Conversion of 3,4-Dihydroxypyrrolidine-2,5-Dione to Maleimide through Tosylation and Mechanism Study by DFT ()

1. Introduction

Pyrrolidine-2,5-dione and maleimide exist in numerous organic substances and are common scaffolds of many important chemicals, drugs, nutrients, dyes, materials, etc. They are readily prepared through condensation reactions of succinic acid or maleic acid or their chiral derivatives (like tartaric acid, malic acid, etc.) with primary amines without racemization, and therefore are important building blocks in organic synthesis, especially in asymmetric synthesis [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] . Specifically because of their promising biological activities, derivatives of pyrrolidine-2,5-dione and maleimide are receiving more and more attentions from researchers in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] . Tosyloxy (p-toluenesulfonyloxy, -OTs) is an important functional group in organic synthesis because it is a very good leaving group (even better than iodide) [11] and may be conveniently prepared through tosylation of alcohols without affecting the stereochemistry. However, substances bearing a tosyloxy group on pyrrolidine-2,5-dione or maleimide are very rare. As of June 19, 2018, only 1 substance (with 1 patent, CAS RN 129282-11-7 [12] ) bearing the substructure 3-tosyloxypyrrolidine-2,5-dione had been reported; and for substructure 3-tosyloxymaleimide, only 2 substances (with 2 literatures, CAS RN 903578-02-9 [13] and 873939-14-1 [14] ) had been reported. In our study, we planned to introduce tosyloxy functional groups to pyrrolidine-2,5-dione and maleimide scaffold in order to synthesize novel substituted pyrrolidine-2,5-diones and maleimides. We were surprised to discover that (3 R, 4 R)-3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidine-2,5-dione (L-tartarimide) tosylates may spontaneously lose a TsOH molecule to form monotosylated maleimide. Theoretical computation was then performed using density functional theory (DFT) to study the possible mechanism of this reaction; the results showed that the L-tartarimide monotosylate was thermodynamically instable and may eliminate a TsOH molecule to form the maleimide scaffold. The kinetic factors were also examined and it was concluded that this elimination is primarily driven by thermodynamic factors.

2. Results and Discussion

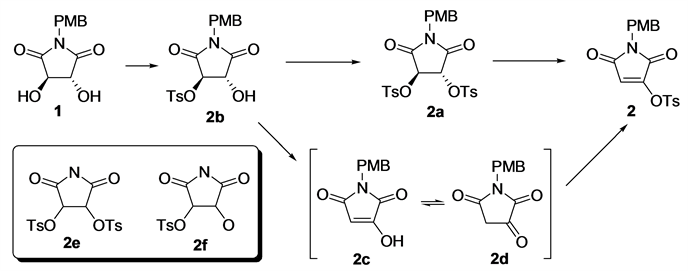

In our studies, L-tartaric acid was firstly condensed with p-methoxybenzylamine (PMB-NH2) to form intermediate 1 (Scheme 1), according to the method in the literature [1] . 1 was then subject to tosylation by TsCl and Et3N at room temperature to furnish ditosylated intermediate 2a, which was to be used in synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted pyrrolidine-2,5-dione through nucleophilic substitution in our plan. Surprisingly, neither the ditosylated product 2a nor the monotosylated product 2b was found; instead, the tosyloxymaleimide 2, which is obviously a product after eliminating a p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH) molecule, was obtained in high yield (85.2%).The 1H NMR spectra of 1 and 2 are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

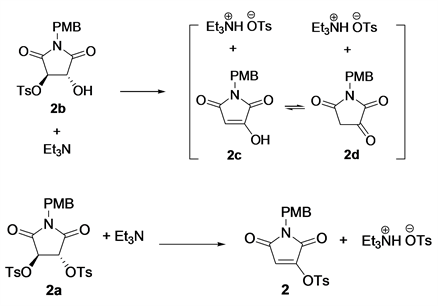

Obviously, there are two possible processes for such a conversion (Scheme 2): 1 might be ditosylated to form intermediate 2a, which then loses a TsOH molecule

Scheme 1. Reactions and conditions: (a) xylene, Dean-Stark apparatus, reflux, 12 hr; (b) TsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0˚C ~ rt, overnight.

Scheme 2. Possible reaction processes from 1 to 2.

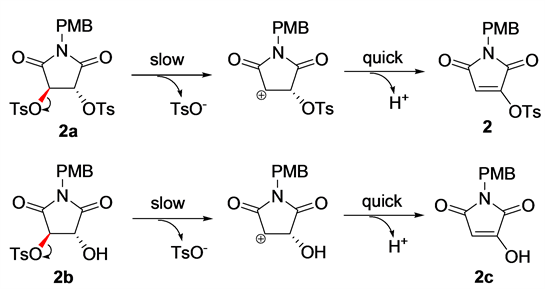

to give 2; alternatively, the monotosylated intermediate 2b might lose a TsOH to form the enol-ketone tautomers 2c and 2d, which were then tosylated to give 2. Substructure search with SciFinder showed that none of the structure 2e and 2f, nor any compounds bearing 2e or 2f as a substructure, have been reported so far. Therefore, we proposed that the monotosylated or ditosylated derivatives of trans-3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidine-2,5-dione might be (thermodynamically and/or kinetically) instable and easily to undergo elimination reactions spontaneously.

The free energy discrepancies between the reactant and product of this elimination were evaluated for both 2a and 2b by DFT with Gaussian 09 [15] (Table 1). The reactants and products were firstly geometrically optimized with hybrid-meta GGA functional M06-2X [16] [17] and the basis set6-31G** [18] [19] , followed by frequency analysis at the same computational level, to give the thermal correction values to Gibbs free energy. Finally, the optimized structures were recalculated for single point energy (ε) using double-hybrid functional B2PLYP [20] and def2-TZVP basis set [21] [22] . (All DFT calculations in this work were done with SMD implicit solvent model [23] of dichloromethane, the actual solvent of the reaction.) The Gibbs free energies were then calculated by summing up ε with the thermal correction values. As shown in Table 1, great free energy discrepancies between 2b and 2c/2d (−147.7 and −157.0 KJ/mol, respectively) indicated that 2b is thermodynamically instable and tend to release a p-toluenesulfonic acid to give 2c or 2d, especially in the presence of triethylamine. Similarly, 2a is also apt to convert to 2, although the free energy discrepancy is considerably smaller (−82.0 KJ/mol).

![]()

Table 1. Possible intermediates in the conversion of 1 to 2 and Gibbs free energies calculated by DFT.

a)Thermal correction values were calculated at M06-2X/6-31G** level with the frequency scale factor of 0.9670 [24] at 298.15 K. ε values were calculated at B2PLYP/def2-TZVP level. All energies were in Hartree.

![]()

Table 2. Bond lengths, bond orders and relaxed force constants of the C-OTs bond cleaved in E1 elimination of 2a and 2b.a)

a)Geometry optimization and vibration analysis of all structures were at M06-2X/6-31G** level. b) Because the optimal conformation of 2a has no C2 symmetry, the two C-OTs bonds, marked (1) and (2) here, have slightly different properties.

Scheme 3. E1 elimination mechanism of 2a and 2b.

stability of the elimination products, primarily contributed by the formation of a large conjugation system, would promote the E1 elimination. Considering the significantly greater free energy change of 2b than 2a during the elimination, and the fact that no substances bearing substructure of 2f have been reported, we concluded that this elimination reaction was more likely to take place at monotosylated stage; i.e., the reaction process should be 1 → 2b → 2c/2d → 2.

It is also worth mentioning that, the free energy difference between (2c + Et3N・HOTs) and (2d + Et3N・HOTs) (9.3 KJ/mol) indicated that the ketone form (pyrrolidine-2,3,5-trione) is thermodynamically more preferable than the enol form (3-hydroxymaleimide), agreeing with common knowledge. According to the Boltzmann distribution, the approximate ratio of 2c: 2d was calculated to be 2.3%:97.7%, the ketone form being the predominant. However, the free energy difference of 9.3 KJ/mol is not very large, otherwise the reaction would stay at 2d, without forming 2c and 2.

3. Conclusion

In this study, the application of tosyloxy (-OTs) group on two important scaffolds, pyrrolidine-2,5-dione and maleimide, was explored. Few compounds or studies have been reported in this area so far. We discovered that, upon tosylation by TsCl/Et3N, (3 R, 4 R)-3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidine-2,5-dione (L-tartarimide) could convert to monotosylated maleimide, instead of monotosylated or ditosylated pyrrolidine-2,5-dione. Theoretical computation studies using DFT demonstrated that, the intermediate 2b (a monotosylated pyrrolidine-2,5-dione) will eliminate a TsOH molecule spontaneously to form a pair of enol-ketone tautomers, which was then tosylated to give 2 (monotosylated maleimide). DFT calculations also showed that such an elimination reaction was due to thermodynamic reasons rather than kinetic reasons; tosylates of trans-3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidine-2,5-dione are thermodynamically instable and liable to convert to maleimides. This might help to explain why so few (only one) tosylated pyrrolidine-2,5-dione substance had been known before. We hope this study will be helpful in broadening the understanding of the chemical and reaction properties of pyrrolidine-2,5-dione and maleimide, as well as in the organic synthesis involving such scaffolds. The related synthesis studies on tosylated maleimides are ongoing and will be reported soon.

4. Experimental Details

4.1. Chemical Synthesis

General methods: L-tartaric acid, PMB-NH2, and TsCl were purchased from Aladdin Chemical Reagents (Shanghai, China). Other reagents were from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). The boiling range of petroleum ether is 60˚C - 90˚C. Analytical TLC was performed with pre-coated silica GF254 plates (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical, Qingdao, China) and visualized by UV radiation (254 nm). NMR spectra were determined on Bruker AscendTM 600 spectrometers. HRMS was recorded on Bruker Daltonics maXis UHR-TOF with ESI ionization source.

1) Synthesis of (3 R, 4 R)-3,4-dihydroxy-1-(4-methoxybenzyl) pyrrolidine-2,5-dione (1).

L-tartaric acid (15.00 g, 100 mmol) was suspended in xylene (160 ml) in a three-necked round-bottom flask equipped with a Dean-Stark apparatus, to which PMB-NH2 (13.0 ml, 100 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred and heated to reflux for 12 hours, during which additional xylene (40 ml) was added. The mixture was cooled down to room temperature and filtered. The filtration cake was washed with cold dichloromethane to give 1 (21.38 g, 85.1 mmol) as a white powder. Yield: 85%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): 3.72 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.34 (m, 2 H, H-3, H-4), 4.46 (1 H, d, J = 14.4, NCH2), 4.50 (1 H, d, J = 14.4, NCH2), 6.27 - 6.30 (m, 2 H, OH), 6.87 - 6.90 (m, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.18 - 7.20 (m, 2 H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): 41.1 (NCH2), 55.6 (OCH3), 74.9 (C-3, C-4), 114.4, 128.5, 129.7, 159.1 (Ar-C), 175.0 (C-2, C-5). The analytical data of the product agreed with the literature [1] .

2) Synthesis of 3-tosyloxy-N-(4-methoxybenzyl) maleimide (2).

1 (6.80 g, 27.1 mmol) was suspended in CH2Cl2 (160 ml) in ice bath, to which TsCl powder (15.50 g, 81.3 mmol) was added slowly. The reaction mixture was stirred in ice bath and Et3N (11.2 ml, 81.3 mmol) was added drop by drop. After completing adding Et3N, the ice bath was removed and the mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction was then quenched by adding water. The two-layer mixture was separated, and the water layer was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic phase was combined, washed with water for 3 times, and concentrated in vacuum. The obtained residue was reslurried in petroleum ether to give a dark red powder, which was then recrystallized in CH2Cl2-Et2O to furnish 2 as a white powder (8.96 g, 23.1 mmol). Yield: 85.2%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): 2.47 (s, 3 H, PhCH3), 3.76 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 4.54 (s, 2 H, NCH2), 6.23 (s, 1 H, H-4), 6.79 - 6.82 (m, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.22 - 7.24 (m, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.38 - 7.40 (m, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.86 - 7.87 (m, 2 H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): 21.9, 41.1, 55.3, 109.2, 114.0, 127.9, 128.7, 130.1, 130.4, 130.9, 147.3, 149.2, 159.4, 164.0, 168.1; HRMS m/z: [M + NH4]+ calculated 405.1115, found 405.1112; [M + Na]+ calculated 410.0669, found 410.0668.

4.2. Theoretical Computation

All DFT calculations were done with Gaussian 09 with SMD implicit solvent model of CH2Cl2. Structure models of molecules were subject to geometry optimization in Gaussian 09 using M06-2X functional and 6-31G** basis set. Vibration analysis was at the same level to geometry optimization, and no imaginary frequencies were found for any structures. The frequency scale factor of 0.9670 was used in calculation of thermal correction value to Gibbs free energy. After geometry optimization, single point energy was calculated at a higher computation level (B2PLYP functional with def2-TZVP basis set), which was then added to the thermal correction value to obtain the Gibbs free energy. Bond order and relaxed force constant of bonds were analyzed by Multiwfn 3.5 and Compliance 3.0.2, respectively, after geometry optimization and vibration analysis at M06-2X/6-31G** level.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Science and Technology Plan Project of Universities and Colleges of Shandong Province (J17KA260), The Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2016BL05), and funding programs of Jining Medical University (Support Funding JY2016KJ002Z, and Doctoral Funding JY2015BS16).