Architecture 007: Operative Environments in the Pursuit of Strategic Advantage ()

1. Introduction

Christoph Lindner acknowledges in the reader The James Bond Phenomenon that “rethinking the Bond phenomenon has come to dominate Bond criticism in recent years” (Lindner, 2003: p. 6). After all,” he writes, “James bond is anything but a stable cultural signifier, and keeping tabs on this agent of cultural change requires both constant scrutiny and regular revision.” James Bond’s legendary status as womanizer draws attention to the film series’ representation of sexuality and the Cold War, as Cynthia Baron writes in the above mentioned reader, “thus disclosing a reworking of images of female sexuality in line with the requirements of a “liberated” male sexuality…” (Baron, 2003: p. 135). This image of sexuality is well summed by Tony Bennett and Janet Woolcott in their book Bond and Beyond: The Political Career of a Popular Hero: “although Bond’s success with women continues unabated, the sexual attractiveness of the Bond character is no longer played straight because Bond’s sexuality has become dependent on a fetish for machinery, cars, guns, motorcycles” (Bennett & Woollacott, 1987: p. 20). While the inevitable nature of Bond’s sexual relationships has not changed much, the emergence of the operative character of the Bond girl perhaps establishes a tendency, similar to an already established trait in Bond’s character, for her to opportunistically operate the physical surroundings in the pursuit of strategic advantage. Architecture, and its spatial tropes, lend a helping hand in the formulaic binary Bond vs. Bond girl. Perhaps that hand, this time, clearly prefers diamonds to guns.

Drawing on the cultural stereotype of a male point of view, the narrative formula of the famous Bond Girls is nothing short of unoriginal—physically beautiful. They possess an innate or acquired exotic skill, which places the girl in the shadow of an extravagant villain as a henchwoman or is, through a glamorous unfolding of the plot, being persecuted by that same villain.

As a part of the same narrative cannon, James Bond acquires control by sleeping with a beautiful woman, whether she is a secret agent, a professional, a villain, or just a damsel in distress. A selection of Bond films is used to illuminate how the architectural decor in various scenes of seduction allows the female protagonist to gain control over James Bond.

2. Dr. No (1962)

Sylvia Trench, being the first Bond girl to ever appear onscreen (in fact, audiences meet Sylvia before being introduced to James Bond), is a classic example of a Bond girl (Figure 1). As the girl who surprises Bond at his apartment by playing “sexy golf,” Dr. No (1962) introduces her as Bond is shown walking in on Sylvia, who is dressed only in a man’s long-sleeved shirt (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Sylvia Trench (Eunice Gayson) in Dr. No. Dir. Terence Young. Perf. Sean Connery, Ursula Andress, Bernard Lee. Eon Productions 1962. Film.

Figure 2. Sylvia Trench (Eunice Gayson) and James Bond (Sean Connery) in Dr. No. Dir. Terence Young. Perf. Sean Connery, Ursula Andress, Bernard Lee. Eon Productions 1962. Film.

Suspended in the uncertainty of the screen moment the audience might not take into consideration that Sylvia Trench has arranged this situation. She leaves the door unlocked, and she positions herself perfectly in line of sight so that she is the first object Bond sees upon entering. Golf balls are strewn about the floor as she is standing in the middle of it all, leaving Bond no other option but to walk into her arms. Bond’s hotel room appears as he left it, except now there is a half-naked woman in it. She takes a common image from Bond’s memory, his own room, and barely alters it.

In addition to what she does, what she doesn’t do further enhances her unconventional set-up of the space for seduction. Sylvia avoids lighting candles, dimming the lights, or arranging other attributes of the romantic cannon; she alone is the object that stands out in the room. Her confidence is communicated in her stance: although there are various options for seating and supporting herself, she does not lean against the wall or drape herself across a chair. She achieves her desired result when Bond agrees to stay longer than he intended after initially claiming that he must leave immediately (Sylvia Trench: “When did you say you had to leave?” James Bond: “Immediately...almost immediately.”). And as if to finalize her offer as a proposition that cannot be refused, she hands him the golf club, silently commanding him to hold it as she wraps her arms around his neck. This sequence of events supports the hypothesis that Sylvia Trench knows how to successfully exploit the spatial qualities of a bedroom as well as the objects in it, a skill that many Bond girls must have if they are to achieve control in seducing Bond.

3. You Only Live Twice (1967)

The Bonds series can be credited with establishing a novel convention: the architecture of the villain is stylistically distinct from the architecture of good and “noble” intent. However, it is difficult to make the call of villainous or noble intent with seduction scenes due to the misleading nature of seduction. What appears as a romantic storyline on the movie screen is most often a tainted relationship: a quest for information, a cover-up of identity, or a false night of comfort. The revealing of a seduction scene’s true motivation is almost as essential in the 007 formula as the seduction scene itself.

An excellent case of this reveal occurs in You Only Live Twice (1967), where Ling aids in the staging of Bond’s death. How did Bond allow this to happen? A probable answer is that Ling gave him no choice, similar to Sylvia Trench’s set-up. The pre-credit sequence shows Bond and Ling in bed together sharing an intimate moment. The audience does not know how they end up in this situation, but from Ling’s over-confidence (which is another developing trait for Bond girls in control) one can assume that she has had more than a minor part in initiating the seduction. While in mid-conversation with Bond, she casually gets up, steps down from the platform elevating the bed and strolls over to a partition wall (Figure 3). By pressing a button on the end of this wall, she flips the bed into an upright position with Bond still in it: this creates the perfect opportunity for gunmen to enter the scene and murder the British agent. Of course, the audience is not alarmed. They assume their hero will soon return, as his so-called death occurs not five minutes into the film. More importantly, what they now realize is that the seduction scene took place because of covert intent, and what remains is a crime scene. The emergence of henchmen reveals that this crime is the result of collaboration, and although she is not the one shooting the gun, Ling is presumably the key accomplice to this attempted murder. Pivotal is her success in executing the task of getting Bond into bed.

The bed is a common piece of furniture, but at the touch of a button this place intended for rest becomes a contraption for torture and almost immediate death. Clearly this bed has been tampered with; however, whether Ling is the one who does the mechanical tampering does not matter. She ultimately acquires control of this mechanism, which is significant because any one of those henchmen could have physically pressed that button. This moment of control is an accurate portrayal of feminine dominance in a bedroom setting: it is effortless; it reduces sexual attraction to an act. The amount of displacement that Bond experiences is enormous in comparison to the effortless, almost undetectable thrust that Ling’s smallest finger exerts on one button (Figure 4).

One may suspect a similar sequence of events because of her insincere tone and her lack of enthrallment with Bond’s pillow talk. The beauty of her ill-intentions becomes a visible work of art after the henchmen finish shooting: once lodged vertically in the wall, the outline of the bed creates a composition with a glowing pendant lamp on the left and wooden slats that form a backlit screen on the right. The camera shows this view straight on, somehow making the bullet holes in the wall emerge as artistic punctuation. It is Ling who paints this perfect murder scene. Ling carefully composes this seduction so as to set Bond up for death, and she has done it with

Figure 3. Ling (Tsai Chin) in You Only Live Twice. Dir. Lewis Gilbert. Perf Sean Connery, Akiko Wakabayashi, Mie Hama. Eon Production, 1976. Film.

Figure 4. Ling (Tsai Chin) in You Only Live Twice. Dir. Lewis Gilbert. Perf Sean Connery, Akiko Wakabayashi, Mie Hama. Eon Production, 1976. Film.

exceptional ease of architectural manipulation.

4. Die Another Day (2002)

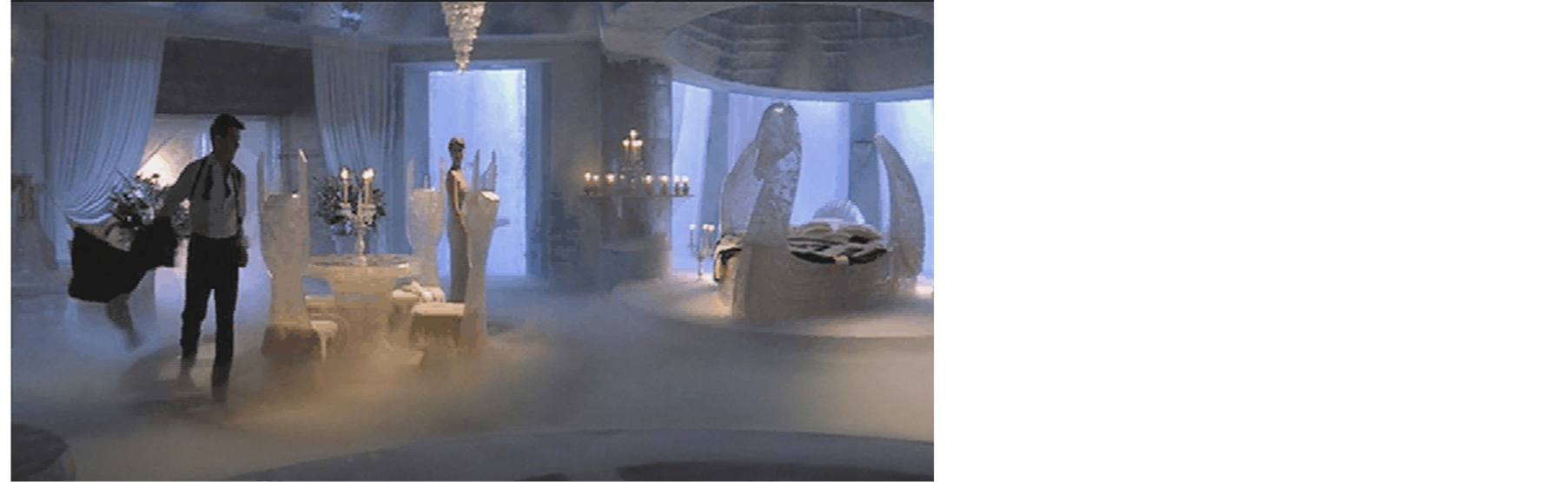

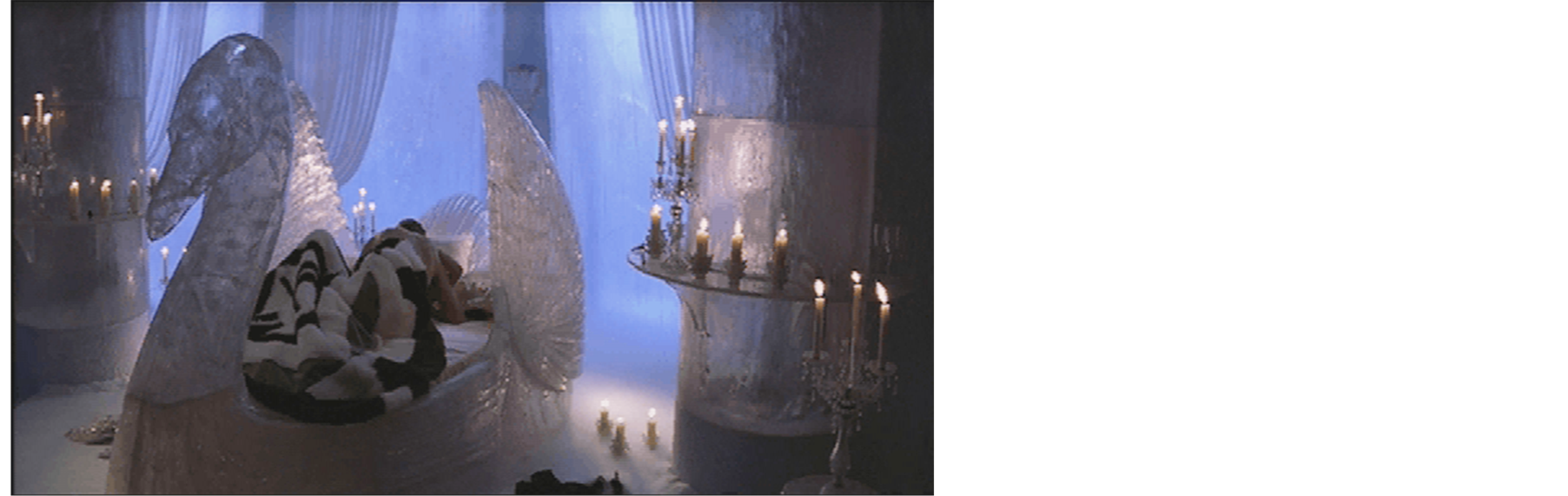

A more recent Bond girl, Miranda Frost forms a rather complex relationship with 007 in Die Another Day (2002); this complexity is defined as two secret agents attempt to seduce each other at the same time (Figure 5). A memorable scene is created when their attempts are proven successful, and they spend a night together in an ice castle. What makes this a mutual seduction? They have agreed to keep up the “charade of being lovers” with the aid of a room equipped with a swan-shaped bed of ice, fur blankets, pools of light, fog, and a few sentimental candles. They enter the room at the same time, which is important in a seduction scene because it implies that one person does not do the tempting, and one person does not have to surrender (Figure 6). Neither individual has the chance to construct a set-up in the bedroom, where they delicately undress themselves—not each other— and almost immediately begin their charades in the inimitable swan bed. Love, light, intuition and grace are the attributes usually connected to the image of a swan, but this seduction is not usual. The scene is better represented when we use the symbolism in alchemy, where the swan is neither masculine nor feminine; rather, the swan stands for “a marriage of the opposites”. Appropriately, the swan bed room is filled with opposites: black and white, fire and ice, rough and smooth, warm and cold. This architectural clashing of elements is reflected in the intentions of these two “lovers”, each trying to extract information from the other while keeping his or her identity hidden (Figure 7).

Even though this is a mutual seduction, Miranda appears to have more control than her counterpart because she seizes power in delicate, almost unnoticeable ways. As mentioned before, the two agents enter the room simultaneously and follow an identical pattern of allurement; the pattern is broken when an undressed Miranda slips under the covers and lies in bed first, waiting for Bond. Until this moment there existed the possibility of

Figure 5. Miranda Frost (Rosamund Pike) in Die Another Day. Dir Lee Tamahori. Perf. Pierce Brosnan, Halle Berry and Rosamund Pike. Eon Production 2002. Film.

Figure 6. Miranda Frost (Rosamund Pike) and James Bond (Pierce Brosnan) in Die Another Day. Dir Lee Tamahori. Perf. Pierce Brosnan, Halle Berry and Rosamund Pike. Eon Production 2002. Film.

Figure 7. Miranda Frost (Rosamund Pike) and James Bond (Pierce Brosnan) in Die Another Day. Dir Lee Tamahori. Perf. Pierce Brosnan, Halle Berry and Rosamund Pike. Eon Production 2002. Film.

refusal. By positioning herself on the bed, Miranda closes any window of doubt as Bond will not say no to a nude woman in a luxurious bed, and she knows this about him. Miranda cleverly handles her actions in the ice castle so that she appears to be someone she is not: in the morning she looks especially concerned, never leaving the bed and grasping the sheets as if they were a replacement for her comforter, who is getting dressed to leave. Miranda is distinctive as a Bond girl, however, for her almost undetectable sense of control over space in the situation of a mutual seduction.

5. Conclusion

Seduction is almost always impure in intent, and one may suspect that the one who initiates the action has some sort of authority which his or her counterpart does not (El-Dahdah, 2002). Most audiences dismiss these seduction scenes as mere plot—instances of lust that somehow have time to happen before the world is saved—however, these seduction scenes show how space can be used to one’s advantage and how one can use architecture in an empowering way—not just to get satisfaction, but to gain control. This deed may be villainous in intent but at the same time it is much too human to be considered malicious.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the analyses and contributions of Katie Nguyen, designer at Melander Architects, Inc. Some of the arguments above were based on ideas first presented at Architecture for the 21th Century Conference at Louisiana State University.