1. Introduction

Kunju, mother of all traditional Chinese operas, is experiencing crisis or challenges in the commercialized and globalized world. Efforts to preserve, protect, and promote Kunju are continuously made by the government and artists. In order to attract more people, young audience in particular, Kunju has been modified or innovated to cater to the tastes or aesthetics of contemporary Chinese. Kunju troupes seek to combine the traditional with the modern in an attempt to restore, revive, and retain the popularity of this classic opera.

Kunju is a well-developed, comprehensive art, and embodies the spirit and aesthetics of traditional Chinese culture. It consists of multiple components, literature, music, melody, dance, makeup, performance, among others. The value of cultural heritage finds itself in the culture it represents. The scripts of Kunju cover various themes throughout Chinese history. The thriving Kunju in the 16th century is attributable to the humanism across China. Kunju originated in Kunshan, a county situated between Shanghai and Suzhou, home to prosperous businesses and intellectual elites. Economic and cultural development contributes to masterpieces, such as The Peony Pavilion,Palace of Longevity,and The Peach Blossom Fan. These plays have been performed from generation to generation.

Kunju is an anthology of Chinese opera. It boasts more than two thousand qupai (tune matrices) from poems, musical modes, mixed drama, nondramatic songs, religious music, folk songs, among others. Another feature of Kunju is the unique performance system characterized by a combination of singing and dancing, music and action. Unlike Western opera, Kunju sees singing and instrumental music as key components of almost all performances. It reflects reality by creating an aura. On the stage, daily utterances turn into poetic words while daily life and expressions turn into dance and performance. Real situations are imitated by settings and gestures. Actor’s personal trait is expressed by makeup, facial painting, and costume. Kunju has long developed norms for performance.

Kunju is the most influential opera during the mid-Ming to mid-Qing Dynasty (1550-1850). It epitomizes the most elegant of literature and the most exquisite of traditional Chinese art form. Kunju is a classic Chinese opera with unique music style. Literally, Kun in Kunju refers to Kunshan, a county of Suzhou, birthplace of Kunju, while qu in Kunqu means music or song that develops from the Kunshan tune refined by renowned musician Wei Liangfu (1522-1572). The term clearly indicates that music plays a key role in Kunju. For example, qupai (tune matrices)1 is an essential component of Kunju.

Historically, Kunju enjoyed unprecedented popularity and wide public participation, popularity that surpassed previous zaju (variety play) and southern opera, as well as various tunes later on. Like in any opera, it synthesizes acting, dance, costume, music, singing, and literature. This synthesis highlights its lasting value and unique charm. In this synthesized art, music plays a fundamental role. It is the soul of Kunju, because it “informs and organizes almost everything that takes place on the traditional Chinese stage” (Li, 2013). In other words, music gives clues about action, plots, atmosphere, characterization, structure, as well as time and space. It serves as a thread stitching all elements into a unity for good stage performance.

Kunju, as part of Chinese cultural heritage, has attracted much academic attention. The existing literature generally falls into five categories: aesthetics (Liu, 1983; Tang, 2016), literary study (Shen, 2000; Zhu, 1996), historical development (Lam, 2019; Li, 2009; Luo, 1997; Xiong, 1994, Yang, 2019), stage performance (Lam, 2014a, 2014b; Lu, 1994; Rebull, 2017; Stenberg, 2015), and music study (Frankel, 1976; Jones, 2014; Schoenberger, 2013; Strassberg, 1976; Xu, 2014). These researches examine Kunju from different perspectives, giving insights into this traditional theatrical genre. This paper examines the youth version of The Peony Pavilion, prodcution that has been widely acclaimed at home and abroad. An aesthetic perspective is taken in the study.

2. Highlights of the Peony Pavilion (Youth Version)

The Peony Pavilion was created by Tang Xianzu (1550-1616), a distinguished playwright in the Ming dynasty. The plot focuses on the power of true love. Du Liniang is the young daughter of a scholar official called Du Bao who hires a good tutor for his daughter. She was led by Chunxiang, Liniang’s maid, into the garden filled with colorful blossoms. Whie sitting in the Peony Pavilion, Liniang falls asleep and has a dream that a handsome young scholar named Liu Mengmei comes to the garden. They fall in love under the tree. Liniang wakes up to find that she is alone though she cannot forget the young scholar. She is lovesick, dies, and is buried in the garden. Sometime later, Liu Mengmei happens to see a portrait of Du Liniang. He recognizes that she is the young girl he fell in love with in a dream. Du Liniang was allowed to return to life and marry Liu Mengmei.

This play is a classic Kunju production with various adaptations from its debut to the present. The youth version of the Peony Pavilion is the latest adaptation, by Bai Xianyong, a mainland-born, US-educated Taiwanese writer. Bai’s version focused on the theme of youth in a bid to attract the young audience.

This adaptation showcased a balance between tradition and change of Kunju in contemporary China. It was widely staged and highly acclaimed in China and beyond. Bai Xianyong took a bold approach to the adaptation with regard to music design, stage arrangement, costume selection, among others. His experimentation or innovation cast light on how to sustain Kunju’s appeal in this commercialized world.

Music is the soul of Kunju, because it “informs and organizes almost everything that takes place on the traditional Chinese stage” (Li, 2013: p. 1). In other words, music gives clues about action, atmosphere, characterization, structure, plot development, as well as time and space. It serves as a common thread stitching all elements into a unity for good stage performance.

The performance tradition of Kunju is characterized by the four skills called chang (singing), nian (recitative), zuo (acting), and da (acrobatics). Chang (singing) tops the four performing techniques, followed by nian (recitative), a kind of musical stage speech. Zuo (acting) and da (acrobatics) are regulated by music for certain rhythmic pattern and dramatic effect. Music is essential to the four skills and achieves a unity in Kunju performance.

Kunju music is more complex and difficult, compared with literary and historical study of this traditional Chinese opera. That is largely because it involves the interactions and interdependency between text (playscript) and music in the framework of qupai (tune matrices)—an essential component of Kunju. Poetic lyrics must follow rules of rhyme, rhythm, and tone, whereas tunes are largely determined by qupai (tune matrices). Since Chinese is a tonal language, words and tones work together to create certain melodic pattern.

Musical aspects determine the success of a Kunju play, as they unify and regulate almost every component of each production. Since the youth version of the Peony Pavilion has been highly praised in China and across the world, it must boast special traits that gain traction with the audience, the youths in particular. In other words, this play meets the aesthetic demands of the youths, as the youth version aimed at the younger generation.

Presentation and appreciation of Kunju, music in particular, is closely related to Chinese aesthetic principles. Vocal delivery features ornamentation or melisma, common practice in Kunju singing. The ornamental style may be difficult for Westerners to understand. But it is one of the key characteristics of Kunju music. Aesthetic demands or principles of Kunju underwent changes while retaining essentials or traditions, things that make Kunju as it was, is, and will be. Once essence or authenticity is lost, Kunju no longer exists. Simply put, Kunju, the Chinese classic opera, has to keep its authenticity intact while innovating to keep pace with the times or Zeitgeitst (the spirit of the time).

3. An Aesthetic Perspective

An aesthetic approach helps advance our understandings of Kunju in general and the youth version of the Peony Pavilion in particular. According to Gamader (2004), aesthetics refers to the dialogue between interpreter and the expression of truth in a particular artwork (pp. 352-353). In terms of Kunju, aesthetics involves the interactions between viewer or audience and the presentation or performance of the play. The Peony Pavilion, a classic play, is still performed with different adaptations in China and other countries like the U.S. The youth version of the Peony Pavilion is the latest adaptation that has been hailed as a good example of Kunju innovation in contemporary China. It was staged widely in China and the U.S., attracting a large group of audience and receiving positive responses from viewers. This youth version aroused the aesthetic consciousness of the audience, who found resonance with this play.

Aesthetic study of the youth version of the Peony Pavilion focuses on aesthetic dimension of the play by investigating music practice of the production. As mentioned above, music is the soul of Kunju. Examination of music practice is more revealing. Aesthetic exploration of this production is intended to identify key features that appeal to the audience, especially the youths. Once aesthetic consciousness is raised (Gamader, 2004: p. 128, 130, 138), the audience would resonate and be obsessed with the youth version. Aesthetic principles of contemporary Chinese should be seen as the root cause underneath the mounting popularity of the youth version. This adaptation was a success, largely because it met the aesthetic preferences of the younger generation.

Aesthetics varied from generation to generation, due to different economic, social, cultural, and political contexts. The Peony Pavilion was created by Tang Xianzu (1550-1616). Tang’s creation was adapted for stage performance in different periods of time. The youth version was the latest attempt, which turned out to be a success. Aesthetic study is concerned with viewers’ perspective to further understand this version’s recipe for success.

While Kunju enjoys a long history and much development, it runs across increasing difficulties in contemporary China. Facing the same challenges as other traditional or classical genre, Kunju is losing its audience thanks to the changing landscape of consumer culture. Globalization intensifies interactions between different economies and cultures. Most Chinese embrace Western consumerism and cultural products while turning away from their traditional culture. Kunju faces challenges from Western popular culture. Though Kunju embodies classical literature, music, dance and stage conventions, it is no rival for electronic music, rock music, or Hollywood movies among youths. Young people are the target and consumers of popular cultural products. These challenges or crises facing Kunju have long been noted by government officials at division of culture, Kunju actors and scholars. They are all keenly aware that Kunju is losing audience and call for innovation to retain its appeal (Zheng, 2003). Given the urgency of preservation, government, scholars, as well as professional and amateur actors should work together to preserve and protect this cultural heritage. Kunju cannot and should not be museum art, and it is expected to expand the size and scale of the audience. In this sense, sheer preservation is inadequate, as innovation is needed to meet the changing ethos of the times.

Facing big challenges, Chinese government has made an all-out effort to protect and promote Kunju as a cultural heritage since 2001 when it was listed among the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. However, government support cannot guarantee Kunju’s popularity if the genre lacks special appeal aesthetically, artistically, and culturally. In response, Kunju composers and performers have made bold experimentation or innovation in a bid to sustain this genre. Thus, Kunju has undergone transformations while trying to retain essentials.

The youth version of the Peony Pavilion is widely accepted as a successful attempt to innovate and revive Kunju in contemporary China. Innovations are made while tradition is best kept. This balance is hard, if not impossible, to strike. These changes are part of tradition in the future. This play demonstrated the boundary of innovation while seeking to preserve essence of this genre. Innovations cannot undermine the authenticity of Kunju. In other words, composers, directors, and performers have limited freedom in their concerted efforts to make changes.

These changes are made in line with contemporary viewers’ taste and preference. Specifically, the audiences’ aesthetic norms should be taken into consideration. Gadamer began his exposition of aesthetics with the concept of play. As he put it, “a drama is a kind of playing that, by its nature, calls for an audience” (Gamader, 2004: p. 109). Kunju emphasizes dramatic effect on stage, generating response and resonance from the audience. Gadamer also stresses the importance of the audience. He maintains that “openness toward the spectator is part of the closedness of the play,” and that “the audience only completes what the play as such is” (Gamader, 2004: p.109). The audience is indispensable to the play. The play, he insists, “appears as presentation for an audience” (Gamader, 2004: p. 109). He argued further that a play[Schauspiel] is even seen as a game, for it has the same closed structure as that of a game. A play is also open to its spectator or viewer who helps the play win its whole significance. Those who watch the play—viewers—enhance the play to its ideality (Gamader, 2004: p. 109). The spectators or viewers play a major role in how a drama or play is presented and received, simply because every drama is open to those who watch it. The audience are absorbed in the play, and take the place of the player. Clearly, only through the appreciation of and interaction with the audience does a particular drama achieve its significance, value, and sustainability.

Only a few literature focused on the aesthetic dimensions in Kunju. Liu (1983) elaborated on the relationship between ornamental styles in Kunju singing and the aesthetic principles or Chinese philosophy underneath such vocal style. Nketia (1984) noted the aesthetic dimension in ethnomusicological studies. The study of aesthetics expands the scope of music research, reaching out to different social and cultural contexts. Tang (2016) investigates the aesthetic philosophy behind the traditions of Chinese Classical Theatre, especially Kunju and Peking Opera. Tang focuses on Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, the three pillars of Chinese philosophy. Good models and less successful examples are given to indicate the traditional aesthetics can either be preserved or lost. The existing literature does not concentrate on a particular piece of production to find out how aesthetics is revealed.

4. Music Design

Music design of the youth version of the Peony Pavilion showcased a balance between tradition and change. This play retained music essentials of Kunju while adding modern music style such as theme music, dance music, and chorus. This music design achieved unity and harmony of music in the play. The music structure created a romantic atmosphere. For example, the theme music for Du Liniang was taken from qupai-zaoluopao (dark silk gown), and the music for Liu Mengmei was adapted from qupai-shantaohong (red mountain peach). The theme music was repeated in performance to reinforce the audience’s impression and perception of Kunju music. This adaptation aimed to attract the young by catering to their aesthetics.

Chorus and polyphony helped make the plots and emotions coherent. The music effect enabled the audience to be absorbed in plot developments. As the younger generation are accustomed to multimedia, arrangement of music should meet their aesthetics in order to boost Kunju’s popularity.

The atmosphere of happy ending, typical of ancient Chinese opera, was achieved through design of musical instruments, duet accompaniment, ensemble, chorus, and duet singing. For example, the two qupai-shuangshengzi and beiwei-were largely altered to move the heart and soul of young people. This successful attempt may pave the way for expanding the viewership of Kunju.

Analysis of one qupai-zaoluopao (dark silk gown) demonstrates correspondence or conformity between text and tune. In this qupai, the lyric was largely in line with melody. In the first phrase-yuanlai chazi yanhong kaibian, lai has yangping (rising) tone. Melody has La and Do. Cha has qu (leaving) tone or falling tone, and the main melody also uses falling notes such as Sol, Re, and Do. Zi is the third tone, starting from high to low and then to high. The musical contour follows Do, La, and Do. Performers often sing La, Sol, and Do, falling and rising tune. The word yanhong has rising tone, and the music notes are Re, Do, Re, and Mi. In Kaibian, bian has qu (leaving) tone, which is represented by Sol, Re, Do, and La. In Scene 9 Sweeping the Garden, the music of qupai-zaoluopao (dark silk gown) features conformity between tone of the text and melodic tune. The correspondence between tone and tune is one of the defining features of Kunju music.

The conformity between text and tune has long been a tradition of Kunju. While following this tradition, some changes were made in composition or aria. Take aria for qupai-dielianhua (butterfly on blossom) as an example. Originally, Qupai-dielianhua (butterfly on blossom) has no notation or music score. In the youth version of the Peony Pavilion, the music score was created in the form of solo and vocal accompaniment. In the beginning, laosheng (old male) sang in a tone reminiscent of historical sentiment.

Chorus for qupai-dielianhua (butterfly on blossom) also revealed changes or recreations. Qupai-dielianhua (butterfly on blossom) was used as the opening song in each of the three parts of the youth version. The phrase “danshixiangsi moxiangfu, mudantingshang sanshenglu” was designed as theme chorus that appeared in the opening and end of different scenes, with different tempos and modes. The recurrence of theme music reinforced audience’s impression and perception, as the audience were more familiar with the melody when the theme music is repeated multiple times.

The last two qupai—Nan shuang sheng zi and Bei wei—in scene fifty-five (Reunion at Court) were adapted to create the atmosphere for reunion. For example, the matric pattern of Bei wei was changed from free beat (散板sanban) to one accented beat plus three unaccented beats (一板三眼yiban sanyan), or duple rhythms of four beat units. The aria ended with actresses’ chorus followed by actors’ chorus, making a happy atmosphere of reunion.

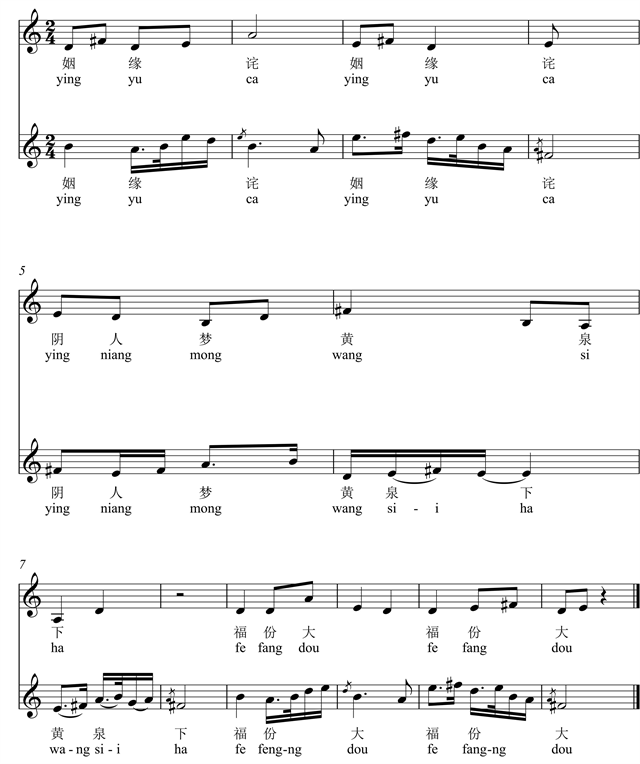

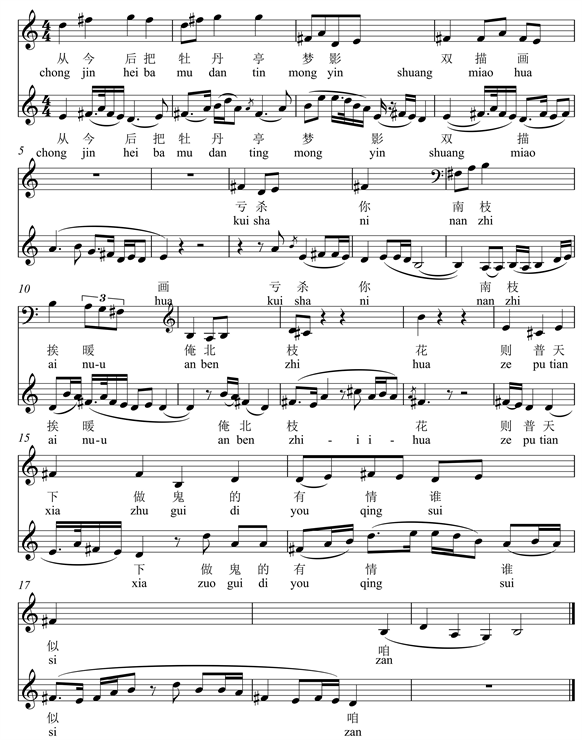

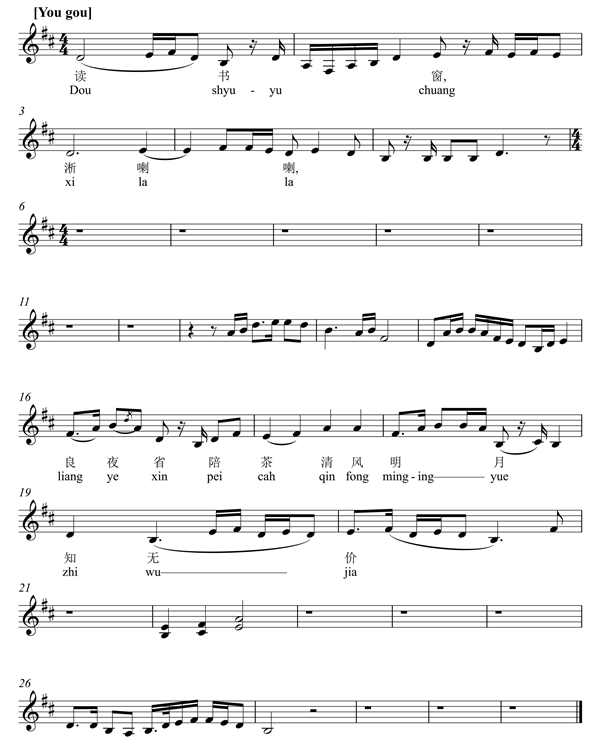

Music score of Shuangshengzi

In the original score, the rhythm featured 4th note rhythm and 8th note rhythm. And one word conformed to one note or two notes. The adapted version used 16th note rhythm.

Music score of Bei wei

Bei wei is the last qupai in the last scene of both the original play and the youth version. The aria was changed while the lyric remained intact. Dramatic changes occurred in pitch, melody, and rhythm.

Though aria allowed no change in traditional Kunju, Kunju music must adapt to the changing socioeconomic and cultural landscape. The youth version retained classic aria while recreating some qupai for dramatic effect unified by chorus.

In addition to changes in qupai(tune matrices)and aria, the youth version also applied polyphony music. Kunju music rarely or never used polyphony music. But the youth version applied music of this type to highlight dramatic effect. For example, in the scene 28 Union in the Shades, aria for the qupai-jinmayue was made by polyphony music and theme motifs, plus multiple musical instruments, to generate several melodies.

Theme music would leave a deeper impression on the audience. As some audience were not so familiar with qupai music, they found it hard to resonate with the melody, if every qupai appeared only once or twice. Theme music unified three parts with one particular melody.

The youth version of the Peony Pavilion was widely acclaimed in mainland China and beyond. It is a successful attempt to attract the younger generation to Kunju stage. Its success is largely attributed to music design. The music structure was adapted to contemporary aesthetics while retaining classic essentials. The music composition for opera was incorporated into the youth version. This play features theme music.

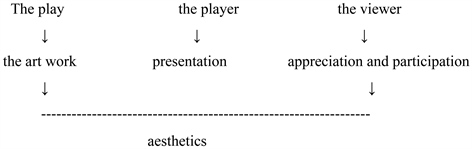

According to Gamader (2004), the play or artwork involves the play itself, player and viewer. The three parties interact with each other, but the viewer is the most important part from an aesthetic perspective.

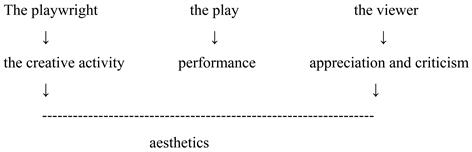

He rightly noted the significance of viewer or spectator in identifying the truth of the play or drama. But the equally important role of the playwright or those who adapted the play is overlooked. As the playwright creates play for the viewer to appreciate and critique, he/she should bear viewers in mind in his/her creation. The stage performance of the play is delivered by performers who shape its presentation. For every play, playwright, performer, and viewer interact with each other. Their relationship is characterized as the following diagram suggests.

5. Conclusion

The youth version of the Peony Pavilion gave a good example of how composers and directors sought to cater to the aesthetics of the younger generation in terms of music practice. Those creators incorporated musical elements that young people are familiar with under the framework of qupai (tune matrices). Repetition of theme music helped the young audience understand and capture the essential melody of the play.

NOTES

1Qupai is a term particular to traditional Chinese theater. Since no standard English translation exists, it is rendered in English as preexisting tune structures (Jones, 2014), tune matrices (Li, 2013), and aria matrices (Schoenberger, 2013). This paper uses tune matrices translated by Lindy Li Mark.