Modern Economy

Vol.4 No.1(2013), Article ID:27588,12 pages DOI:10.4236/me.2013.41005

A Discussion of the Suitability of Only One vs More than One Theory for Depicting Corporate Governance

1Faculty of Economics and Business, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), Kuching, Malaysia

2Institute for Postgraduate Studies, Multimedia University, Putra Jaya, Malaysia

Email: abdullahalmamun14@gmail.com

Received October 4, 2012; revised November 5, 2012; accepted December 7, 2012

Keywords: Corporate Governance; Agency Theory; Stakeholder Theory; Stewardship Theory and Institutional Theory

ABSTRACT

Agency theory predicts that the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the chairman positions should be held by different individuals in order to protect shareholder’s interest. Though there are mixed evidences on CEO duality and firm performance, most research have found that there is negative relationship between CEO duality and firm performance. Although, in the last decades of the twentieth century, agency theory became the dominant force in the theoretical understanding of corporate governance, it does not however cover all aspects of corporate governance. This paper aims to explore whether it is better to combine various theories in order to describe effective and good corporate governance or theorizing corporate governance based on one theory only. This will cover corporate governance theories which include agency theory, stakeholder theory, stewardship theory, and institutional theory.

1. Introduction

Modern business environment is changing in haste and it is forcing management and organizations to develop ethical responsibility, modern and profitable businesses. In recent decades, corporations have been found as leading and powerful institution. Corporations didn’t limit their existence just within the developed nations rather they extended their reach to around the world depending on their size and capabilities. Existence of such powerful and leading organisations influences in various aspects such as the economies and socio cultural landscape of country. Due to various corporate scandals around the world including Enron, WorldCom, Marconi and Royal Ahold (Mir and Seboui, [1]) has shaken the trust of shareholders. Shareholders’ value is significantly affected due to these scandals. Besides this emergence of technological era has accelerated the globalisation, which decline the governmental control. All these situations gave a wakeup call for greater accountability which is one of the mechanisms of corporate governance (Abdullah and Valentine, [2]).

Therefore corporate governance has been recognised as significant element in managing corporations in modern global phenomenon. Corporate governance includes quite number theories. Therefore, this paper aims to investigate whether it is better to combine more than agency theory in order to present a comprehensive theoretical overview of good corporate governance or corporate governance based on one theory only. In this vein theories going to be covered in this study include agency theory, stakeholder theory, stewardship theory and institutional theory.

2. Agency Theory

2.1. Origin of Agency Theory

Organisational theories have been developed by modern researchers with the driving force from Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations”. Adam Smith deduced that, when a firm is controlled by a number of people or a group of individuals rather than the owner of the firm, principal’s (shareholder or owner) objectives are highly likely to be diluted rather than ideally achieved. Based on Adam Smith’s assumption regarding the ownership and control separation in large firms, Berle and Means [3] argued that as long as ownership gets increasingly held by people other than owners, the industry becomes consolidated and hence the checks to limit the use of power tend to disappear (McCrew, [4]).

However, in 1976 Jensen and Meckling [5] came up with the concern of ownership-control separation into a fully fledged agency problem which is comprised within the economic theory of the firm, where costs’ of agency problem has been identified and who bears that costs.

2.2. Definition of Agency Theory

Agency theory is based on the problems related to separation of ownership and controllability. Jensen and Meckling [5] defined the agency problem as problem that arises when one party (Principals) makes contract with another party (Agents) aiming to make decisions on behalf of the principals. Jensen and Meckling [5] further argued that when the management interest is low, there is a greater likelihood that the management involves itself in value decreasing activities. An agency problem occurs as agents tend to hide information from the principals and take actions in order to achieve their own interest (Enron, WorldCom, Marconi and Royal Ahold).

An agency problem comes into play when the CEO sets some goals which contradict of those shareholders. This problem occurs when the CEO has little or no interest in the outcome of his decisions (Jensen and Meckling, [5]; Fama and Jensen, [6]). Boyd [7] asserts that the CEO is likely to implement such a strategy that will maximise his or her personal interest at the expense of shareholders’ while at little or no risk to him or her.

Craig [8] deduced that agency relationship refers to many relationships involved in the delegation of decision making from one party (Principal) to another party (Agent). This definition considers that shareholding persuades delegation of managerial responsibility from firm’s principals to their upper ranked agents. Delegation and various risks cause a moral hazard to the executives. Jensen [9] asserts that such moral hazard to executives gives opportunity to seek for additional compensation through opportunistic means such as perquisites, shirking and free-riding and at the same time the principals are motivated to increase their monitoring fees and incentives.

Jensen and Meckling [5] defined the agency costs as the inevitable loss of firm value that arises with the agency problems along with the costs of contractual monitoring and bonding. Watts and Zimmerman [10] developed Positive Accounting theory which focuses on the relationship between various individuals involved in providing resources to an organisation. This could be the relationship between the owners (as suppliers of equity capital) and the managers (as suppliers of managerial labour). PAT assumes that self interest is driven by individual actions. Or in other words, principal and agent are fully wary in maximizing their own wealth. It is assumed that agency theory believes that the agents (management) are not always likely to act in the best interest of the owners (principals). Such assumption requires the principals to consider appropriate incentives or bonus scheme for the agent and at the same time set up proper monitoring mechanism so that any unusual activities can be controlled. Three types of costs have been identified by Jensen and Meckling [5] due to agency problem, namely:

• Monitoring costs

• Bonding costs

• Residual loss

2.3. Monitoring Costs

Craig [8] argues that assuming managers (agents) will be responsible for preparing the financial statements, there will be attempt to overstate profits thereby increasing the ultimate share of incentives or bonus as their (agent) actions are self interest driven. On the other hand Jensen and Meckling [5] deduce that principal and agent are concerned in maximizing their own interest or wealth, while agents (decision makers) may not take actions in the best interest of the owners (principals). Therefore both Jensen and Meckling [5] and Craig [8] presume that the principal has to monitor the agents by setting up monitoring mechanisms which could be in the form of hiring external auditors who will audit the financial reports. The cost of undertaking an audit is referred to as monitoring costs. In fact Jensen and Meckling [5] argued that monitoring is a comprehensive term as it contains controls and does not merely observe and measure manager’s performance but rather sets budget restrictions and operating rules.

2.4. Bonding Costs

As agents are concerned on maximizing their own wealth, a mechanism can be established that will align the interest of the managers (agent) of the firm with those of the owners (shareholder) (Henderson et al. [11]). Mechanisms of aligning interest may include providing the manager with profit share of the firm based on accounting outcome or performance. Such accounting based alignment highly requires producing financial statements (Craig, [8]). Managers are required to bond themselves to prepare these financial statements which are costly and referred to as bonding cost. However, Jensen and Meckling [5] argued that agents may take action by spending resources in assuring that it would not take actions which would not have negative effect on the principal, which is considered as bonding costs. For instance, bond provided by the agent.

2.5. Residual Loss

However, though the monitoring and bonding costs are incurred, there may still be lose to the principals provided that the agents make decisions that are different from those that could maximize principals’ interest (Williamson, [12]). This lose is recognised as residual loss. In general, monitoring and bonding costs are incurred in order to minimize or reduce the agency problem. However, unlike the assumption of self interest that individuals take that aim to benefit the principal there will be no need to take such initiatives. Craig [8] argues that not all the actions of agents can be controlled by monitoring or contractual arrangements or otherwise, there will always be some residual costs associated with appointing agents. Williamson [12] argues that principals might seek to minimize residual cost, since it is considered as key cost.

In addition dilution is very common in corporations. When owner of a firm sells a portion of the equity firm’s to others, dilution of ownership occurs and this situation separates the ownership and control. Dilution can happen for various reasons, for instance to attain better efficacy by distributing some portions of ownership rights. Usually the old principal holds with the controlling power rather than the new principal. In this vein, the old princepal operates the firm as agent aiming to protect new principals’ interest.

In this situation new principal may feel that the decision made by the older owner or agent requires to be monitored, in expectation of divergence of interests. Here, the new principal may tend to deduct likely monitoring costs from the price payable to the old principal for buying shares. Such a payment strategy decreases old principal’s wealth. Moreover, old principal (agent) may require making bond in order to provide assurance to the new principal. And bonding cost will be borne by the old principal. In order to ensure that the agency costs are at the minimum level, old principal bears all the costs from the separation of ownership and control.

In some circumstances, owners of the firm may decide to dispense with the entire ownership. Jensen and Meckling [5] deduce that the degree to which owner may dispense or dilute the ownership status is based on factors which could include sum of monitoring and bonding costs allied to the separation of ownership and control in relation to controlling wholly owned over partially owned resources.

There are mixed evidence in respect of this prediction of agency theory. The board member responsible for the executive management is called the managing director or chief executive officer. When chairman is also performing the role of CEO, that refers to CEO duality. CEO is responsible for the running of board as well as operating the firm. Such duality is found in a number of countries such as Australia, and the United States. Donalson and Davis [13] argue that a small portion of firms in Australia have CEO duality, while 80 percent of companies in the United States have CEOs who also hold the position of chairman (Kesner and Dalton, [14]). Various studies found that in combining of these two roles individual become so much powerful, as it ought not to be (Ahmed, [15]; Davis, [16]; Rechner and Dalton, [17]). However, subsequently the dual leadership has dropped from 80 percent to 60 percent by 2003, which is shown in the Table 1 below.

When CEO also holds the position of board chair, the role of the board as monitoring and control mechanism is compromised. According to the agency theory while the CEO is also the board chair, it weakens board monitoring and control and in this situation it is likely that shareholders’ interests will be sacrificed at a degree in favour of management. Their opportunistic activities could result in higher levels of executive compensation (Levy, [19]; Dayton, [20]).

Consequently, an agency problem exists when the CEO has established goals that are at variance with those of shareholders. Such problem is more likely to occur when the CEO has little or no financial interest in the outcome of his decisions (Jensen and Meckling, [5]; Fama and Jensen, [6]).

2.6. Views on Agency Theory

There are several findings which validate agency theory from different contexts. These Studies include Denis and Serin, [21]; Kehoe, [22]; Krishnan and Loch, [23] who pursued their research on public offer of new capital or initial public offering (IPO), set up of franchisee and labour union transactions respectively.

Denis and Serin [21] in particular, argue that managers in firm incorporate diversifications because their private benefits related with diversified portfolio (pecuniary which is incentives and non-pecuniary such as power, Jensen and Meckling, [5]). This suggests that diversification can lead to value reduction as firm trades at a discount as against their single segment peers. Franchisee set up is efficient in mitigating agency problems (Kehoe, [22]). This is because franchisee compensates from the residual claims of their individual units. Hence, they bear the cost proportionately based on the units owned. On the other hand, Jensen and Meckling [5] argue that in the context of Anglo-American corporate governance system is an agency relationship that agents will not act to maximise the returns of principals unless corporate governance mechanisms are set to minimize the divergence of

Table 1. Dual leadership in USA.

Source: Chia et al. [18].

interests between shareholders and managers or in other words principal and agents.

Finally it can be posited that agency theory is a significant proposition in firm discipline. The theory assumes that when ownership and control is separated in a firm, the CEO, and manager act as agent on behalf of the principal (makes decisions) tends to bringing moral hazards by seizing wealth which happens at the expense of owner. Therefore, it is suggested that the owner set up corporate governance mechanisms that will deter the CEO, managers (agent) from such behaviour. Mechanisms could be various incentive plans including share issue, options and share of profit. These incentives are either monitoring by principal or bonding by agent. In Figure 1, agency theory mentioned in the following figure.

2.7. Corporate Governance Responses to Agency Problem

Jensen and Meckling [5] found that the important role of monitoring in agency relationships that authority does not scan further the way how large firms attain efficient monitoring or the way firms construct corporate governance aiming to control the agency costs created due to the separation of control and ownership. However, efficient control of agency problem in large firms is pursued by establishment of internal devices in response to competitor firms or competition from other firms (Fama, [25]). Fama [5] further argues that individual managers within the firm are controlled by the discipline of market and opportunities for their services both within and outside the firm.

Fama and Jensen [6] argue that firms segregate decision making process and decision control both at top level and lower level of the firm hierarchy, where top level refers to the board and managers and lower level refers to the managers and workers. Here, decision management is explained as carrying out a firm’s function and decision control is explained as overseeing the performance of the decision management function.

Fama and Jensen [6] argue that the reason behind contrasting decision management and decision control is to avoid situations where agent without ownership of firm may intend to maximize own wealth by decisions which may not be for the best interest of the principal. Board of directors are appointed by the principals as response of corporate governance to minimize or control the agency problem which arises with senior managers including the CEO. Board of directors have the authority of decision control whilst authority of decision management rights is vested in the senior managers. Ahmed [15] suggests that shareholder and CEO relationship will inevitably become problematic as managerial actions depart from those required by shareholders to maximise their own interest and shareholders seek to prevent CEO from maximising their wealth. In this vein, corporate governance is concerned with the constraints that are applied to minimise the opportunistic activities of the CEO, hence, reduce the agency problem.

In a similar vein, management control system is also designed with the expectation that managers oversee the tasks carried out by the lower level managers and workers. Stettler [26] argues that the operational and accounting duties be separated. There is no conflict of interest as the resources held by the principal in such situation resulted from the segregation of decision management and decision control, while decision maker is also the principal.

3. Stakeholder Theory

In recent years, the concept of stakeholder has achieved widespread popularity among academics, the media and corporate managers. Now the question that rises is: what is stakeholder theory? There are different definitions given

Lubatkin et al. [24].

Figure 1. Agency theory’s view of principal agent relationship.

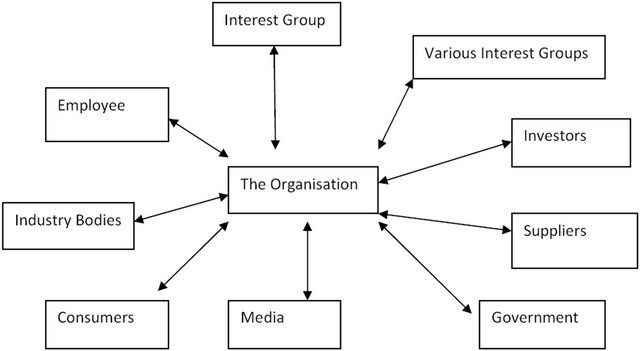

on stakeholder theory by different scholars. Stanford Research Institute (SRI) defined stakeholder theory in 1963 as “those groups without whose support the organisation would cease to exist”. This definition was modified by Freeman [27] who defined stakeholder theory as those groups who are vital to the survival and success of the organisation. It is obvious that the definition given is organisation oriented. However, in earlier researcher stakeholder was defined as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organisation objectives” (Freeman, [28]). Friedman [29] however argued that the definition given by Freeman [28] is more balanced and takes wider area than the definition given by SRI (1963) this is because it includes individuals outside the firm and that groups may consider themselves to be stakeholders of an organisation without the firm considering them to be such. In addition, Gray, Owen and Adams [30] stated that stakeholders are identified by the organisation of concern, by reference to the extent to which the organisation believes the interplay with each group needs to be managed in order to further the interests of the organisation. Conventionally, interest of the organisation is nothing but profit seeking assumption. In Freeman’s definitional perspective, the organisation is seen as part of a larger social system. Stakeholders would include shareholders, employees, customers, lenders, suppliers, local charities, various interest groups and governments.

Similarly, in Figure 2, Craig [8] asserted that the view of stakeholder theory is that all the stakeholders have right to be provided with information about how the organisation is affecting them (perhaps through pollution, community sponsorship, provision of employment, safety initiatives, etc.), even if they choose not to use the information and even if they cannot directly affect the survival of the organisation. Figure 1 depicts the inter relationship between various stakeholders. Such practice will increase the transparency of organisational activities and performance. Therefore, it can be said that stakeholder theory can assist firms to achieve one of the corporate governance mechanisms, which is transparency, while according to the Gray, Owen and Adams [30] practicing stakeholder theory helps organisation to achieve the organisational goals which include increasing profitability.

Ullmann [31] argues that the greater the importance to the organisation of the stakeholder’s resources/support, the greater the probability that a particular stakeholder’s expectations will be accommodated within the organisation’s operations. This perspective includes various activities such as public reporting. Moreover, organisations will have an incentive to disclose information about their various programs and initiatives to the stakeholder groups concerned to clearly indicate that they are conforming to those stakeholders’ expectations, as organisations must necessarily balance the expectations of various stakeholder groups.

Within the same line of thought, Roberts (p. 598) [32] argued that stakeholder related activities are useful in developing and maintaining satisfactory relationships with stockholders, creditors and other related parties. Developing a corporate reputation through performing and disclosing necessary reports activities is part of a strategy for managing stakeholder relationships. Disclosing necessary reporting to the shareholders is the duty of management and proper disclosure can build good relationship between owners and managers while at the same time reducing agency problem. However, stakeholder theory does not directly provide prescriptions about what information should be disclosed (Craig, [8]) other than indicating that the provision of information, including information within an annual report can, if thoughtfully considered, be useful for the continued operations of a business entity.

Quite a number of companies have developed and run

Source: Craig [8].

Figure 2. Stakeholder theory.

their business in terms highly consistent with stakeholder theory. These firms include JandJ, eBay, Google, Lincoln Electric, AES featured in Built to last and Good to Great (Collins, [33]; Collins and Porras, [34]) continued to provide compelling examples of how managers understand the core insights of stakeholder theory and use them to create outstanding business. Freeman et al. [35] asserted that the concept of stakeholder theory can vary from individuals to individuals, as it does not follow that we should cast it as everything non-shareholder oriented. Here it is significant to remember that shareholders are one of the stakeholders. Freeman [27] argues that segregating shareholder for instance from stakeholder concept is nothing but contrasting apples with fruit. Shareholders are one of the stakeholders and it does not get us anywhere to try to contrast the two. Therefore, stakeholder theory can help firms to achieve organisational goals resulting from satisfying shareholders. Freeman et al. [27] further argued that stakeholder theory gives managers more resources and a greater capability to deal with companies’ internal problem.

Freeman et al. [27] concluded that creating value for stakeholders creates value for shareholders. In supporting stakeholder view, Etzioni [36] concludes that the moral legitimacy of the claim that shareholders have certain rights and entitlements as shareholders sink their capital, but Etzioni [36] maintains that “the same basic claim should be extended to all those who invest in the corporation”. This includes: employees (especially those who worked for a corporation for many years and loyally); the community (to the extent special investments are made that specifically benefit that corporation); creditors (especially large, long-term ones); and, under some conditions, clients.

However Goodpaster [37] criticises that a multi-fiduciary stakeholder approach has failed to recognize that the relationship between management and stockholders is ethically different in kind from the relationship between management and other parties (like employees, suppliers, customers, etc.). Goodpaster [37] further argues that though managers have many non-fiduciary duties to various stakeholder groups, their fiduciary duties are only to shareholders.

4. Stewardship Theory

According to scholars, though agency theory has its origin in economics, stewardship theory has evolved from psychology and sociology. Stewardship theory grew out of the seminal work by Donaldson and Davis [38] and was developed as a model where senior executives act as stewards for the organization and in the best interests of the principals. The model given by Donaldson and Davis [38] asserts that managers will make decisions and act in the best interest of the firm, putting collectivist options above self-serving options. Notably, stewards are motivated only by making the right decisions which are in the best interest of the organisation, as there is strong assumption that stewards will benefit, if the firm is prospered. At the same time, stewardship theory presumes that executives and managers’ main duty is maximizing firm performance, while working under the premise as so; both principal and stewards can be benefited from the performance of the organisation.

Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson [39] defined stewardship theory as “a steward protects and maximises shareholders wealth through firm performance, because by doing so, the steward’s utility functions are maximized”. In this definition, the writers identified firm executives and managers as the stewards working for the principal. Later, Block [40] suggested the stewardship role as “service over self-interest” believing that both organizational and individual needs will be achieved at the best by honouring relationships and treating followers like “owners and partners”. In extension of stewardship theory definition, Caldwell and Karri [41] posited that there are covenantal duties owed to all stakeholders that acknowledged the importance of a systemic fit of organization governance with the conditions of its environment. However, stewardship can simply be defined as a behaviour that places the long term interest of the organisation as well as the shareholders a head of individuals’ self-interest. Company executives and managers are aimed to protect and make profits for the principals (shareholders), while in agency theory, firm executives and managers aim to work for their self interest. On the other hand, Donaldson and Daivis, [38] argued that stewardship theory ignores individualism, rather firm executives and managers play their role as stewards by aligning their interest along with the organisation goals. According to the Figure 3, in fact, stewardship concept suggests that successful organisation leads to happiness and hence motivate stewards, not individual success or goals attained (Abdullah and Valentine, [2]).

Unlike agency theory, the principal espouses stewardship theory which empowers managers and executives with the information and the equipment and the power believing that they will make decisions in the best interest of the organisation and for the principals. It enables the decision makers to act on behalf of the firm and for the firm, having faith that they will maximise the long term return of the firm. Argyris [42] noted that placing control structure or monitoring on executives or managers ultimately discourages them and will result in unproductive outcomes for the organisation as well as principals and stewards. Stewardship theory believes in acting in the best interest of the organisation, unlike agency theory, therefore it argues that any control or monitoring

Source: Abdullah and Valentine [2].

Figure 3. Stewardship theory model.

structure may de-motivate decision makers, which may have negative impact on firm performance.

However, in order not to place the full authority to the stewards without any control and monitoring structures, principals are required to get rid of the typical assumptions which are the result of agency theory. Principals are required to build the requisite trusting relationship with executives and managers. Placing the authority can help the stewards to make decisions independently for best interest of the organisation. Though agency theory talks about focusing on controlling cost and minimizing downside, stewardship theory focuses on maximizing the upside of the relationship (Donaldson and Davis, [38]).

While working on high-commitment organisations, Walton [43] found there is consistency between the dimensions of open communications and empowerment. Later the same findings empirically tested by Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson [39] where research found a series of factors which describe the management philosophy of stewardship, those series of factors include trust, open communication, empowerment, long-term orientation and performance enhancement. Stewardship theory is the combination of all these factors. Trust dimension is significant in building relationships between stewards and principals, so that principals can place the authority to executives and managers to get the works done in the best interest of organisations.

However, as decision makers, executives and managers have to maintain their reputation to lead the firm in such a way that it maximizes the profitability resulting in maximum returns to the principals invested capital (Daily et. al. [44]). Here individual performance is impacted by the firm’s performance. Therefore, executives and managers are managing and working for the firms having intention to be seen as effective stewards in the organisation (Fama, [5]). For example, Abdullah and Valentine [2] argued that stewardship model can be better linked to Japan, as employees in Japan take the role of stewards and ownership diligently. On the other hand, Shleifer and Vishny [45] proposed that managers and executives return finance to investors to establish a good reputation so that that they can re-enter the market for future finance.

From stewardship theory perspective unifying the CEO and chairman role is effective as this can reduce agency costs resulting in a great role of stewards in the organisation. Abdullah and Valentine [2] suggested that such stewardship can help to safeguard the interest of the principals (shareholders). Donaldson and Davis [2] proposed that combining both theories can bring improvements in the returns in organisations than when separated and this was empirically tested. Furthermore, stewardship theory identifies the significance of structures that empower firm executives and directors who are offered maximum autonomy to build on trust (Donaldson and Davis, [38]). It emphasises for managers and directors to act more as an individual to maximize the firm’s profitability resulting in the maximization of shareholder’s return on invested capital. Wealth creation is a variable sum opportunity that is synergistic and practical. Hosmer [46] argued that the manager’s role is to maximize the potential of the organization to pursue long-term wealth creation with organizational and individual goals best achieved by pursuing collective ends. Peggy and Hugh [47] argued that unlike agency theory, stewardship theory helps in aligning the goals of managers and shareholders. When managers and shareholders’ goals are aligned, firm performance is expected to increase as there is no conflict of self-interest.

5. Institutional Theory

Coase [48] proposed that institutions were created by human beings to decrease the uncertainties of transactions between economic agents, where a major part of those uncertainties are due to opportunistic human behaviour (Williamson, [49]). Williamson [49] further argued that without institutions and markets firms may have never existed and transactions could have never begun. Traditional definition of institutions are found as what we regard or do not regard as acceptable and thus determine the framework in which any action finds its legitimacy. Suchman [50] argued that an organisation cannot survive without legitimacy: an approval of its general environment that its actions are desirable, suitable and are adapted, with the interior of the standards, values and beliefs system, socially built. Later in 2005, Krishna and Das [51] made similar conclusion, where they posited that, institutional perspective assumes that the environment recognises and empowers institutions to award firms, or withhold from firms, resources such as legitimacy. The tenets of institutional theory are also best met in a business environment with high level of regulation.

Institutional theory argues that organisations are not just a place where goods and services are produced rather these are also social and cultural systems. In other words, firms not only engage themselves in competition but legitimised themselves also. A major paper in the development of institutional theory was by DiMaggio and Powell [52] who defined an institutional field as those organisations that in the aggregate, constitute a recognised area of institutional life: key suppliers, resources, regulatory agencies, and other organisations that produce similar products and services.

DiMaggio and Powell [52] viewed the process by which organisations tend to adopt the same structures and practice “isomorphism”. Isomorphism is a process that causes one unit in a population to resemble other units in the population that face the same set of environmental conditions. DiMaggio and Powell [52] found three different isomorphism processes namely coercive, mimetic and normative isomorphism.

Coercive isomorphism arises when organisations change their institutional practices in response to pressure from stakeholders upon whom the organisation is dependent. Company is coerced into adapting its existing voluntary corporate reporting practices, where stakeholders are taken into consideration. Once the voluntary corporate reporting is adopted, stakeholders are pleased with the organisation. Such practice will help the organisation to be competitive on the market resulting positive firm performance.

Institutional theory pressures to meet certain standards of corporate governance (Shleifer and Vishny, [45]), which is linked to firm performance. Krishna and Das [51] argued that institutional perspectives on corporate governance are best met in an environment with high levels of regulatory efficiency. This finding is similar to Kathleen [53] where it mentioned that organisations are the way they are for no other reason than that the way they are is the legitimate way to organise. The key concept of this idea is that organisational actions evolve over time and become legitimated within an organisation and an environment.

Seal [54] asserted that the significance of institution theory is the openness about human behaviour and organisational practices. This theory also offers the way, how to link the institutionally informed management accounting research that has been increasingly adopted at the organisational level to the wider political, legal and social processes associated with corporate governance and professionalization.

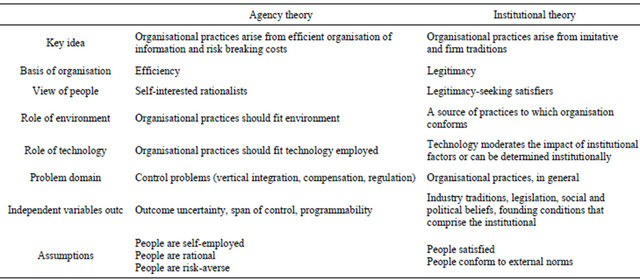

Kathleen [53] made a comparison between agency theory and institutional theory depicted in Table 2 below.

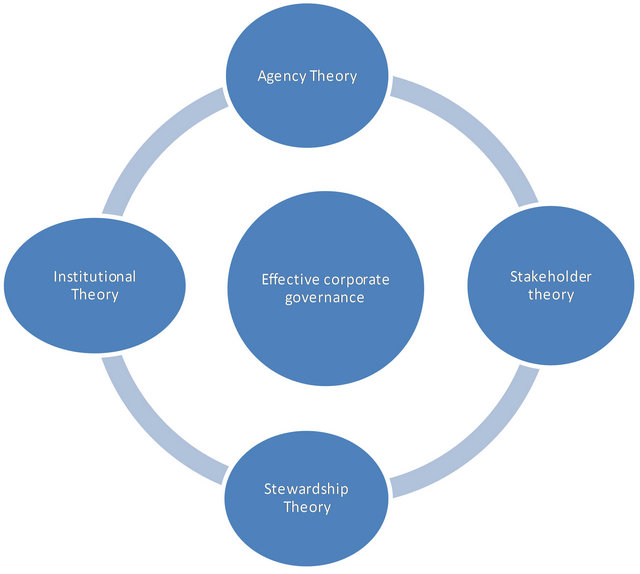

In this business sustainability journal we have discover the reality of different approach that exists in effective corporate governing. No one theory can give us the best performance result but a combination of all can deliver the business need and keep the organization running while balancing the principal and the manager rights over the business. In Figure 4, we have seen how this has over lapping effect on the other three theories, Like, the institutional theory states that firms not only engage themselves in competition but legitimised themselves. On the other hand, Stewardship theory is defined as “stewards protect and maximise shareholders wealth through firm performance. By doing so, the steward’s utility functions are maximized”. Hence the link is clear how institutional theory is a subset of stewardship theory.

Agency theory is based on the problems related to separation of ownership and controllability. In Freeman’s definitional perspective, the organisation is seen as part of a larger social system. Stakeholders would include shareholders, employees, customers, lenders, suppliers, local charities, various interest groups and governments. So we can see how various stakeholders if left to make decision alone can open up sever loophole in principal wealth protection. Therefore, in order to strengthen corporation effectiveness we need to emphasise in all of them. As agency theory dictate that the greater likelihood that the management involves itself in value decreasing activities. An agency problem occurs as agents tend to hide information from the principals and take actions in order to achieve their own interest (Enron, WorldCom, Marconi and Royal Ahold). With the above theory we can see how stakeholder theory proves agency theory about each component of an organization take action

Table 2. Comparison between agency theory and institutional theory.

Figure 4. Analyse the theories.

according to their own benefit.

Now if we look at the Institutional theory and agency theory, these two theories have distinct differences. One emphasises on the Management ethics and the other talks about the formation of social culture of organization life. As the organization continues to exist, it also develops a unique personality in which agency theory comes in and ultimately the principal might lose control and proving agency theory.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Though there are a number of theories related to corporate governance, the evolution of agency theory, stakeholder theory, stewardship theory and institutional theory explain the CEO/chairman duality, audit committee and the role of management most. These four theories are considered as the fundamental theories of corporate governance. In considering the stakeholder theory and institutional theory, it can be deduced that corporate governance is more towards social relationships rather than structure. All the four theories discussed above mostly on the perception that principals get return on their investment in the firm. The various models of corporate governance that exist globally have evolved as economies and the corporate structure were shaped, simply following convention, or based on environmental influences such as worldview, culture, and the legislative and political framework. Due to abrupt changes in external and internal business environment, corporate governance also changes constantly. External environmental factors include business collaborations, financial funding, new business venture, technological advancements, mergers and acquisitions, while internal environmental factors include shareholders, stakeholders and profit maximization of the firm. All these environmental factors result in changes directly or indirectly to corporate governance. Corporate governance mechanisms may differ from country to country based on economic positions, political and cultural situations.

Hofstede and Hofstede [55] argued that the relevance and applicability of theories vary between developed and developing market. As the institutional and organisational framework is weak in the developing market, it can be posited that agency theory more likely to be applied in depicting the organisational behaviour and business management principles in developed market. It is contended, from agency theory perspective, that the delegation of executive and managerial responsibilities by principles to agents demands the presence of mechanisms that tends to align the interest of corporate population or ensures that agents (executives and managers) exercise their authority in order to generate the uppermost return for the owners. Purpose of this study was to explore theories of corporate governance in a broad range which would cover all the aspects of corporate governance rather than a partial context (which is principles and agents relationship covered by agency theory). Freeman et al. [27] argued that stakeholder theory better equips managers to articulate and foster the shared purpose of their firm. This theory acknowledges a wide range of answers rather than only principles and agents. Stakeholder theory posits that firm is not only to generate profit for the shareholders but to defend an image and values respecting all shareholders.

As mentioned earlier that agency theory does not cover corporate governance fully, combining the agency, stakeholder, stewardship and institutional theories disclose the differing authorities of different types of shareholders within the developing market firms. These theories largely, point out that there is a positive reinforcing effect on firm performance. In reality, contributions of different theories at corporate governance level establish a foundation which redefines the various stakes of the firm and the model of corporate governance.

In addition, this paper suggests that effective corporate governance could not be illustrated by one theory rather it needs a combination of more than one. Therefore, agency theory can cover the management and principals, while stakeholder theory can address the social relationships and institutional theory can cover the rules and regulations and enforcement of those.

REFERENCES

- A. E. Mir and S. Seboui, “Corporate Governance and the Relationship between EVA and Created Shareholder Value,” Corporate Governance, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2008, pp. 46- 58. doi:10.1108/14720700810853392

- H. Abdullah and B. Valentine, “Fundamental and Ethics Theories of Corporate Governance,” Middle Eastern Finance and Economics, No. 4, 2009, pp. 88-96.

- A. Berle and G. Means, “The Modern Corporation and Private Property,” MacMillan, New York, 1932.

- T. K. McCraw, “In Retrospect: Berle and Means,” Reviews in American History, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1990, pp. 578-596. doi:10.2307/2703058

- M. C. Jensen, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1976, pp. 305-360.

- E. F. Fama and M. C. Jensen, “Separation of Ownership and Control,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1983, pp. 301-325. doi:10.1086/467037

- B. Boyd, “CEO Duality and Firm Performance: A Contingency Model,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4, 1995, pp. 301-312. doi:10.1002/smj.4250160404

- D. Craig, “Australian Financial Accounting,” 6th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2010.

- M. C. Jensen, “The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, and the Failure of Internal Control Systems,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 48, No. 3, 1993, pp. 831-880. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1993.tb04022.x

- R. L. Watts and J. L. Zimmerman, “Towards a Positive of the Theory Determination of Accounting Standards,” The Accounting Review, Vol. 53, No. 1, 1978, pp. 112-134.

- S. Henderson, P. Graham and R. Brown, “Financial Accounting Theory: Its Nature and Development,” 2nd Edition, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1992.

- O. E. Williamson, “Corporate Finance and Corporate Governance,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 43, No. 3, 1988, pp. 567-591. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1988.tb04592.x

- L. Donaldson and J. Davis, “Stewardship Theory or Agency Theory: CEO Governance and Shareholder Returns,” Australian Journal of Management, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1991, pp. 49-64. doi:10.1177/031289629101600103

- I. Kesner and D. Dalton, “Boards of Directors and the Checks and (Im)Balances of Corporate Governance,” Business Horizons, Vol. 29, No. 5, 1986, pp. 17-23. doi:10.1016/0007-6813(86)90046-7

- K. Ahmed, “CEO Duality and Accounting-Based Performance in Egyptian Listed Companies: A Re-Examination of Agency Theory Predictions,” Research in Accounting in Emerging Economies, Vol. 8, 2008, pp. 65-96. http://www.essex.ac.uk/ebs/research/working_papers/WP_08-07.pdf

- G. Davis, “Agents without Principles? The Spread of the Poison Pill through the Inter-Corporate Network,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 4, 1991, pp. 583- 613. doi:10.2307/2393275

- L. Rechner and D. Dalton, “CEO Duality and Organizational Performance: A Longitudinal Analysis,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1991, pp. 155-160. doi:10.1002/smj.4250120206

- C. W. Chia, J. B. Lin and Y. Bingsheng, “CEO Duality and Firm Performance: An Endogenous Issue,” Corporate Ownership & Control, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2008, pp. 58-65.

- L. Levy, “Reforming Board Reform,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 59, No. 1, 1981, pp. 166-172.

- N. Dayton, “Corporate Governance: The Other Side of the Coin,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 62, 1984, pp. 34-37.

- D. J. Denis, D. K. Denis and A. Sarin, “Agency Theory and the Influence of Equity Ownership Structure on Corporate Diversification Strategies,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 20, No. 11, 1999, pp. 1071-1076. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199911)20:11<1071::AID-SMJ70>3.0.CO;2-G

- M. R. Kehoe, “Franchising, Agency Problems, and the Cost of Capital,” Applied Economics, Vol. 28, No. 11, 1996, pp. 1485-1493. doi:10.1080/000368496327741

- V. Krishnan and C. H. Loch, “A Retrospective Look at Production and Operations Management Articles on New Product Development,” Production and Operations Management, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2005, pp. 433-441. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2005.tb00231.x

- M. Lubatkin, P. Lane, S. O. Collin and P. Very, “Origins of Corporate Governance in the USA, Sweden and France,” Organization Studies, Vol. 26, No. 6, 2005, pp. 867- 888.

- E. F. Fama, “Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm,” The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 88, No. 2, 1980, pp. 288-307. doi:10.1086/260866

- H. F. Stettler, “Auditing Principles, Englewood Cliffs,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 1977.

- R. E. Freeman, “A Stakeholder Theory of Modern Corporations,” In: Ethical Theory and Business, Prectice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2004, pp. 56-65.

- R. E. Freeman, “Strategic Management,” Pitman, Boston, 1984.

- A. L. Friedman and S. Miles, “Stakeholders: Theory and Practice,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006.

- R. Gray, D. Owen and C. Adams, “Accounting and Accountability,” Prectice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 1996.

- A. Ullmann, “Data in Search of a Theory: A Critical Examination of the Relationships among Social Performance of US Firms,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1985, pp. 540-557.

- R. Roberts, “Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Application of Stakeholder Theory,” Accounting, Organisation and Society, Vol. 17, No. 6, 1992, pp. 595-612. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(92)90015-K

- J. C. Collins, “Good to Great,” Harper Collins, New York. 2001.

- J. C. Collins and J. I. Porras, “Built to Last,” Harpe Collins, New York, 1994.

- R. E. Freeman, C. W. Andrew and B. Parmar, “Stakeholder Theory and The Corporate Objective Revisited,” Organization Science, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2004, pp. 256-265. doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0066

- A. Etzioni, “A Communitarian Note on Stakeholder Theory,” Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1998, pp. 679- 691. doi:10.2307/3857547

- K. E. Goodpaster, “Business Ethics and Stakeholder Analysis,” Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1991, pp. 62-75.

- L. Donaldson and J. H. Davis, “CEO Governance and Shareholder Returns: Agency Theory or Stewardship Theory,” Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Washington, 1989, pp. 49-63.

- J. H. Davis, F. D. Schoorman and L. Donaldson, “Toward a Stewardship Theory of Management,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, No. 1, 1997, pp. 20-47.

- P. Block, “Stewardship: Choosing Service over Self-Interest,” Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, 1996.

- C. Caldwell and R. Karri, “Organizational Governance and Ethical Choices: A Covenantal Approach to Building Trust,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2005, pp. 249-259. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-1419-2

- C. Argryis, “Integrating the Individual and the Organization,” Wiley, New York, 1964.

- R. Walton, “From Control to Commitment in the Workplace,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 63, No. 4, 1985, pp. 77-84.

- C. M. Daily, D. R. Dalton and A. A. Canella, “Corporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2003, pp. 371-382.

- A. Shleifer and R. W. Vishny, “A Survey of Corporate Governance,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 52, No. 2, 1997, pp. 737-783. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

- L. T. Hosmer, “The Ethics of Management,” Irwin, Chicago, 1996.

- M. L. Peggy and M. O. Hugh, “Ownership Structures and R & D Investments of US and Japanese Firms: Agency and Stewardship Perspectives,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2001, pp. 212-225.

- H. C. Ronald, “The Nature of the Firm,” Economica, Vol. 4, No. 16, 1937, pp. 386-405.

- O. E. Williamson, “The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting,” The Free Press, New York, 1985.

- M. C. Suchman, “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches,” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1995, pp. 571-610.

- U. S. Krishna and C. K. Das, “Integrating Multiple Theories of Corporate Governance: A Multi-Country Empirical Study,” Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceeding, 2005, pp. 1-6.

- P. J. D. Maggio and W. W. Powell, “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, 1983, pp. 147-160. doi:10.2307/2095101

- M. E. Kathleen, “Agencyand Institutional-Theory Explanations: The Case of Retail Sales Compensation,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3, 1988, pp. 488-511. doi:10.2307/256457

- W. Seal, “Management Accounting and Corporate Governance: An Institutional Interpretation of the Agency Problem,” Management Accounting Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2006, pp. 389-408. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2006.05.001

- G. Hofstede and G. Hofstede, “Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind,” McGraw Hill, New York, 2004.