic consists of starting with a normal walk and transforming it into creative movement (using movements, gestures, shapes and steps) in relation to the rhythms of music. At the end of the music, the movement is brought back to the walk which is re-transformed again in relation to the subsequent music.

Dynamics: Simple walk → perception of the sensation and rhythm of music and transformation of the walk into a creative movement → transformation of creative movement into simple walking → perception of the sensation and rhythm of music and transformation of the walk into a creative movement → etc.).

Notes on the effect of the practice.

The objective of the activity is not to learn to dance a type of dance, but to have each to build a capacity for fluid creative movement and an adaptability to different situations and sensations beyond personal style preferences.

The expressive elements available are the walk (and its development), the gesture (and its expansions), the form (the movement to enter and exit the form).

The free composition of a sequence of exercises experimented with one’s own body, proposed in the first person and made to live through rhythm and melody is a work of great freedom for people.

With a simple exercise of composition, therefore, the process that the person operates is to connect the proposed movements, give them an order on a rhythm and on a sensation, continuing to transform, in the present, his creation.

9.3. Part III—Communicate Creatively with the Body

General objectives of the laboratory practices

The objectives of this work phase are:

- Recognize and express emotions through narrative body language.

- Tell ideas, thoughts, problems and stories through body language.

Exercises

1) Telling the emotions with the body: Sculpting the forms-emotions

I work in pairs in a group work. Initial position: in pairs in random order in space.

As a pair. “Sculptor and clay”: sculpting emotions and emotional states.

Define a series of emotions: anger, sweetness, fear, joy, sadness, joy, surprise, contempt, disgust, envy, shame, anxiety, resignation, happiness, jealousy, hope, forgiveness, offense, nostalgia, remorse, disappointment. In pairs each model, the other in an Image-Emotion.

Once the image is finished, the sculptor leaves the statue in the form for a few seconds, then the statue sends back to his sculptor what he felt (the sensation of the image, being manipulated, what eventual appeal was born in his work, what he felt, etc.). It is not a matter of “guessing” the sculpted emotion, but of postponing one’s own experience that does not necessarily coincide with that of the sculptor.

Note: The “sculptor” must visualize his image-emotion and then sculpt his companion like a statue: moving his arms, head, torso, legs, he can bend his knees and make his workmate lie down on the ground, or, on the contrary, raise it on tiptoe; you can define facial expressions by manipulating the face, representing the image to the mirror that will mirror it; the direction of the gaze can be defined by placing two fingers in front of the eyes and pulling an imaginary line towards the point where you want to direct the view.

The only constraints are those imposed by the body flexibility of the human statue. The “statue” must be malleable as clay, not as a rubbery and elastic material which, even after receiving a shape, returns to its original place. It is a matter of allowing oneself to be modeled without resisting, following the movements of the sculptor and remaining in the forms that are gradually sculpted. The “sculptor” can also give “consistency” to different plastic energies—that is, it can define different bodily tensions in relation to the force that it imparts in the manipulation.

This work is very delicate; touching the other is, in fact, an invasive action. It is necessary that the group climate has reached a good level of harmony and that the individuals have developed a good awareness of one’s body perception.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

Before sculpting the partner, each sculptor must concentrate both on the imagery of the form and on the feeling of emotion.

In sculpting the companion it is a matter of creating a non-verbal communication that does not only close itself in the final product—the image—but which is also attentive to the process.

These dynamics that do not—necessarily—involve immersion in a memory or a work of recovery of emotional memory are possible exercises for the age groups of children and young people. For children, the activity can only be set on a narrative level: you can “play” at first when giving yourself the forms of an emotion and then later on to sculpt the emotion in the body of the other.

Sculpting emotions, but also ideas (see the next exercise), is a precious work also in empathic and relational terms. The dynamics lead first to the development of a self-awareness of one’s emotions and then, through imaginative sculptures, to come to understand the emotions of the other. Manipulation leads to “transferring one’s own emotion into the other”; this implies that the “clay” experiences the emotion of the other on itself, learns to recognize it and to give it a name in relation to its own experience. This situation can have a significant impact in terms of affective education.

The body becomes central in this type of activity also in function of new research, empathy, in fact, is a cognitive process that originates from the ability to understand that others can experience emotions and desires and that they can do it in a similar or different way and that, as the latest neuroscientific research has shown, is also linked to mirror neurons.

2) Telling ideas with the body: Sculpting the ideas-forms

I work in pairs in a group work. Initial position: in pairs in random order in space.

In pairs. “Sculptor and clay”: sculpting ideas and problems.

Representing a series of ideas and problems linked to the group’s experience (work and unemployment, violence against women, discrimination; freedom, social relations, war, inter-generational confrontation, illness, care of the elderly, bullying, ecology, immigration and integration, difference of religion, school and education, etc.). In pairs each model, the other in an Image-Idea/Problem.

Once the image is finished, the sculptor leaves the statue in the form of a few seconds, then the statue sends back to his sculptor what he felt.

Variation: once the sculpture is finished the sculptor also joins with his own body to the image created (the sculpture becomes two people). Then the creation is discussed.

Teamwork. The images made by the couples can also be preset in groups and discussed.

Notes on the effect of the practice.

With the “sculpture of ideas” a new narrative plan is introduced: the story of one’s own ideas. The laboratory becomes a space for reflection where one can discuss issues related to life and society and where everyone is free to present their point of view.

Obviously, the themes introduced vary from group to group and from age to age group. By sculpting ideas, situations, conflicts the emotional sphere is obviously also involved. It is interesting to integrate this “more social” space of work with the affective aspects experienced previously.

10. Conclusion

Education to Theatricality revisits the history of theatrical pedagogy and performative practices and contextualizes them in the light of new pedagogical and scientific knowledge and it studies human beings and their capacity for expression.

At the center of his practice, there are languages and in particular the body.

Just because the person is the person at the center of the training process, the theater workshop promotes communication and develops creativity. At the same time, the renewed expressive capacity is a tool that can be applied to everyday life and in all contexts.

This process is based on several elements. First of all, the starting point of the workshop is not talent, nor technique but the naturalness of each person (the natural pre-expressiveness). Each person is endowed with his own diversity, uniqueness and inimitability: a body, a voice, an emotional intelligence, an ideational and reasoning capacity. On this basis, creativity is developed: in the laboratory, each person then creates his own artistic model that is not comparable to anyone else. Laboratory practice, therefore, does not work on fiction but on the truths of the person. The new models of communication, of attitude, are therefore not only used in situations of representation but become knowledge and skills that are always applicable. Concretely, this process is divided into two parallel paths: one focusing on the discovery of Ego, discovering personal skills trough a physical and emotional work. This path aims at self-awareness; to achieve this purpose it is important that the practice is continuously accompanied by self-analysis and reflection on what has been discovered. In fact the person will experience limits and potentialities of themselves. The theater workshop as a process of attribution of meanings can connect the action with thought and vice versa. For this reason, while giving ample space on the physicality and action, it does not neglect the essential moment of reflection; this allows to acquire a greater awareness of what has been accomplished. The reflection, such as promotion of the comparison, is designed as a central element because it allows to revise the process through the sharing of commonalities and differences of the experience. The aim of the conceptualization of the experience is to allow a greater understanding and help people to seek shared meanings” (Oliva, 2015e: p. 8). This is the idea of training in Education to Theatricality.

A second that foresees the use of what was learned in the communication relationship: The communication that foresees the presence in the “here and now” of bodies.

The contents of the laboratory are the languages, all experience starts and develops corporeality. The body, in fact, besides being the form with which we are in the world and we know it, is the instrument with which we relate to others. The pre-expressiveness that takes shape in the laboratory through the development of the creativity of body languages gives life to the Creative Movement.

The Creative Movement can then be defined as the succession in time and space of numerous creative acts; the creative act is an act in which the person consciously organizes to communicate action, emotion, and thought. Body work, emotions and communication have another effect: the person discovers new strategies and abilities to relate to others. The laboratory not only promotes self-esteem, self-efficacy, the production of ideas and problem solving but it offers a new interpretation to read and produce behaviors and attitudes. The studies and knowledge that the neurosciences are producing are very useful for this purpose, precisely because they are focused, in particular with mirror neurons, on the empathic question. This question is not detected as cultural or psychological element but on the physical data. A body that moves (actor) and performs an action generates in the viewer (spectator) a similar action of mirroring at the neuronal level. From pure action, we are also moving to the study of sensations. This means that the more the actor masters his own action (physical, emotional and sensory intention), the more the relationship with the spectator will be precise. On the other hand, when he will be a spectator, he will be able to read (or rather live) the communication of others.

In this context, the question of creativity is important in order not to reduce the communicative aspect to a mechanical, “mathematical” concept.

It is not a question of getting to codify every single aspect of the relationship, but of offering people a space where they can increase flexibility, the capacity for action-reaction, that of managing their own emotional state, the spirit of elaboration of ever new strategies and modalities to relate humanly (poetically) with others.

For these reasons, the expressive arts can be a great tool of involvement training; it can be an attractive vehicle for the transmission of knowledge and for the development of attitudes and skills. The experience of the laboratory involves the person in his own truth and humanity; the training process through art not only promotes creativity but also provides elements for reflection and develops practical skills for every day relationships and communication.