Fire Self-Extinguishing Cotton Fabric: Development of Piperazine Derivatives Containing Phosphorous-Sulfur-Nitrogen and Their Flame Retardant and Thermal Behaviors ()

1. Introduction

Utilization of cotton is encouraged in a variety of consumer markets because cotton is abundant, low cost, and is an adaptable starting material for new products development [1] . However, cotton is readily attacked by flame, microbes, and insects, requiring chemical modification for resiliency. In this paper, we will focus on making cotton twill fabrics resistant to attack by flame.

In order to meet fire safety regulations and expand the use of cotton in textile applications that require flame resistance, a significant number of flame retardant treatments for textiles were developed in the last century. The majority of these flame retardant treatments can be classified into four distinct groups: inorganic, halogenated organic, organophosphorus, and nitrogen based [2] [3] . Numerous studies have shown that the actions of phosphorus flame retardants are enhanced by the presence of nitrogen. Earlier works on phosphorus-nitrogen systems showed that such combinations produced greater flame resistance in cotton textiles at a lower level of phosphorus than phosphorus when used alone [4] -[6] . Unlike the halogen-containing compounds, which generate toxicity or may produce toxic gases, corrosive smoke, or harmful substances [7] , the phosphorous-containing flame retardants are known to transform into phosphoric acid during combustion or thermal degradation. This further causes the formation of non-volatile polyphosphoric acid that can react with the decomposing polymer by esterification and dehydration to promote the formation of char residue [8] [9] . The char residue can act as a barrier to protect the underlying polymer from attack by oxygen and radiant heat, achieving the purpose of extinguishing of fire.

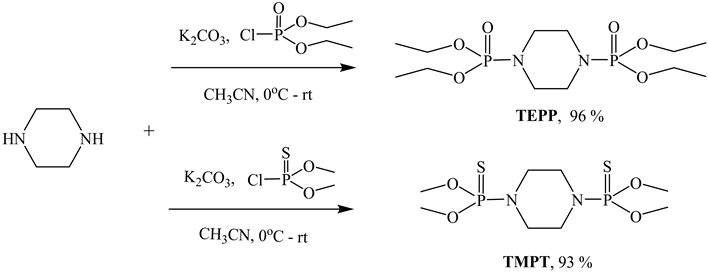

This research is focused on investigating the flame retardancy of Piperazine derivatives containing phosphorus-nitrogen-sulfur. Emphasis was placed on the synthesis and characterization of the phosphorus-nitrogen base tetraethyl piperazine-1,4-diyldiphosphonate (TEPP) and phosphorus-nitrogen sulfur base O,O,O’,O’-tetramethyl piperazine-1,4-diyldiphosphonothioate (TMPT) piperazine derivatives. Both flame retardant small molecules can be prepared from low cost materials and are the products of a coupling reaction between piperazine and phosphate or phosphonothioate derivative (Scheme 1). TEPP and TMPT were characterized by 1H, 13C, and 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The structure characterization and flammability of treated fabrics at different add-on levels were studied by the following methods: attenuated total reflection-Infrared (ATR-IR), vertical and 45˚ flammability (ASTM D-6413-11 and D-1230-01) [10] [11] , Limiting oxygen index (LOI) (ASTM D-2863-09) [12] , Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and Microscale combustion calorimeter (MCC). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was applied to examine the surface morphology of the unburned and burned areas of the control and highest add-on treated fabrics. Fabric treated with TEPP and TMPT

Scheme 1. Synthesis of TEPP and TMPT.

showed good flame resistance at low add-on levels due to the generation of high char content upon thermal decomposition and pyrolysis.

2. Experimental

2.1. Material

All reagents and solvent were purchased from Aldrich. The reagents were used without further drying or purifying; however, acetonitrile (CH3CN) solvent was dried before use by a Solvent Purification System (from Innovative Technology). In the synthesis, the reaction was conducted under nitrogen atmospheric conditions and the reaction progress was monitored using silica gel 60 F254 thin layer chromatography (TLC) (from EMD). In the testing experiments, the cotton cellulose which is 100% cotton fiber was obtained as twill fabric with the weight of 258 g/m2 (Testfabrics, Inc., Style 423). This fabric was desized (starches removed) and bleached and was free of all resins and finishes.

2.2. Synthesis of TEPP and TMPT

TEPP was prepared previously by a coupling reaction between one equivalent of piperazine and two equivalents of diethyl chlorophosphate in the presence of two equivalents of a base, anhydrous potassium carbonate (K2CO3) [13] . When the reaction was over, a white solid was filtered off and the filtered solution was evaporated to give an off-white solid as product in 96% yield with no further purification needed. In the same way the preparation of TMPT was carried out using dimethyl chlorothiophosphate instead of diethyl chlorophosphate. After evaporating the solvent, a white solid was obtained in 93% yield and no further purification was required.

Synthesis and Characterization of Tetraethyl Piperazine-1,4-Diyldiphosphonate (TEPP): To a solution of Piperazine (5.0 gm, 58 mmol) in dry CH3CN, Potassium carbonate (16.0 gm, 116 mmol) was added and the mixture was cooled to 0˚C. A solution of Diethyl chlorophosphate (16.7 mL, 116 mmol) in dry CH3CN was slowly added by addition funnel to the above mixture while stirring under nitrogen. After the addition, the reaction was allowed to warm up to room temperature and was monitored by TLC using 10% MeOH/EtOAC as an eluent and iodine as a staining reagent. When the reaction was over, a white solid was filtered off. The removal of the solvent gave a clear oil as product in 96% yield with no purification needed. 1H-NMR (400-MHz, CDCl3) δ-ppm: 1.25 (t, 12H, -CH3), 3.38 (s, 8H, -CH2-N), 3.88 (m, 8H, -CH2-O-). 13C-NMR (400-MHz, CDCl3) δ-ppm: 16.4 (d, JC-P = 28 Hz), 40.2 (s), 61.5 (d, JC-P = 20 Hz). 31P-NMR (400-MHz, CDCl3) δ-ppm: −0.4 (s).

Synthesis and Characterization of O,O,O',O'-Tetramethyl Piperazine-1,4-Diyldiphosphonothioate (TMPT): TMPT was synthesized in the same way by using Dimethyl Chlorothiophosphate in the place of diethyl chlorophosphate. The removal of the solvent gave a white solid in 93% yield and no further purification was required. 1H-NMR (400-MHz, CDCl3) δ-ppm: 3.23 (t, 8H, -CH2-N-), 3.64 (d, 12H, -CH3). 13C-NMR (400-MHz, CDCl3) δ-ppm: 45.5 (t), 53.5 (d, JC-P = 20 Hz). 31P-NMR (400-MHz, CDCl3) δ-ppm: 78.1 (s).

2.3. Characterizations

All characterizations on TEPP were done previously [13] .

2.3.1. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

1H, 13C and 31P experiments for TMPT were performed on a Varian 400 MHz instrument using deuterated chlo- roform (CDCl3) as a solvent. In phosphorus experiments, 31P was given in δ relative to external 85% aqueous Phosphoric acid (H3PO4).

2.3.2. Fabric Treatment

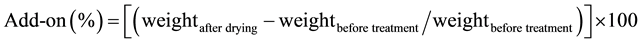

The required quantity of each chemical was first dissolved in a minimum quantity of water (for TEPP) or CH3CN (for TMPT) then the solution was poured into a shallow container that had the twill fabric sample laying flat. The fabric was then soaked in this solution for one hour. After that, the fabric was subjected to a padder (Birch Bros. Southern, Inc.) at 10 psi, then a drying oven (model LTF 146491, Mathis USA, Inc) at 100˚C for 5 min and finally a curing oven (model LTE 18795, Mathis USA, Inc.) at 165˚C for 5 min. Once taken out of the curing oven, the fabric was immediately placed in a desiccator to cool to room temperature and its weight was obtained after cooling. All samples were weighed before and after the treatment and the values were fitted to the Equation (1) to obtain add-on percents (or add-on levels):

(1)

(1)

2.3.3. Attenuated Total Reflection-Infrared (ATR-IR), and Thermogravimetric Analysis-Fourier Transform Infrared (TGA-FTIR) Spectroscopy

These experiments were carried out as described in literature [14] . For ATR-IR (Bruker Inc.) experiment, a total of 64 scans of the analyzed spectra region 4000 - 600 cm−1 were recorded for each sample with a resolution of 4 cm−1. In TGA-FTIR experiments, the FTIR spectra (Bruker Inc.) were obtained between 100˚C - 550˚C in the 4000 - 600 cm−1 region. At the end of these experiments, all spectra were reconstructed using OriginPro 9.0 software. This software helps support 3-D spectra showing the evolution of gas products in the course of thermal decomposition of treated fabrics as a function of both wave number and temperature. In ATR-IR and TGA-FTIR experiments, the spectra were obtained only on control and highest add-on treated fabrics. For TGA (TA Instruments), the measurements were carried out in a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.3.4. Vertical, 45 Degree Angle Flammability and Limiting Oxygen Index (LOI)

Control twill and all treated fabrics were subjected to the vertical flammability (The Govmark Organization, Inc.), 45˚ angle flammability (The Govmark Organization, Inc.) and LOI (Bynisco Polymer test) tests. In these tests, the specimen sizes were 30 × 9, 15 × 6 and 13 × 6 cm for vertical and 45˚ angle flammability and LOI, respectively. 45˚ angle and vertical flammability, as well as, LOI experiments were carried out for all of these samples. In the 45˚ angle flame test, a strip of fabric was inserted in a frame and held in a special apparatus at an angle of 45˚. A standardized flame was applied to the surface near the lower end for 10 seconds. The time required for the flame to travel the length of the fabric and break the trigger string was recorded, as well as the fabric’s physical reaction at the ignition point. In vertical flame test, a specimen was positioned vertically above a controlled flame and exposed for a specified time, and an afterglow time was measured. Char length was measured under a specified force and any evidence of melting or dripping was noted. In the LOI test, a small sample of fabric was supported vertically in a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen flowing upwards through a transparent chimney. When the upper end of the sample was ignited, the subsequent burning behavior of the sample was observed to compare the period for which burning continued or the length of sample burned. Minimum concentration of oxygen was determined by testing a series of samples in different oxygen concentrations.

2.3.5. Microscale Combustion Calorimeter (MCC)

In this test, the sample was placed in a sample holder (cup) located at the top of the sample mounting post. A thermocouple passed through the center of this post with its tip at the platform on the top to measure the temperature of the sample cup. The assembly was inserted into a furnace so that the sample, cup, and post were inside the furnace. In this experiment, the heat release combustion was determined based on the oxygen depletion, which relates directly to oxygen concentrations and flow rates of the combustion gases involved in the combustion process. At the end, an average value of three repetitive measurements is reported.

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Unburned samples and samples from burned areas of the control, 7-TEPP and 3-TMPT fabrics before and after vertical flammability test were examined using the Philips XL 30 ESEM with the magnifications of 1500× and a setting of 12 kV. For analysis purpose, all samples were coated with gold.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of TEPP and TMPT

TEPP and TMPT were prepared in excellent yields of 93% and 96%, respectively (Scheme 1), and all starting materials were available at low cost. No purification was required at the end of the reaction and therefore made the synthesis very accessible. TEPP dissolved readily in water but TMPT failed to dissolve. Moreover, TMPT isn’t soluble in many organic solvents such as methanol (MeOH), ethanol (EtOH), isopropanol (i-PrOH), hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). TMPT is partially soluble in acetone, ethyl ether, tetrahydrofuran (THF) and CH3CN, and it is completely soluble in chloroform (CHCl3) and dichloromethane (CH2Cl2). Like TEPP, TMPT is very stable at room temperature over a long period of time (more than two years for TMPT and one and half year for TEPP).

The chemical structure of TMPT was studied by NMR, and its data were listed in Table 1 together with TEPP data for comparison. From Table 1, it is clear that sulfur influences the chemical shift and splitting pattern of proton, carbon, and phosphorus peaks. While the signal for piperazine protons is triplet for TMPT, it is singlet for TEPP. Although in both cases the protons appear at >3 ppm, it slightly shifts upfield for TMPT due to less electronegativity in sulfur. In 13C NMR, a triplet and a doublet are observed for two carbons of TMPT while three doublets are seen for all three carbons of TEPP. Furthermore, phosphorous in TMPT resonates at 78.1 ppm, but phosphorous in TEPP appears at −0.4 ppm which is within the normal range of the chemical shift for acyclic phosphoric acid amides −16 to + 40 ppm [15] . When replacing sulfur by oxygen, regardless of the phosphorous functional grouping, a large upfield shift occurs [15] . This change could be explained by the total paramagnetic tensor and the variation of d orbital population on the P atom by dπ - pπ bond back-donation [16] . d orbital density (population) of 31P is larger in P=O than P=S, and the increasing in d orbital density results in an increase in paramagnetic property, like the anisotropic induced magnetic field effect. As the paramagnetic property increases, an upfield chemical shift (δ) for P is observed for P=O relative to P=S. This upfield shift also happens when decreasing atomic size results in a weakening in the back-bonding [16] .

3.2. Fabric Treatment

The add-on values obtained for both types of fabric after treatment are summarized in Table 2. For TMPT, the choice of solvent is critical to the dissolvability of the compound, but there is no best candidate among the solvents mentioned in sec 3.1 for treatment process. However, CH3CN was selected as a solvent due to its solubility and slower evaporation rate at room temperature. The loading levels used in this process are similar to those used in the studies of the effectiveness of organophosphorus FRs for cotton textiles [17] [18] . Furthermore, they are also recommended by industry for goods treated with similarly structured compounds to pass flammability testing [19] .

![]()

Table 1. NMR data of TEPP and TMPT (400 MHz, CDCl3): Chemical shift δ (in ppm) and coupling constant J (in Hz).

![]()

Table 2. Add-on (wt%) obtained for twill fabrics treated with TEPP and TMPT.

In general, the treatment does not impart stiffness or discoloration on the fabric samples.

3.3. ATR-IR, TGA and TGA/FTIR

3.3.1. Attenuated Total Reflection-Infrared (ATR-IR) Spectrometer

It is widely known that flame retardants influence the burning behavior of fabrics. To understand their effects, it is important to gain knowledge of the chemical components on the treated fabrics before the burning. In this experiment, the IR using ATR was employed to examine the functional groups on the surface of the control, as well as, the highest add-on treated fabrics, and the results are shown in Figure 1. Although the data were collected in a wide range, much of the differences can be observed between 1000 and 650 cm−1.

As seen in Figure 1, 7-TEPP and 3-TMPT do share two common figures: the peak characteristics of P-N(C)-C- and P-OC at around 814 - 796 cm−1 [20] . When thoroughly examined, the two spectra reveal their differences by their signature peaks. The spectroscopic feature at 722 cm−1 is found for 3-TMPT, which corresponds to the stretching band of P=S [20] [21] . At 2980 cm−1, CH stretch in aliphatic chain of O-C-C group of 7-TEPP appears as a small sharp peak [20] . Based on these analyses, it is evident that both chemicals remain intact during the treatment process for the fabrics.

3.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Figure 2 compiles TGA curves from 30˚C - 600˚C of the control and treated fabrics, as well as, the two flame retardants. Data for onset of degradation and residual weight at 600˚C (in percentage relative to the weight at 100˚C) are included in the figure. In a nitrogen atmosphere, all the treated fabrics, TEPP, and TMPT exhibit mono-, bi- and trimodal mass-loss curves, respectively.

With regard to the control, the TGA curve shows the losing mass starting at 300˚C, then displaying a turning point at 320˚C that is where the rate of its mass loss reaches its maximum. It then continues losing more weight until it reaches 85% weigh loss close to 600˚C. During this process, cotton produces volatiles including combustible and non-combustible species at around 350˚C. At a higher temperature, the degradation generates a smouldering phenomenon, leading to a slower mass loss [22] .

The onset of degradation of the two chemicals takes place at 173˚C and 186˚C, and that of the treated fabrics initiates roughly at 250˚C and 300˚C. Evidently, the flame retardants lower the heat resistance of the bulk material as compared to the control. Thermal degradation curves of treated fabrics normally comprise of at least two stages: the first is the degradation of the flame retardants, the chemicals, and the second is the degradation of main materials, the fabrics. Depending on concentration of the flame retardants on the fabrics, the first stage may or may not be obvious. It is well known that phosphorus additives reduce the onset temperature for the 2nd stage of treated cellulose by 50˚C - 150˚C [14] [23] [24] . While the onset temperature for the second stage of all TEPP fabrics ranging from 240˚C - 257˚C follows the pattern, it occurs later from 290˚C - 300˚C for all TMPT

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 1. ATR-IR spectra of the control and treated fabrics before burning: full spectra (a) and expanded region (b).

![]()

Figure 2. Degradation thermograms of the control and treated fabrics and both compounds.

fabrics. Surprisingly, at 2 wt%, the onset temperature of TEPP fabric is 50˚C lower than that of TMPT fabric. Furthermore, TMPT fabrics have the second stage onset temperature very close to the onset temperature of the control.

Although both types of fabric achieve add-on values close to each other, their char residues are significantly different. As seen in Figure 2, the mass loss of all treated fabrics is much lower than that of the control. Again, phosphorus flame retardants obviously promote char generation, and therefore, flame resistance in the treated fabrics. While TEPP chemical provides much less char residue than TMPT chemical, its treated fabrics have much higher char yield when compared with TMPT fabrics; therefore, an explanation was sought for the fact that TEPP was better as a flame retardant than TMPT. In the molecular structure of TEPP and TMPT, two effective flame retardant elements P and N are present. However, these two structures differ from each other in two aspects: the number of carbons in phosphorus moiety and the atoms to which the phosphorus are being attached. Being one of the key elements for flame retardant property in polymeric systems [25] [26] , sulfur is supposed to enhance the flame retardancy in TMPT fabrics; as a result, TMPT fabrics are expected to yield higher char residue than the TEPP fabrics. The same dimethyl phosphonothiate, as in this study, does not always show its superiority as flame retardant over diethyl phosphonate when applied on cellulose [27] -[29] . In this case, depending on the bond between the phosphonothioate and/or phosphonate to cellulose, the phosphonothioate may or may not provide higher char yield at the end. While an extra carbon in phosphorus moiety in TMPT may not be the main contributor to the difference in the formation of the char as seen in other derivative [14] , it is likely that when applied onto cotton fabric the sulfur influence the thermal decomposition of TMPT which could reduce sulfur’s synergistic effectiveness in the process of forming char.

3.3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis-Fourier Transform Infrared (TGA-FTIR) Spectroscopy

By coupling TGA with FTIR, the real-time gaseous products are detected in the whole thermal degradation process. During the experiment, the FTIR data are plotted one after the other with a total of 90 scans to form a 3D spectrum of the functional groups of the evolved gases, which are shown as a function of both wavenumber and temperature. A comparative study of this process was performed for 7-TEPP and 3-TMPT and spectra output are shown in Figure 3.

As shown in Figure 3, it is obvious that the two evolution profiles share some similar features at around 250˚C (for TEPP) and 300˚C (for TMPT). Previously, it is reported that these features are the signals of functional groups coming from water vapor, hydrocarbon OH, CO2, CO, hydrocarbon C-H, C-C C=C gases of the main material and the flame retardants [14] [30] . Besides these common features, they reveal their differences in other signature peaks. While characteristic absorption peaks of EtOH in TEPP appear at around 1400 (CH3) [31] and 1299, 1045 and 900 cm−1 (C-O) [32] [33] , the characteristic absorption peaks of MeOH in TMPT show up at around 1094 and 1040 cm−1 (C-O) [30] [32] ; however, the absorption peak for CH3 and two absorption peaks

![]() (a)

(a)![]() (b)

(b)

Figure 3. Volaltiles released out during thermal degradation of 7-TEPP (a) and 3-TMPT (b).

for C-O at 1299 and 900 cm−1 in TEPP are feeble. It should be noted that for EtOH, such less sensitive C-O absorptions at these positions compared with a much more sensitive C-O absorption at 1045 cm−1 position has been observed before [14] [31] . In Figure 3, there appears two distinct stages for 3-TMPT, presumably the decomposition of flame retardant and the decomposition of treated fabric. Although, the same mechanism takes place in 7-TEPP, the former happens so close to the latter that the peaks’ absorption for the flame retardant is not so pronounced as in the case of 3-TMPT. Especially, at around 3000 - 2850 cm−1, the absorption peaks for CH2 and CH3 of the flame retardant in 7-TEPP are not observed while they can be seen easily in the other case [14] .

In addition to signature peaks of MeOH, 3-TMPT 3D spectrum exhibits three new types of peaks at 1263 and 1178 cm−1 (SO2) [34] [35] , 931 cm−1 (P-N) and 824 and 723 cm−1 (P=S) [20] [21] . Overall, the intensity of most peaks in 3-TMPT is superior to that of 7-TEPP peaks in contrast with the lower concentration of TMPT on the fabric. A matter of supreme significance is more peak signals appear in the 3D spectrum of 3-TMPT than in 7-TEPP. These differences imply that TGA data is supported by FTIR data that the more gas products are released from the thermal decomposition of 3-TMPT fabric, the less char is formed at the end.

3.4. Flame Retardant Performance

Vertical and 45˚ angle flammability and LOI are important in the evaluation of the flame retardant properties for treated fabrics. The details of all three tests have been described elsewhere [24] [36] . At the end of the vertical flammability test, the afterflame and afterglow time are recorded and the char length is measured. The ease of ignition may be defined as the facility with which a material can be ignited under given conditions of oxygen concentration. In this test, the LOI value is the minimum percent of oxygen (in an oxygen-nitrogen mixture) required to sustain the burning for 2 inches or 3 minutes, whichever comes first.

Figure 4 comprises the images taken after the flammability tests and Table 3 summarizes the test results for the control and all treated samples. During the vertical testing, there was no occurrence of afterglow burning upon the removal of the flame, as well as no melting or dripping during the burning of all TEPP and high add-on TMPT samples. However, both types of fabric did display afterflame burning at all add-on levels. From Table 3, it is obvious that all TEPP fabrics except 1.3 wt% have shorter char length and afterflame and afterglow time when compared with the control. Concerning the char length and afterglow time of TMPT fabrics, neither displays shorter distance than the control and only 0.8-TMPT shows a glowtime that is almost four times less than that of the control.

From Figure 4 and Table 3, 45˚ angle flammability test shows the effectiveness of TEPP and TMPT as flame retardants at high add-on levels and in all cases, treated fabrics are classified as class I textiles. All TEPP fabrics except 1.3-TEPP do not exhibit ignition after removing the flame. Although containing the same add-on level of 2 wt%, TEPP fabric does not have flame spread but TMPT fabric does display 52 seconds of burning.

The average LOI values during the LOI test for all samples are also included in Table 3. At similar add-on

![]()

Figure 4. Vertical (top) and 45˚ angle (bottom) flammability tests results of the control and treated fabrics.

![]()

Table 3. Vertical flammabiliy (ASTM D-6413-11), 45˚ angle flammability (ASTM D-1230-01) and LOI (ASTM D-2863- 09) of different add-ons (wt%) of treated fabrics. All values for vertical and 45˚ angle tests are averages from two observations on the same fabric type.

(a)Class 1: textiles are considered by the trade to be generally acceptable for apparel and are limited to the following:

(b)DNI: did not ignite. Average time in seconds of flame spread for specimens of fabric which ignite as received. If specimen does not ignite, DNI is reported for the sample.

・ Textiles for which no specimen ignites.

(b)DNI: did not ignite. Average time in seconds of flame spread for specimens of fabric which ignite as received. If specimen does not ignite, DNI is reported for the sample.

levels 0.8 wt%, 1.3 wt% and 2 wt%, there appears a significant difference in LOI between the two types of fabric: the flame retardant action of TEPP is superior to TMPT. When compared 1.3-TEPP with 3-TMPT, the former has a lower add-on level than the latter but it achieves a higher LOI value. In studying the ease of ignition, fabric samples are evaluated based on the minimum amount (in percent) of oxygen to sustain a flame when a sample is burned in a combination of nitrogen and oxygen [37] [38] . While 1.3- and 2-TEPP and 2- and 3-TMPT can be classified as slow burning, 5- and 7-TEPP are considered self-extinguishing. Among them, low add-on level 0.8-TMPT is categorized as flammable in air like the untreated fabric.

3.5. Microscale Combustion Calorimeter (MCC)

Figure 5 compiles the heat release curves of control and treated fabrics. The flammability parameters such as heat release combustion (HRC), total heat release (THR) and temperature of maximum of heat release combustion (Tmax) were determined and the results are reported in Table 4.

The thermal decomposition of the control starts at less than 300˚C. The decomposition, as indicated by rising HRC, intensifies as the temperature is increased. It then reaches a maximum point at around 367˚C and ends at around 425˚C with an estimated value of 8.5 kJ/g in THR. Significant reduction in THR, HRC and Tmax are noted when the cotton fabric is treated with the flame retardants. Also, a “shoulder” behavior starts appearing at lower temperature for high add-on levels of TEPP fabrics. Such dropping in MCC parameters accompanying the formation of an early peak, is well known empirically for cotton fabric treated with flame retardants [14] . As seen in Figure 5, Tmax is lower in all TEPP samples as compared with TMPT samples. Upon a closer look at 2 wt% MCC curves of both types of fabric, a lower Tmax value with a higher HRC values are found compared to the next lower add-on samples. As the concentration of TEPP and TMPT increase, the initial decomposition temperature, THR and HRC, continuously decrease. It is noted that all treated fabrics have lower THR, HRC and Tmax values compared with the control and at similar add-on levels, all values of TEPP samples are lower than those of TMPT samples. The “shoulder” between 240˚C - 260˚C is owing mainly to the process of dehydration and decomposition of FRs to form protective chars [13] [14] . The protective layer in turn prevents the underlying cotton from igniting and reduces the normal thermal degradation of cotton and structural disintegration of the char to release volatiles and gases. After the burning of the FRs, the main material starts to burn which gives rise to the second peaks at around 280˚C - 290˚C and 320˚C - 340˚C. The same as the shoulder, these peaks decrease with increasing add-on values.

![]()

Figure 5. The heat release combustion curve of the control and treated fabrics.

![]()

Table 4. Microscale combustion calorimetry data (reported value is the average from three observations on the same fabric sample).

(a)THR: total heat release; (b)HRC: heat release combustion; (c)Tmax: temperature of maximum heat release combustion.

Micrographs of unburned and burned control and 7-TEPP and 3-TEPP are displayed in Figure 6. The burned samples were collected from the area where the flame contacted directly with the fabrics, which turned the fabrics to char.

As seen in the unburned samples, the surface morphology of treated fabrics doesn’t look as smooth as the control; however, in all cases, all the fibers are still intact and they look like twisted ribbons or collapsed and twisted tubes. Under the influence of flame and heat, the shape and the appearance of the control fibers are completely destroyed. In contrast, the burned/treated fibers still hold up very well although there is a cut in a fiber of 3-TMPT fabric. Furthermore, formation of a shaggy (burned 7-TEPP) or blistery (burned 3-TMPT) coating wrapping around each fiber as a layer is obviously observed. The appearance of this layer may be explained as being primarily due to the formation of gases formed by a burning mechanism of the chemical components of flame retardants during the thermal decomposition. This result indicates that the structure of the chars on the surface of each fiber provides the resistance of heat transfer and retards the degradation of underlying materials effectively, therefore combustion could not be self-sustained.

4. Conclusion

A phosphorus-piperazine was modified into a derivative form (TMPT) with a different phosphoryl group; its

![]()

Figure 6. SEM microgarphs with a magnification of 1500× of the unburned (top) and burned (bottom) samples.

Figure 6. SEM microgarphs with a magnification of 1500× of the unburned (top) and burned (bottom) samples.

effectiveness as a flame retardant for cotton was compared to that of TEPP, another derivative. The main differences in the structure of TMPT were that sulfur replaced oxygen and one carbon was reduced in phosphorus moiety. TMPT was prepared in a simple and effective one-step reaction giving an excellent yield (93%) of product. Its structure was confirmed by NMR technique and compared to that of TEPP, a previously synthesized derivative. ATR-IR data revealed the presence of the main functional groups of both flame retardants indicating their stability during the treatment process. Tests performed on TGA showed that char yield for TEPP samples is higher than that of TMPT samples, and TEPP samples provided lower onset of degradation than TMPT ones. Furthermore, TGA-FTIR data showed more functional groups for gas products forming from the thermal decomposition of TMPT compared with TEPP. Fabrics treated with TEPP passed the vertical flammability test starting at the levels of 5 and 7 wt% add-ons and all treated fabrics are regarded as class I fabrics during 45˚ angle testing. TEPP samples had higher LOI values when compared with TMPT samples at similar add-on levels. In the MCC experiment, the smaller values obtained for THR, HRC and Tmax for all TEPP samples showed a better reduction in heat of combustion. For SEM study, both TEPP and TMPT formed a layer wrapping around the cotton fibers to protect them from being destroyed by heat and flame. The inferior action of TMPT could be attributed to the ability to degrade into more gas products arising from the sulfur atom attached to the phosphorus in phosphorus moiety. Further study on durability properties using Standard Laboratory Practice for Home Laundering will be carried out and data will be presented in future publication.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by the United States Department of Agriculture. We thank Dr. Krystal R. Fontenot for helping us with EndNote software.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.