The Concept of Parenthood and Parental Care Dynamics among the Dagara in Ghana ()

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The dependency status of an infant requires that it must be in the custody, care and control of one or more responsible adults, capable of assisting in the successful integration of the child into the society through nurturing and education. Parents traditionally perform the primary role of providing the care, maintenance and protection that the child needs before reaching adulthood. The mother in the real context is usually the main caregiver for the infant, but in the typical compound households, grandparents, siblings, fathers, other families, and non-family members often also contribute to childcare. However, these traditional caring practices and arrangements have been altered or eroded among the Dagaaba in the Upper West region of Ghana, often for the worse as a result of labour migration, inroads of the cash economy, and land exhaustion (Baataar, 2010) [1] .

More importantly, the involvement of the older relatives in the marriage process and the acceptance of the younger folk also compel the elders to exert all their energy morally and otherwise in supporting the marriage of their youngsters and seeing them through their difficult times. They were traditionally in a position to monitor, predict and resolve relations that were conflictual and could easily break apart. This prevented or curtailed conjugal conflict, the shirking of parental responsibilities and helped maintain marriages (Baataar 2005) [2] .

The picture of an unhealthy mother holding the hand of a child with a distended stomach has become the symbol of the incapacity to care adequately for children in some communities in Upper West Region (Baataar, 2010) [1] . This problem could be attributed to certain social and economic changes in society. A generation ago individuals even if they did not share the same household or eat from the same pot, were still bonded mainly by ties of economic and social dependence and inter-dependence, and governed by some norms and morals and linked by ties of kinship, affinity and common descent. They thus developed a sense of belonging. In the event of loss of one’s parents for instance the members of the lineage―yir dem―parents, siblings, classificatory parents and other kin, especially grandparents took up the responsibility of the upkeep of the child.

However, the Dagaaba systems of kinship, marriage, and domestic organization today, are undergoing some kind of social metamorphosis. The processes of migration and urbanization have weakened the bonds that kept members in close interaction with each other. Therefore, social values embedded in social welfare, economic welfare, housing and other social facilities available to members of the family are waning, giving way to the formation of nuclear unions (husband, wife and children) with entirely different characteristics.

The situation is compounded by the fact that in modern times the stability of domestic groups has been seriously threatened. Marriage has gradually become the individual’s concern rather than a concern of two lineages, i.e. those of the married couple. Emphasis on individual mate selection without the active involvement of the lineage members has tended to cause marital instability among the Dagaaba (Baataar 2005 [2] ; Banungwiiri, 2021 [3] ).

In the urban areas, the housewife’s tasks may be monotonous and never-ending but they are not comparable to the burdens of the village or rural woman, who has to carry water, find and transport wood and spend hours each day on basic food processing. In all these situations, the infants are the most vulnerable.

It should be noted that adequate parenting has increasingly been recognized as an important predictor for the outcomes of the offspring. Warm and supportive parenting is repeatedly credited for its association with children’s higher educational achievements, better psychosocial development and lower rate of deviant behaviour (Baumrind 1991) [4] . This is the more reason why the imminent collapse of parental care in the study area is a problem of deep concern. The fact that children are dependent on others for satisfaction of their needs creates an even greater obligation to help and protect them.

1.2. Research Questions

The study seeks to answer the following:

1) How does the Dagara as a people understand the concept of parenthood?

2) What, if any, networks of supportive relationships among kin exist and contribute to childcare?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Solidarity within Family Relationships as a Basic Concept

The frequently asked questions about the general sense of a decline in the strength of family bonds are: Why is it that family bonds are eroding? What is the basis of the supposed strength of family bonds? And what are the implications of a decline in the strength of such bonds?

The key concept often employed in formulating answers to these questions is solidarity. This is defined as “feelings of mutual affinity within family relationships and how these are expressed in behavioural terms” (Mulder, 2000) [5] . This is a multidimensional concept, a number of aspects of which can be distinguished.

The concept focuses on the fact that the unifying force of relationships lies in the willingness of relatives to subordinate their individual interest―in part if not entirely―to collective interests of others in the relationship (Misztal, 1996 [6] ; Van Ooschot & Komter, 1998 [7] ). Van Ooschot and Komter (1998) [7] distinguish four significant motives for expressing solidarity namely:

1) a sense of mutual affection and identification;

2) moral convictions based on cultural transmission [norms and values];

3) considerations of long-term self-interest;

4) accepted authority.

Family relationships will always be based on a combination of these.

Perhaps the importance of a sense of moral duty has declined and the emphasis within family relationships has become more one of mutually reconciling the interests and needs of those in the relationship (Misztal, 1996) [6] . Waerness (1987) [8] puts it that caring is about relations between (at least two) people. She postulates that the person needing care is invaluable to the one providing the care, and sums up that this kind of [informal] care is based on “norms of balanced reciprocity”. But the central question is whether differences in the motives family members have for demonstrating solidarity lead to major differences in the characteristics of family relationships. Solidarity spans various domains. Three types of solidarity are distinguished: instrumental or economic solidarity, social solidarity and emotional solidarity.

Instrumental solidarity concerns how those involved in a relationship express their economic and instrumental bonds. In the case of partner relationship, it might include the division of responsibilities, the formalization of relationship, and the partners’ respective feelings regarding the balance of power within their relationship. In the case of parent-child relationships, it might include arrangements relating to their respective responsibilities, financial matters, and opinions regarding the participation and role of the children in decisions affecting the family. In the case of relationships with kin outside the household, it will include the extent to which practical assistance and care is provided, and ideas concerning the scope the relationship offer for such provision (ibid).

Solidarity can also be used to identify asymmetry within family relationships. It can help determine the degree of stability and reciprocity in terms of the contributions and expectations of those involved. According to Misztal (1996) [6] tensions and rifts can emerge between family members, regarding for example, the provision of help to parents in need, as well as disagreements about the division of responsibilities between partners or resentment on the part of parents who expect much from their children but do not feel they get enough in return. At the network level the concept allows one to consider the relationship between the nuclear family on the one hand and the broader network of family members on the other, and the degree, for instance, of family individualization of kinship networks.

2.2. Kin Support in Childcare

It has often been said that in the days when African societies were more traditional in their ways, women’s situation was not as difficult as it is nowadays because collective responsibility among family members ensured that women were provided with adequate assistance in their various roles. Ironically, in present times, just as women are being given more and more responsibilities to shoulder, women are losing much of the support they could have counted upon in the past (Sempebwa Nagawa 1994) [9] .

2.3. Altering Pattern of Parental Care

Cross-cultural literature on childcare (Levine, 1988 [10] ; Scheper-Hughs 1987 [11] ) reveals that care practices are the visible tip of the iceberg of an evolutionary process through which parents adjust their behaviours to the risks they perceive in the child’s environment, the cultural and economic expectations they have of their children and the skills required by the working conditions they expect their children to encounter as adults. Childcare customs are codified systems of beliefs and practices. These cultural codes evolve as compromise formulas that optimize the probability of accomplishing the parents’ and the society’s multiple long and short-term goals.

Levine et al. (1994) [12] noted that it used to be customary for Gusii mothers in Kenya to return to work in the second year of the baby’s life. New mothers were given time and secluded space to concentrate on the needs of the infant. In some societies in Northern Ghana it is reported that among the Dagomba new mothers in the past customarily returned to their natal home for a time, to concentrate on infant care, while they themselves are also mothered, until the infant is grown and walking (Oppong, 1973) [13] . Some decades ago, a WHO report summarized the situation as one in which the structure of families, the basic units of support and nurture for both children and adults is undergoing rapid evolution in many parts of the world, with extended networks of relatives been lost and traditional patterns of social support weakened (WHO report 1995) [14] .

Five global trends have also been documented: domestic groups and sibling groups have shrunk; the burden on working age parents of supporting dependants’ young and old has increased and the proportion of households with only one resident adult male has grown (Bruce et al. 1995) [15] . Whiles women’s participation in the formal labour market has increased, men’s in contrast has declined. First, traditional family systems are described in which looking after baby was everybody’s job.

Swadener, kabiru and Njenga (2000) [16] explaining some of the changing family patterns, observed that the average age of mothers is lower than it was 10 to 15 years ago. Consequently grandparents were described as younger and busier, meeting their financial needs and less likely to be available for some of the traditional care giving roles.

2.4. The Dagaaba Identity

The Dagaaba inhabit the north-western corner of Ghana and part of the population in Burkina Faso. The term generally used to refer to this group is Dagarti, which is a corruption of the term Dagao or Dagara. The term “Dagarti” has been used by non-natives, but is certainly an anglo-misnomer and not appreciated by most Dagaaba. Dagao means the entire geographical area inhabited by the Dagaaba―the people. When a speaker wants to be emphatic he would normally speak of Dagawie [the total geographical area, inhabited and uninhabited, forming Dagao]. Some confusion exists about the ethnic identity of the Dagaaba. This is largely because of some internal differentiating terminologies used among themselves to refer to various sub-sets of the same totality. The terms used to differentiate these subsets include Lobi, Dagaaba, Dagamiile, Lowiile, Mwelere, and so on. Goody (1967) [17] , who has done fieldwork among the Dagaaba, spent time and effort trying to explain these internal differentiating terminologies. However, when these subgroups want to distinguish themselves either jointly or severally from other ethnic groups such as the Tallensi, the Dagomba, or the Mossi they refer to themselves as Dagaaba or Dagara.

There has been considerable confusion among writers on the Dagara-speaking groups, concerning the terminology of the various sub-groups. According to Goody (1967) [17] , the first British expeditions reaching this area referred to the Birifor as Lobi, and in the earliest Record Book of Wa, the Wiili, the Dagara and the Birifor are placed under the term Lobi. The Dagari of the French were the Lobi of the English, and to the English, the Dagara (Goody, 1967) [17] .

Rattray (1932) [18] seems to have referred to the Birifor as Lobi [he did part of his fieldwork in a Birifor village, Tiole, not far from Kalba] (see Goody 1967) [17] .

According to Lentz, the advent of indigenous intellectuals, a process of creating ethnic unity in the region began. The most common overall term used in this process has been Dagaaba for the people (the “tribe”) and Dagaare for the language [containing various dialects]. Among these writers are Kuukure (1985) [19] and Bodomo (1997) [20] . Lentz had noted that in north western Ghana, Dagara inhabit the area surrounding the town of Nandom, Dagaaba the area of Jirapa, and the Birifor the area of Tuna-Kalba [western Gonja]. She also states that there are no Lobi in Ghana which is not quite correct], Lentz also rejects an overall “blanket-term” for the people, stating that they never use one themselves (Yelpaala, 1983) [21] .

However, the common understanding today is that the term Dagaaba is the overall term used by the people themselves, and the language is Dagaare. Bodomo (1997) [20] , outlines four main dialects of Dagaare in North-west Ghana:

・ Northern Dagaare (Dagara), spoken in the Nandom and Lawra area;

・ Central Dagaare (Dagaba), spoken in the Jirapa and Nadawli area;

・ Southern Dagaare (Wala), of Wa and Kaleo area;

・ Western Dagaare (Birifor) of Sawla-Tuna-Kalba area.

Thus, it has become clear that considerable contradictions and much confusion has characterised the efforts of different writers in their attempt to agree on what to call these people.

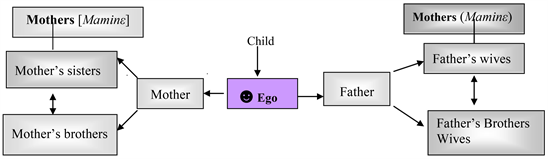

As shown in Figure 1, children born to a patrilineage are called yir biir (house children) and consider themselves to be related by blood because they all received the same blood from the same real ancestor. These call the physical and social house their saa yir (father’s house) and are intimately related to all living in the house in direct and collateral line. Hence to a child: all males saakomine (grandfather), or saamine (father), saabile (junior father) or saakpee (senior father) or yebr/yedebr (bothers) or bideb (son). All females (agnates and affiliates) in the patrilineage are either makomine (grandmothers) or mamine (mothers); purmine (aunts of father’s sisters) or yeepuli (sisters), or pogbe (wives) or pogyabe (daughters). In the tradition there are strictly speaking, no “uncles” no “cousins” and half sisters or “half brothers”, no “step fathers” and “step mothers” within the same yir-family. Patrilineal filiations and affiliations are considered to be full in Dagaare common parlance. Women married into the lineage are bie-pogbe (sons’ wives) to their husbands’ mothers (sir-mamine) and fathers (sir-saamine). They are also “wives” to all agnatic brothers and sisters of their husbands, of course without sexual implications. The latter are respectively their “husbands” (sirbe) and “women-husbands” (sir-pogbe). Wives of brothers are yenta-dem or yentabe (co-wives).

We have so far being examining certain pertinent socio-economic and historic settings of the study area, the people and the region as a whole. Our next chapter would now look at the concept of Parenthood―Dogrbε-Fεrυtome―among the Dagaaba; the meaning of parenting, parental practices, roles and responsibilities and how these have changed overtime. The consequences of all these on maternal care giving practices such as feeding―breastfeeding, supplementary feeding, weaning etc.―shall be examined.

3. Methodology

This reseach employed an ethnographic approach (qualitative) to the study. Ethnography originally was used by anthropologists and sociologists to explain unfamiliar cultural practices.

Researchers use ethnography for several different purposes, including the elicitation of cultural knowledge, the holistic analysis of societies, and the understanding of social interactions and meaning-making (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1983) [23] . Traditionally, with ethnography, the focus is on a single setting or group, and is small in scale, hence, my concentration on the Dagaara of Nandom traditional area where respondence was purposively sampled.

3.1. Sampling Techniques

The sample was purposively selected. This because I have prior knowledge about the study area and this enabled me to accurately choose and approach eligible participants purposively. Sometimes, some people were also recommended as persons who would be “better to talk to” about Dagaaba traditional parenthood and care practices and so forth. Key informant and in-depth interviews were also undertaken with community elders, grandmothers, grandfathers/mothers-in-law, in the study area.

![]()

Figure 1. Dagaaba family structure. Source: Suom-Dery 2001 [22] .

3.2. Data Collection

The study employed mainly a qualitative-ethnographic research approaches. The Data collection included key informant interviews, semi structured and in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with some mothers and fathers. All the interviews were conducted in the local language, Dagaare, with the illiterates but English with the literates. Data were recorded on an audio recorder after the people were assured that this was only to ensure that no important details were left out.

The focus group discussion focused on their views on childcare and their perceptions of changes in these practices over time. They were asked to recount who served as caregivers (primary, supplemental, or surrogate) for children when they (the interviewees) were young; in what ways (if any) caregiving patterns have changed over time, and to what they attribute these changes.

4. Findings and Discussions

A key Informant (Grandfather), during an interview session said:

“Parenthood among the Dagaaba is unique. In the olden days when the extended family system was the norm, parents could include even the grandfathers and grandmothers and come down to the immediate fathers and mothers. With changes in living arrangement and relationship, where people have the interest to separate and live individually, parenthood is reduced to include only the biological parents of a child. Thus, parenthood today refers to a couple who takes the responsibilities to bring forth children, nurture and nurse them up to become responsible human beings in future” (Key Informant, 2022).

In order to understand the present, one needs to explore the past and the dynamics thereafter. The history of parenthood is inseparable from the history of the family. Historians and anthropologists continue to debate whether families based on emotional ties replaced those based on material interests and, if so, when. Some scholars point out differences between families in past times and contemporary families. Half a century ago, Philippe Ariès (1966) [24] , in his Centuries of Childhood hypothesized that modern ideals of liberalism led to a new conception of childhood and, by reflection, of parenthood. The analysis in this discussion here is a synthesized collection of life histories and discourses, views and understanding of elderly Dagaaba men and women including narratives.

This is important because according to Combs-Orme and Cain (2006) [25] an understanding of “poor” parenting from the perspective of the range of parenting tasks children require for healthy development would provide information that would be helpful not only in understanding parenting problems, but also in designing and delivering effective parenting interventions. Parenthood is often seen as the concerted efforts by a couple to take proper care of their offspring. Here, we are dealing with the roles (rights, duties, responsibilities) and statuses that are attached to men called fathers and to women as mothers as well as the discursive terrain around good and bad fathers. If fathers are seen in relational terms to mothers and children as elements of social structure, fatherhood can be seen as the cultural coding of men as fathers (Jouko Huttunen 2006) [26] . Undeniably, parental support and encouragement pave the way to producing successful children.

Contextually parenthood among the Dagaaba is seen to be processual. It is both biological and social. Contextually even minors’ or siblings’ caretaking is sometimes seen as parenthood. For instance, if a minor in the absence of both parents or otherwise, solely take up the responsibilities and duties as such then we would say he or she is the father and the mother known in Dagaare as ulle ni a saa ne a ma. Such a minor is often openly praised and a referent point for corrections of deviant or weird minors in the community. He has no kind! (O tosob be kabe!), they would often say.

From my interaction with my respondence, biological parenthood within the context we are discussing among the Dagaaba has to do with marriage, childbearing, child nurturing and childrearing. According to the Dagaaba social prescriptions/norms require that to be a parent one must be of age, properly married and this goes with maturity. Child birth before and out of marriage was and remains illegitimate and abhorred. Parenthood in this and other connotations has therefore to do with personhood. It was not just enough to give birth to so many children and be expected to be called a father or a mother. As a rule, every man had a fundamental obligation to look after his wife and children. Failure to discharge this obligation drew shame upon the kin members and the whole community. The (extended) kin-group promoted the ideal of responsible parenthood, and strong traditional or customary sanctions were used against those individuals who did not uphold the ideal. Even more strongly, combined with the communal aspect of life, the community bore an overwhelmingly protective responsibility over its lesser individuals.

Now many couples are producing children without regard to their ability to provide for them adequately as confirmed in my interviews. Furthermore, the delay in marriage which accompanied the need to accumulate resources (including experience and guidance) no longer act as a constraining influence, and many people now marry (or rather co habit) at younger ages.

4.1. The Dagara Concept of Fatherhood (Saanu)

From a conversation with the elderly; “A father is simply the head of the household. He is married, has children and there is a cordial relationship between him and the wife.” (61 year old Key Informant, 2022). He further explained that among the Dagaaba, the term father (saa) is broad. A father could be one of the following persons:

・ Any elderly person within a particular compound or kingroup.

・ The biological father of the child/children.

・ Agnatic sibling of the biological father. In this case, the junior brother (sããbile) or the senior brother (sããkpεε), age does not matter (Key Infromant, 2022).

Today however, a father, among the Dagaaba, must have a direct genealogical link to a child. In most cases, he is the biological father. This view was not very different from the views of women. According to the women, two things are considered before the title father is given to a man.

n Must be married and have a child or children or

n Any person who is providing certain needs―food, shelter, health and protection―to children.

They added that in the olden days, men took it a pride to bring their sisters’ children to their homes and brought them up. In that process, they became fathers. However, much respect is given to men who are married and brought forth children and take care of them very well.

Consequently, the term “father”, becomes applicable to someone (a man] who has begotten a child (whether or not he is married to the woman) and takes up the responsibility to provide all the necessary needs of the child. By way of assuming such responsibilities, the person is a father and therefore takes on the status of fatherhood.

A key informant aged 61, added a slightly different perspective of fatherhood.

“In the past, a child did not point out one man as his/her father. Even people who did not provide such care and protection, were “fathers” once they were elders, both within and outside the extended kin relation. Nonetheless, the biological father (saa dogra) was seen as a god within the nuclear family. Whatever came out of his mouth was taken very seriously without questioning. Apart from that, he built up the family and made sure that the family was strong and famous. By this process, he is a father.” (Key Informant, 2022)

This explanation is in line with Baataa (2010) [1] . A fifty-five-year-old man cunningly but dramatically put it that: “Any elderly person can become a father, if he takes up fatherly duties”. That is why in Dagaare, it is often said that―Kpεε mi en sãã. This means that in the absence of a father, any elderly sibling or person in the household or compound becomes the father. By implication a father should be a leader. In a Dagaaba traditional situation, where respect is given to elderly men, any elderly man is designated a father based on his experience, responsibilities and commitment. For instance, in cases where a group of agnatic brothers―yir yεbr―split to build new houses or domestic dwellings, adjacent brothers irrespective of whether full or half siblings, become fathers to their own and their brother’s children. The Diagram 1 below illustrates this.

Diagram 1. Agnatic brothers and their relationship to their children. (Source: This study, 2022).

From the diagram, Ayuo and Ziem are the parents to A1, B1, C1, and D1. The latter also begot A21 and A22, B21 and B22, C21 and C22 and D21 and D22. In each sibling line, they become fathers to the children they begot irrespective of the level of genealogical proximity.

Consequently, the term father among the Dagaaba is classificatory (sometimes becomes generic) and a show of respect is due to the person being so addressed.

However, in recent times, any young man assumes fatherhood status by virtue of begetting a child, whether he takes up responsibilities for the child or not. Similarly, children make a distinction to their biological fathers as their fathers, but not anybody else, not even the father’s brothers or sisters.

As noted in other ethnographic literature in Africa about fatherhood (Nsamenang, 1987a) [27] , a focuse group said: “a typical Dagaaba father also exerts considerable influence and wields enormous control over the resources and is expected to control what happen within the household, to the extent of deciding whether or not his wife or children should engage in activities outside the home. The implication of this is great with regard to resource and childcare. A father’s position in the community largely determines also the social status and lifestyle of his family. The traditional father filters societal values and expectations to the family by ‘covering’ members of his family and acting ‘in spatial and social realms outside the kitchen’ of his wife He is also the one person who sets and enforces standards of behavior and controls family decision-making, including filial marital choices. The father assumes a crucial role in problem solving and protection of the family by exercising a moderating influence on family interactions with the external world. He is expected to be the first person to be consulted or informed of any trouble or major change in a child’s life. He can, and often does, call on his children for assistance at any time and can even intervene, without being seen to be intruding, in the affairs of a married child, particularly his son” (Focused group discusion, 2022). This submision is in line with Nsamenang (1992a) [28] and Feldman-Savelsberg (1994) [29] . The cultural image of the father is therefore that of an esteemed member of the society; the acknowledged head and focal authority of the family. A true reflection of this is that among the Dagaaba one remains a child [regardless age and status] before one’s parents. The implication here for this study could be the weight of their influence on the state of mothers and children.

My concluding discussion on fatherhood in the context of the Dagaaba is that the values of parenting are diminishing. Every child had or has a father somewhere, even if the child does not live with its father or sees him very often. Fatherhood should therefore be a social role in addition to the biological. In the western world it is generally accepted that a man becomes a father when he impregnates a woman. This biological criterion of fatherhood is under increasing stress however as indicated by Richter and Morrell (2008) [30] . Some biological fathers do not act like fathers and do not support their children. Asamenang (1987) [27] , said that a man is a father because he has responsibility for a child.

4.2. Concept of Motherhood (Manu)

My discussion about the understanding of motherhood was not very different from that of the male functions of parenthood. However, much emphasis was placed on the mother as a nurturer and caretaker. According to a respondence:

The Dagaaba believe that, “N Kaara la n ma”, (my caretaker is my mother). I per se was brought up by my grandmother―Makuma, thus, she was my mother and I called her mother―Mma (Key Informant, 2022).

This concept of motherhood (one who nurtures and cares for children), is different from the one who has actually given birth to a child. Among the Dagaaba, when you call your biological mother your mother and call her sisters and her co wives (yentaaba) by their names, they would say you are not well trained. All these were people who mattered a lot in your life as a child as far as caretaking was concern. Co wives as well as mother’s sisters were all mothers. Even those who for one or two reasons could not discharge motherly duties were still considered as such. They were only simply irresponsible. They were all your mma, mma kpεε, or mma bile (i.e. mother, senior mother, junior mother respectively). Thus, it was part of the duties of the focal parents to teach their children how to be respectful.

The Dagaaba today, state that this way of life has changed. Family relationship has narrowed down to only mother, father and children (biological, nuclear, conjugal family). This makes the modern child take his mother’s relations less seriously and even address (call) them by their names, a thing that was unheard of in former times. This could attract serious verbal or sometimes physical sanctions because it was disrespectful, for one does not call his/her biological parents by their real names.

A respondent added similar flavour to the motherhood as nurturing:

Among the Dagaaba, a mother is any woman who has the love and care for children. She may be married or not. Such a woman does not discriminate in the care for children. She could be a “yentaa” (a rival ? in this case, sharing a husband). She takes up responsibilities such as; bringing up the children, nursing them to be adults, giving full moral and financial support to the husband, loving and setting good examples for the children to follow, among others. (Key Informant, 2022)

Therefore, if a woman who does not possess any of the above qualities (among the Dagaaba) becomes just a woman and not a mother.

Some others explained it differently. Among the Dagara, there is what is known as Bεlu (maternal relationship). Every child is born into two groups of relations―the paternal (father’s line) patrilineage and the maternal (mother’s line) matrilineage. Each of these plays a major role in bringing up children. Talking about the term “mother”, takes two major dimension; Mother) from the mother’s side) and mother (yenta; rival, co wife). When motherhood designates a biological dimension, the mother side plays a lead role. Motherhood in this case, therefore gives weight to the biological mother and extends to all blood relations of the biological mother―man or a woman. Among the Dagaaba, “madebr” (mother who is a man, man-mother, maternal uncles) especially play a lead role in bringing up children, since they believe they all come from a common line. Consequently, the term “mother” becomes quite inclusive, but much concern is however given to the caring biological mother.

A Traditional Birth Attendant (TBA) among a group made a concluding observation that the concept of mother in the Dagaaba traditional system is quite inclusive. It does not merely refer to the biological mother. In the olden days, two terms were commonly used; ma and makum. While makum (grandmother) was limited to either a person’s parents’ mothers the ma could then cover the person’s mother’s sisters and brothers (all within the mother’s side); plus, all women in the house who are the wives of the person’s biological father’s brothers (all from the father side). See Diagram 2 below.

According to the tradition therefore, all these mothers listed contribute significantly to the upbringing of a child, but the biological mother played a lead role. In most cases, people even nickname the mother after her first born; eg. Ayuoma, (Ayuo’s mother) etc.

From the above point of view about Dagaaba “motherhood”, the term mother becomes loosely defined, but could be summarized as a woman who takes certain responsibilities by way of nursing or caring for children.

Diagram 2. Mothers related to the dagaaba child.

4.3. Changes in Parenting among the Dagaaba

Infancy is a sensitive period during which parenting is crucial to healthy development, and inadequate parenting may have serious and long lasting effects for children’s health and development. This section reviews and discusses the essential aspects of parenting infants. I have already discussed what it means to be a parent; mother or father. Can all these compliments be said to be the same today? Who takes up what responsibilities, and at what level? What is the degree of change/neglect? These and other questions are what should be of concern to us now. Literature and research from child development, and child and family studies are highlighted to illustrate what is known about the parenting of infants and current direction of shifts.

It takes a great deal of effort to separate a mother from her newborn infant; by contrast it usually takes a fair amount of effort to get a father to be involved with this (Fukuyama, 1999) [31] .

Much of what is discussed here are views or opinions and narratives from key informants as well as group discussion and general conversations. It is common to hear parents talk about the changing world―zie liebu/sangmu―in which their children are developing. This is a clear demonstration of parents concern about the impact of external forces, such as local and world events on the lives of their children and their futures. Over the years, parents of every generation have reflected on the significant or, at least, evolving differences in attitudes and approaches towards children and parenting.

The very act of having a baby brings the mother/caregiver into the culture in a new way. Bringing a baby into the world is fraught with social consequences. Your status change, and even more to the point, the rights and responsibilities that go with your roles in the society also change (DeLoache & Gottlieb, 2000) [32] . At this point the Dagaaba would refer to such a woman or man as a nir kpee―that is an adult. In this era of competing demands the value of parenting is perceived to have come under so many challenges thus changing the face of parenthood (Coontz 2000) [33] . What are these changing patterns among the Dagaaba?

From the focus group discussion there was a general agreement that the way parents interact with their children have changed considerably. They tried to compare the past with the present. Men are regarded as superfluous in the day-to-day care of new-borns. They often remain remote. This is exemplified by a recorded conversation between two men in the study area.

Mr. A. “The child is crying won’t you go and pick it up?”

Mr. B. “Am I the mother or the baby sitter?”

Mr. A. “It means you don’t pick up your child when it is crying?”

Mr. B. “I only do it when I am free or happy. But do you pick up your child when it is crying? If I begin picking this child now, by the time it starts walking there would be ‘trouble’ for the mother.”

Customarily men/fathers’ responsibilities in the post-partum period were to see that their wives’ confinements ran smoothly with ample food. When their babies become more responsive (12 months and above) fathers could hold and interact with them (probably only in the privacy of their compounds). However when children grow older some men could also carry them on their backs or shoulders publicly in cases of emergencies or sometimes when a couple is returning from farm.

In the past also it was explained that a man was to act as a diviner and healer when his children were ill. These responsibilities emphasized a father’s authority and ritual leadership in the patrilineage. In the past men were responsible for guidance, support and judgment and they remain the teachers and models for their sons. Children must be taught to fear their fathers, since without fear there is no respect for authority. So it is still not uncommon today to see mothers threatening an erring child that the father is coming, in order to stop such a child from misbehaving or disobedience. A child knew from the twinkle in a father’s eye that there was some merit in certain forms of defiance despite harsh reprimands. As children mature, men become less physically affectionate, but their children come to rely on them more.

On feeding, our panelists agreed that every good father should ask about the presence and welfare of his children upon his return from work. During meals time he asks if A, B, or C has eaten before he sets off to eat. If your children have already eaten their share of a meal but demand some of your portion, you should give it to them even if this means you would go hungry. A good father should frequently also ask the mother if there is food to feed the children and if there is not then he gives out the food stuff.

However, things have been observed to be different today. An old axiom was said to be becoming the norm of the day especially in times of food insecurity. A slim/lean baby is beautiful on the back of a well-fed adult. Whereas mothers claimed that fathers no longer provide adequate security to the family. Fathers complained that some mothers had become uncaring, marketing away the bulk of the harvest and squandering the money on clothing. There was a heated argument here, but what it all points to is that there is sale of food stuff from the family harvest. Though the women were rather tight lipped about the sale of food stuff by men, the majority of the women interviewed insisted that;

Men sell out the food stuff immediately after harvest to drink and chase other women and if the wife talks she is beaten. Women are now taking care of men. You yourself (referring to me) as you were coming might have seen the women carrying firewood, charcoal and other things to Wa town to sell to buy guinea corn for the family. Amidst all these sufferings the man would still have sex with the women at night. Because of the prevalence of the HIV/AIDS we cannot refuse them sex even if you are still breastfeeding else they would go outside and bring diseases to us. (Women group, 2022).

Childcare is the adequacy of food stuff at the household levels particularly at certain months of the (June-October) year. Because of the erratic rainfall pattern in the region, there is often poor harvest. But families are forced sometimes under certain circumstances to sell out this little foodstuff for money to meet financial demands or commitments. That, by itself, is not bad in the eyes of both men and women. The basic issue here is what the proceeds of those sales are actually used for. If it is for the welfare of the family there is a consensus. But most often money acquired from the sales of the food stuff is dissipated on alcohol consumption. As part of mitigating such hardship every woman takes up one or two business activities in addition to domestic duties including childcare. But the reality here is that the result is care deficit!

“There are some mothers who wake up very early in the morning, put on their working gears and off to farm while their children are asleep. They do not care to wake the children up before they leave for the farm. Others leave them to their own fate especially during the sheanut picking season. So how will such mothers know what is wrong with the child? When there are people in the house fine, but what happens when everybody is busy, especially in the farming season? Nowadays many mothers are just seeking wealth and do not really care about the welfare of their children, they are just reproducing without love for them.” (A Caretaker Grandmother, 2022).

This observation was about a woman who left home early to pick sheanuts only to return to the village to meet the village people mourning the death of her child. The reason was that she did not find out if the child was well before she left for the bush.

So many issues were raised in other discussions that directly affect the changing nature of parenting. One issue I would term as “internal” has to do with intra familial relations. This has to do with the suspicion of spousal infidelity and alcoholism, both accounting for (resulting in) conflicts. It was said that in the past pito was the only drink among adults. Also, she said in the past, once a woman’s bridewealth was fully paid it was a taboo for her to sleep (have sexual intercourse) with another man. The ramification of that was great and it involved a lot of ritual purification and sanctions on the part of the man in the form of payment for the rite of purification. Today women do that and secretly purify themselves. Some even have the antidotes to the taboo, according to the respondent.

Elders however are tight lipped about divulging these antidotes for public consumption for fear of revolutionary changes in marriage. Increasingly therefore there is no trust in marriages today among couples. The general agreement was therefore that, there are vast differences between marital relations in the olden days and today (recent times). According to a 60 year old grandmother, when they were young and in marriage, there was always constant unity between a husband and the wife, and wives submitted themselves totally to their husbands. Women took instructions and commands from their husbands without question. Women rendered services such as cooking; fetching water for their husbands to bath etc. Here, we do not really think that the woman as a person wholly endorses the fact that, time past, women had to silently or quietly or unquestionably accept male dominance in families. The reasoning here inferred is that women’s acceptance of the male authority or male hegemony kept families intact (though it might not be a happy one).

In times of marital disputes, she said, it was the woman who apologized first to the husband for the misunderstanding caused, regardless of the source. In modern times, some marital disputes are exposed to the public and the disputes are solved either at the chief palace or in the court or police station. She said these are strange things which never happened at their time, these accordingly, are the very elements that are uprooting all the values embedded in the Dagaaba kinship and thereby affecting the way parents take care of their children. It also has to do with the faulty construction of marriages today. There were very interesting answers to a question we asked some of our key informants and group discussants: What are some of the traditional values in marriage among the Dagaaba that are lost and are causing problems in marriages today? What can be done to reverse this situation? Some lost values mentioned included: virginity before marriage, payment of brideprice, investigation into the background of their prospective daughter and son-in-laws, etc.

As it has been documented already, the danger associated with conflictual familial relations increases risks of divorce and separation, domestic disorganization, violence and discord (Oppong 2001) [34] . In these events, it is the children who suffer, as they are often neglected.

Another area of concern is that when parents have chronic and unresolved conflict, children are known to suffer particular stress (Brody & Forehand 1990 [35] ; Buchanan, Maccoby & Dornbusch 1991 [36] ). Parent?child relationships may also be more seriously threatened when the anger or withdrawal engendered by parental conflict is displaced or redirected onto children (Easterbrooks &Emde 1988) [37] . There was a demonstration of this where some men engaged in a discussion remarked that wives who quarrel with their husbands sometimes beat or insult their children on the least provocation, just to compensate for their inability to unleash their aggression on their husbands. For instance, instead of insulting the father by making insultive reference to his disproportionate head, it is to the child’s head that becomes the target of the insultive remark. In worst cases, infants are thrown into the laps of fathers and mother absconds for days.

Inter-generational conflicts and intra family misunderstandings were therefore underlined as contributing to the observed changing parenting. A seemingly resentful grandmother observed that in former times, wives took their parents in-laws as their own parents. This gave an encouragement to grandmothers to lend their helping hand in parental care especially, in the case of the first-time mothers. Today many wives see parents-in-law as enemies of progress and often maintain a state of rivalry with the parents-in-law.

“Some would even devise their own ways of eliminating you or letting your son chase you away or hating to see you. But their relationship (langkpeb) does not even last long after that. In a situation like that you dare not touch the child. Even my grandchildren I have to be very careful with them else their mother who is not directly my child will complain and my son the husband will take me on. So, I simply sit and watch, after all I am only left with a few days to join my ancestors.” (Grandmother, 2022)

The lamentation here of this grandmother is that, generations passed, children were precious to everyone in the community and everybody shared the responsibility of their upbringing―socialization was not the exclusive domain of a child’s parents. This collective or communal responsibility in childcare was widely known and an accepted norm and hence was not seen as an intrusion, unlike today.

A startling revelation was also made by one female key informant on new development in the towns, especially in polygynous homes. She noted that in polygynous homes, wives live in a rivalrous state, each competing with the others for the man’s love; in the process they bleach their skins to be fair in skin to attract the man’s attention instead of focusing on the child or infant care. But what they (referring to the women) fail to know is that all the men are the same these days whether educated or uneducated. They say that as men they can marry many wives and for that matter good grounds for their irresponsibility towards their children particularly a breastfeeding mother. Since he cannot go to bed with you he cares less about you, not until the child is old enough to have another sibling you are at that time his worst enemy. You cannot ask for anything. Women are the sole providers for their infants; the men do as if they are not responsible for the coming of the children.

She also blames women for not taking their time to marry responsible men. They just meet outside and that is all, they are married the next day. This explains the suffering and problem of childcare for women; they (women) are to be blamed.

It seems this message is very important at a time when many men are unable to provide economic support for mothers and children and often pointing hands to unemployment, poverty and limited sources of livelihood. It is widely believed that at least one reason men abandon their children is because of stress, shame, and loss of esteem experienced when they cannot provide financially for their families (Ramphele & Richter, 2005) [30] . Though I did not come across such rivalry or competition in the field, I came across a good case of a polygynous man who stayed aloof and was just a figurative father and husband to the children and his wives.

This illustrates that women often have no choice but to work in the fields and perform daily household tasks, even if the demands on their time threaten the health and nutrition of their children. Across my study areas mothers are sometimes forced to leave the baby at home based on certain considerations.

Because she still breastfeeds if I am going to any place, for example to the funeral, I take her along. If, however, the place is not far or if I would not keep long I leave her with the grandmother or grandfather. (Mother of 33, 2022)

One mother even linked her breast milk inadequacy to her work. Because of her work, she does not have much breast milk. When she is hungry, her child does not get enough milk and he cries.

From the view point of mothers however, it is not bad to have other tasks or duties as these may be sources of income for them to augment their resources for the upkeep of the family and caring for children. The problem inherent here is whether one receives help from other kin members, especially the spouse. According to a mother;

Well, with the combination of a mother’s multiple work, care is not an easy task but it depends on the type of husband one is married to. In my case, my late husband was very supportive; even though I was a pito brewer I combined it conveniently with childcare. He cooked when I was busy. Right from the beginning, he advised me to get more helping hands as workers. They helped me to brew and took turns to brew theirs too. It made my work and childcare very easy and enjoyable. This time round I have a very huge problem, because I am a single parent now, I have to resettle and organize myself properly. Even the present landlord is not prepared to accept my brewing of pito anymore. So I can say it is not easy for me now to combine even office work with childcare. (Educated mother. 2022)

Very few men try to give a helping hand to their wives (especially with domestic work), and if they do their male counterparts may tease them. So, they are normally not willing to assist at all. In terms of the kind of help husbands provided in the post-partum period, mothers reported that sometimes husbands helped with a ride from the village to Wa Regional hospital. Husbands however do not help with household tasks such as cooking and washing. The few men who helped with households’ tasks in the post-partum period were from the educated nuclear families

Conversely a major finding among some illiterate’s mothers is that most mothers consider childcare their own domain and consider husbands as helpers. A mother in the group discussion said that men are rough and inefficient in taking care of babies. “Men do not have breast to feed babies. Babies are delicate but men (including boys) are often rough―not gentle and can give them ruptures.” In this case a man’s parental responsibilities are mainly assessed in terms of financial provisions towards meeting health care costs when the child is sick and material goods such as foodstuff and clothes.

Women living with husbands and children in the town however reported more husbands’ involvement in childcare activities (dressing child, sending child to school on a bike) than those in the village. The reason for this is probably that in traditional Dagaaba society, men’s involvement in childcare and household chores was regarded as shameful because these are purely seen as feminine tasks as indicated by Baataar (2005) [2] . Secondly some fathers found themselves involved in childcare practices because they often live in heterogeneous compounds with no grandparents or direct kin members nearby. There is therefore less help available from other members of the family and community. Those days, baby nurses were being provided by relatives as soon as a woman married and was expecting a baby. Most at times the baby nurse came from the woman’s kin group and when she grew into a mature woman she married into the family of her husband. She was given to either the husband’s senior son (if he had one) or any relation around to maintain that close link. But today even if women’s workload is not increasing it is neither reducing. However getting a baby nurse or babysitter is increasingly very difficult, because many more girls are attending school.

“Even if you go to the remotest village to get a girl who is not attending school to come and help you there is often one very strong condition that is attached; you should send her to school! Then again if you take somebody’s daughter as a baby nurse, all their economic and financial problems would be on you. So, it is better to manage on your own this time” (Mother Nurse 2022).

Today among the Dagaaba it is customary for children of the poor to be given out for fosterage by the well-off. So, to give out your child to another person is to signal your inability to cater for that child.

5. Conclusions

Childcare and education in many societies are organized around family life. The family was and still is the primary institution within which men, women, and children sustain the survival and well-being of members and the society (Nsamenang, 1992a) [28] . This brings into focus the pertinence of Sharp’s (1970) [38] warning against the disruption of the traditional African family that is still the best guarantee of the African child’s welfare and education. This warning becomes more relevant in the face of increasing rather than decreasing levels of abject poverty and inadequate or poorly provided public services. The care and upbringing of infants are generally considered far too important to leave to personal preference.

However, the opportunities to observe and learn about babies through direct observation and imitation have recently been diminished. Cultural practices are being transformed by new situations (DeLoache & Gottlieb, 2006) [39] . From the perspectives of children, all these transformations share one consequence: young parents have fewer opportunities to learn stable traditions from those around them. In bigger towns where Dagaaba couples may live far away from any relatives and in heterogeneous town and compounds with mixed cultures; new parents are often lost as to what to do with childcare. There may be no other mothers, grandmothers or aunts close by to advise a pregnant woman about the birth processes or to tell a new parent what to do when the baby cries or is sick.

6. Recommendations

The study was conducted in with Nandom community. It is recommended that future studies should widen the scope of the study.

It is also advisable to include quantitative data in the area of the number of children playing the role of mother/father, the number of responsible and irresponsible fathers as reported by respondence.