Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine

Vol.4 No.9(2014), Article

ID:49548,6

pages

DOI:10.4236/ojvm.2014.49024

Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology in the Diagnosis of Canine Cutaneous Transmissible Venereal Tumor— Case Report

Noeme Sousa Rocha1, Tália Missen Tremori1*, João Alexandre Matos Carneiro2

1Departament of Veterinary Clinic, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science-UNESP, Botucatu, Brazil

2Department of Animal Reproduction and Veterinary Radiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science-UNESP, Botucatu, Brazil

Email: *talia_missen@hotmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 16 July 2014; revised 10 August2014; accepted 20 August 2014

ABSTRACT

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has been widely used in the diagnosis of lesions from various origins, especially neoplastic. The technique is simple, fast, safe, minimally invasive and inexpensive, which allows through the evaluation of cell morphology to establish prognosis, delineate surgical margins, monitor lesion growth, validate indication euthanasia during surgery and monitor chemotherapy protocols. Diagnosis of canine transmissible venereal tumor (TVT) can be accomplished with ease and precision, even to be rated, according to the degree of aggressiveness. The study objective was to demonstrate the effectiveness of the examination in the diagnosis of TVT plasmacytoid type. An eight-month dog presented to the veterinary hospital (HV), faculty of veterinary medicine and animal science, FMVZ, UNESP-Univ Estadual Paulista with clinical suspicion of cutaneous lymphoma. By presenting multiple nodular lesions, FNAC was performed to cytological diagnosis. The tissue showed cells consistent with TVT. The animal was treated, and a total cure was achieved. According to the literature, TVT mainly affects external genitalia of sexually active animals and its transmission is more frequent during intercourse. In addition, animals sexually immature and without contact to the street dogs, hardly have injuries by TVT. In this case, verrucous and ulcerated lesions on the vulva of its mother during pregnancy and childbirth infected the animal. Diffuse and predominant dorsal injuries occurred due to both exfoliation of breast tumor during delivery and immunosuppression of pup at birth, thus favoring an atypical transmission.

Keywords:Cytological Diagnosis, TVT, Atypical Transmission

1. Introduction

Use of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in human medicine stems from the nineteenth century; however, veterinary medicine began to be employed only in the late 1980s. Currently FNAC has been widely employed in the diagnosis of lesions from various origins, but mainly in cancer [1] . For cell morphology evaluation, the technique allows differentiating inflammatory processes, hyperplasias, neoplasms and metastasis sites. Likewise, it permits establishing and grading prognoses, according to the degree of aggressiveness, monitoring and managing chemotherapy treatments, defining surgical margins, following the lesion growth, and validating indication for euthanasia during surgery [2] . The main FNAC limitation, unlike the histopathological examination, is related to the impossibility to obtain data on the architecture of lesion, but provides a diagnostic result with greater ease. However, both techniques complement each other [3] .

The definitive diagnosis of transmissible venereal tumor (TVT) is based on its physical examination and typical cytological features in exfoliated cells obtained from swab, fine-needle aspiration or impression. Histopathology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and immunohistochemical staining for diagnosis can also be performed [4] -[6] .

The TVT in dogs, also known as Sticker tumor, canine condyloma, venereal granuloma, sarcoma infectious and transmissible lymphosarcoma, is classified as reticuloendothelial benign tumor of round cells. Because of its contagious character [7] , TVT mainly affects the external genitalia and occasionally, internal genital organs [8] .

Infection and transmission happen mainly through intercourse [8] , being more common in young sexually mature animals [9] . Due to exfoliation on affected region from the sick animal, an atypical neoplastic cell infection occurs on healthy individuals [10] [11] . These may grow slowly over years and become invasive, eventually changing to malignant and metastatic [4] [12] .

Upon genitalia examination, males generally have tumors cranially located on the glans, and preputial bulb and mucosa [13] , with a consequent phimosis [14] . In females, TVT is located in the caudal vagina and vaginal vestibule, but rarely found in the uterine region. Generally, its projection from the vulva causes deformation of the perineal region without interfering with urination [15] . Ulcerated lesions in male external organs taking place with hemorrhagic discharges usually mystified with urethritis, cystitis and prostatitis [9] . In females, such lesions can cause anemia [15] .

Tumor can also be transmitted to other regions by dog habit of smelling and licking [16] . In the veterinary literature, the occurrence of metastasis from genital TVT affecting nasal or oral mucosa, skin, subcutaneous tissue, eyes, internal organs and central nervous system has been reported [4] [17] [18] being between 5% - 17% of cases [5] [9] . Diagnosis is complicated due to the diversity of clinical signs, frequent in other diseases, varying according to the affected area [9] .

Treatments applied to TVT include surgery, immunotherapy, biotherapy and chemotherapy [9] [19] [20] . The success rate approaches 100% when initiated no later than one year of the disease evolution. After this, the treatment becomes longer, and a more complete remission of lesions is impaired [21] .

An 8-month-old male mongrel dog, showing diffuse nodular skin lesions and clinical suspicion of cutaneous lymphoma, was referred to the veterinary hospital (HV) of the faculty of veterinary medicine and animal science, FMVZ, UNESP-Univ Estadual Paulista, to diagnostic by means of cytological examination.

The FNAC technique was employed. To do so, 10-ml syringes and 22-gauge needles were used, coupled to a Valeri Aspirgun.

The sampling area was submitted to antisepsis. Then, specimens were obtained from the puncture site through continuous aspiration and repositioning of the needle “in range”. Upon sampling completion, smears were made with the expelled contents of the needle on microscope slides. Samples were stained by two methods. For Papanicolaou method, slides were submerged in 95% ethanol. For Romanowsky system, slides were air dried and fixed in methanol [22] . Cytomorphological diagnosis was made by light microscopy, with 400× of magnification.

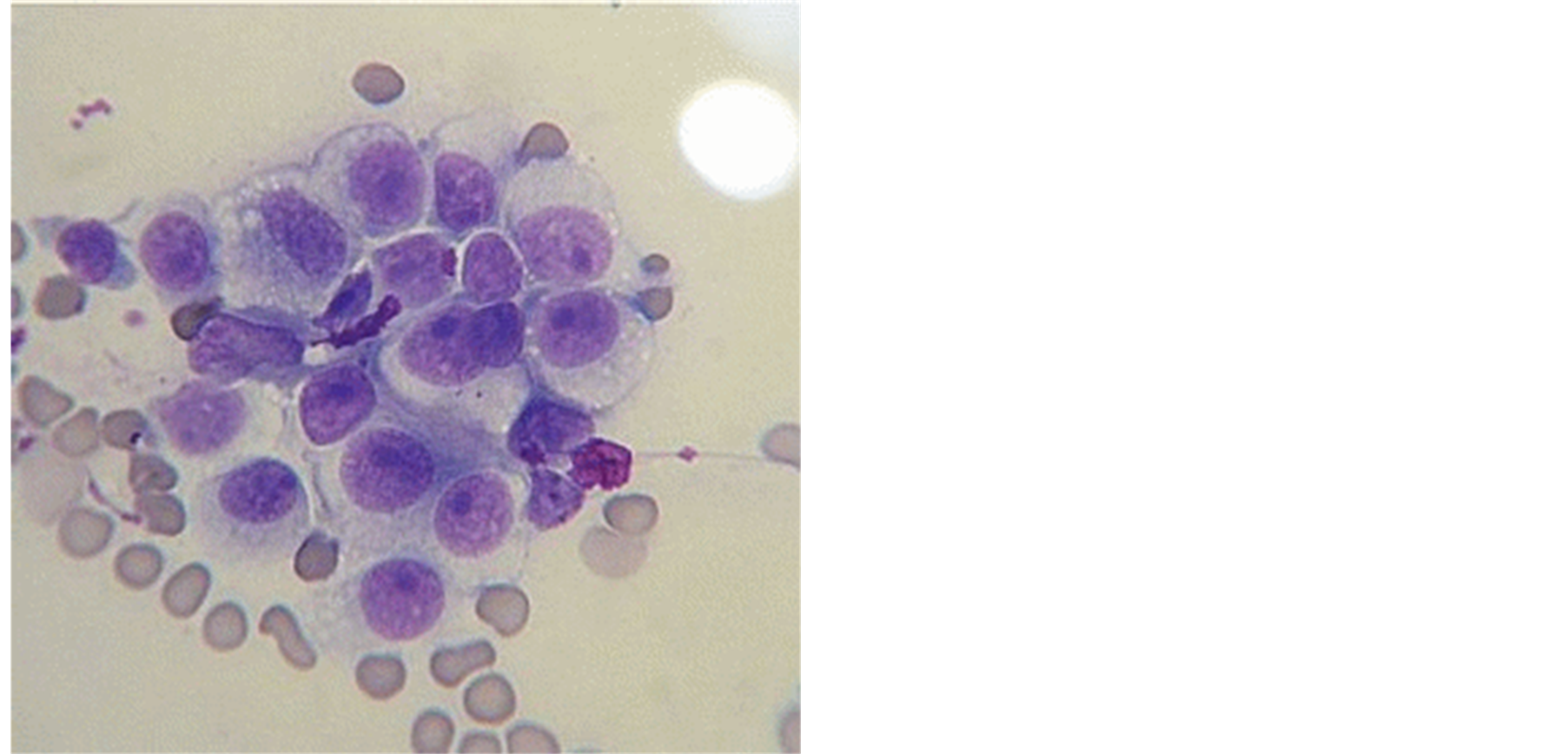

The animal here reported was diagnosed with plasmacytoid tumor, and forwarded to the Office of Small Animal Surgery HV-FMVZ for treatment initiation (Figure 1).

2. Discussion

FNAC is widely used in clinics for being a simple, safe, quick, low-cost, minimally invasive and painful method, which helps to preserve cellular morphology [23] -[26] . Moreover, this technique has high accuracy for TVT diagnosis [27] -[30] and the monitoring of treatment [25] [31] regarding genital and extragenital tumors [29] . Likewise, it enables to carry out multiple sampling in series, which eventually allows excluding inconclusive results, or confirming suspicion of injury recurrence [22] .

The case described was diagnosed by FNAC as cutaneous TVT despite extragenital location, specifically in the skin, which occurs rarely [32] . Cutaneous metastasis, described by some authors, was discarded because the animal, besides being sexually inactive, had neither injuries to external genitalia, nor access to other dogs. The likely explanation is a direct transmission from mother to pup after social interactions [33] , through inoculation of neoplastic cells from its vaginal TVT in the form of skin microlesions [34] . Multiple nodules located throughout dorsal extension of the animal were related to immunological immaturity, since immunocompetence has a fundamental role in tumor growth and expansion [35] .

With the exception of not being ulcerated, animal lesions resemble those described in the literature as the most common: verrucous or nodular, single or disseminated [36] , with an ulcerated and friable surface when developing a more aggressive behavior. The lesion diameter can reach up to 6 cm [23] [37] [38] . Other authors described tumor as a “donut” shape, from 2 to 5 cm, embossed, well-defined, having a non-ulcerated portion with yellowish-white circumscribed by a red or brown peripheral zone [36] [39] . They are usually located on the back, left flank, and forehead region adjacent to the lower lip [39] .

The cytological features of the skin nodules showed the same characteristics of genital tumors, corroborating the literature [39] .

Upon microscopic examination, the tumor cells present the following features: rounded or oval form, diameter between 14 and 30μm, slightly basophilic cytoplasm with well-defined edges and small clear vacuoles, a nucleus of round or oval shape with irregular or granular chromatin, and one or two prominent nucleoli [40] . anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are also verified as megakaryocytic and nuclear hyperchromasia [25] .

Mitotic forms and inflammatory cells resulting from surface ulcerations and bacterial invasion are also identified in TVT cytological sample as neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes [25] [40] -[42] . Atypical aspects of TVT cells can be observed in tumors with longer evolution, and cellular changes can be identified in cases of primary tumors and metastasis [32] [42] .

Figure 1. Cells of transmissible venereal tumor (TVT) plasmacytoid. Giemsa. 1000×.

Morphological differences are due to different mitochondrial DNA sequences existing in cell lines of TVT [42] . Therefore, as a result of morphological evaluation during cytological examination, tumors can be differentiated and classified from different lineages as plasmacytoid, linphocitoyd, and mixed [29] [43] . Ovoid cells with eccentric nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, and numerous clear cytoplasmic vacuoles, are about 60% of the cell population of plasmacytoid tumors. Linphocitoyd tumor subtype has predominance of round cells, and its cytoplasm is sparse and finely granular, with few vacuoles in their peripheral region. The core features in the center, rounded, with irregular chromatin, and one or two prominent nucleoli. When both cell morphologies are present in similar amounts, tumor is considered as a mixed subtype [29] .

Determination of tumor subtype is important for establishing animal prognosis and treatment. Due to high frequency anomalies and high nuclear expression of P-glycoprotein, plasmacytoid TVT has a greater aggressiveness, lower remission rate, and frequent metastasis [29] [44] [45] . This protein promotes the efflux of chemotherapeutic agents and reduces the intracellular drug concentration, inducing chemoresistance [46] -[48] .

3. Conclusions

The variety of tumor subtypes, in addition to an unusual anatomical location, complicates clinical suspicion of primary cutaneous TVT, especially when atypical lesions and the animal clinical history are often incompatible with the routine. However, in this case, the use of FNAC was fundamental for determining the TVT subtype, which allowed a suitable diagnosis, and the establishment of an appropriate treatment and prognosis.

Acknowledgements

CAPES (Brazil) for the financial support.

References

- Magalhaes, A.M., Ramadinha, R.R., Barros, C.S.L. and Peixoto, P.V. (2001) Comparative Study between Cytopathology and Histopathology in the Diagnosis of Canine Cancer. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira, 21, 23-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2001000100006

- Ghisleni, G., Roccabianca, P., Ceruti, R., Stefanello, D., Bertazzolo, W., Bonfanti, U. and Caniatti, M. (2006) Correlation between Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology and Histopathology in the Evaluation of Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Masses from Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Clinical Pathology, 35, 24-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-165X.2006.tb00084.x

- Zuccari, D.A.P.C., Santana, A.E. and Roch, N.S. (2001) Fine Needle Aspiration Cytological and Histologic Correlation in Canine Mammary Tumors. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science, 38, 38-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-95962001000100007

- Moulton, J.E. (1978) Tumor of Genital Systems. In: Moulton, J.E., Ed., Tumors in Domestic Animals, 2nd Edition, University of California, California, 326-330.

- Richardson, R.C. (1981) Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practising Veterinarian, 3, 951-956.

- Daleck, C.L.M., Ferreira, H.I., Daleck, C.R., et al. (1987) Further Studies on the Treatment of Canine Transmissible Venereal. Ars Veterinaria, 3, 203-209.

- Goldschmidt, M.H. and Hendrick, M.J. (2002) Tumors of the Skin and Soft Tissues. In: Meuten, D.J., Ed., Tumors in Domestic Animals, 4th Edition, Iowa State Press, Ames.

- Calvert, C.A. (1983) Transmissible Venereal Tumor in the Dog. In: Kirk, R.W., Ed., Current Veterinary Therapy VIII, W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia.

- Rogers, K.S. (1997) Transmissible Venereal Tumor. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practising Veterinarian, 19, 1036-1045.

- Cohen, D. (1985) The Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor: A Unique Result of Tumor Progression. Advances in Cancer Research, 43, 75-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-230X(08)60943-4

- Johnston, S.D. (1991) Performing a Complete Canine Semen Evaluation in a Small Animal Hospital. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 21, 545-551.

- Lombard, C.H. and Cabanie, P. (1968) Le sarcome de Sticker. Revue de Médecine Vétérinaire, 119, 565-586.

- Higgins, D.A. (1966) Observations on the Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor as Seen in the Bahamas. Veterinary Record, 79, 67-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.79.3.67

- McEvoy, G.K. (1987) American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information. American Society of Hospital and Pharmacists, Bethesda, MD.

- Aprea, A.N., Allende, M.G. and Idiard, R. (1994) Intrauterine Transmissible Venereal Tumor: A Case Description. Vet Argentina XI, 103, 192-194.

- Mukaratirwa, S. and Gruys, E. (2003) Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor: Cytogenetic Origin, Immunophenotype, and Immunobiology. A Review. Veterinary Quarterly, 25, 101-111.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2003.9695151 - Brown, N.O., MacEwen, E.G. and Calvert, C.A. (1981) Transmissible Venereal Tumor in the Dog. California Veterinary, 3, 6-10.

- Tinucci-Costa, M., Souza, F.F., Léga, E., et al. (1997) Puncturing Marrow Is Important in the Prognosis of Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Pathology, 33, 143.

- Weir, E.C., Pond, M.J., Duncan, J.R., et al. (1987) Extragenital Located TVT Tumor in the Dog. Literature Review and Case Reports. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 14, 532-536.

- Johnson, C.A. (1994) Genital Infections and Transmissible Venereal Tumor. In: Nelson, R.W. and Couto, C.G., Eds., Fundamentos de Medicina Interna de Pequenos Animais, Guanabara Koogan, Rio de Janeiro, 525.

- Boscos, C.M. and Ververidis, H.N. (2004) Canine TVT: Clinical Findings, Diagnosis and Treatment. Scientific Proceedings WSVA-FECAVAHVMS World Congress, Rhodes, 2, 758-761.

- Raskin, R.E. and Meyer, D.J. (2003) Cytology Atlas of Dogs and Cats. Roca Ltda, Sao Paulo.

- Schlafer, D.H. and Miller, R.B. (2007) Female Genital System. In: Maxie, M.G., Ed., Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol. 3, Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, 429-564.

- Daleck, C.L.M., Daleck, C.R., Pinheiro, L.E.L., Bechara, G.H. and Ferreira, H.I. (1987) Evaluation of Different Diagnostic Methods of Transmissible Venereal Tumor (TVT) in Dogs. Ars Veterinaria, 3, 187-194.

- Erünal-Maral, N., Findik, M. and Aslan, S. (2000) Use of Exfoliative Cytology for Diagnosis of Transmissible Venereal Tumor and Controlling the Recovery Period in the Bitch. Deutsche Tierarztliche Wochenschrift, 107, 175-180.

- Bassani-Silva, S., Amaral, A.S., Gaspar, L.F.J., Rocha, N.S., Portela, R.F., Jeison, S.S., Teixeira, C.R. and Sforcin, J.M. (2003) Transmissible Venereal Tumor—Review. Journal of Pet Food & Health & Care, 2, 77-82.

- Ogilvie, G.K. and Moore, A.S. (1995) Managing the Veterinary Cancer Patient—A Practice Manual. Veterinary Learning Systems, USA, 37-51.

- Meyer, D.J. and Franks, P. (1986) Clinical Cytology—Cytological Characteristics of Tumors. Modern Veterinary Practice, 1, 440-445.

- Amaral, A.S., Gaspar, L.F.J., Bassani-Silva, S. and Rocha, N.S. (2004) Cytological Diagnosis of Transmissible Venereal Tumor in the Region of Botucatu, Brazil (Descriptive Study: 1994 to 2003). Revista Portuguesa de Ciências Veterinárias, 99, 167-171.

- Meinkoth, J.H. and Cowell, R.L. (2002) Sample Collection and Preparation in Cytology: Increasing Diagnostic Yield and Recognition of Basic Cell Types and Criteria of Malignancy. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 32, 1187-1235.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0195-5616(02)00049-9 - Batamuzi, E.K. and Kessy, B.M. (1993) Role of Exfoliative Cytology in the Diagnosis of Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 34, 399-401.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.1993.tb02732.x - Ferreira, A.J., Jaggy, A., Varejao, A.P., Ferreira, M.L., Correia, J.M., Mulas, J.M., Almeida, O., Oliveira, P. and Prada, J. (2000) Brain and Ocular Metastasis from a Transmissible Venereal Tumor in a Dog. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 41, 165-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2000.tb03187.x

- Moutinho, F.Q., Sampaio, G.R., Teixeira, C.R., Sequeira, J.L. and Laufer, R. (1995) Transmissible Venereal Tumor with Skin Metastases in a dog. Ciência Rural, 25, 469-471.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84781995000300025 - Marcos, R., Santos, M., Marrinhas, C. and Rocha, E. (2006) Cutaneous Transmissible Venereal Tumor without Genital Involvement in a Prepubertal Female Dog. Veterinary Clinical Pathology, 35, 106-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-165X.2006.tb00097.x

- Cohen, D. (1973) The Biological Behavior of TVT in Immunosuppressed Dogs. European Journal of Cancer, 3, 163- 164.

- Theilen, G.H. and Madewell, B.R. (1979) Tumors of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue. In: Theilen, G.H. and Madewell, B.R., Eds., Veterinary Cancer Medicine, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia.

- Nielsen, S.W. and Kennedy, P.C. (1990) Tumors of the Genital System. In: Moulton, J.E., Ed., Tumors in Domestic Animals, 3th Edition, University of California Press, Los Angeles, 498-501.

- Kennedy, P.C. and Miller, R.B. (1993) The Female Genital System. In: Jubb, K.V.F., Kennedy, P.C. and Palmer, N., Eds., Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th Edition, Academic Press, California, 451-452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-391607-5.50012-1

- Santiago-Flores, M.L., Jaro, M.C., Recuenco, F.C., Reyes, M.F. and Amparo, M.R.G. (2012) Clinical Profile of Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor Cases. Philippine Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, 38, 63-72.

- Varaschin, M.S., Wouters, F., Bernins, V.M.O., Soares, T.M.P., Tokura, V.N. and Dias, M.P.L.L. (2006) Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor in the Region of Alfenas, Minas Gerais: Clinicopathologic Forms of Presentation. Clínica Veterinária, 6, 332-338.

- Wellman, M.L. (1990) The Cytological Diagnosis of Neoplasia. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 20, 919-938.

- Boscos, C.M., Tontis, D.K. and Samartzi, F.C. (1999) Cutaneous Involvement of TVT in Dogs: A Report of Two Cases. Canine Practice, 24, 6-11.

- Murgia, C., Pritchard, J.K., Kim, S.Y., Fassati, A. and Weiss, R.A. (2006) Clonal Origin and Evolution of a Transmissible Cancer. Cell, 126, 477-487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.051

- Bassani-Silva, S., Sforcin, J.M., Amaral, A.S., Gaspar, L.F.J. and Rocha, N.S. (2007) Própolis Effect in Vitro on Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor. Revista Portuguesa de Ciências Veterinárias, 102, 261-265.

- Gaspar, L.F., Amaral, A.S., Bassani-Silva, S. and Rocha, N.R. (2009) Immunoreactivity to P-Glycoprotein in the Different Cytomorphological Types of Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor. Veterinaria em Foco, 6, 140-146.

- Moore, A.S., Leveille, C.R., Reimann, K.A., Shu, H. and Arias, I.M. (1995) The Expression of P-Glycoprotein in Canine Lymphoma and Its Association with Multidrug Resistance. Cancer Investigati-

on, 13, 475-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07357909509024910 - Baldini, N., Scotlandi, K., Barbanti-Bròdano, G., Manara, M.C., Maurici, D., Bacci, G., Bertoni, F., Picci, P., Sottili, S., Campanacci, M. and Serra, M. (1995) Expression of P-Glycoprotein in High-Grade Osteosarcomas in Relation to Clinical Outcome. New England Journal of Medicine, 333, 1380-1384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199511233332103

- Ginn, P.E. (1996) Immunohistochemical Detection of P-Glycoprotein in Formalin-Fixed and Paraffin-Embedded Normal and Neoplastic Canine Tissues. Veterinary Pathology, 33, 533-541.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030098589603300508

NOTES

*Corresponding author.