Technology and Investment

Vol.1 No.1(2010), Article ID:1329,10 pages DOI:10.4236/ti.2010.11006

On the Ideal Duration of Entrepreneurial Resources Commitment

Department of Economics, Division of Economic Development,

Athens National and Kapodistrian University, Athens, Greece

E-mail: ppetrak@econ.uoa.gr

Received November 20, 2009; revised December 7, 2009; accepted December 14, 2009

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Time Commitment, Payback Period

Abstract

The paper proposes that the entrepreneur’s perception of time in the form of average ideal duration of entrepreneurial resources commitment is an important personal trait. The entrepreneur develops a particular checking filter for the entrepreneurial involvement on which the evaluation of entrepreneurial opportunities is based. The concept of ideal time dimension of entrepreneurial engagement is crucially related to the development of structural prototype prevailing in space and time. Three main influences have been located with respect to the formation of duration on entrepreneurial commitment: microeconomic influences, long-term macro-environmental influences and short-term macro-environmental influences.

1. The Traditional Treatment of Preference in the Allocation of Investment Resources

The significance of preference of time in the bibliography, which is related to the allocation of resources and investment decisions generally, has been shown in at least three different approaches: the first refers to the rate of preference of time (RTP) of the neoclassical model [1, 2]; the second refers to the payback period criterion [3]; and the third to the concept of the intrinsic time of investors [4].

In the standard literature of project evaluation the payback criterion and hurdle rates criterion are often used. Lefley [3], in a review article on the PB method, states that the PB method is an important, popular, primary and traditional method [5] and is particularly used in advanced manufacturing technology projects [6]. Wambach [7] connects payback criterion and hurdle rates with the values of waiting. The hurdle rate is (usually) based on subjective assessments and the perceived level of project risk [3], particularly in cases in which future cash flows increase with time [8].

2. Perception of Time as a Cultural and Personal Entrepreneurial Trait

According to Bird [9] the entrepreneurship engagements in the resources-time interface have at least three time elements: perception, anticipation and action. Perception refers to people who are good judges of feasibility or the potential to instigate activity [10]. Anticipation denotes the future tense and touches on the possibilities of future states. It draws upon individuals’ abilities to recognise the future. Jaques [11] outlines two dimensions of time related to anticipation: succession and intuition. The latter captures the complexity of moving forward in time. The size and the value of the firm are fundamentally linked to the entrepreneur’s intentions.

According to Shane and Venkataraman [12] entrepreneurship means the process by which opportunities to create future goods and services are discovered, evaluated and exploited. In the framework of a well-structured theory for tracing and developing entrepreneurial opportunities [13] two levels of analysis appear. The first includes the process of tracing and developing entrepreneurial opportunities (development, recognition, perception, discovery and evaluation) while the second includes the factors that influence this process (entrepreneurial alertness, information asymmetry and prior knowledge, discovery versus purposeful search, social networks and finally personality traits).

The individual according to his sensitivity alertness [14, 15] reacts to the information he receives and recognises the entrepreneurial opportunity. The entrepreneurial opportunities are continuously evaluated either within a formal or informal process [16]. The individual informally collects information until it takes a more formal form and particularly when the collaboration of third parties is necessary in the search for essential resources. If the result of this process is satisfactory, then a feasibility study is produced.

The entrepreneur develops his entrepreneurial alertness either on the grounds of backward or forward interpretation [17] of incoming information and only to the level that he keeps pace with his time preference. For example, he excludes from his evaluation all information (in this case preference for short-term entrepreneurship) connected to long-term entrepreneurship. Thus entrepreneurial alertness is not a complete process but a unilaterally developed sensitivity which is biased in favour of short-terms actions. Note that in cases where a long-term perception of time prevails in society, then the long-term entrepreneurial trap can arise where no immediate results in entrepreneurial activity are taking place. Thus, the time preference is a personal attitude of the entire process of opportunity tracing and development.

The final phase of the evaluation by using time discount of future inflows constitutes only part of the influence of the time preference on the process of entrepreneurship. Time preference is much more important in all previous stages of the process of opportunity, identification and development.

3. The Macro-Environment and the Perception of Time

The macro-environment of entrepreneurship includes the economic and social dimensions. Central governments policies, local government aspects and financing systems [18] influence the general economic conditions of entrepreneurship [19]. The work ethic and cultural values shape the social background of the entrepreneurial environment [20].

Regarding the macroeconomic environment and its relation to the personal process of evaluation of time, we can trace a number of factors which seem to be able to shape it:

1) An entrepreneur who lives in a richer economic environment (per capita income), as compared to a poorer one, will obviously make a different evaluation. Under these circumstances, it is logical for the future to have a higher value since the present facilitates the resolution of most current personal and social problems.

2) Moreover, in an economy with higher rates of growth, for the same reasons the future is valued higher than the present [21]. The opposite is held in an economy with low rates of growth.

3) The entrepreneur is influenced by the phase of business cycle. If he is in the exodus of the recession phase he would prefer the future to the present, and the opposite in the upward phase.

4) The nominal interest rates combined with inflation rate indicate the evaluation of time, since they theoretically express the conditions of perfect competition and equilibrium markets.

5) A factor of similar importance emanates from the political environment and generally from the conditions of political stability. The entrepreneur who is active in an area with continuous political agitations and applications such as continuous changes in the administrative machine and in the tax system etc., will give with difficulty a higher value to the future over the present.

6) An entrepreneur who lives in an unstable economic environment will obviously show a higher preference for the present over the future. We may consider variability of income as a satisfactory proxy of instability of economic environment [22]. It is, therefore, logical to assume that he puts more weight on the present than on future periods.

7) Another factor that influences the evaluation of time is public finances conditions. A non-investment budgetary deficit of central government is in itself a powerful signal, ceteris paribus, for the entire society about the preference for the present versus the future.

8) The administrative burdens created by the operation of bureaucracy in terms of cost for the operation of firms are a serious factor that influences the process of evaluation of time [23], included the corruption cost that is probably more serious in the least developed economies. The higher this type of transactions cost, the higher the preference of present versus future is.

9) The legal framework of exploitation of entrepreneurial patents is one more factor which determinates the relationship between present and future. The non-existence of such a framework makes time disappears from the process of exploitation of an entrepreneurial idea [24]. The more its exploitation is developed for the short term, the less is the risk of losing the benefits from its exploitation.

10) The conditions of the job market considerably influence the time horizon of an entrepreneurial idea. When the job market is characterised by rigidity, the entrepreneur is led to abandon the flexibility that constitutes a basic element of entrepreneurship [18].

11) We should also give a great deal of attention to the more general geo-strategic factors of the entrepreneurial environment. Thus, an entrepreneur who is active in a region where national conflicts (wars, changes of borders, exterior threats) succeed one another, is being very logical in having a powerful preference for the present over the future.

4. Cultural Entrepreneurial Idiosyncrasies and the Perception of Time

The literature [23,25–27] shows a very clear picture of the level of research concerning the role of culture in the entrepreneurship.

1) The relation of individualism vs collectivism with entrepreneurs' perception of time is difficult to determine. We will stick to the idea that societies dominated by collectivist views have negative effects on the duration of entrepreneurial activities. This is because they usually do not promote the importance of individualist action.

2) Societies that show low uncertainty avoidance usually have high confidence in the future. Geletkanycz [28], raising a point of preference between a forward-looking vs more historical perspective, considers this perception to be a fifth cultural dimension, also known as Confucian Dynamism.

3) We could also accept that societies characterised by a high tolerance of social inequality (power distance) accept higher values for entrepreneurial activities. Also they accept a higher value for the future over the present since they usually promote perceptions of future expectations.

4) Societies which are characterised by masculinity (a materialist and achievement orientation) give more value to the future. Importance is given to maximising prosperity in the present life. Consequently if this requires certain sacrifices in the short-term present, it is quite bearable as long as it this is extended into a short number of future periods.

5. The Entrepreneur’s Personal Characteristics and the Specifics of the Project

Here we can specify two distinct sources which influence the entrepreneurial perception of time: personal characteristics and the microeconomics of the project. In the first category we should include: a) family situation; b) age; c) health; and d) educational level. Thus, marital status combined with personal characteristics may have mixed effects on the preference of present over the future. We may say that the higher the personal obligations, the higher the preference for the present. The same applies to the entrepreneur’s health condition. A good health creates conditions of preference for the future while the younger the entrepreneur is, the higher is the preference for the future. Finally, a high level of education encourages a preference for the future since it is related to human investments, which are originally accumulated on an expectations basis.

The microeconomics of the project include:

1) The nature and the origin of the resources that are to be used. The marginal value of obtaining each additional money unit depends on the way that it comes into the entrepreneur’s possession. The harder the way, the higher is its marginal value and consequently the higher is the preference for the present over the future.

2) A financial structure based on devotion to high own capital creates conditions of higher preference for the present.

3) The greater the size of the project, the greater the preference for the present. In contrast greater the size of the firm, the more confidence there will be in the future and consequently there will be greater preference for the future.

4) The sector in which the entrepreneur is working is very likely to influence his or her time preference. Entire sectors are characterised by ephemeral activities and entrepreneurs have a powerful preference for the present over the future.

6. Cognitive Factors, Entrepreneurial Motives and the Perception of Time

Following Locke [29] all entrepreneurial factors are the result of the combination or integration of cognition and motivation. The main cognitive factors are knowledge (industry, technology), skills (selling, bargaining, leadership, decision-making, planning etc.) and abilities (intelligence etc.) [30]. The possession of all the above factors develops vision. Vision may include opportunity fit, venture diagnostic and opportunity recognition. Entrepreneurial cognitions tend to be distinct from those of other business people, are universal and differ by national culture [27].

Do cognitions affect entrepreneurs’ perception of time? The answer that can be given in principle is positive even though it needs a lot more research to certify the degree of interaction. Thus it is obvious that when the businessman possesses good knowledge of the industry, he knows with precision the ideal horizon of his entrepreneurial activity. He also has a great perception of time which is formed about the specific industry in which he is operating as if is influenced by the precise business cycle phase and the life cycle of the product [31].

In any case we generally accept that the more developed cognitive factors are, the more easily the entrepreneur may be willing to extend the time horizon of his entrepreneurial effort and the more he will value the future over the present.

7. The Entrepreneurial Perception of Time: A Field Research

According to the analysis a Questionnaire was formed [32] with which we addressed 420 businessmen of SMEs in the Greek analysis whose own capital was smaller than 10,000,000 Euros (EU definition of SMEs) in the period 2002–2006. The size and sectoral structure of the firms in the sample were representative of the corresponding measures in the Greek economy. It is quite difficult to formulate questions that would concern all factors in the six different groups as we have located them. This would require a much broader and cross-cultural field research. However, very few factors were excluded.

We define duration as the time interval during which he should be dedicated to a precise entrepreneurial activity and not to any other. Then, in order to count the significance of the rest of the factors, we evaluate their influence on the change of this duration.

The size and sector of the firms chosen is distributed as follows: 20% of the firms are active in industry, 44% in trade and 36% in services. The respondents’ rate to the questionnaire was 32% to the total number of firms initially chosen. In 38% of the firms it became impossible to locate the entrepreneur; in 1% of cases the firms’ data were not correct, 1% of the firms were subsidiaries and the refusal rate was 28%. The research was conducted with personal interviews by a professional team.

From the answers to the questionnaire we estimate that the Average Ideal Duration of Entrepreneurial Commitment (AIDEC) is 5.57 years. The AIDEC is compared to Payback Period (PB) which is 3.91. The difference between AIDEC and ΡB criterion is statistically significant at a 95% level of significance. The finding of the difference in statistical significance leads us to the conclusion that the entrepreneur shapes an image for the time dimension of his involvement in the entrepreneurial effort which is larger than the requirement to take back his money but is not large enough to justify his involvement in investments that require long-term involvement. This finding is, up to a point, related to the fact that we refer to SMΕs that can not accurately be distinguished for the realisation of huge investments (with long-term depreciation).

Thus the entrepreneur gradually develops his entrepreneurial activity in a time horizon for each stage that varies around 5.57 years.

An important issue that arises is to what extent the AIDEC found, apart from picturing the time and geographical conditions under which the field research was conducted, is directly connected with the amount of investment referred to in the questionnaire (500,000EUR). Indeed, there is a question in the questionnaire that aims to reveal the relative elasticity that connects the project size and the AIDEC. So, if the project size is 2,000,000EUR then the AIDEC would be 6, 31 years. The difference found in the AIDEC is statistically important at a 95% level of significance. However, if the project size rises exorbitantly, the elasticity may become irrelevant.

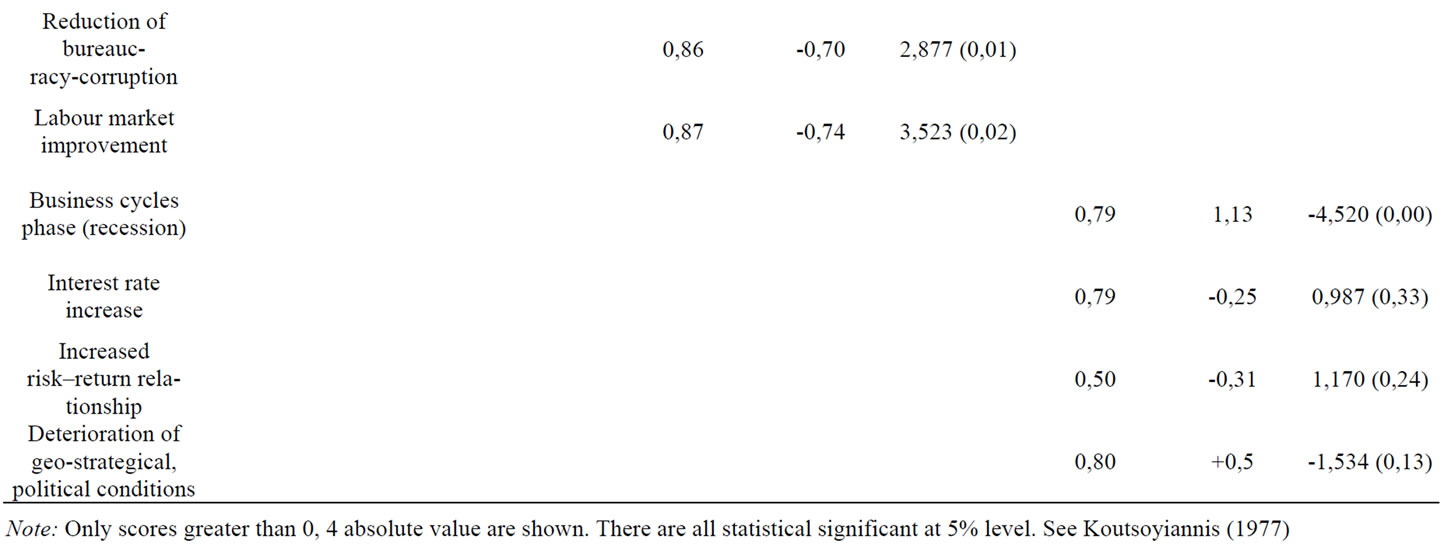

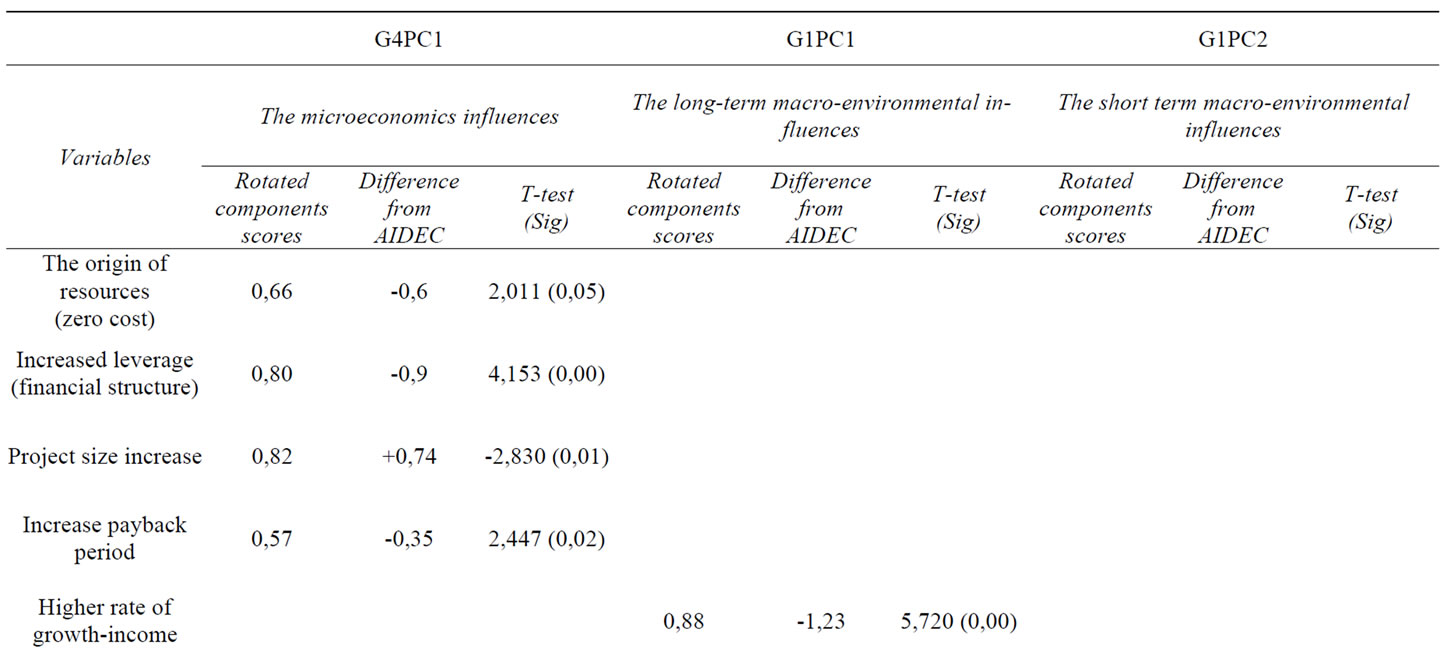

The answers to the questionnaire were categorized into six different groups (Categorization details are available upon request). The six groups are as follows: macroenvironmental variables (Group 1); cultural entrepreneurial idiosyncrasies (Group 2); personal characteristics (Group 3); microeconomics of the project (Group 4); entrepreneurial motives (Group 5); and cognitive variables (Group 6). Since between the variables multicollineanity is inherited and the amount of the data used is large, we employed factor analysis (with varimax rotation) on each group as a data reduction technique to reveal the main influences on the AIDEC. The analysis (Table 2) shows that the variables of Group 1 can be reduced to two principal components: G1PC1 and G1PC2 eingen values greater than one, accounting for the 68.6% of the variation in the macro-environmental variables. The variables of Group 2 can also be reduced to two principal components G2PC1 and G2PC2 which account for the 65.4% of the variation of the cultural and entrepreneurial variables. The variables of the Group 3 can be reduced to one G3PC1 which account for the 41.7% of the variation of the personal characteristics variables. The variables of Group 4 can be reduced to two, G4PC1 and G4PC2, which account for the project. Finally the variables of Group 5 can be reduced to three, GP5C1, G5PC2 and G5PC3 which account for 77% of the variation of the entrepreneurial motives variables. The principal components are uncorrelated.

Then we employee the Stepwise regression technique with the AIDEC as an independent variable and the GjPCi as independent variables. The model with the higher adjusted R square (37.3%) includes the G4PC1, the G1PC1 and G1PC2. (Table 1)

The three principal components exercise positive influences on the AIDEC. The first includes the origin of resources, the leverage influence, the project size influence and the payback period variable. The G2PC1 includes the rate of growth-income level, the bureaucracy, corruption influences and the labour market conditions. Some might characterise interest rate fluctuations, the level of risk-return them as the long term micro-environmental factor. The third includes the influence of business circles phase, relationship and finally the geo-strategical and political condition influences. This component could be characterised as the short-term macro-environmental factor.

An interesting point for discussion emerges from the exclusion of the member factors included in Groups 2 and 4 as explanatory variables of the AIDEC. It is case 4 of cultural entrepreneurial idiosyncrasies and entre

Table 1. Statistical significance of principle components on AIDEC.

Table 2. Principal components, variables’ scores and influences on the AIDEC.

preurenerial motives which have been found irrelevant to the AIDEC. So, perception of time emerges as a new independent entrepreneurial trait non-dependent either on the knowledge of cultural values or on the known entrepreneurial motives. On the contrary, it has a protogenic character that could influence the rest of the entreprenrial traits. This point may also give chance for further research.

An important issue that should also be investigated is connected to the extent that some factors have an effect on AIDEC. The positive factors (not all of them) function towards the decline of AIDEC. The negative factors function towards its increase. Thus, it seems that for the entrepreneur there is a notional time of entrepreneurial involvement that in any case would be better if it was smaller. The entrepreneur accepts for it to be lengthened only when he is forced to by external conditions. Thus, when he obtains part of his capital by a non-costing method (lottery or by state’s grants), the entrepreneur does not think that, in this case, he should have more patience to disengage from his entrepreneurial activity, but that the conditions have been created for his easier disengagement. The same happens when a) the financial leverage is increased; b) the payback period is increased; c) he lives in a wealthier economy; d) the costs of bureaucracy decline; and e) the conditions of the labour market improve. The opposite happens when the size of the project increases, if recession conditions prevail, and if conditions of political stability are getting worse.

There are two findings which require further comment, regarding the influence of the interest increase and the level of risk-return relationship. Here we revert to orthodox economic behaviour. This means that declining influences are exercised on the AIDEC on the basis of the following arguments: it seems that the entrepreneur has a notional time of entrepreneurial involvement that in any case would be better if it was smaller. But when the cost of money is increased or the time of systematic risk is increased, then his notional time of entrepreneurial involvement declines. Thus when the entrepreneur is forced by external conditions that concern the whole of the economy in which he is active, he compromises and accepts a longer AIDEC.

8. Conclusions

This paper has supported the idea that perception of time which concerns the average ideal duration of entrepreneurial commitment is an important personal trait. In other words, if the entrepreneur has formed a particular checking filter for the extent of the entrepreneurial involvement, he will never check on the possibility of being involved in larger scale entrepreneurial efforts. The new point proposed by this article at the theoretical level is that the rejection of these entrepreneurial activities is not performed according to a project appraisal criterion but is at an earlier level, which is at the beginning of the search and analysis of entrepreneurial opportunities.

Consequently, the perception of the AIDEC may be on a large scale responsible for the observed phenomenon of the reproduction of light production prototypes that are observed in specific geographical districts and for a long period of time.

The article proposes six factor groups that are responsible for the formation of AIDEC: macro-environmental factors, cultural entrepreneurial idiosyncrasies, personal characteristics, the microeconomics of the project, entrepreneurial motives and cognitive factors. Each group consists of a series of partial factors.

A research was conducted to locate the average ideal duration of entrepreneurial commitment. In this it was ascertained that an AIDEC of a specific duration (5.57 years) was specified according to the time and space characteristics of the field research conducted.

In this article it has been verified that the entrepreneur has a non-one-directional behaviour towards the formation of AIDEC and the factors that form it. Factors that have positive influence on entrepreneurial commitment, and allow entrepreneurs to disengage faster, function towards the reduction of AIDEC. In contrast, external factors that form a negative entrepreneurial environment force entrepreneurs to accept a longer AIDEC. The elasticities of AIDEC with its factors of influence are small. This non-one-directional behaviour could probably be connected with the cyclical and subjective perception of time through the states of the world in which the entrepreneur is engaged. The willing entrepreneur on the one hand conceives from past experiences that his disengagement may be delayed but will eventually come. On the other hand he recognises that the activation of certain factors may shorten the AIDEC for which he is happy.

What is shown from the above analysis is an ‘AIDEC trap’ for the economic policy that wishes to influence the production prototype towards the investments with a long average duration of entrepreneurial commitment.

In conclusion, we may argue that the analysis reveals that the average duration of entrepreneurial commitment is formed by long-lasting influences on entrepreneurial behaviour which enter with the form either of microeconomic variables or long-term or finally short-term macro-environmental influences.

9. References

[1] L. G. Epstein and S. E Zin, “Substitution, risk aversion, and the temporal behaviour of consumption and asset returns: an empirical analysis,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 99, pp. 269–286, 1991.

[2] P. Weil, “Nonexpected utility in macroeconomics,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 105, pp. 29–42, 1990.

[3] F. Lefley, “The payback method of investment appraisal: a review and synthesis,” International Journal Production Economics, Vol. 44, pp. 207–224, 1996.

[4] E. Derman, “The perception of time, risk and return during periods of speculation,” Quantitative Finance 2, pp. 282–296, 2002.

[5] D. S. Remer, S. B. Stokdyk and M. V. Driel, “Survey of project evaluation techniques currently used in industry,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 32, pp. 103–115, 1993.

[6] F. Lefley, “Capital investment appraisal of advanced manufacturing technology,” International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 32, No. 12, pp. 2751–2776, 1994.

[7] A. Wambach, “Payback criterion, hurdle rates and the gain of waiting,” International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 9, pp. 247–258, 2000.

[8] R. O. Chistiansen and C. Ferrell, “Survey of capital budgeting methods used by medium size manufacturing firms,” Baylor Business Studies, November and December, pp. 35–43, 1980.

[9] B. J. Bird and W. Page, “G. III. Time and entrepreneurship,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 5–136, 1997.

[10] P. Nutt and R. Backoff, “Crafting vision,” Journal of Management Inquiry, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 308–328, 1997.

[11] E. Jaques, “Introduction to special issue on time and entrepreneurship,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 11–12, 1997.

[12] S. Shane and S. Venkataraman, “The promise of entrepreneurship as a field or research,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 217–226, 2000.

[13] A. Ardichvili, R. Cardozo and S. Ray, “A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, No.1, pp. 105–123, 2003.

[14] I. M. Kirzner, “Competition and entrepreneurship.” Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

[15] I. M. Kirzner, “Perception, opportunity and profit.” Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

[16] J. A. Timmons, D. F. Muzyka, H. H. Stevenson, et al., “Opportunity recognition: the core of entrepreneurship,” N. C. Churchill et al., eds., Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley, MA: Babson College, pp. 109–123, 1987.

[17] T. Fu-Lai Yu, “Entrepreneurial alertness and discovery.” Review of Austrian Economics, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 47–63, 2001.

[18] Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Fostering Entrepreneurship: The OECD Jobs Strategy. OECD. 1998.

[19] S. Lee and S. Peterson, “Culture, entrepreneurial orientation, and global competitiveness.” Journal of World Business, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 401–416, 2000.

[20] D. C. McCleland, “the Achieving Society. Princeton,” NJ: Van Nostrand, 1961.

[21] P. D. Reynolds, D. Storey and P Westhead, “Regional characteristics affecting entrepreneurship: a cross-natio nal comparison,” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Wellesley, MA: Babson College, pp. 550–564, 1994.

[22] N. Majumder and D. Majumder, “Measuring income risk to promote macro markets,” Journal of Policy Modelling Vol. 24, pp. 607–619, 2002.

[23] C. Baughn and K. Neupert, “Culture and nation conditions facilitating entrepreneurial start ups,” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 1, pp. 313–330, 2003.

[24] Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Intellectual Property, Technology Transfer and Genetic Resources: An OECD Survey of Current Practices and Policies. OECD, 1996.

[25] G. Hofstede and M. H. Bond, “The Confucius connection: from cultural roots to economic growth,” Organization Dynamics Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 4–21, 2001.

[26] J. Hayton, G. Georg and S. Zahra, “National culture and entrepreneurship: a review of behavioural research,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 33–52, 2002.

[27] R. Mitchell, B. Smith, E. Morse, et al., “Are entrepreneurial cognitions universal? Assessing entrepreneurial cognitions across cultures,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 9–32, 2002.

[28] M. A. Geletkanycz, “The salience of culture’s consequences: the effects of cultural values on top executive commitment to the status quo,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, No. 8, pp. 615–634, 1997.

[29] E. A. Locke, “Motivation, cognition and action: an analysis of studies of task goals and knowledge,” Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 49, pp. 408–429, 2000.

[30] S. Shane, E. Locke and C. Collins, “Entrepreneurial motivation,” Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 257–279, 2003.

[31] R. Agarwall, “Survival of firms over the product life cycle.” Economic Journal, Vol. 63, No. 3, pp. 571–584, 1997.

[32] URL: http://elearn.elke.uoa.gr/petrakis/appendix/.

Appendix

Instructions for filling the questionnaire

1) We have chosen entrepreneurs from firms with equity up to 10,000,000EUR and established the year as being after 1980.

2) The enterprises are representative of the sectoral structure of enterprises active in the Greek economy.

3) The answers must be given by the entrepreneur or ‘the person in charge of the economical decisions’ of the enterprise.

4) The answers are based on the following assumption: the rest of the factors that could influence the answer, apart from those involved in the question, remain stable.

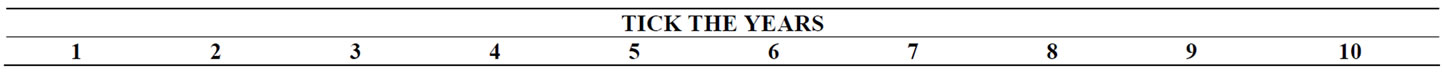

Question 1

Consider that you have already planned an investment of 500,000EUR in the field in which you are active or in any other field under the present circumstances. This investment is viable and profitable. For this investment any amount may be spent from your personal fund up to 500,000EUR. According to this investment you regain your fund in a specific period of time that you know today and which satisfies you. If you were to choose the ideal for your rate of return in a 1–10 years period of time, what would it be?

Please bear in mind that we define ‘duration’ as the period of time to which you are committed in any way, either by your personal work or by the commitment of your personal or external funds to a particular investment and to no other entrepreneurial activity.

Question 2

In a period of 1–10 years, when do you want to take back your money for this investment?

ONE ANSWER

Question 3

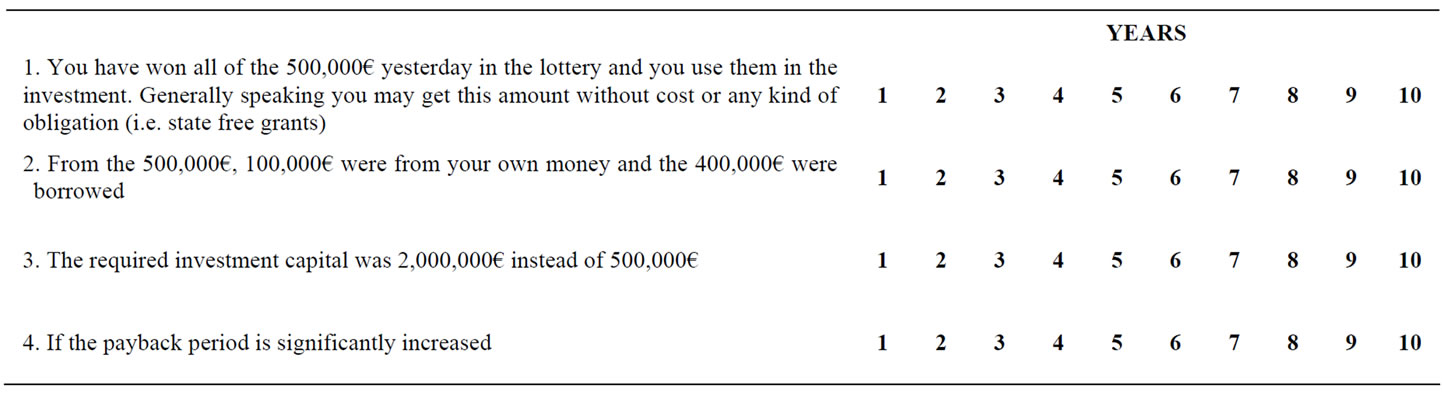

Now I would like you to tell me which would be the average ideal duration for this investment, in a 1–10 year period of time, if each of the following alternative conditions prevail?

Question 4

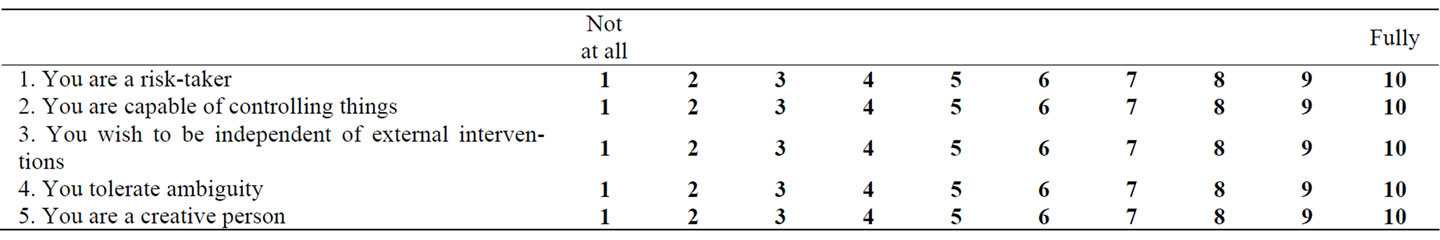

I will itemise various types of personal circumstances and I would like you to tell me about your relation to them. Please answer according to the scale from 1 to 10, where 1 signifies that this behaviour does not mean anything to you and 10 signifies that it means everything.

Question 5

I will itemise various types of personal circumstances and I would like you to tell me about your relation to them. Please answer according to the scale from 1 to 10, where 1 signifies that this behaviour does not mean anything to you and 10 signifies that it means everything.

Question 6

Now I would like you to tell me which would be the average ideal duration for this investment, in a 1–10 year period of time, if each of the following alternative conditions prevail?

DEMOGRAPHIC DATA