Comparative Study of Inulin Extracts from Dahlia, Yam, and Gembili Tubers as Prebiotic ()

1. Introduction

Currently the addition of prebiotics in food has been carried out. It is based on the ability of prebiotic to support the growth of probiotic in the human digestive system and it provides health effects to those who consume. Inulin is a carbohydrate that serves as an effective prebiotic. Prebiotic is defined as a component of food that cannot be digested by the digestive enzymes that reach the colon without changing the structure and can selectively stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract [1]. Inulin is a polymer of fructose units connected by β chain [1,2] fruktofuranosida preceded by a single molecule of glucose [2]. Inulin glycosidic bond cannot be hydrolyzed by enzymes present in the digestive system, but can be fermented by the microflora in the digestive tract (probiotic). Inulin may enhance the growth of probiotic (Bifidobacterium, L. casei, L. plantarum), and can inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria such as E. coli and Clostridia [3].

In foreign countries such as America and Britain, inulin can be commercially produced from chicory root plants (Cichorium intybus). In Indonesia, the sources of insulin are found in many plants such gembili tubers (Dioscorea esculenta) and yam tubers (Pachyrhizus erosus). As a food ingredient, inulin has a high tolerance for human consumption that is safe and does not cause side effects [4]. Inulin derived from chicory, dahlia and artichoke are classified as food or natural ingredients that are safe according to USFDA GRAS additives instead. Research on probiotic growth in medium containing inulin extract obtained from a variety of tuber (dahlia tubers, gembili tubers and yam tubers) needed to obtain information ability inulin as a prebiotic from various tubers. Several types of tubers are testing the ability of prebiotics on probiotic bacteria L. casei and L. plantarum. Results from this study are expected to provide information about the source of prebiotic inulin and ability as prebiotic.

2. Methods

Gembili tuber (Dioscorea esculenta) obtained from Crops Research Centers Malang, Dahlia (Dahlia L. spp.) obtained from Bumiaji Malang, and yam tubers (Pachyrhizus erosus) obtained from the Great Market Malang. Culture of L. plantarum and L. casei obtained from Microbiology Laboratory, Brawijaya University, MRSA, MRSB, 80% ethanol, distilled water, buffer pH 4 and pH 7, the solution concentrated H2SO4, K2SO4, anthrone, Na-oxalate, Pb-acetate. Inulin standard, 1.5% cysteine, carbazole 0.12%, Commercial inulin (chicory) brand of Fibruline® Instant. The study uses a randomized block design (RBD) by using 2 factors: the type isolates (A) and type of inulin from the tubers (K) with three replications. Factor I: Isolates with type 2 level: A1: L. casei A2: L. plantarum, Factor II: Types of inulin sources with 5 levels: K1: Inulin from Dahlia tuber, K2: Inulin from YAM tuber, K3: Inulin from Gembili tuber, K4: Commercial inulin (Chicory) K5: Without inulin.

Preparation of Extract Inulin

Fresh tuber sorted then washed and size reduction. Furthermore tuber weighed and blended with added water (1:4) to obtain slury. Slury is heated for 30 minutes 80˚C and then cooled. Filtering performed using filter cloth. Filtrate was added 80% ethanol as much as 40% of the total volume of filtrate. Furthermore allowed to stand for 18 hours in a freezer (−10˚C temperature), thawing at ±2 hours, then centrifuged speed 5000 rpm for 15 minutes to obtain a precipitate. Sediment inulin) was taken and dried in an oven cabinet at a temperature of 60˚C ± 6˚C. Inulin Content Analysis: Preparation of standard curve by preparing standard inulin solution containing 20 mg/ml, 40 mg/ml, 60 mg/ml, 80 mg/ml and 100 mg/ml. Each concentration was taken as 1 ml, then added 0.2 ml of 1.5% cysteine and 6 ml of 70% H2SO4, and the mixture shaken 0.12 plus 0.2% carbazole in ethanol solution. The solution is heated at a temperature of 60˚C for 10 minutes once cool absorbance measured at a wavelength of 560 nm. Figure absorbance (on the Y axis) vs. (concentration X axis). Inulin powder is taken one gram cysteine plus 0.2 ml 1.5% and 6 ml of 70% H2SO4, and the mixture shaken 0.12 plus 0.2% carbazole in ethanol solution. The solution is heated at a temperature of 60˚C for 10 minutes. Once cool absorbance measured at a wavelength of 560 nm, ability of inulin as Prebiotic MRS broth supplemented with inulin powder (9:1 (w/w)) and then dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. Further sterilization temperature 121˚C for 15 minutes, and then inoculated with isolate L. casei and L. plantarum by 2% (v/v). Before incubating, conducted initial analysis includes: total LAB, pH, total sugars, and total acid. Then they are incubated at 37˚C, for 36 hours. After incubation performed the final analysis covering: LAB [5], pH [6], total acid and total sugar [7].

3. Results and Discussion

Tabel 1 showed the characteristics of extract inulin from

Table 1. Analysis of inulin component from 3 types of tubers.

dahlia tubers, yam tubers, and gembili tubers.

The highest value of inulin is dahlia tubers. Fiber content is associated with higher levels of inulin. Fiber called fructan which is a polysaccharide that is built by the monomer units of fructose through β-bond 2-1 fruktofuransida preceded by a molecule of glucose [1], presumably the higher the fiber, the higher ability as a prebiotic. Inulin solubility ranges between 96.51% - 99.02%, which indicates that inulin has a high ability to dissolve in water. Test the ability of the prebiotic inulin of different types of tubers made by adding inulin in the medium and sterilized MRS broth, then added with a starter probiotic bacteria L. casei and L. plantarum. Fermentation was carried out for 36 hours to determine the effect of the addition of inulin on the growth of probiotic bacteria. Microbiological and chemical analysis was conducted on the total LAB, total acid, total sugars, and the degree of acidity (pH) at the 0, 12, 24, and 36 hours. Addition of inulin from different types of tubers into the fermentation medium affects the growth of probiotic isolates (Figures 1 and 2).

Fermentation medium with the addition of different types of tubers tend to increase the total number of LAB during the fermentation. The addition of inulin stimulates the growth of LAB significantly. Inulin can selectively stimulate the growth and activity of probiotic bacteria [8]. This is presumably because the lactic acid bacteria utilize inulin as nutrients for growth. Inulin extract as much as 40 mg/g of fermentation medium can significantly enhance the growth LAB compared to the medium without the addition of inulin ([9], in the large intestine almost all inulin is fermented into acids short chain fatty acids and some specific microflora producing lactic acid [10].

The highest increase in total LAB isolate L. plantarum found in the media with the addition of inulin from dahlia tubers in the amount of 2.80 × 1010 cfu/ml, whereas the increase in total LAB isolates of L. plantarum on media with the addition of inulin from yam tubers and tubers gembili of 2.67 × 1010 cfu/ml and 2.69 × 1010 cfu/ml. It is associated with high levels of inulin contained in each type of bulb. In the dahlia tuber inulin levels obtained values of 78.21%, 48.66% yam tubers, and tubers gembili 67.66%. The increase of total LAB isolates of L. plantarum on media with the addition of inulin from different

Figure 1. The effect of inulin addition from different types of tubers into the fermentation medium on total L. plantarum during fermentation.

Figure 2. The effect of inulin addition from different types of tubers into the fermentation medium on total L. casei during fermentation.

types of tubers according to the value of inulin levels produced in each type of bulb, as alleged by the higher content of inulin as a prebiotic ingredient that ability is also higher. Total LAB on the fermentation of inulin medium yam tubers had the highest increase in the growth of L. casei in the amount of 2.80 × 1010 cfu/ml. An increasing number of L. casei the lowest was in the media with the addition of inulin from dahlia tubers in the amount of 1.62 × 1010 cfu/ml. It is inversely proportional to the increase in the number of L. plantarum on media with the addition of inulin from dahlia tubers. This is presumably because all microbes have specific enzymes that have the ability to break prebiotic compounds, so it is possible to isolate L. casei inulin from the tubers of yam easier to be broken down and used as a source of energy to multiply and cell metabolism. The growth of microbes is a collection of enzymatic reactions [11]. Different microbial species can produce different enzymes working for the same reaction, so that microbial strains are most active in producing a certain enzyme can be selected [12]. The properties of the enzyme produced by a microbe are also influenced by environmental conditions. The high production of enzymes that are not always in line with the amount of biomass produced [13].

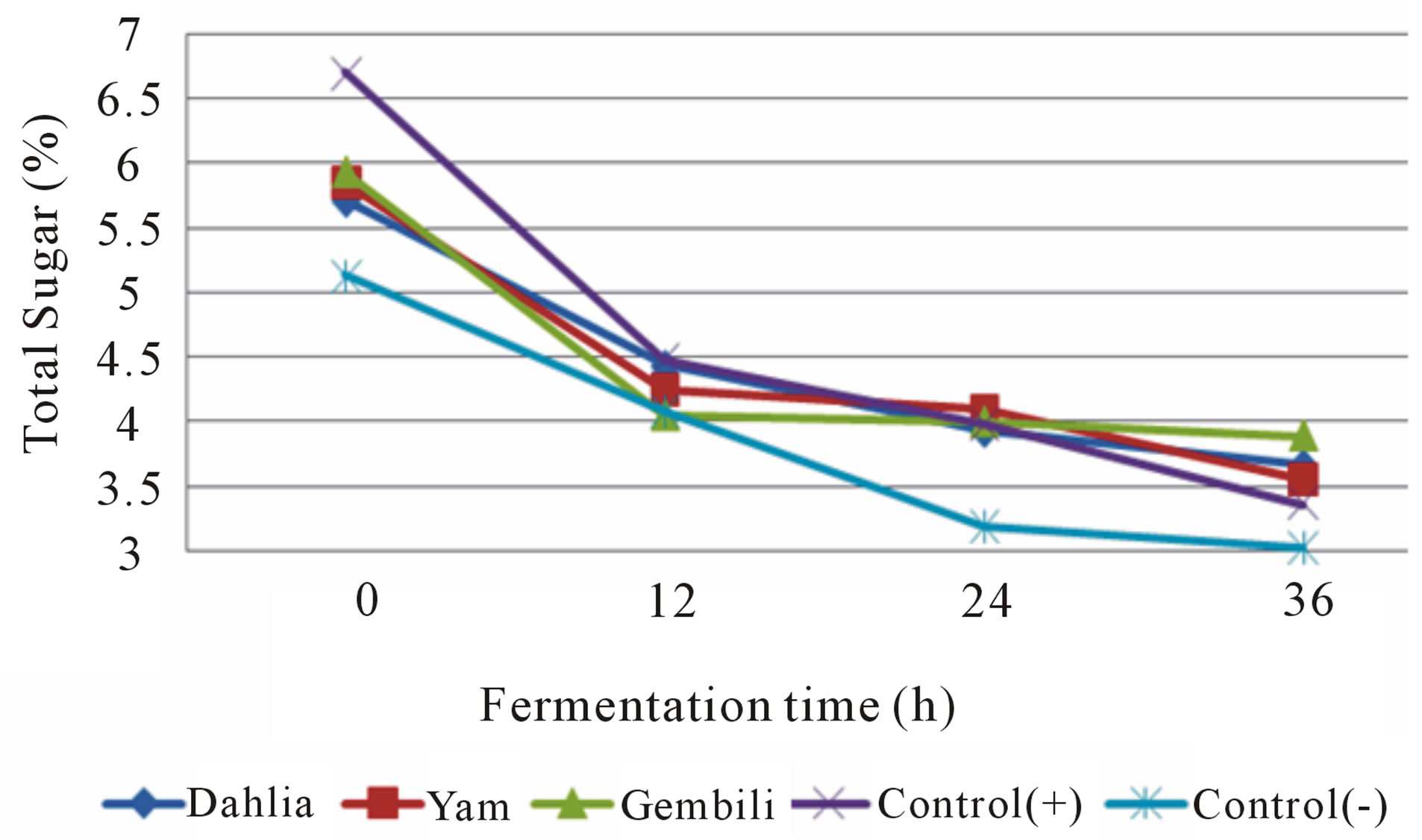

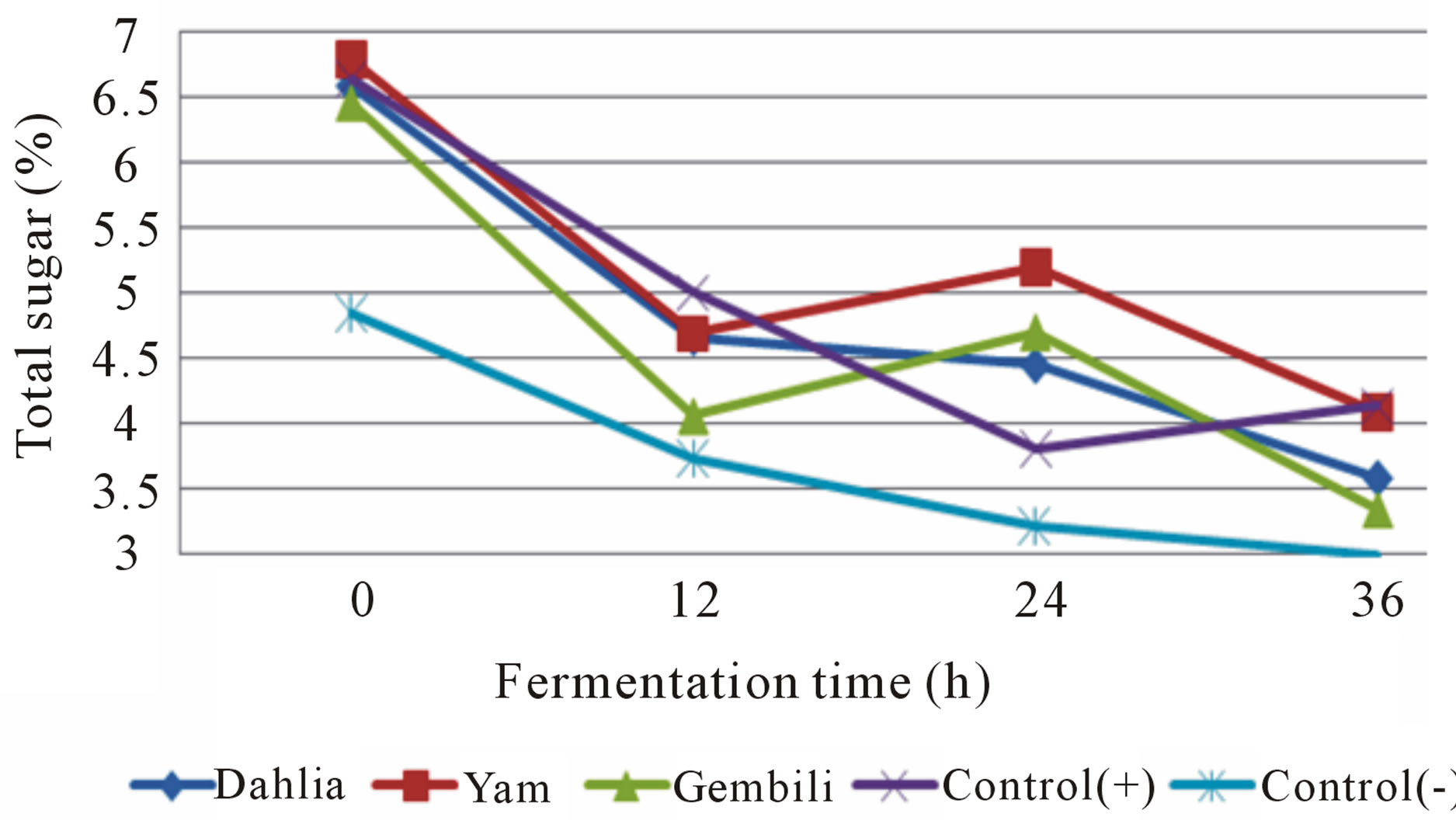

During fermentation process, each of the fermentation medium supplemented with inulin in both isolates caused a decrease in total sugars (Figures 3 and 4). The decrease is a result of the total sugar utilization of the nutrients in both fermentation media. Total sugar before fermentation medium supplemented with inulin higher than without the addition of inulin. Inulin powder contains 6% - 10% glucose, fructose, and sucrose [14]. The higher growth of L. casei and L. plantarum, the lower total sugar in the medium. Inulin can increase the growth of L. plantarum and L. casei [3]. It can conclude that inulin can act as prebiotic.

During fermentation lactic acid bacteria metabolic process that produces lactic acid as measured by total acidity (Figures 5 and 6).

Total acidity increased during fermentation. This is due to the accumulation of acid produced during the fermentation progresses. The mean total initial acid (h-0) on each type of media and type of isolates ranged from 0.33 to 0.54%. While the average total fermentation acids ranged from 1.14 to 1.95%. The increase in total acid fermented inulin fermentation media isolates L. casei increased to 1.50% higher than the isolates fermented

Figure 3. The effect of inulin addition from different types of tubers on total sugar medium during fermentation (fermented by L. plantarum).

Figure 4. The effect of inulin addition from different types of tubers on total sugar medium during fermentation (fermented by L. casei).

Figure 5. Effect addition of inulin from different types of tubers on total acidity in medium fermented by L. plantarum.

Figure 6. Effect addition of inulin from different types of tubers on total acidity in medium fermented by L. casei.

inulin fermentation media L. plantarum. This is related to the ability of isolates to utilize the nutrients contained in each of media and presumably because the total number of LAB L. casei during fermentation is higher than L. plantarum so it has more ability to hydrolyze substrates to lactic acid were measured as total acid. Fermentation L. casei included in lactic acid bacteria heterofermentatif facultative [15], and are included in the sub-genera streptobacteria which is able to produce lactic acid and 1.5% at the optimum conditions [5]. The highest increase in total acid obtained in the fermentation medium with the addition of inulin treatment of tuber gembili, i.e. 1.34%. It is hypothesized that the addition of inulin fermentation media from gembili tubers are preferred by the bacterium L. casei and L. plantarum thereby increasing both growth. The high number of bacteria affects the increased lactic acid produced. In this case the activity of the bacteria L. casei and L. plantarum which metabolize the nutrients in the medium gembili inulin from tubers that produce lactic acid in the intervening 36 hours, resulting in the accumulation of lactic acid during fermentation and result in an increase to total acid.

Determining the best treatment using multiple attributes [16]. The parameters used were total LAB, total sugars, total acids and pH on bacterial L. casei and L. plantarum. The best treatment is to isolate L. casei obtained in the fermentation medium with the addition of inulin gembili tubers, While the isolates L. plantarum the best treatment fermentation media with the addition of inulin from dahlia tubers.

4. Conclusion

The addition of inulin extracted from dahlia tubers, yam tubers and tubers gembili affects the increase in the total number of LAB in both types of isolates (L. casei and L. plantarum). The best treatment with the isolate L. casei was obtained in the fermentation medium with the addition of inulin gembili tubers with the following characteristics: total LAB reached 2.71 × 1010 cfu/ml, 1.50% total acid, pH 2.05 and 3.11% total sugars. While isolateing, L. plantarum best treat fermentation media with the addition of inulin from dahlia tubers with the following characteristics: total LAB reached 2.80 × 1010 cfu/ml, 1.29% total acid, 2.24 and 2.05% total sugars.