Green and Sustainable Chemistry

Vol.4 No.2(2014), Article ID:45943,8 pages DOI:10.4236/gsc.2014.42013

Effect of TiO2 Crystallite Diameter on Photocatalytic Water Splitting Rate

Haruna Banno1, Ben Kariya2, Norifumi Isu3, Muneaki Ogawa1, Saeko Miwa1, Keisuke Sawada1, Junki Tsuge1, Shoichiro Imaizumi1, Hidenori Kato1, Kyota Tokutake1, Seiichi Deguchi1

1Department of Energy Engineering and Science, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

2School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, USA

3Kitchen and Bathroom Technology Research Institute, LIXIL Corporation, Tokoname, Japan

Email: deguchi@nuce.nagoya-u.ac.jp

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 30 October 2013; revised 2 February 2014; accepted 15 March 2014

Abstract

The effect of (Pt-loaded)TiO2 crystallite diameter (i.e. Scherrer size) on the photocatalytic water splitting rate was investigated. (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powders with a wide range of crystallite diameters from about 16 to 45 nm with a blank region between about 23 and 41 nm were prepared by various annealing processes from an identical TiO2 powder. Water splitting experiments with these powders were carried out with methanol as an oxidizing sacrificial agent. It was found that the photocatalytic water splitting rate was sensitively affected by the crystallite diameter of the (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powder. More concretely, similar steep improvements of photocatalytic water splitting rates from around 15 and a little over 2 to about 30 μmol·m−2·hr−1 were obtained in the two (Pt-loaded)TiO2 crystallite diameters ranging from 16 to 23 and from 41 to 45 nm, respectively.

Keywords:Photocatalytic Water Splitting, TiO2 Crystallite Diameter, Scherrer Size, X-Ray Diffraction, Critical Water Anneal

1. Introduction

The primary components for photocatalytic water splitting are photocatalysts with a metal loaded for inducing the Schottky effect, water and oxidizing sacrifice agents to scavenge the coproduced oxygen gas, preventing the reverse reaction of oxygen with hydrogen to water [1] -[4] . In contrast to commonly used water-soluble oxidizing sacrifice agents such as saccharides and alcohols, previous work indicated suitability of water-insoluble castor-oil, which has the added benefit of being a nonfood natural hydrocarbon, and helps enable carbon-neutral photocatalytic water splitting [5] .

Regarding photocatalysts, TiO2 is still the most promising material due to its band structure that is especially well suited for water splitting. As band gaps of TiO2 are 3.0 and 3.2 eV in anatase and rutile forms, their excitations require ultraviolet light of less than 400 and 380 nm in wavelength, respectively. Many have attempted to enable visible light induction in TiO2 via doping metals or nonmetal ions [6] -[9] . However, the benefits are currently far outweighed by the complex manufacturing methods, high costs, instability issues, etc.

Our group has focused on increasing the crystallite diameter of TiO2 powder in order to improve its quantum efficiency. Ohtani and co-workers have already reported improving photocatalytic water splitting rates by increasing crystallite diameters of anatase TiO2 with loading Pt in 2 wt% [10] , however only crystallite sizes in the range of about 20 to 30 nm and around 55 nm were studied. Since our group recently invented novel annealing processes utilizing thermo fields of subor super-critical water with dissolving or undissolving metal-salts [11] - [13] , supplementing experiments to cover the TiO2 crystallite size ranges, where Ohtani and co-workers could not prepare, have been ready to be performed.

In this study, TiO2 powders with a wide range of crystallite diameters were prepared by various annealing processes from an identical starting TiO2 powder. After Pt loading to the prepared TiO2 powders, photocatalytic water splitting experiments were performed. Measured hydrogen producing rates were assessed with respect to the (Pt-loaded)TiO2 crystallite diameters (i.e. Scherrer sizes) determined from their X-ray diffraction patterns and the Scherrer’s equation [14] . Finally, future strategies for further enhancement of photocatalytic water splitting rates were discussed particularly in terms of selection of the starting TiO2 powders and operating parameters for their annealing and Pt loading to them.

2. Experimental Apparatus and Procedures

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the experimental apparatus for photocatalytic water splitting [5] . The main reactor was made of Pyrex glass in a cylindrical shape with 90 mm internal diameter, 40 mm tall and a volume of about 255 mL. The cylinder had two taps for replacing air inside initially by Ar-gas and sampling produced-gas intermittently throughout the experiment. The top cover was made of solid quartz glass with high transmissivity toward ultraviolet rays. To maintain a constant reaction temperature, a cooling chamber was attached to the bottom of the cylinder, where water at 298 K was circulated.

The starting TiO2 powders utilized were ST-01(anatase form) manufactured by Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha, Ltd. Japan. First, 1.0 g of TiO2 powder was grinded for 60 min in an automatic grinder (ANM1000, Nitto Kagaku Co., Ltd., Japan), then inserted into a 1/2-inch-SUS304 annealing tube as shown in Figure 2 together with 3.0 mL of water and 1.0 g of NaCl, where ionic bonding metal-salts had been found to contribute to increase TiO2 crystallite diameter in previous works [11] [12] . After dissolving the added salt, the tube was completely sealed. Before the annealing treatment, the whole tube was soaked in a water bath of an ultrasonic washing device (US-5, SND, Japan, bath volume: 20 L, ultrasonic frequency: 38 kHz, output power: 300 W), and then ultrasonic wave was irradiated for 30 min to disperse all adhering powders isolated each other inside the tube. The annealing tube was heated in an electric furnace (MMF, AS ONE, Japan) to 660 K at a constant heating rate of 6.0 K min-1 and then held for 1 hr, taking into consideration the critical temperature of water at 647.3 K. The pressure inside the SUS tube was calculated to be 26.1 MPa [15] , which is well above the critical pressure of water at 22.1 MPa. After these procedures, the power supply to the furnace was cut, and then the tube was spontaneously cooled down to room temperature in the furnace.

As comparative annealing treatments, following two operations were implemented. The annealing tube prepared by the same procedures mentioned in the foregoing paragraph was quickly introduced into the preheated furnace at 660 K and then quenched in a sufficiently big water bath down to room temperature after a holding time of 1 hr. And, the annealing tube involving only 1.0 g of TiO2 powder was handled in the same thermal history described in the foregoing paragraph.

The treated TiO2 powder was washed by de-ionized water, and dried in a vacuum oven (VO-320, Advantec Toyo Kaisha, Ltd., Japan) at 373 K for 24 hrs. And then, measurements were carried out with a laser diffraction/scattered devise (LA-920, Horiba, Japan, ultrasonic frequency: 22.5 kHz, output power: 30 W) for a size distribution, and an X-ray diffraction (RINT2500TTR, Rigaku Denki, Japan) for a crystallite diameter (i.e. Scherrer size) calculated by the Scherrer’s equation [14] . Here, size distributions of any powders utilized in this

Figure 1. Schematic of experimental apparatus for water splitting.

Figure 2. Schematic of annealing SUS-tube.

study were found almost the same. Then, 0.1 wt% of Pt was loaded to the TiO2 powder by photodeposition of hexachloroplatinic acid according to preparation methods found in literatures [16] [17] . Since the crystallite diameters of TiO2 powder before and after Pt loading were different, the crystallite diameters of the (Pt-loaded) TiO2 powders were used for arranging and analyzing the data obtained for photocatalytic water splitting experiments.

As for the water splitting experiments, 5.0 mL of 50.0 vol% methanol solution was poured into the reactor with 0.50 g of Pt/TiO2 powder. Then, after replacing air inside the reactor by Ar-gas and starting the circulation of water at 298 K in the cooling chamber, the light irradiation by a black light (EFD15BLB-T, 15.0 W, Toshiba Lighting & Technology Corporation, Japan) was initiated. Finally, hydrogen concentration inside the gas phase of the reactor was periodically measured by means of TCD gas-chromatography (GC-8A, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). Due to these procedures, experimental repeatability could be conveniently preserved.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystallite Diameters of TiO2 Powders Due to Different Annealing Treatments

Figure 3 compares XRD patterns of the annealed TiO2 powders together with the starting TiO2 powder of ST-01. Here, abbreviations of 0, conv., SCW, mod. and rap. denote starting material, conventional under air atmosphere without water and NaCl, super-critical water, moderate and rapid temperature changes, respectively. The similarities of the XRD patterns suggested that the annealing treatments had no influence on the chemical composition of the TiO2 powder.

Table 1 summarizes detailed annealing parameters and crystallite diameters calculated by the Scherrer’s equation using the characteristic values of respective XRD peaks at around 25.3 degrees. Compared to the starting TiO2 powder, larger crystallite diameters were always observed in the annealed TiO2 powders regardless of the operating conditions. Among the annealed TiO2 powders, the crystallite diameter annealed via the conventional technique was smaller than those obtained with the invented annealing techniques using critical water and/or NaCl [11] [12] , meaning sufficient evidences for superiority of the invented critical water annealing processes.

Figure 3. XRD patterns of TiO2 powders.

Table 1. Crystallite diameters (i.e. Scherrer sizes) of TiO2 powders.

3.2. Crystallite Diameter Comparisons between TiO2 and Pt/TiO2 Powders

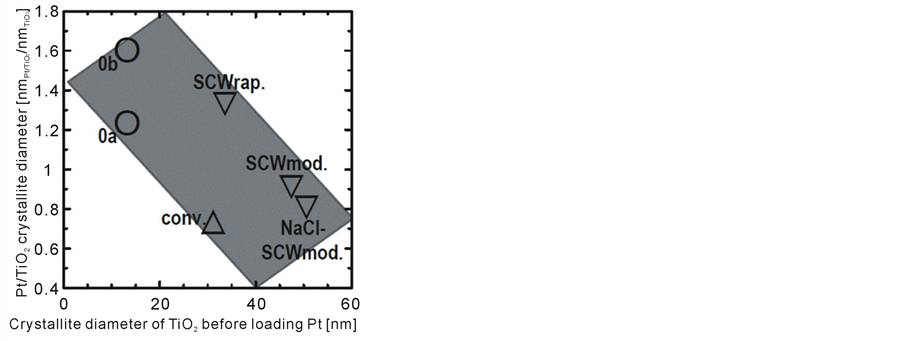

As described above, Pt loading treatments affected crystallite diameters of the (Pt-loaded) TiO2 powders. Table 2 shows all crystallite diameters of the Pt/TiO2 powders together with those before Pt loading as already shown in Table 1. To find the effect of Pt loading treatments on the crystallite diameters of TiO2 powders, Figure 4 shows crystallite diameters of Pt/TiO2 powders divided by those of the respective TiO2 powders before Pt loading.

This figure roughly indicates inversely proportional relation in the crystallite diameters of TiO2 and Pt/TiO2 powders. Furthermore, it can be seen that difference of the crystallite diameters in Pt/TiO2 powders prepared from the same TiO2 powder is not a negligible quantity (see 0a and 0b in Table 2 and Figure 4) on account of different experimenters. It is fairly common in photocatalytic reactions to obtain such inconsistent results, however the invented annealing processes are prodigious to give strong data repeatability for all inorganic powders [11] -[13] . Consequently, differing crystallite diameters of the (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powders prepared from the same TiO2 powder such as 0a and 0b could be attributed to fine procedural inconsistencies during Pt loading treatments such as the time duration of various steps, position of the black light affecting ultraviolet intensity to TiO2 powder, and stirring intensity.

3.3. Water Splitting by Pt/TiO2 Powders with Various Crystallite Diameters

Figure 5 shows hydrogen producing rates by photocatalytic water splitting with crystallite diameters of (Ptloaded) TiO2 powders ranging from 16 to 23 and from 41 to 45 nm together with superimposing a fruitful figure from a reference literature [10] . It can be seen that hydrogen producing rates were increased steeply towards the crystallite diameter of (Pt-loaded) TiO2 powder in the above-mentioned two ranges. Quantitatively

Table 2 . Crystallite diameters of TiO2 powders before and after loading Pt.

Figure 4. XRD patterns of TiO2 powders.

Figure 5. XRD patterns of TiO2 powders.

hydrogen producing rates were increased from around 15 and a little over 2 to about 30 μmol·m−2·hr−1 with slight increments of the crystallite diameter of (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powder in the order of a few nanometers for respective ranges.

Such steep increments resemble the results on the superimposed figure in Figure 5 at around 20 nm of anatase TiO2 crystallite sizes obtained by Ohtani and co-workers [10] , approaching to a local maximum hydrogen producing rate of about 75 μmol·hr−1. However, it can also be seen that this rate has been unchanged for relatively wide range in about 10 nm of anatase TiO2 crystallite sizes from about 20 to 30 nm, and then a champion rate about 120 μmol·hr−1 discretely reveals at around 55 nm of TiO2 crystallite size [10] .

Concerning relations among crystallite diameters, lattice defects (such as vacancies, impurities and dislocations) and band structures (such as highest occupied molecular orbital, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital and their difference so-called a band-gap) of TiO2 powders, the followings are commonly endorsed [17] [18] : lattice defects broaden a band-gap range, smaller crystallite diameters enlarge a band-gap itself so-called a blue-shift, crystallite diameter increments bring with decreases of any lattice defects, and so on. Hence, increasing crystallite diameters of anatase ST-01 powders may result in approaching 3.2 eV as pure anatase TiO2 on a single crystal state a whole volume of each powder having broad band-gaps originally. This can elucidate the results in Figure 5, that is to say, ST-01 crystallite diameter increments lead to contradictive enhancing and descending effects on photocatalytic water splitting rates. Concretely describing, the rate enhancements have been due to increasing ST-01 volume playing photocatalytic water splitting role gradually in accordance with decreasing their lattice defects, while the rate descents have been owing to narrowing the band-gaps approaching to 3.2 eV, resulting to invalidation of the activating light intensity especially ranged from 380 to 400 nm. Such simultaneous effects of enhancing and descending photocatalytic water splitting rates due to increments of TiO2 crystallite diameters are supposed to result in discontinuous hydrogen producing rates towards crystallite diameters of the (Pt-loaded) TiO2 powders as shown in Figure 5.

In order to verify the above-mentioned mechanisms based on some assumptions, experiments with the (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powders in crystallite diameters from 23 to 41 and above 45 nm are indispensable, however it is so difficult to prepare mid-crystallite-sized (from 40 to 50 nm) TiO2 powders to borrow Ohtani and co-workers' phrases in their paper [10] . Anyway, the authors succeeded to prepare the mid-crystallite-sized TiO2 powders of 41.17, 43.65 and 44.95 nm accurately. Furthermore, steep increments of hydrogen producing rates could be obtained with an increase in crystallite diameter of the (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powder as described-above. On the grounds of these outcomes, much further higher photocatalytic water splitting rates can be expected with a bit change of the (Pt-loaded)TiO2 crystallite diameter by using the invented novel annealing processes [11] [12] .

4. Future Strategies for Enhancing Photocatalytic Water Splitting Rate

As mentioned above, this study expanded Scherrer size ranges of Pt/TiO2 powders to some extent. However, the aforementioned blank regions from about 23 to 41 and above 45 nm remain to be studied. Tables 3 shows parameters of interest of Pt/TiO2 powders. In order to systematically study the relative effects of each parameter of interest on the resulting hydrogen production rate, the optimal Pt/TiO2 powder and its respective annealing treatment and Pt loading must first be determined.

There are many commercially prepared TiO2 powders as shown in Table 4. Previous works in literature point to P90, manufactured by Nippon Aerosil Co., Ltd., as the best commercially available photocatalyst for water splitting reactions [5] . Therefore, any further experimentation will utilize P90 (or any TiO2 powder subsequently deemed superior) as the TiO2 starting material.

Table 3 . Considerable operating parameters for varying (Pt-loaded)TiO2 crystallite diameters.

Table 4. Examples of commercial TiO2 and suitable applications confirmed by the authors so far.

5. Conclusion

Due to the novel critical water annealing process, (Pt-loaded)TiO2 powders with various crystallite diameters (i.e. Scherrer sizes) ranging from about 16 to 23 and 41 to 45 nm could be prepared. The photocatalytic hydrogen producing rate (water splitting rate) was enhanced from around 15 and a little over 2 to about 30 μmol·m−2·hr−1 with slight increments in crystallite diameter from 16 to 23 and from 41 to 45 nm, respectively. Further water splitting rate enhancements were concluded possible through optimization of crystallite diameters of (Pt-loaded)TiO2 and selection of an optimal TiO2 powder as a starting material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha, Ltd. for the generous supplies of ST-01 TiO2 powder. This work is supported by “General Sekiyu R&D Encouragement Assistance Foundation” and “Tanikawa Fund Promotion of Thermal Technology”. These financial supports are gratefully acknowledged. Finally, Seiichi Deguchi would like to express deep gratitude to the late Mr. Tatsumi Imura for his kindhearted encouragements and supports.

References

- Matsuoka, M., Kitano, M., Takeuchi, M., Tsujimaru, K., Anpo, M. and Thomas, J.M. (2007) Photocatalysis for New Energy Production: Recent Advances in Photocatalytic Water Splitting Reactions for Hydrogen Production. Catalysis Today, 122, 51-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2007.01.042

- Nosaka, A.Y., Nishino, J., Fujiwara, T., Ikegami, T., Yagi H., Akutsu, H. and Nosaka, Y. (2006) Effects of Thermal Treatments on the Recovery of Adsorbed Water and Photocatalytic Activities of TiO2 Photocatalytic Systems. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 110, 8380-8385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp060894v

- Strataki, N., Bekiar, V., Kondarides, D.I. and Lianos, P. (2007) Hydrogen Production by Photocatalytic Alcohol Reforming Employing Highly Efficient Nanocrystalline Titania Films. Applied Catalysis B, 77, 184-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.07.015

- Deguchi, S., Shibata, N., Takeichi, T., Furukawa, Y. and Isu, N. (2010) Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Aqueous Solution of Various Oxidizing Sacrifice Agents. Journal of the Japan Petroleum Institute, 53, 95-100.

- Deguchi, S., Takeichi, T., Shimasaki, S., Ogawa, M. and Isu, N. (2011) Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Water with Nonfood Hydrocarbons as Oxidizing Sacrifice Agents. AIChE Journal, 57, 2237-2243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aic.12414

- Kapoor, P.N., Uma, S., Rodriguez, S. and Klabunde, K.J. (2005) Aerogel Processing of MTi2O5 (M=Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Zn, Sn) Compositions Using Single Source Precursors: Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Behavior. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical, 229, 145-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2004.11.008

- Lee, K., Lee, N.H., Shin, S.H., Lee, H.G. and Kima, S.J. (2006) Hydrothermal Synthesis and Photocatalytic Characterizations of Transition Metals Doped Nano TiO2 Sols. Materials Science and Engineering, 129, 109-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2005.12.032

- Ohno, T., Tsubota, T., Toyofuku, M. and Inaba, R. (2004) Photocatalytic Activity of a TiO2 Photocatalyst Doped with C4+ and S4+ Ions Having a Rutile Phase under Visible Light. Catalysis Letters, 98, 255-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10562-004-8689-7

- Yin, S., Aita, Y., Komatsu, M. and Sato, T. (2006) Visible-Light-Induced Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2-xNy Prepared by Solvothermal Process in Urea-Alcohol System. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 26, 2735-2742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2005.05.012

- Ohtani, B., Ogawa, Y. and Nishimoto, S. (1997) Photocatalytic Activity of Amorphous-Anatase Mixture of Titanium (IV) Oxide Particles Suspended in Aqueous Solutions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 101, 3746-3752. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp962702+

- Deguchi, S., Ogawa, M., Nowak, W., Wesolowska, M., Miwa, S., Sawada, K., Tsuge, J., Imaizumi, S., Kato, H., Tokutake, K., Niihara, Y. and Isu, N. (2013) Development of Superand Sub-Critical Water Annealing Processes. Powder Technology, 249, 163-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2013.08.013

- Deguchi, S. and Ogawa, M. (2011) Thermal Treatment of Metal-Compound Powders. PATENT in Japan, No. 2011- 202259.

- Sawada, K., Ogawa, M., Miwa, S., Tsuge, J., Imaizumi, S., Kato, H., Tokutake, K., Niihara, Y., Isu, N. and Deguchi, S. (2013) Superand Sub-Critical Water Annealing Processes. Proceedings of the International Symposium on EcoTopia Science 2013.

- Patterson, A.L. (1939) The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Physical Review, 56, 978-982. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.56.978

- Marshall, W.L. and Franck, E.U. (1981) Ion Product of Water Substance, 0-1000 degC, 1-10000 Bars, New International Formulation and Its background. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 10, 295-304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.555643

- Sato, S. and White, J.M. (1980) Photoassisted Water-Gas Shift Reaction over Platinized Titanium Dioxide Catalysts. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 102, 7206-7210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja00544a006

- Nakayama, M., Doguchi, T. and Nishimura, H. (1992) Photoreflectance Study of Hole—Subband Structures in GaAs/ InxAl1−xAs Strained-Layer Superlattices. Journal of Applied Physics, 72, 2372-2376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.351579

- Ube Industies, Ltd. (2012) Preparing Methods for Crystallized Titanium Oxides. PATENT in Japan, No. 2012-5999.

- Deguchi, S., Katsuki, R., Sugiura, Y., Takeichi, T., Shibata, N. and Isu, N. (2011) Induction by Visible Light of Photocatalytic Water Decontamination by Use of Powders of Nonlinear Optic Material and Visible-Light Phosphor to Generate Dispersed Ultraviolet Light. Kagaku Kogaku Ronbunshu, 37, 38-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1252/kakoronbunshu.37.38

- Deguchi, S., Sugiura, Y., Shibata, N., Katsuki, R., Takeichi, T. and Isu, N. (2011) Photocatalytic Water Decontamination with Dispersed Light Source of Ultraviolet Electroluminescence Powder. Kagaku Kogaku Ronbunshu, 37, 42-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1252/kakoronbunshu.37.42

- Deguchi, S., Kobayashi, N. and Kubota, M. (2008) Environmental Purifying Materials, Equipment and Method. PATENT in Japan, No. 2008-194622.