Impact of the Gender of the Tunisian Teacher on the Representations of the Dynamics of Physical Education Sessions and Its Concretization ()

1. Introduction

For Sarthou (2003), teaching PE is certainly teaching physical and sports activities to induce, on the one hand, the educational and didactic reflections of the teacher and on the other hand, to contribute to psychomotor education, socialization and autonomy in students. According to Saury, Ria, Séve and Gal-PetitFaux (2006), to achieve targeted transformations in students, the PE teacher prepares environments that allow student learning. So whatever the reference learning theory used, the preparation of appropriate and effective spatiotemporal and material devices is at the heart of one’s professional activity. “In PE, the activity of the protagonists takes place in shared spaces, according to configurations regulated by times, spaces and interactions continuously negotiated between the actors… The teacher’s interventions are then organized around the exploitation of human resources (class group) and material (space, objects, music), with a double concern: to control order in the class and to maintain the commitment of students at work and instruct students according to the targeted learning” (Brun & Gal-Petitfaux, 2006). For these authors, it is on the temporal and spatial organization that the lessons are strongly based. The dynamics of the teacher-pupil and pupil-pupil social interactions are organized by the topography of the places. The architectural configuration, the spatial arrangement of the pupils and the objects present are such as to orient the form of the activities taking place in the classroom. Gymnastics has a relatively important place in the programming of physical and sports activities within the school environment alongside athletics since its events are part of the national baccalaureate examination. Except that gymnastics is a physical activity whose complexity is recognized both in practice and in teaching. Risk-taking and accidents make teachers and students dread this activity and cause fears when implementing a gymnastics cycle. For Bordes (2005), it is an individually practiced activity called “psychomotor” (Parlebas, 1981), deserving of a unique school treatment. In fact, the systematic grouping of students to work in workshops transforms it into a situation of “coaction” (Bordes, 2005: p. 14). For Durny (2008), the organization of a gymnastics session in PE is indicated by an aspect of complexity and dynamism. Indeed, the students are dispersed occupying different spaces by their workshop and doing different tasks such as performing figures, parrying or helping a classmate. In addition, the teacher is asked to move from workshop to workshop to correct, explain, adjust a device according to the needs of the students, place himself on the most risky workshop to ensure the safety of the students, however, without losing any view of the whole class. Following this multidisciplinary work on the analysis of teaching practice, Altet (2002) affirms that this analysis deserves to take into consideration, at the same time, the pedagogical and didactic management of the content as well as the interactivity in the context where the teaching practice occurs (in situation) and to understand the meanings which emerge in situ and which are taken into account by the authors. The author adds that it is not only necessary to study the variables that are defined a priori, but also to

analyze the variables taken into account by the actors in the action. Several authors (Lenoir, Larose, Deaudelin, Kalubi, & Roy, 2002) and Lenoir (2009) encourage considering educational intervention as “benevolent interaction”. Following the conceptual analysis, they demonstrate that the educational intervention is multidimensional, associating didactic, psycho-educational, organizational and institutional and social dimensions. The authors explain that the educational intervention is based on a device integrated into the situation that is designed as a transitional space promoting the learning process. Thus, the device is nothing other than the place of interaction between two types of mediations constituting the teaching-learning relationship. The cognitive mediation for which the subject is responsible to establish with the student and the pedagogic-didactic mediation under the responsibility of the teacher, this mediation is qualified as an educational intervention. The intervention is adopted from a practical-interactive point of view. Classroom management is increasingly appearing at the “heart of the teacher effect” (Martineau, Gauthier, & Desbiens, 1999), student learning depends on it and is not limited solely to didactic dimensions. Classroom management competence turns out to be a complex, dynamic and multidimensional activity (Legoult, 1999). Chouinard (1999) asserts that academic success is mainly influenced by classroom management and that the effectiveness of the latter optimizes the time devoted to learning and ensures the smooth running of educational activities. So, therefore, you have to manage your classroom in such a way as to meet the needs of the learners. According to Lacourse (2012), taking professional routines as a guide for daily action in the classroom and identifying the characteristics is essential for any teacher who intends to take a reflective look at his classroom management. Once these routines are installed and successful, the teacher can focus his attention on the knowledge to be built with the students. Léveillé and Dufour (1999) attempted to identify the main difficulties in classroom management for teachers working in secondary school. They conclude that effective management is not only based on disciplinary management of the classroom but extends to good planning of instructional content that responds to the real needs of learners and takes into account the individual differences of students. Lessard and Schmidt (2011) argue that the teacher must strike a certain balance between several tasks and functions to be able to actually help the student to develop his skills. The teacher must take into consideration the class group but also individual differences, he must also allow the cognitive and socio-emotional development of the students, he must promote and maintain a climate conducive to learning while using pedagogical approaches fulfilling the various student needs. The action of the PE teacher, during his daily professional practices, has two primary aims of a didactic and pedagogical nature (Doyle, 1986; Gal-PetitFaux & Vors, 2008; Leinhardt, 1990; Shulman, 1986a, 1986b). A goal of building knowledge and know-how among students on the one hand, a goal of management and organization of the class, on the other hand, coordination and complementarity are mandatory between these two goals (Gal-PetitFaux & Vors, 2008). Is the percentage of the distribution of these two sights along the learning situations or even the length of an PE session equal for all teachers? Does this percentage fluctuate depending on the situation or the gender of the teacher?

2. Methodology

To answer these questions, we worked with 30 PSE teachers. They are divided into 15 men and 15 women. The criterion of volunteering was essential here and the participants were all informed in advance of the framework and conditions of the research. To make this study a reality, we used two investigative techniques: first, we proceeded by video recording the gymnastics sessions at the rate of two sessions per teacher. These sessions lasted an average of 55 minutes. The teachers’ interventions were filmed in situ, using three digital cameras, one of which is placed on the teacher’s head allowing him total freedom of movement, in order to collect all verbal communications and all the angles targeted by the teacher. A second camera is handled by the researcher who follows all the teacher’s movements at a respectable distance, thus guaranteeing wide shots capturing all the teacher’s interventions with his students. A third camera mounted on tripods in a corner of the gymnasium provides very wide framing shots, allowing constant viewing of the teacher and all students. Secondly, 2 interviews with each participant were recorded: following the progress of the first session, a semi-structured interview is carried out and recorded, thanks to a tape recorder, with each teacher filmed, in order to collect, as a first step, the conceptions, who are the PE teachers of the dynamics of teaching practices during gymnastics sessions. Self-confrontational interviews, which serve to document the actor’s pre-reflective experience (Theureau, 1992), were carried out immediately after the conduct of the practical sessions. A laptop computer and a video projector allowed the viewing and projection of the videotape of the recorded lesson. A tape recorder enabled the audio recording of the post-lesson interviews. Playback of the videotape is interrupted by the pause, advance, return functions at any time at the request of the teacher or the researcher. The teacher is confronted, at every moment, with his actions to which he is invited, by semi-open questions and based on the video, to explain what he was doing, thinking, taking into account in order to act, perceived, felt (Vermersch, 1994), without asking for justifications. For the data processing we started with the transcriptions of the semi-structured interviews and the self-confrontation. We then transcribed the practical sessions in the form of a two-part table, for part 1 actions of the teacher and students and for part 2 verbatim of the teacher. In a second step, we submitted the verbatim recordings as well as the responses of the two interviews to the content analysis technique in the form of grids containing the statements and the achievements. In the last step, we submitted the collected data to statistical processing using SPSS software where we applied the chi-square test and we also used the calculation of percentages for well-defined data.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Representations and Achievements of Teachers According to Their Gender with Regard to the Dynamics of Gymnastics Sessions

We submitted the results obtained from the semi-structured interviews and the data collected through the self-confrontation interview and the analysis of video tapes of the practical sessions, classified according to the teacher’s gender, on the Chi-square test. The results obtained are collated in Table 1.

From Table 1 there is a very significant difference between the statements of male and female PE teachers about the dynamics of gymnastics workouts. Women say they favor the organization while men say they favor the technical aspects. On the other hand, in the field there is no significant difference between the management of the practical sessions to the detriment of the gender of the teacher. The teachers take care to guide learning in good organizational conditions.

In terms of beliefs, women say they favor the educational component while men say they favor the didactic component. Practically the teachers use the same strategy of exploiting a three-dimensional material-space-time educational device to succeed in the conduct of learning in the students. The representations made by PE teachers on the dynamics of the practical teaching session are modulated according to the gender of the teacher. The latter does not influence the dynamics of the session (Table 2).

3.2. Representations and Achievements of Teachers According to Their Gender with Regard to Their Pedagogical Management of Gymnastics Sessions

We submitted the results obtained from the semi-structured interviews and the data collected through the self-confrontation interview and the analysis of the video tap, practical sessions, classified according to the teacher’s gender, on the Chi-square test. The results obtained are collated in Table 3.

According to Table 3, there is a very significant difference between the statements of male and female EPS teachers about the pedagogical management of the session. According to teachers’ statements, women place more importance on organizational and relational aspects than men. However, in the field, there is no significant difference between the pedagogical management of the class to the

![]()

Table 1. Distribution of statements and achievements according to the gender of the teacher.

![]()

Table 2. Testimonies of the representations and achievements of teachers according to their gender with regard to the dynamics of gymnastics sessions.

![]()

Table 3. Distribution of statements and achievements of teachers according to their gender about their pedagogical management of the PSE session.

detriment of the teacher’s gender. The teachers, male or female, have had recourse to the management of the class thus trying to move the minimum of material to save time.

In their statements about pedagogical management, female teachers pay more attention to organizational, relational and security aspects, while men focus more on saving time for learning. Practically, female teachers as well as men teachers use the same strategy of exploiting materials and cues as cognitive artefacts to save time and space and convey knowledge content to students. Teachers favor the “workshop” pedagogical format arguing that this pedagogical format facilitates work and engages the whole class, using groups of levels, and allows the teacher to control all the students. There is a difference in the representations of educational management depending on the gender of the teacher. On the other hand, practically the genre does not intervene (Table 4).

3.3. Representations and Achievements of Teachers According to Their Gender with Regard to Their Didactic Management of Gymnastics Sessions

We submitted the results obtained from the semi-structured interviews and the data collected through the self-confrontation interview and the analysis of the video tape, practical sessions, classified according to the teacher’s gender, on the Chi-square test. The results obtained are collated in Table 5.

![]()

Table 4. Testimonies of the representations and achievements of teachers according to their gender with regard to the pedagogical management of gymnastics sessions.

![]()

Table 5. Distribution of statements and achievements of teachers according to their gender regarding their didactic management.

According to Table 5, there is a very significant difference between the statements of male and female PE teachers about the didactic management of the session. According to teachers’ statements, men are keen to devote most of the time to guiding learning without worrying too much about the organizational side of the lesson. The latter is privileged by women and it is considered as an essential criterion for the success of learning, it is necessary to organize well to succeed the session if not the session fails. In the field, there is no significant difference between the didactic management of the class to the detriment of the gender of the teacher, despite a big difference in their statements. The male and female teachers focus during their session on the success of the student’s learning and especially on the gymnastic sequence at the end of the session.

At the level of beliefs, female teachers attach importance to the organizational conditions in which learning takes place without neglecting the latter. On the other hand, male teachers say they are more technical. From a practical point of view, both female teachers and male teachers, during their practical actions during gymnastics sessions, develop the same intervention strategy after the warm-up phase, they introduce differentiated learning from a new technical gymnastic element and towards the end of the session, the new element must be linked with the rest of the elements, already learned during the previous sessions, to reproduce a gymnastic sequence. Teachers use the binding moment of the practice for correction, as well as, to work on the rhythm and aesthetics of the movement. The teachers, men and women, insist on the aesthetics of gesture for girls and strength training for boys. There is a difference in the representations of didactic management depending on the gender of the teacher. On the other hand, practically the genre does not intervene (Table 6).

3.4. Detailed Analysis of Teaching Practice: The Regularities of Intervention

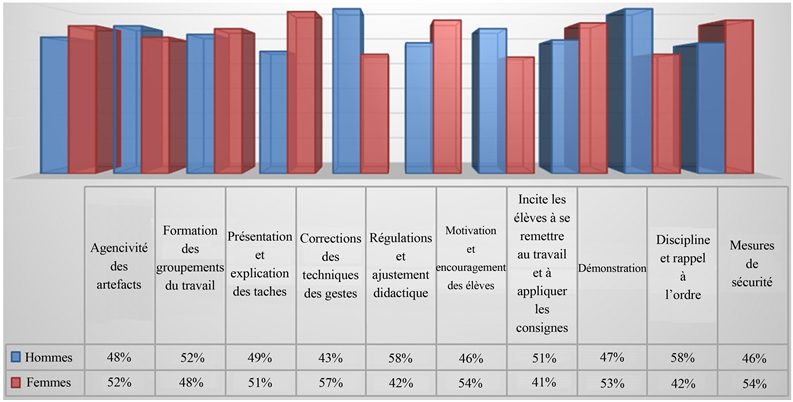

We have deepened our research into the details of teaching practice. We calculated the percentages at the levels where teaching practice represents a regularity of intervention for all teachers. The following Diagram 1 summarizes the results obtained.

According to the diagram, female teachers handle the equipment, secure the premises, demonstrate technical skills and they motivate the students more than the men. On the other hand, the male teachers bring more regulations and didactic adjustments and they manipulate more the dispositions and the groupings

![]()

Table 6. Testimonies of the representations and achievements of teachers according to their gender with regard to the didactic management of gymnastics sessions.

Diagram 1. Percentages of intervention regularities by the PE teacher.

of the pupils. Even if the teachers have, overall, developed the same strategies for the conduct of the gymnastics session, in depth there are qualitative differences for the regularities of intervention marked by the gender of the teacher.

4. Discussion

The main results of this study tend to show that teachers put forward different representations about their teaching practices, except that in practice, they present stable forms and common strategies that the dynamics of activity in the classroom can take. So, we notice a gap between the representations of teachers but the absence of a gap between their achievements in the field, our results corroborate with the work of some researchers. Nault and Fijalkow (1999), find it difficult to move from idealistic representation to everyday practice. For Boizumault and Cogérino (2012), contradictions appear in the statements about initial beliefs when teachers see themselves in action confronted with the video of the practical session. According to Piot (1997), there is no such thing as a “typical” teacher and that teachers’ representations of their practices and pedagogical conceptions are of a composite nature, thus preventing teachers from being considered as a “homogeneous whole”.

In the field there is no difference between the management of the class of female teachers and that of men, despite a big difference in their statements. Our results do not corroborate with the results of some previous research that dealt with this concept of classroom management in relation to the gender of the teacher. Roux-Perez (2004) underlines a difference in the characteristics of PSE teachers according to sex, asserting, as well as according to men, the ideal profile of the teacher is to master the taught activity and to be a technician. While for women the main reasons that lead them to choose this profession is the desire to be a teacher and success in PSE. For Couchot-Schiex (2005), gender and sex are deeply intertwined, so that in some situations gender is predominantly expressed, while in others sex wins out. The demonstration of authority is predominated by gender and is in favor of men by their manner of asserting themselves physically (mainly addressed to boys), while student control is still used more by women by adapting means of control less visible and more diverted (sanctions or threats). a lot of times the author (Couchot-Schiex, 2007a, 2007b), confirms that threats are addressed, rather to boys by all teachers, despite her claim that most female teachers wish not to be authoritarian and above all they avoid playing the role of “gendarme” but rather they use roundabout forms and means to control their classes like loving relationship or physical closeness.

The results of the analysis focused on the gender of the PE teacher and the way in which he operates the management of taught content do not show any significant effect and they show consistency with previous research. Couchot-Schiex (2005) asserts that, during PSE sessions, gender and sex combine in a compensatory effect for learning content and that the teacher’s gender influences the content transmitted as well as the process of its transmission, On the other hand, gender affects aspects of verbal and non-verbal communication. (Couchot-Schiex, 2007a, 2007b) asserts the results, regarding learning content to the detriment of the gender of the PE teacher, remain inconclusive. The learning contents are marked by heterogeneity and they differ from a large inter-individual variability. In the course of their practices, the teachers differ markedly according to the sex of the student, they demand aesthetics and harmony for the performance of the girls, on the other hand, the boys are asked to rise to the challenge and to take risks. In gymnastics, women remain more vigilant about the safety and assistance of the student, which reveals female stereotypes.

5. Conclusion

The results obtained are modulated here by two major variables; declared and realized. Each of these broad variables can be broken down into the gender of the teacher. Indeed, the statements collected through the first semi-directive interview are affected by the gender of the teacher. Teachers report being more concerned with the organization and its relationships in the classroom than teachers. On the other hand, men say they are more technical than women. In addition, the data collected through the self-confrontation interview and the analysis of the videotapes of the practical sessions show that for the “Realization” aspect that the teachers of the present study respect the teacher’s mission in his two complementary components, pedagogical, organizational and relational management, and didactic management of learning content. During their practical actions during gymnastics sessions, teachers develop the same intervention strategies. Practically the teachers use the same educational device with three dimensions, material-space-time to succeed in the conduct of learning in the pupils. They choose the particular educational format of workshop work. This configuration was able to induce the teacher to save time, an activity of supervision and control, a differentiation of the content of the work and the investment of the students according to their individual skills thus guaranteeing their successes. The construction of a work environment in PE carries educational potential. The teachers differentiate the learning of technical elements according to the levels of the students and then they lead the students to reproduce a gymnastic sequence. The intervention strategies during the practical sessions of the gymnastic activity are marked by regularity and typicality.

6. Outlook

Like all research, ours has limits. We retained floor gymnastics as the only physical and sports activity (PSA) taught in this study. We can take into consideration other PSA taught in the school environment. Therefore, we will be able to compare the intervention strategies of teachers in different PSA without forgetting the effect of the female or male connotation of the PSA taught. In the present work, we have focused only on the gender of the teacher thus neglecting the other actor in the teaching-learning situation, the pupil. We can broaden our investigation by crossing the gender identity of the teacher with that of the student to verify the impact of this crossing on the success of the student. These limits may present an extension for future research.