1. Background of This Report

This report grew out of a shopping trip taken with an immigrant woman to Diepsloot, a township near the Johannesburg of South African (Image 1(A) and Image 1(B)).

(A)

(A)  (B)

(B)

Image 1. Second-hand goods in Diepsloot, Johannesburg.

Many African women from Zimbabwe or Malawi were selling second-hand goods there. They disclosed that they had lived in South Africa for a long time, anywhere between five to ten years, and that relatives or neighbours from their original village worked there also. Similarly, the guide on this trip had also immigrated to South Africa for work. Not only her, but her brother and other relatives had been working in South Africa for many years. Looking around and listening to the stories of the sellers at the Diepsloot market, made it clear that her situation was common: many Africans immigrate to South Africa for work. This observation revealed a need to explore the reasons for their decisions to immigrate and then to remain.

What are the factors that push them to work in South Africa? What is life like as a result of this choice? These questions are the objectives of this report, which will be explored in the following sections.

2. Motivation of Immigrant Employment in South Africa

There are macro-economic reasons for the immigration of African workers to South Africa. In particular, the South African GDP per capita ranks quite high among African countries (Figure 1).

Micro-economic data in particular, the South African salary/income statistics—also help to explain the high number of immigrant workers. The numbers show that the average income in South Africa is much higher than the average incomes of many other African countries.

Consequently, after the African Union (AU) was launched on July 9th 2002, in Durban, South Africa, many foreign workers rushed to South Africa to find work or a higher paying job. Many foreign AU workers reported satisfaction with the higher salaries that they received in South Africa in comparison with their “home” country’s situation. For example, the guide on the excursion to Diepsloot explained her working experience in her home town as fraught with difficulties. She had previously worked for a small commissary for only 600 ZAR

a month. With such low wages, she had little enough money at the end of each month to support her family. They struggled financially. However, after coming to South Africa, and finding a position as a domestic worker, her higher pay allowed her to send some more money back to her family each month.

South Africa’s history and position as a regional economic powerhouse has made it a major destination country for immigrants from other African counties. As we show below (Figure 2), the average monthly earnings keep increasing. This is an important factor in attracting African immigrants.

Many of South Africa’s Expatriate African workers struggled to find work in their home countries due to economic instability. But they find employment in South Africa as low-skilled laborer e.g., as gardeners or domestic workers.

However, many native-born South Africans have complained about AU immigrants, claiming that they have stolen their jobs and lowered the country’s overall employment rate. However, in order to responded to the greater competition for jobs, research has actually shown that this situation has actually caused both native-born and immigrant workers to become more diligent employees, a result similar to the catfish effect.

Although money and jobs are among the most important factors governing African immigration to South Africa, a third reason is marriage. Nearly all of the female informants for this study expressed that they were unwilling to return to their home countries, especially after having lived in South Africa for many years. Many have married a native-born South African, and they now look to invite their relatives to South Africa to enjoy a better lifestyle. The immigration trends for immigrants in South Africa show that they all wish to achieve long-term stability in South Africa through either securing jobs or through marriage.

In some ways, the status of immigrants in South Africa is similar to that of other migrant nations like the United States of America (USA). Almost all South Africans are only one or two generations removed from immigrant origins. As Americans celebrate their heritage and identity as a “nation of immigrants,” many hold a deep ambivalence about future immigration. On the one hand, the “host country” benefits from the immigrant economy, but, at the same time, local

workers fear that subsequent immigrants will deprive them of employment opportunities and living space. Not all current residents of a country welcome new immigrants or even those who have recently obtained their Permanent Residency or official identity documents. This ambivalence to immigration is, given South African realities, ironic.

3. Overall Analysis of Immigrant Employment in South Africa

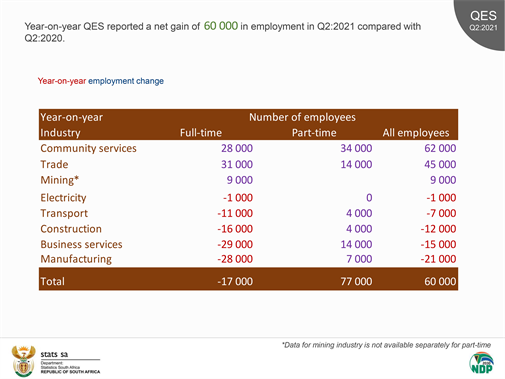

Any understanding of immigrant employment requires a preliminary review of the overall status of employment in South Africa. Based on government data from Statistics South Africa (Image 2), the employment numbers in various industries have increased, especially for part-time work. Their numbers show strong growth in 2021 as compared with data from 2020.

However, even though the salary and employment rate in South Africa is attractive for African immigrants, it is not especially strong when compared to many non-African countries.

● Comparatively low per capita income: In South Africa, the average household net-adjusted disposable income per capita is lower than the OECD average of USD 33,604 a year (OECD, 2021).

● Comparatively low employment rates: Nearly 44% of people aged 15 to 64 in South Africa have a paid job, which is below the OECD employment average of 68%.

● Gender disparity in employment: in South Africa 49% of men are in paid work, but only 38% of women.

● Long working hours: in South Africa, 18% of employees work very long hours, more than the OECD average of 11%. This is truer for men than women, as 22% of men work very long hours compared with about 13% of women.

Image 2. Year-on-year quarterly employment statistics report (Stats South Africa, 2021a).

The employment statistics shed more light on gender disparities in the immigrant work force. Although cross-border economic migration in this region has been dominated by male migrant labor to the South African mining industry, women have also immigrated across the regional borders to find work (Figure 3). Evidence shows that female immigration, especially to South Africa, has increased significantly over the past 10 - 15 years.

Overall South Africa’s labour market and data from Stats South Africa does not present good news for the feminist movement. According to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey of 2021, the South African labour market is more favourable to men than it is to women. Men are more likely to be in paid employment than women regardless of race, while women are more likely than men to be doing unpaid work. The rate of unemployment among women was 36.8% in the 2nd quarter of 2021 compared to 32.4% amongst men (according to the official definition of unemployment). The unemployment rate among black African women was 41.0% (Figure 4(A)) during this period compared to 8.2% among

white women, 22.4% among Indian/Asian women and 29.9% among coloured women.

In Dec 2020, according to data from the World Bank (Figure 4(B)), women in South Africa made up 45.47% of the labor force, a substantial increase over previous years. Therefore, female foreign workers may find the job market today to be more favorable than it had been even a year before.

Another key element to immigration for workers in Africa, is the ability to send remittances. Defined here as money transfers made by migrants to their relatives or others in their home countries. Representing the second-largest source of external funding for developing countries (especially African counties), remittances are recognized by governments and international organizations as important tools for reducing household poverty and enhancing local development.

According to statistics of global remittance recipient rankings (Figure 5), Nigeria receives the most remittance money of any nation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Many of these Nigerian workers have found employment in South Africa, some have gone further and also found space to create their own enterprises there.

Based on discussion with African immigrants, mostly female, in South Africa it appears that most maintain strong ties to family members in their home countries. Data from the Southern African Migration Project supports this. These ties lead to significant flows of remittances, of both cash and goods, sent to family members at “home”. The trend is that when African men and women come to South Africa for work, their families receive substantial economic contributions from them as a result (Figure 6).

After immigrants have sent the cash remittances, their families then usually spend the received cash in their home towns. Research shows the most common uses of cash remittances over the previous year were as follows (Table 1). It is evident that remittances are of considerable importance to families in the home country.

4. Conflicts and Benefits

Some conflict between local workers and foreign workers seems to be. In recent years, news stories have shown that refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa have lived in fear of being attacked due to xenophobia. When discussing the issue with foreign workers in Johannesburg, all asked were worried about it, especially because of how COVID-19 has impacted the African economy. They said that there have been reports of xenophobic attacks happening in their living areas. Some expressed the view that the only solution is to return to their home countries.

According to Deutsche Welle:

“South Africa often makes the headlines for violent attacks against immigrants. Xenophobia has now reached a new level with the creation of a group calling itself ‘Put South Africa First’.” (Thuso, 2020) (Image 3).

Violent attacks peaked in 2008 and again in 2015 (Figure 7). In 2015, there were outbreaks of violence against non-South Africans, mostly in the cities of Durban and Johannesburg, which resulted in the deployment of the army. About

![]() (A)

(A) ![]() (B)

(B)

Image 3. Hate and violence against foreigners in South Africa.

70% of foreigners in South Africa come from neighboring Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Lesotho. The remaining 30% is made up of people from Malawi, UK, Namibia, eSwatini, previously known as Swaziland, India among others. There are an estimated 3.6 million migrants in the country, a spokesperson for South Africa’s national statistics body told the BBC News, out of an overall population of well over 50 million.

According to a BBC article, published September 17th, 2019, foreign-owned business attacks resulted in the death of twelve people. This came at the same time as the South African Government was attempting to strengthen ties with Nigeria, another of Africa’s strongest economies (BBC, 2019).

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa said about this incident that, “We are very concerned and of course as a nation we [are] ashamed because this goes against the ethos of what South Africa stands for.”

In order to control and manage this type of conflict, earlier in 2019, South Africa launched its National Action Plan to combat xenophobia, racism, and discrimination, marking an important step towards addressing the widespread human rights abuses arising from xenophobic and gender-based discrimination and violence.

Regardless of sentiments against migrant workers, in reality they contribute to the South African economy. Many immigrants run businesses that often provide jobs to native-born South Africans. Data from the International Labor Organization documents their economic benefit to the country:

“Based on the sectoral distribution and education of workers in 2010, the contribution of immigrants to GDP that year is about 9%, and immigrant workers can bump the South African income per capita up by up to 5%.

Immigrants also have a positive net impact on the government’s fiscal balance. This is because they tend to pay more taxes (Figure 8). In 2011, the per-capita net fiscal contribution of immigrants ranged between 17% and 27%. Native-born individuals, on the other hand, contributed −8%” (OECD/ILO, 2018).

Visits to townships like Diepsloot supports the claim that immigrants benefit the economy. For example, most second-hand clothes retailers are self-employed, and therefore not displacing any native-current workers from their jobs as people claim. In fact, immigrants integrate into and increase the local economy.

5. Conclusion

How can South Africa strike a balance between migrant-workers needs and local residents’ needs and feelings?

In terms of addressing the need to emigrate at all, ideally if poorer Africa countries were able to strengthen their economies, and create jobs, their citizens would not feel the need to look elsewhere for better opportunities. However, it is a challenge to improve these economies quickly: Rome was not built in a day.

As shown by the research from the IMF and the World Bank, nearly all of African countries depend upon some form of external support. This support also makes-up one-quarter of the IMF’s total “technical assistance.”

“IMF currently is supporting programs in 23 African countries through their concessional Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF)” (IMF Staff, 2003).

The World Bank is also involved in funding economic recovery and support to much of Africa in the face of the Covid-19 Pandemic. With so much debt hurting these economies because of this difficult period the AU Commission Moussa Faki Chairman has more recently said: “We will never tire of calling for urgent debt restructuring accompanied by a bold policy that goes beyond special entitlements to alleviate the pressing need for immediate cash for vaccine purchases and to lay the foundations for economic recovery” (African News, 2021).

However, through these plans there is a hope that the economies of those African countries that workers are emigrating from can hope to find good work at home.

South Africa, as one of Africa’s top-ranking countries, has attempted to implement key recommendations to stimulate its economy and create more domestic opportunities (Figure 9). Duplicating the economic success of African countries like Ethiopia may be one method.

Ethiopia’s rise has been largely driven by an increase in industrial activity, including investments in infrastructure and manufacturing. According to the IMF data, “foreign direct investment growth was 27.6% in 2016/2017, with investments going into new industrial parks and privatization inflows” (IMF, 2018).

Ethiopia has been selling its state-owned businesses to outside investors like China. China has become not only Ethiopia’s biggest foreign investor but also its largest trading partner. Ethiopia has also encouraged foreign investment in its manufacturing industry, hoping to compete with India and China with its cheap labor costs. Fashion brands like H&M, Guess, J Crew, and Naturalizer have already established manufacturing centers there. When African counties can provide more jobs for their residents, the immigrant trend shall become weaker.

Boosting the economy and generating more employment opportunities for all who are currently residing in South Africa could also potentially aid in preventing xenophobic attacks against migrant workers. A reduction of domestic unemployment leads to a local work force that does not feel “threatened” by migrant workers.