The Effect of Cancer Diagnosis Disclosure on Patient’s Coping Self-Efficacy at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia ()

1. Introduction

Worldwide in 2018 WHO reported around 18 million newly diagnosed cases with cancer. The incidence rate of age for people diagnosed with cancer was 25% higher among male more than female [1] . In Saudi Arabia, The total number of newly diagnosed cancer patients reported by the Saudi Cancer Registry (SCR) in 2014 was 15,807. Numbers showed that women were affected more than men 7462 (47.2%) males and 8345 (52.8%) females [2] .

The effect of cancer diagnosis is still controversially shocking. Many literature suggest that patients are challenged and had difficulties in disclosing a cancer diagnosis with their family members or friends. Other studies reported that sharing cancer diagnosis disclosure with families and friends had improved their psychological and social well-being [3] .

Non-western countries still consider patients’ opinions and choices about cancer diagnosis disclosure as one of the major topics to discuss. In Asia and Middle East cancer diagnosis disclosure is difficult for patients, and their health care providers due to cultural backgrounds and family involvement which makes cancer disclosure difficult and traumatic fact to be shared with patient’s family and friends [4] .

A Saudi study reported that the attitude towards cancer diagnosis disclosure in Saudi society still conservative due to cultural and religious factors. However, (97%) of Saudis in a sample of (420) cancer patients wanted cancer diagnosis to be fully disclosed, and none of them wanted cancer diagnosis disclosure to be hidden. Knowing, that the majority of patients preferred not to share their cancer diagnosis disclosure with own families [5] . Other Eastern culture results were similarly reported in a Chinese study which showed that (85%) of the patients wanted to be fully disclosed about their diagnosis, and only (15%) wanted to be partially disclosed [6] .

Patient lack of information sufficiency was addressed in different studies. 90% of Saudi cancer patients preferred to be part of their treatment plan and care regardless of their age, or education level. Also, three-quarters of the Chinese families did not understand the diagnosis, and the information related to it in a study done on (266) Chinese cancer patients, and their families. Inability to define cancer diagnosis disclosure and lack of knowledge make the patients and their families overestimate negative possibilities [5] [6] . Patients and families need to be empowered to cope effectively and developed a coping self-efficacy that allows them to manage diagnosis and treatment modalities.

1.1. Aim of the Study

To assess the effect of cancer diagnosis disclosure on patient’s coping self-efficacy at King Abdulaziz University Hospital.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

The authors selected the coping self-efficacy theoretical framework to pave the research. Developed and tested by Bandura A. [7] Coping self-efficacy (CSE) is defined as “individuals’ self-appraisal of their ability to manage and cope with situational demands”. CSE may influence individuals’ reactions to stress and behavioral outcomes. An individual’s belief in his or her efficacy influenced by four main ways which are: Mastery experiences, observational learning, social persuasion, and emotional arousal which can be seen as anxiety. Others defined Coping self-efficacy (CSE) as “it is the perceived ability of a person to meet the demands of coping with traumatic life experiences”. CSE is an important part of patients’ psychological adjustment [8] .

Several quantitative studies had tested its reliability in assessing coping and self-efficacy, Philip, Merluzzi, Zhang, and Heitzmann (2013) reported that cancer survivors benefited from CSE and the results showed that assessing cancer patients at the time of diagnosis for CSE could be predictive of disease and psychological adjustment. If the patient’s ability to cope fails using maladaptive this may lead to poor psychological adjustment [9] [10] .

In other qualitative study conducted where six families-caregivers interviewed, revealed that Nurses are not considering those very important emotional events lived by patients and their family members. Providing enough emotional support and adequate information are critical to develop coping skills. Thus, Nurses should initiate a process of communication and support with cancer patients and their families [11] [12] .

Since cancer diagnosis disclosure is still a challenge for patients and health care providers in Saudi Arabia which may affect the patient’s ability to cope with a cancer diagnosis and it is subsequent treatments. And nurses know very little about the effect of disclosure of cancer diagnosis on patient’s coping self-efficacy. This study aimed to assess the effect of cancer diagnosis disclosure on patient’s coping self-efficacy at King Abdulaziz University Hospital.

CSE beliefs can be a significant predictor of Post traumatic distress (PTSS) where participants with higher CSE beliefs have less PTSS. (Figure 1) [13]

![]()

Figure 1. Conceptual model, proposing pre-event factors may affect post-event factor Coping self-efficacy (CSE), predicting that the higher pre-event general self-efficacy (GSE) and perceived social support the higher CSE, thus lower PTSS through CSE. PTSS: Posttraumatic stress symptoms.

[14] . Based on CSE and the theoretical framework presented above, the current study assessed whether there is a relationship between disclosure of cancer diagnosis and coping self-efficacy or not.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

Descriptive cross sectional design, using multivariate statistical approaches to assess the effect of cancer diagnosis disclosure on patient’s coping self-efficacy.

2.2. Settings

This study was conducted at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, sample recruited from inpatient Surgical and gynecology units and day care unit.

2.3. Sample

A convenient sample matching the inclusion criteria was selected, structured questionnaire interview was used. (102) participants and who had fully agreed voluntarily to fully disclose the effect of cancer diagnosis were included in this study.

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

1) Adult aged above 18 years old;

2) Relatively newly diagnosed patients about two years since diagnosed with cancer;

3) Patient with Stage I, II, and III of cancer. Terminal and metastatic cases were excluded.

2.5. Ethical Consideration

This research was approved by faculty of nursing ethical committee and King Abdulaziz University Hospital ethical committee. Consent forms were provided to all participants after explaining the aim of the study, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality of their information and their full right to withdraw at any time.

2.6. Tools

The data for this study were collected by using one tool divided into two parts:

Part I: Socio-demographic developed by the researchers, Including age, gender, marital status, and city, and nationality, level of education, family income, and time of diagnosis;

Part II: Structured interview questionnaire using coping self-Efficacy Scale (CSE) developed by Margaret A. Chesney, Torsten B. Neilands, Donald B. Chambers, Jonelle M. Taylor and Susan Folkman [15] . It consisted of 26 items subdivided into three factors which are: Use problem-focused coping (12 items), stop unpleasant emotions and thoughts (9 items), and get support from friends and family (5 items).

Scoring: An overall CSE score is created by summing the item ratings “α = 0.95; scale mean = 137.4, SD = 45.6” [16] . The mean of the items was calculated and then multiplied by the number of the scale items. Knowing that, the participants have answered 80% at least of the scale items.

Validity: The English version of coping self-efficacy scale was translated into Arabic, back translated and reviewed by 3 experts from nursing faculty to check for accuracy and clarity. Comments and suggestions were considered and in order to minimize the patients’ stress during the survey the word “disease” was used instead of “cancer” throughout the interview.

Reliability: The originally reported reliability of the scale is α = 0.95. The calculated reliability of the scale after translation into Arabic was α = 0.84. Both measured via Chronbach’s α.

Pilot Study: 10% of the selected samples were tested and provided a questionnaire to ensure accuracy, clarity, feasibly, and time required to fully fill the coping self-efficacy scale after the translation into Arabic.

2.7. Procedures

Participants were selected from King Abdulaziz University Hospital by approaching nurse managers of the selected units and providing them with a copy of the ethical approval of the study, a brief overview about the study, eligibility criteria, and research team contact information.

The selected participants were approached by the research members and had an explanation about the aim and the meaning of the research. Participants provided with a package containing a consent form, contact information of the research team, and two papers of six multiple choices anonymous questionnaires.

118 participants were approached, but only 102 were eligible for this study. The rest 16 were unable to complete the questionnaire due to the involvement of procedure and treatment interruptions (4), Refusal of completion (6), Refusal of patients or family members (5), and other nationalities that were unable to understand Arabic or English (3). This study started in September 2017 and finished in August 2018.

2.8. Data Analysis

The data of this study were coded and captured electronically into (SPSS a statistical package for social sciences version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A statistician was consulted in some of the elements of data analysis.

3. Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants (n = 102) are shown in (Table 1). The table showed that study participants age of 41 years old and above have the highest percentage (71.3%), where age category ranged between 18 - 30 years old have the lowest percentage (7.9%). About three-quarters of the participants (66.7%) are female and (33.3%) are male. Married participants have the highest percentage (79.4%). Most of the participants were Saudis

![]()

Table 1. Socio-Demographic characteristics of the study participants’ (n = 102).

in comparison to non-Saudis, the percentages were (56.9%) and (43.1%) respectively.

Educational level varies from primary to post graduate level, a university graduate accounted for (39.4%). Percentages for secondary and primary levels were (24.5%) and (21.3%) respectively. (13.8%) completed intermediate level and (1.1%) attained post graduate level. Most of the participants have an average income level with a percentage of (78.4%). Where (14.4%) of them were less than average, and (7.2%) accounted for higher than average.

On the other hand, (Table 2) showed the diagnosis time profile of the study participants. The maximum duration since cancer diagnosis disclosure is two years. (23.8%) of the participants were diagnosed two years ago (45.5%) were diagnosed one year ago, (22.8%) were diagnosed one month ago, and (7.9%) were diagnosed two weeks ago at the period of data collection.

(Table 3) shows the CSE scale items’ means, and standard deviations. As well as the overall mean for all CSE items, and overall CSE Scale score. It showed that most of the study participants perceived moderate certainty in 21 items listed in (Table 3). The study participants perceived higher certainty in getting emotional support from friends and family, find solutions to their most difficult problems, try other solutions to their problems if their first solutions don’t work, and pray or meditate. However, results showed that participants tend to believe that they

![]()

Table 2. Diagnosis time profile of the study participants’ (n = 102).

![]()

Table 3. Total mean distribution of Coping Self-Efficacy scale items of the study participants’ (n = 102).

cannot get emotional support from community organizations or resources. Lastly, the overall mean of the study participants’ perception was moderate coping self-efficacy (3.86 ± 0.552), with the score for the scale (100.60 ± 14.370).

Participants were moderately able to use problem-focused coping and get support from friends and family. However, about half of them (47.1%) showed certainty in stopping unpleasant emotions and thoughts (Table 4).

There was no significant relationship between social-demographics and coping self-efficacy (Table 5), where p-value higher than 0.05.

Lastly, to find out the relationship between diagnosis time with coping self-efficacy of the study participants’ (Table 6) showed that no significant relationship, where p-value was higher than 0.05, as no differences in CSE among participants who were diagnosed with cancer within two weeks ago, one month ago, one year ago, or two years ago.

![]()

Table 4. Total mean distribution of Coping Self-Efficacy subscale categories of the study participants’ (n = 102).

![]()

Table 5. The relationship between Socio-Demographic characteristics and Coping Self-Efficacy scale of the study participants’ (n = 102).

*Kruskal Wallis Test: p-value significant at 0.05.

![]()

Table 6. The relationship between diagnosis time with Coping Self-Efficacy scale of the study participants’ (n = 102).

*Kruskal Wallis Test: p-value significant at 0.05.

4. Discussions

It is assumed that most cancer patients are unable to adjust to their new traumatic experience. However the given study showed No significant relationship between cancer diagnosis disclosure and patients’ coping self-efficacy. Also, none of the other Socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, city, nationality, level of education, and income had significant relationship with the effect of cancer diagnosis disclosure. Knowing that most of the cancer patients included in this study had moderate coping self-efficacy scores regardless of the time they had been disclosed at. This may be explained by the strength of the Middle Eastern cultural ties, social structure and spiritual factors.

Irrespective to the significance of the study, the use of coping self-efficacy scale was useful to negate the assumption that most of the cancer patients were unable to adjust to a cancer diagnosis. Philip (2013) reported that the scale could be used as a tool to assess the individual’s ability’s to cope and thus enhance survivorship through implemented psychological interventions, and therefore assessing Coping self-efficacy upon disclosure of a cancer diagnosis can be predictive of long term psychological adjustment. Nursing strategies will be geared towards easing both physical and psychological distress.

Munro et al. (2015) reported different clinical and social factors that have an impact on the disclosure of cancer diagnosis, in a sense that it is the way of communication with the patients and make them more willing to receive information, clarifications, and able to express their emotions. Which in line with the current study findings, where three-quarters of the participants were married and most of the participants were able to manage and stop unpleasant thoughts, and moderately able to get support from family and friends. Budziareck das Neves et al. (2017), Ali M Al-Amri (2013), Munro et al. (2015) concluded that Nurses are the main providers of physical and psychological support to all patients, it is the nurse’s essence of care to take into account those delicate moments lived by cancer patients and their family upon disclosure of cancer diagnosis, and use them appropriately to provide needed information and construct a sensitive cultural, social and religious plan of care.

5. Conclusion

This study reveals that there is no significant relationship between the effect of cancer diagnosis disclosure and patients’ coping self-efficacy. Also, the majority of cancer patients had moderate coping self-efficacy, which could be explained by the strong adherence and connectedness to Islamic faith, spiritual practices, and the social system that enforces patients’ abilities to use problem-focused coping, control their emotions, and stop unpleasant thoughts.

Recommendations

Further researches to assess patient’s coping self-efficacy in later or terminal stages for cancer diagnosis is recommended. Also, this study found that cancer patients lack different kind of support from the community. Thereby nurses should inform cancer patients with all the available resources they need.

Limitations

The study was limited to a small selected sample, one included facility, and difficulties during data collection.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to Dr. Elham Abdullah Al-Nagshabandi and Prof. Nahed Morsi for their contribution to this project and for their constructive recommendations, support and valuable guidance.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Coping Self-Efficacy Questionnaire

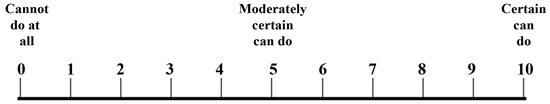

For each of the following items, write a number from 0 - 10, using the scale above.

When things aren’t going well for you, how confident are you that you can:

1) Keep from getting down in the dumps;

2) Talk positively to yourself;

3) Sort out what can be changed, and what can not be changed;

4) Get emotional support from friends and family;

5) Find solutions to your most difficult problems;

6) Break an upsetting problem down into smaller parts;

7) Leave options open when things get stressful;

8) Make a plan of action and follow it when confronted with a problem;

9) Develop new hobbies or recreations;

10) Take your mind off unpleasant thoughts;

11) Look for something good in a negative situation;

12) Keep from feeling sad;

13) See things from the other person’s point of view during a heated argument;

14) Try other solutions to your problems if your first solutions don’t work;

15) Stop yourself from being upset by unpleasant thoughts;

16) Make new friends;

17) Get friends to help you with the things you need;

18) Do something positive for yourself when you are feeling discouraged;

19) Make unpleasant thoughts go away;

20) Think about one part of the problem at a time;

21) Visualize a pleasant activity or place;

22) Keep yourself from feeling lonely;

23) Pray or meditate;

24) Get emotional support from community organizations or resources;

25) Stand your ground and fight for what you want;

26) Resist the impulse to act hastily when under pressure.

Credits to: Chesney, M.A., Neilands, T.B., Chambers, D.B., Taylor, J.M. and Folkman, S.A. (2006) Validity and Reliability Study of the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 421-437.