Parental Involvement in the Education of Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in Kenya ()

1. Introduction

A growing body of research suggests that when parents of learners with disabilities collaborate with the school effectively, students learning outcomes improve (Meadan et al., 2009 [1]; Dunlap, Ester, Langhans, & Fox, 2006 [2]; Meadan, 2014 [3] ). Additionally, studies reveal that parents’ involvement in the education of children with disabilities, apart from helping improve their performance, also provides a strong learning motivation that is a prerequisite for these learners. Parental involvement also helps to nurture and cultivate a good relationship between parents and teachers and build up a more positive and suitable school environment favourable for children (Hsieh, Rimmer, & Heller, 2012) [4]. It is worth noting that parents are the first and most important teachers that children encounter.

Despite the positive role effective parental involvement plays in the education of learners with disabilities, studies from Kenya show that the involvement is quite minimal, if any at all. Okoth (2014) [5] and Weke (2012) [6] indicate that parental involvement in the education of learners with disabilities in Kenya is rare and consequently, parents do not effectively meet the educational needs of their children. Accordingly, parents do not understand their roles in the education of learners with disabilities. Hagreaves (2011) [7], observes that in most countries, parents have lost the original teaching function and learners with disabilities are the most affected by this negligence. Consequently, parents have become observers in the teaching process of children with disabilities.

Thus, this necessitated the need to establish the extent to which parents got involved in the education of learners with intellectual disabilities in Kenya followed by a determination of the areas of parental shortcomings and neglect in the education of learners with intellectual disabilities in Kenya.

The low intelligence quotient (below 70 - 75), that is characteristic of learners with Intellectual Disabilities (ID), implies that the learners are not as fast as typically growing children at acquiring academic and social skills. Thus, learners with intellectual disabilities present with high support needs in adaptive behaviour and intellectual functioning. Notably, their disability affects the cognitive and intellectual capacities that are vital for knowledge acquisition. However, increased parental involvement has been proven to be one of the ways through which enhanced learning outcomes can be achieved for these learners. Additionally, studies have revealed that parental involvement, support, encouragement, and positive reinforcement are linked to children’s learning competence, a strong feeling of self-worth, healthy social relations, and fewer behavioural problems (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005 [8]; Kurani, Nerurkar, Miranda, Jawadwala, & Prabhulkar, 2009 [9] ). Thus, this paper sought to establish the roles that parents of learners with intellectual disabilities in Kenya play in their children’s education, the extent of the involvement and a determination of the areas of parental shortcomings and neglect with a view to finding ways of surmounting them.

2. Literature Review

Roberts and Kaiser (2011) [10] classify the benefits of parental involvement into four categories: to meet parental informational and emotional needs concerning their children’s education, use parents as change agents and benefit from parents as a source of information regarding the student. Accordingly, parents who make time to read to their children, avail books and other learning resources, take academic trips, guide television watching, monitor behaviour end up providing stimulating experiences that contribute to student achievement.

Hsieh, Rimmer, & Heller (2012) [4] also indicate that positive and timely parental involvement can help stimulate children’s intellectual, social, and even physical development. Additionally, good parent behaviour can set the stage for children to develop and use coping skills that make them more resilient to problems.

Furthermore, Parental involvement could also reinforce and complement teachers’ efforts as teaching learners with intellectual disabilities requires repetitive and remedial teaching (Hsieh et al., 2012) [4]. Effective parental involvement would also ensure that parents help with continuity and practise of skills learnt at school (Emerson, Fear, Fox, & Sanders, 2012) [11]. Furthermore, when parents are adequately involved in their children’s education, they act as a source of information regarding students’ progress and challenges that students’ encounter at home (Hsieh et al., 2012) [4], hence the need for parents to adequately get involved in the education of their children with ID.

Prevalence and Types of Intellectual Disabilities

Intellectual disability affects about 1% of the population and it is a condition characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour as expressed in conceptual, social and practical adaptive skills, accordingly, this disability manifests itself before age 18 as it is a developmental disability (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2010) [12]. Therefore, children with ID require special attention from all they interact with including, parents, siblings and the community.

Causes of ID vary and can be categorised as prenatal, perinatal, or postnatal (Ke & Liu, 2012) [13]. Prenatal causes exert their effect before birth and include genetic, maternal diseases and infections, maternal exposure to toxins (alcohol, drugs, and tobacco) during pregnancy and neural tube defects. Genetics are responsible for conditions such as fragile-x syndrome, down syndrome, and phenyl-ketonuria (PKU). While diseases and infections such as HIV/AIDs can devastate and cause trauma to an unborn baby leading to intellectual disabilities, neural tube disorders such as anencephaly and spina bifida (incomplete closure of the spinal column), are also prenatal causes of intellectual disabilities (Haworth, Tumbahangphe, Costello, et al., 2017 [14]; Ke & Liu, 2012 [13] ).

Perinatal causes exhibit their effects during the birthing process and include birth injuries due to oxygen deprivation (anoxia or asphyxia), umbilical cord accidents, obstetrical trauma, and head trauma. They also include low birth weight. On the other hand, postnatal causes present their effect after birth and include child abuse/neglect, environmental toxins, accidents, and diseases such as meningitis, whooping cough, and measles (Smith, 2010) [15]. However, in two-thirds of all children with ID, the cause is unknown.

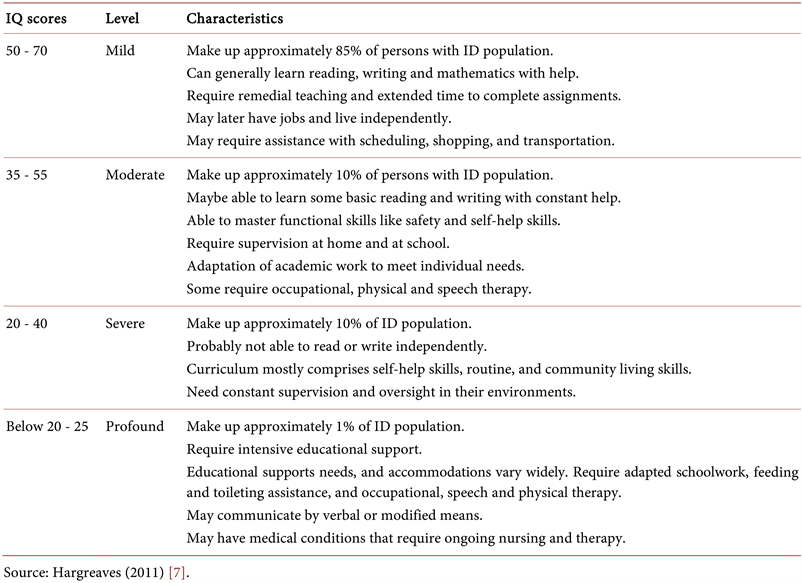

Consequently, learners with intellectual disabilities show limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour. Intelligence functioning is ordinarily determined by use of an IQ (intelligence quotient) test. The average intelligence quotient is 100, with the most people scoring between 85 and 115. According to the AAIDD (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2010) [16] a person is considered intellectually disabled or impaired if he or she has an IQ of less than 70 to 75 The severity of the intellectual disabilities varies from mild to profound as shown in Table 1 below.

This study considered all the categories of learners with ID who are educable,

Table 1. Description of severity of intellectual disabilities.

that is, those that have moderate to mild ID. Table 1 shows that approximately 95% of all persons with ID are educable.

The fact that most persons with ID have a mild disability implies that these learners are just little slower than average to learn new information and skills. It is noteworthy that, with the right educational support, most can live independently as adults. However, learners with profound disabilities usually present other medical conditions that may require continuous nursing and medical attention thus making them unable to attend school regularly. The medical conditions impact negatively and interfere with the child’s ability to learn and benefit from schooling (Groce, Kett, Lang, & Trani, 2011) [17].

A learner with ID typically presents with support needs in adaptive behaviour and functional life activities including: difficulty with problem-solving, logical thinking, difficulty remembering things, inability to connect actions with consequences, behavior problems such as explosive tantrums, slow to master things like dressing and feeding, have trouble with speech or delayed speech development among other things. In severe or profound intellectual disabilities, other health problems may be present which include: anxiety, motor skills impairment, seizures, mood disorders, lack of coherence and organization in writing and speaking, hearing problems and vision problems (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2010) [12].

Consequently, learners with ID find it difficult to perform various social and adaptive skills such as communicating and socialising with others and in most situations, looking after themselves. All these problems pose a challenge to the learners’ acquisition of knowledge and skills thereby necessitating enhanced parental involvement in their education if at all they have to reach their maximum potential in education. Notably, their disability affects the cognitive and intellectual capacities that are vital for knowledge acquisition. Increased parental involvement has however proven to be one of the ways through which enhanced learning outcomes can be achieved for learners with ID (Luckasson, 2013) [18].

Despite the numerous benefits of parental involvement in education, a study by Okoth (2014) [5] reveals that parents have lost the original teaching function and learners with disabilities are the most affected by this negligence. Accordingly, parents have become distant observers in the teaching process of children with disabilities.

Of serious concern, however, is the fact that Kenyan scholars (Okoth, 2014 [5]; Weke, 2012 [6] ), note that, parental involvement barely exists in Kenya. Accordingly, parents have absconded and neglected their upbringing roles and left the whole burden to the teachers. Subsequently, parents of Learners with Disabilities (LWDs) do not adequately understand their role in the education of LWDs. This study, thus, collected data from sampled parents with an aim of determining the extent to which they got involved in the education of their children with Intellectual Disabilities in Kenya and their areas of shortcoming with the long term aim of determining strategies of intervening on the problem.

3. Methodology

The country, Kenya, was divided into 8 regions, in an attempt to arrive at some geographical proportionality in selecting the sample even though sample proportionality was not a requirement since this was a qualitative study. However, it was vital for parents’ voices from all regions of Kenya to be heard and documented. The 8 regions/clusters were in line with the previous (now defunct) provincial administrative units namely Western, Eastern, North Eastern, Rift Valley, Central, Coast, Nyanza, and Nairobi. Kenya occupies a total surface area of 582,650 km2.

Purposive sampling was utilised to select the participants. The purposes that were followed included parents’ knowledge of the issues under investigation and the aspect of a parent having a child with ID at school at the time of data collection. Parents who had had children with ID at school for a longer time were prioritised as they were presumed to have more experiences pertaining to educating a child with ID. The 24 parents (three from each provincial region) that were selected had in-depth experience of parenting and educating a child with ID and could provide information to fulfil the purpose of the study. In line with the qualitative methodology the study adopted a phenomenological approach. This enabled the capturing and documenting the voices of parents which were later transcribed. The methodology also enabled the decimation of face to face non-verbal cues that would otherwise be lost. Data were mainly collected through semi-structured interview guides, which lasted approximately 45 minutes each. The collected data were analysed with the help of Atlas.ti software package.

4. Results and Discussion

This qualitative study aimed at establishing the extent to which parents of learners with ID got involved in their children’s education followed by a determination of areas with shortcoming and neglect as far as parental involvement is concerned. The study established that the parents got involved in their children’s education, albeit to a given extent. The parents transported their children to school, monitored their behaviour, provided learning resources and subsistence, and enabled a safe home environment. On the other hand their areas of shortcomings and neglect included: lack of involvement in children’s school activities for instance not volunteering at school, not exposing their children to educative environments like museums and game parks to help stimulate their cognitive abilities and imagination, inadequate provision of learning resources and not engaging with the schools as discussed in subsequent sections.

4.1. Extent of Parental Involvement in the Education of Learners with ID

4.1.1. Transporting/Taking Children to School

The parents took their children to school when schools opened and picked them up when the schools closed. Evidently, this was a big task as in the excerpt below:

“…I always take my son to school when schools open. I would never want him to miss school even for a day. He is in a boarding school thirty kilometers away. I always take him on time.” (Parent 6: Interview on 7th March 2018)

The role of taking children to school was quite significant as teaching and learning can only take place with the presence of learners. Another parent expressed the same sentiments and said that he ensured his son got to school on time and even indicating that some parents of learners with ID still refuse to take their children to school as reported:

“…I always take my son to school. I want him to be taught so he can become better. I also get him back home when schools close. I know some parents who have refused to take their children with intellectual disabilities to school though.” (Parent 5: Interview on 30th March 2018)

The task of taking children with ID to school was considered quite significant largely because of the stigma associated with having a child with ID in Kenya. Weke (2012) [6], reports that for a long time, in most African communities, ID was regarded as a social failure. This led to parents of children with ID hiding them from the public. Taking them to school took a lot of courage and commitment from the parents. Hargreaves (2011) [7] indicates that making the decision to take a child with disabilities to school marks a turning point in the life of the child and his/her family. Accordingly, it is a big step forward for all stakeholders. Thus, this component of parental involvement was phenomenal.

4.1.2. Provision of Learning Resources

From the findings, even though most of the parents struggled economically and were not always in a position to provide all the learning requirements outlined by the schools, they tried as much as they could to provide as reported:

“…I try to provide toiletries, pencils, exercise books and some pocket money for my child whenever I can. The money is usually kept by the class teacher and it is used when need arises.” (Parent 11: Interview on 21st March 2018)

It appeared that the learning requirements were many, usually beyond the parent’s ability to provide them all as some of them faced acute financial constraints as reported thus:

“…I always try to buy school requirements even though they are usually too many compared to my meagre financial earnings, I have never managed to provide everything though.” (Parent 12: Interview on 31st March, 2018)

The above vignette implies that it was sometimes strenuous and difficult to buy or provide all the requirements as stipulated by the schools due to extreme poverty and other financial constraints, however they tried their best given the circumstances. Gutman and McLoyd (2006) [19] reiterate the need for parents to play bigger roles in their children’s education by providing learning resources and contributing funds towards school projects that benefit learners. Accordingly, learning materials are essential and make learning more realistic more so for learners with ID. The importance of learning materials in teaching learners with intellectual disabilities cannot be overemphasized. Learning and play materials are a prerequisite for teaching learners with ID as they learn best when abstraction is removed and replaced by concrete tangible learning materials.

Similarly, studies (Epstein (2005) [20]: Oranga, Chege, & Kabutha, 2013 [21] ), state that teaching and learning require certain equipment and material that make it more realistic, simple and meaningful to the learners, especially those with learning and intellectual disabilities. Epstein (2005) [20] also reveals that, learners with learning and intellectual disabilities require a lot of visual and tangible learning as opposed to abstraction as this makes the learners to register and understand the concepts being learned easily. Accordingly, this enriches learning and provides vivid education experiences for children with IDs. Hence, the parents are required to avail the learning materials for the children to experience enhanced educational outcomes since provision of adequate learning materials would lead to improved grasping of concepts taught.

4.1.3. Behaviour Monitoring and Modelling

Learners who present with problem behaviour barely benefit from learning, regardless of whether they have disabilities or not (Hsieh et al, 2012) [4]. However, the situation worsens where learners with intellectual disabilities are concerned. Behaviour monitoring and modelling by parents of learners with intellectual disabilities was quite imperative as learners with intellectual disabilities more often than not present with problem behaviour, consequently making this theme extremely important. The parents mentioned the fact that they watched their children all the time and stated that sometimes their children would engage in bad behaviour, for instance, spitting food, breaking household items or crying uncontrollably for no known reason. The parents, consequently tried their best to correct these behaviours whenever they noticed them, as reported:

“…I keep an eye on my son all the time; I try to teach him what is right and discourage bad behaviour. He used to scream whenever he wanted food, I discouraged it and he does not do it anymore, he used to get out of control.” (Parent 11: Interview 21st March 2018)

Subsequently, another parent indicated her daughter would fall and become hysterical and wriggle on the floor at the slightest provocation, but she managed it and it stopped, as indicated in the following excerpt:

“…if I do not teach my daughter wrong from right, she will never differentiate the two, I always ensure she does not engage in bad behaviour. She used to become hysterical and wriggle on the floor, she does not do it anymore as I discouraged it.” (Parent 2: Interview on 11th March 2018)

Thus, it appears the parents watched, monitored, and modelled their children’s behaviour. Apparently, they reinforced good behaviour and rebuked bad behaviour. Other parents used reward to reinforce good behaviour and rebuke bad behaviour as reported below:

“…whenever my son does something good, I reward him, for instance I buy him his favourite snack but I frown and rebuke bad behaviour, he realises his mistake and does not repeat it.” (Parent 1: Interview on 31st February 2018)

This was quite important because if problem behaviour is noticed early enough and intervention measures put in place in good time, rectification is easier. Proper behaviour would lead to better academic outcomes. El Nokali, Bachman and Votruba-Drzal, (2010) [22], suggest that children with problem behaviour such as bipolar disorders, tantrums, etcetera, do not register good educational outcomes as their peers without problem behaviour. Yet learners with ID sometimes present with such behaviour. El Nokali et al (2010) [22] advice parents to apply behaviour management strategies and strive to nurture strong family relationships with the children. Accordingly, the behaviour management role of a parent is indispensable Furthermore, Duch, 2005 [23]; Sheldon and Epstein, (2005) [24] in a longitudinal examination of parental involvement across a nationally representative sample of first, third, and fifth graders in the Unites States established that enhanced parental involvement predicted declines in problem behaviour amongst adolescents, leading to improved educational outcomes. Moreover, studies (Grech, 2009 [25]. Hsieh, 2012 [4] ) show that enhanced parental intervention and involvement can also set the stage for learners with ID to develop and use coping skills that make them more resilient to problems. This, thus, necessitates the need for parents to play a bigger role in management of their children’s behaviour that would consequently lead to enhanced educational outcomes.

4.1.4. Provision of a Safe Home-Environment for Learners with ID

The parents indicated that they tried their level best to ensure that their children stayed in a safe environment while they were at home as the children’s disability put them at risk of self-harm or inflicting harm on others without intent as reported below:

“…I make sure the home is safe for my child. I remove all objects that may harm him like knives, razor blades and ensure he does not play with electric sockets or plugs as he is a little slow in realising the danger that such items pose when not used well.” (Parent 15: Interview: 22nd April 2018)

This was a significant contribution by the parents as these learners needed a safe and hazard-free environment to live in. Injuries and pain associated experiences would interfere with their school attendance and learning and threaten their general health and wellbeing. This would further complicate their situation as they are already disadvantaged by their disability. It was therefore imperative for parents to ensure a safe and hazard-free home environment.

In the same vein, another parent reiterated the sentiments stressing the fact that she made sure there was a caregiver at home to keep an eye on the child every time she left home as reported:

“…before I leave home, I always make sure there is someone around to keep an eye on my son, this ensures that he does not do anything harmful to himself or others. We also keep away things that can harm him to protect him.” (Parent 12: Interview on 20th, April 2018)

Similarly, a parent who once left her daughter unattended and found her injured had similar views and indicted that she never leaves her daughter unattended as reported in the following excerpt:

“…I left my daughter alone once for a short while and found her writhing in pain, she had stepped on hot charcoal near the fireplace. Since then I never leave her alone because she still cannot tell wrong from right.” (Parent 20: Interview on 21st, April 2018)

The above findings are in line with the sentiments expressed by Epstein (2010) [26] who reiterates that effective parental involvement should involve provision of a safe, healthy and sound nurturing environment for all children regardless of whether they have disabilities or not as this is the main function of parenting. Accordingly, a healthy safe and hazard free home environment would also give parents a peace of mind and enable them to focus on other activities that are beneficial to the entire family. Thus, ensuring a hazard-free environment is a vital component of parenting that should never be overlooked, more so where children with intellectual disabilities are concerned.

4.2. Parental Shortcomings/Neglect

From the above discussions, the parents played some roles in their children’s education. However, the roles were not adequate and were largely non-academic. The findings revealed that, the parents did not help their children academically or express interest in whatever they were learning at school yet academic involvement is vital as the vast majority of learners with ID require task analysis, repetitive and remedial coaching in order to grasp concepts. Consequently, parents are expected to complement teachers’ efforts by helping these learners with academic, social, and daily living skills taught at school.

Blacher & Hatton (2007) [27], indicate that parental involvement in the education of learners with ID should be more intense and should include additional coaching/teaching at home and provide opportunities for continuity and practise skills taught/learnt at school. Accordingly, parents should help learners with intellectual disabilities to practise academic, daily living and adaptive skills (for instance teeth brushing, toilet training, hand washing and shopping) taught at school.

4.2.1. Not Initiating Home Based Learning or Acting as Home Teachers

Learners with ID need repetitive and remedial teaching/learning; consequently, parents are expected to play a significant role in their education by helping with homework and acting as home teachers. However, findings revealed that this did not happen. The parents did not help their children with schoolwork, neither did they act as home teachers as expected, as revealed, thus:

“…I do not know how to help my daughter with schoolwork, as I do not know what they are taught at school. The teachers never tell us how to help them.” (Parent 18: Interview on 30th April 2018)

Apparently, the parents did not know what the children learnt at school, although they could have inquired from the schools how to help the children at home. Similarly, another parent indicated that her son never told her anything about schoolwork, so she never bothered to find out as reported in the following excerpt:

“…my son does not tell me anything about his schoolwork or classwork, so I do not know if he has a problem. I think he is doing well. Teachers help them at school.” (Parent 3: Interview on 6th April 2018)

It appeared that lack of school talk or helping children with home/schoolwork by the parents might have been due to low parental education. Some parents wished they could help their children, but reckoned that they did not know what the children learned at school as reported thus:

“…I would teach her (daughter) at home if I knew how and what to teach, but I think I cannot understand some of the things as I did not go to school well.” (Parent 11: Interview on 20th, April 2018)

Apparently, the parents wished they could be knowledgeable enough to support their children with academic activities but seemingly, low parental education and lack of communication from the teachers made the situation worse. Machalicek, Lang and Raulston (2015) [28] indicate that with structured coaching and training, parents should be able to do more for their children. However, this would only be possible if the teachers and parents cooperated and worked together for the benefit of the learners. Instead, the parents expected their children to be the ones to raise school issues with them, yet these children had a disability that rendered them unable to come up with such discussions as frequently as they should without being prompted. Mills (2015) [29] contends that, parents should engage in home-based learning activities that include helping with children’s academic work, supporting children through encouragement, play and concerts in order to enhance their educational experiences. Furthermore, studies (Senechal 2006 [30]; Oranga, Obuba & Boinett 2022 [21] ) reiterate that parental involvement in the education of learners with ID should be more intense and include additional coaching/teaching at home and provide opportunities for practise and continuity of skills by helping the learners to practise the daily living and adaptive skills learnt at school. This was apparently lacking in the situation of parental involvement in the education of learners with ID in Kenya.

4.2.2. Lack of Membership/Enrolment in School Committees, Boards and Parent Teacher Organisations (PTO)

Additionally, the parents seemed not to know that there were other varied ways of participating in their children’s education that could boost the children’s educational outcomes in the long run. Case in point, they did not know or mention belonging to school governing bodies like Parents Teachers Associations (PTAs), or school governing councils or Boards of Management (BOM) as would be expected of them. When appointed, the vast majority declined the offer. The parents who lived far from school indicated that distance was the barrier to their membership and contribution as reported, thus:

“…I live far from the school and as such I cannot belong to school governing bodies. I think members of these boards need to live close to the school as they can be called upon any time.” (Parent 10: Interview on 25th April 2018)

Other parents reported that they could not belong to school management boards because they did not have time to contribute to the discussions and deliberations as reported, thus:

“…it is hard for me to be a member of these organisations as I am busy. I must fend for my family too, I have a big family to feed.” (Parent 15 Interview on 26th, February 2018)

Similarly, other parents indicated that they could not belong to the committees because they could not understand the deliberations in the committees and as such did not see the need as indicated thus:

“…the Board of Governors and Parents Teachers Association require people who are well learned so I think I might not fit in as I did not go to school really well.” (Parent 1 Interview on 27th, February 2018)

From the findings, it was obvious that most of the parents did not play any role in parents’ committees and had no membership to school governing bodies. They apparently did not know the usefulness of these school bodies. These committees are also the main decision making organs of the schools, thus most of the parents missed out on making decisions that impact their children’s education.

Coupled with this was the failure to attend school meetings despite invitations from the schools yet is quite imperative for parents to attend meetings, organise and contribute to fund raising functions and provide games and learning materials for their children in an effort to ensure enhanced school/home collaboration.

4.2.3. Inadequate Provision of Subsistence and Learning Resources

The parents’ acknowledged the fact that they did not provide enough for their children in terms of learning resources and subsistence due to economic constraints and wished they could do more as reported:

“…I wish I could provide all the school requirements for my daughter. However, I am not able to because I have two other children at school whom I try to provide for as well. They do not have disabilities though.” (Parent 9: Interview on 22nd, April 2018)

The above sentiments imply the parents knew that they were not doing enough in the education of their children with IDs as concerns provision of learning resources and subsistence. From the excerpts, the circumstances they lived in did not allow them to provide enough for their children with ID since they had other children to provide for Ruskus and Gerulaitis (2010) [31] indicate that the number of parents in the general population that are experiencing difficulty with regard to managing and responding to their children’ educational needs is on the rise, yet the development of good parenting skills, including provision of learning resources has been considered a basic mechanism in initiating and improving cognitive and academic processes in learners with IDs.

4.2.4. Not Engaging in Constructive Play with the Children

Children with ID learn best in relaxed environments, for instance during play. Play-based learning occurs when play activities are used to teach cognitive skills. The parents seemed not to be aware that they could play with their children and incidentally teach them cognitive skills. The hurdle was that they were also too busy to do so as reported:

“…my daughter plays with other children, I have never played with her because she has many play mates and I also run several errands for the family throughout the day.” (Parent 9: Interview on 22nd, April 2018)

Similarly, other parents indicated that their children played with their peers and further reported that all they did was to provide play materials, albeit to a given extent, as reported:

“…he plays a lot with other kids; he loves to play. I do not take part in his play though, I only try to provide him with balls and other materials that I can afford.” (Parent 3: Interview on 12th April 2018)

Other parents indicted that they did not know the importance of play or the fact that they were supposed to play with their children but indicated a willingness to play with them if it would help the children, as reported in the following excerpt:

“…I did not know that I am also supposed to play with him, I will be doing it. Maybe he can improve if I teach him a few things during play.” (Parent 8: Interview on 15th, April 2018)

From the findings it is evident that parents need to be educated on the role of play in a child’s development and even more so those with developmental disabilities like ID. Roberts and Kaiser (2011) [10], indicate that parents who make time to play and provide stimulating experiences for their children contribute to student achievement. On the other hand, Jenvey (2013) [32], indicates that children with ID have delays in intellectual functioning (learning, reasoning, and problem solving) and adaptive behaviours needed for everyday living, consequently such children develop play forms more slowly than typically developing children, and spend less time playing with others, because many of them have language delays and/or sensory impairments, hence the need for parents to initiate play with these children.

Furthermore, Mills (2015) [29] indicates that parents are the key caregivers, teachers and socializing agents for their children and as such their role in their children’s education cannot be overlooked as they know and understand the children better than the teachers. This insufficiency in parental involvement is in line with the sentiments echoed in Kenya by Okoth (2014) [5] who reiterated that parental involvement in the education of learners with disabilities is low. According to the authors, parents in Kenya do not effectively meet the educational needs of their children.

4.2.5. Failure to Expose Their Children to Supplementary Learning Environments

Gutman and McLoyd (2006) [19], reiterate the need for parents to complement teachers’ efforts by exposing the children to real and practical learning environments like visiting museums, game parks or agricultural production and manufacturing firms. Accordingly, this would enrich learning and provide vivid educational experiences for learners. On being asked whether they took their children on educational walks, tours or engaged in cognitive stimulating activities with their children, the parents indicated that the practical learning environments apart from being quite far, visiting them required a lot of money to facilitate transportation and entry, which they did not have, as reported, thus:

“…I have not taken my son anywhere to learn because the factories I know of are quite far, one is in Kisumu (a town in Western Kenya), and I do not have money for transport.” (Parent 4 Interview on 24th, February 2018)

Another parent (who worked for the government) expressed similar sentiments and said she had never taken her daughter to the game park but intended to do so in the near future as reported thus:

“…I have never taken my daughter to a different practical learning environment, but I will take her to the zoo, I guess she will like it.” (Parent 4: Interview on 27th, March 2018)

Hence, economic constraints played a major role in the parents’ inability to expose their children more. According to Senechal (2006) [30], parental involvement in the education of learners with ID should be more intense and include additional coaching/teaching at home. It should also provide opportunities for learning in the community. Accordingly, parental participation needs to reinforce and complement teachers’ efforts by parents finding time to expose their children to different learning environments that may help stimulate their cognitive abilities.

4.2.6. Not Engaging in Communication with the Schools Concerning Children’s Performance/Progress

The parents confessed that they did not engage in communication with the schools concerning their children’s performance. They thought it was not necessary as their children would not perform as well as their counterparts without disabilities as reported in the following excerpt, thus:

“…I do not talk with teachers because I do not think my son can perform better than he is doing already, he has a disability, but he is trying his best.” (Parent 19: Interview on 30th April 2018)

Apparently, the parents had despaired and believed nothing good could come out of their children. This might have been as a result of ignorance as most of the parents were not educated to higher levels and as such they might have assumed that it was needless to bother about the education of their child with ID as they would not achieve much in school. Senechal (2006) [30] reiterates that parents need to be enlightened on advanced levels of involvement. These may include parent-teacher communication, new technology, modelling children’s behaviour, identifying the right play materials for early learning for children with intellectual disabilities, provision of safe and stable environment at home and intellectual stimulation.

Additionally, the parents admitted that they did not volunteer in the classrooms as teacher assistants whenever possible as would have been the case, and even more so for parents living near the school. This might have been since the parents did not understand their role well necessitating the need for parental education. Furthermore, the parents did not talk about school or help their children with homework; they thought this was the responsibility of the teacher. The above situation may have resulted from numerous factors including lack of time, unwelcoming school environments, stigmatisation of persons and families of learners with intellectual disabilities and ignorance/low parental education.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

The study established that parents of learners with ID in Kenya got involved in their children’s education to a given extent. The roles that parents played included: taking their children to school (which required a lot of courage amidst societal stigmatisation of persons with ID), provision of learning resources and subsistence (amidst severe economic constraints that the parents faced), provision of a safe home environment, watching and modelling their children’s behaviour (as learners with ID sometimes present with problem behaviour). On the other hand, their areas of shortcoming included: failure to get involved in their children’s schooling activities, not exposing their children to educative environments like museums and game parks to help stimulate their cognitive abilities, failure to volunteer at school, inability to provide sufficient learning resources/subsistence, inability to attend school meetings and failure to enlist as members of school/parents’ committees. They also rarely enquired about their children’s school progress.

5.2. Recommendations

1) There is a need for the Ministry of Education to spearhead the enactment of policies, guidelines and laws that would legitimize and govern school/home collaboration as the findings revealed that these laws are lacking.

2) The Ministry of Education should educate parents of learners with ID on the need and benefits of parental involvement in education using brochures, seminars and community workshops.

3) There is a need for the government to initiate ways of emancipating the parents economically (through financial subsidies and income-generating projects), as they are already disadvantaged by the burden of taking care of a child with ID, some of whom present with multiple disabilities that require frequent medical attention.

4) The government, non-governmental organisations and faith-based organisations should work together to help to demystify ID consequently reducing stigmatisation of persons with IDs.

5) Incorporation of a component of “working with parents” in the teacher training curriculum in Kenya to equip teachers with skills needed to collaborate and engage with parents. This will also help bring about attitude modification towards parents and enable the teachers to create opportunities for parental involvement in school activities.

6) Introduction of official parent-engagement schedules by the Ministry of Education that would authenticate parental involvement in education.