Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.09 No.08(2019), Article ID:94474,20 pages

10.4236/ojn.2019.98063

Effect of INTERACT on Promoting Nursing Staff’s Self-Efficacy Leading to a Reduction of Rehospitalizations from Short-Stay Care

Carmen U. Potter

Chamberlain University, Chamberlain College of Nursing, St. Louis, USA

Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: June 7, 2019; Accepted: August 18, 2019; Published: August 21, 2019

ABSTRACT

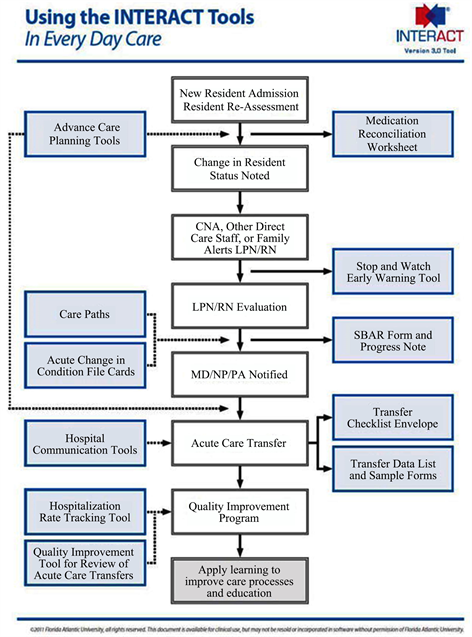

One in four clients discharged from an acute care facility to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) required readmission to the hospital within 30 days. Neuman, Wirtalla & Werner believe that two-third of those readmissions are avoidable. Reducing the frequency of rehospitalization from short-stay care is essential for two primary reasons: 1) Clients are exposed to hospital-acquired infections that lead to increased comorbidities, and 2) potentially avoidable hospitalization will decrease the amount of funding distributed by Medicare. The setting for the proposed change initiative was a for-profit, nondenominational SNF in Missouri. Of the 120 beds, 16 were devoted to short-stay care. The convenience sample included four registered nurses and eight licensed practical nurses who had agreed to participate in the pilot. The purposive sample included short-stay clients. Interventions implemented at the pilot skilled nursing facility are components of the validated INTERACT quality improvement program. INTERACT (Appendix A) is comprised of several tools designed to assist and guide front-line staff in early identification, assessment, communication, and documentation about acute changes in client condition. Measured results examined the effectiveness of the proposed intervention. The outcome being assessed in the project was the number of avoidable hospital admissions after implementation of the INTERACT quality initiative tools. The long-term objective for the pilot was a 2% decrease in client rehospitalizations from the short-care unit during the eight weeks of practice implementation. The clinical question for the proposed practicum project was, “For the nursing staff on a short-term rehab unit, does the implementation of an evidence-based patient evaluation tool, INTERACT lead to a reduction in avoidable hospital admissions?”.

Keywords:

Rehospitalization, INTERACT, Nursing Home, Quality Improvement

1. Introduction

Reducing hospital-acquired conditions and decreasing the number of avoidable rehospitalization are targeted goals of federal health care reform. Vulnerable populations being cared for in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) are often subjected to unnecessary emergency room visits and rehospitalizations. Not only do these actions play a part in healthcare costs inflation, hospital-acquired complications and increased morbidity and mortality rates occur because of avoidable visits to an acute care facility. According to Ouslander, Bonner, Herndon, and Shutes, Medicare and Medicaid may save billions of dollars if unnecessary hospital admissions decrease over the next several years (2014) [1].

Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfer (INTERACT) is a quality initiative implemented by many skilled nursing facilities in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Singapore. Consistent use of the program has been associated with a 24% reduction in rehospitalizations of nursing home clients over a six-month period [1] [2]. The purpose of the proposed clinical practice change process was to determine if implementing components of the INTERACT program at the SNF would reduce unnecessary rehospitalizations of clients from the short-stay care unit. The project proposal provides an overview of how INTERACT is used to successfully decrease unessential rehospitalizations. Information on the significance of the problem as it relates to a higher than the national percentage of rehospitalizations associated with not using a quality program such as INTERACT is presented. Practice recommendations and the plan to implement the proposed change process are discussed with the goal being preventing unnecessary hospitalizations when safe to do so [3].

2. Significance of the Practice Problem

A needs assessment was conducted at the skilled nursing facility. The administration reported the facility has a higher percentage of rehospitalizations from short-care stay than the national average: 26.7% compared to 21.1% nationally (Figure 1). Knowing that distribution of funds by Medicare is determined by the facility’s rehospitalization rate and level of improvement, the skilled nursing facility’s leaders sought a quality change process that will decrease the percentage of hospitalizations. Leadership focused on reducing unnecessary rehospitalizations from short-stay care for primarily two reasons: 1) Clients are exposed to hospital-acquired infections that lead to increased comorbidities, and, 2) avoidable rehospitalizations will decrease the amount of funding distributed by Medicare.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued the final rule for

Figure 1. Percentage of short-stay care clients rehospitalized after a nursing home admission (2015).

2016 Medicare skilled nursing facility payment rates. Components of the final rule includes value-based purchasing (VBP) provisions for skilled nursing facilities, based on a hospital readmission measure, set out the 30-day SNF all-cause/all-condition hospital readmission measure and adopt that measure for the new SNF value-based purchasing program.

The VBP plans established a 2% withhold to SNF Part A payments that can be partially earned back based on a SNF’s rehospitalization rate and level of improvement. This measure is claim-based, requiring no additional data collection or submission burden for SNFs. The measure is based on 12 months of data compiled by CMS [4].

Researchers that study avoidable hospitalizations among the nursing home population use various definitions and conditions that are potentially avoidable and could be treated at the skilled nursing facility. This is feasible if the nursing staff is skilled in providing care and conduct reliable and accurate assessments. Polniaszek, Walsh & Weiner [5] prepared a report for the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services discussing the background and options related to hospitalizations of nursing home clients.

Avoidable hospitalizations are generally grouped into three clinical categories. Preventable but requiring hospitalization, once it occurs, is related to a condition that may not have transpired if high-quality care had been provided by nursing staff and other healthcare providers. It usually leads to hospitalization. An example is the septic resident. Sepsis often occurs when nursing staff do not recognize an infection before it worsens. Septic patients should always be transferred to the hospital for life-threatening conditions.

A second category is preventable but discretionary hospitalization once it occurs. Skilled nurses supported by available and competent healthcare providers sometimes manage conditions at the skilled nursing facility. The condition may have been preventable or may have developed despite high-quality care. Pneumonia is the most common indicator associated with potentially avoidable hospitalization.

The third category of avoidable hospitalization is futile care. For the client near the end of life, futile care neither improves or prolongs quality of life. It is essential that advance care documents be in place. It is of equal importance for family members and staff have a clear understanding of the intent of such documents for the client near end of life to avoid an unnecessary hospitalization [5].

Reducing avoidable rehospitalizations of nursing home clients is a priority area of interest addressed by the CMS. Primary concerns of CMS are the quality of care for nursing home clients and costs perspectives associated with unnecessary rehospitalizations [6] [7]. In some cases, rehospitalization rates were higher for nursing home clients than the geriatric population in the community. Approximately $972 million was spent on avoidable rehospitalizations from skilled nursing facilities in New York alone [6].

Skilled nursing facilities are facing financial penalties for unnecessary rehospitalizations of Medicare clients. Facility leadership will need to reevaluate their ability to provide safe quality care to clients with complex needs [8]. Determining needs for additional training of nursing staff is essential for staff to care for the frailer client with comorbidities. Along with this, leadership of the skilled nursing facilities will need to avoid accepting clients with physical and mental needs the nursing staff is not familiar with until training and education are provided. There are many factors and incentives that influence the decision to hospitalize long-term care clients that are considered by nursing staff (Figure 2) when making the decision to transfer the client to the hospital [3].

Lamb, Tappen, Diaz, Herndon & Ouslander conducted a mixed method qualitative and quantitative study of skilled nursing facilities nursing staffs’ understandings of avoidable hospital transfers [9]. The staff had implemented INTERACT as a quality improvement. After the completion of the pilot, nursing staff rated 76% of the transfers were not avoidable. Cited reasons included acute condition change in the client, family insistence, and order for transfer from the healthcare provider. Nursing staff pointed out these same reasons as causes for avoidable rehospitalizations [9].

Policies in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have created financial rewards to skilled nursing facilities which are able to provide appropriate care to the client who develops acute changes in condition without transferring to the hospital [2]. CMS has identified six condition categories that contribute approximately 80% of avoidable hospitalizations [4] :

· Pneumonia

· Dehydration

· Congestive heart failure

· Urinary tract infection

· Skin ulcers, cellulitis, and

· Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma

Figure 2. Factors and incentives that influence the decision to hospitalize long-term care patients [3].

This is not to say nursing staff should avoid rehospitalization of all clients. Such decisions may result in unintended outcomes such as deterioration in condition leading to death [9]. Skilled nursing facility staff have to demonstrate above average assessment skills to prevent unnecessary rehospitalizations. Nursing staff must perform ongoing assessments with appropriate communication of the assessment findings to healthcare providers as acute changes of clients are discovered. Assessments and dissemination of the findings to the healthcare provider must be performed professionally with the use of validated tools.

The ACA requires CMS to establish regulations for quality assurance performance improvement (QAPI) for skilled nursing facilities. Section 6102 of the Affordable Care Act also requires CMS to provide “technical assistance, tools and resources for providers promulgating the new regulation” [1]. INTERACT may provide skilled nursing facilities a way to reduce hospital readmissions that are not necessary. Three general characteristics have been noted in facilities that implemented INTERACT successfully: leadership support, engagement of nursing staff and a site champion, and a culture enthusiastic about quality improvement [1].

Improperly trained nursing staff can lead to negative client outcomes resulting from unnecessary rehospitalizations. More than 2 million skilled nursing facility clients are transferred to the emergency room, and almost half are hospitalized. Rehospitalizations interfere with client-established relationships and care patterns at the skilled nursing facility. Added risks include the occurrence of adverse events, such as falls, skin ulcers, and hospital-acquired infections [2].

Another problem resulting from unnecessary rehospitalizations is undesirable financial consequences as well as sanctions by the regulatory agency. Decisions that are driven by reimbursement rates and regulatory policies often override client and family preferences. Complying with CMS regulation and still maintain expected profits are areas of importance to corporate stakeholders. This could present a barrier in the adoption of new validated strategies that can be implemented to reduce avoidable rehospitalizations [2] [8].

3. Theoretical Frameworks

McEwen identified Benner’s Model of Skill Acquisition in nursing as helpful as it defines the importance of retaining and rewarding clinical expertise in practice settings [10]. Using Benner’s Model as a conceptual framework, continued studies have been done to determine the achievement of the nurse in decision-making skills. It is also common to utilize Benner’s applicability in the development of procedures and protocols for orientations of new nurses and new graduates [10]. Benner’s primary philosophical argument is that skill achievements are quicker and safer when experience-based and the nurse has a firm educational foundation. Nursing skills and application of those skills allow the nurse to focus on establishing skilled nursing interventions within the scope of practice while using effective critical thinking skills within the practice setting [11].

Benner’s model explains that as a nurse advances through the levels of novice to expert, changes are mirrored in three aspects of skill performance. One, the individual shifts from depending on abstract principles to the use of past concrete experiences. Secondly, there is a change in the learner’s outlook of the situation, where it is seen less as distinct equal pieces and more as a whole where only certain parts are significant. Lastly, the individual changes from an outside observer of the situation to an engaged performer [12].

Novice or beginner nurses are not able to practice safely related to lack of experience in the area they are expected to perform. They lack experience, knowledge, and training and are not able to conduct a high-quality condition assessment. Novice nurses do not communicate client information in an effective manner to the healthcare provider [11].

Advanced beginner nurses are developing knowledge. They continue to require support as they begin to assess clients safely and effectively. Advanced beginner nurses still take cues from the more experienced nurse [13].

Competent nurses demonstrate efficiency and are confident in their abilities to provide safe care to the client. Competent nurses have been on the job 2 - 3 years. Problem solving becomes easier and appropriate decisions are made in the client’s best interests [13].

The proficient nurse provides holistic care and has learned from previous experiences. Proficient nurses establish care priorities and manage time well. They have developed intuition and demonstrate deep understanding of wholeness. They are analytical and provide high-quality safe client care [13].

According to Alligood, Benner describes clinical nursing practice by using an interpretive phenomenological approach [14]. Dr. Benner maintains that there are excellence and power in clinical nursing practice that can be visible through articulation research. In addition, Benner defines skill and skilled practice to mean implementing skilled nursing interventions and clinical judgment skills in actual clinical situation [11] [15]. Skilled activities are often thought of as less than intellectual but these activities are dependent on embodied knowing. Benner believes that competency assessment should be established in actual practice, under pressure, and over time, and related to patient outcomes [11]. Benner’s philosophy easily provides the framework for a hospital-based quality improvement innovation study.

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Model of Evidence-based Healthcare (Figure 3) provides a framework for evidence-based practice (EBP) set in healthcare evidence. The model defines EBP as “clinical decision-making that considers the best available evidence; the context in which the care is delivered; client preferences; and the professional judgment of the health professional” [16]. The JBI model conceptualizes the process of improving health outcomes through the understanding and translation of knowledge into the clinical arena. The center of the JBI model focuses on feasibility of the proposed intervention, appropriateness of the intervention to the situation, meaningfulness to the group providing them with a positive experience, and effectiveness of the intervention in achieving the desired outcomes [16].

The model acknowledges that innovative and new information occurs with both primary and secondary research. Systematic reviews are essential to identify knowledge gaps in clinical practice. Research does not always exist for every intervention or process. Healthcare providers and other clinicians must still make care decisions and continue searching for evidence to generate safe decision-making.

Evidence implementation is a purposeful set of activities developed to engage key stakeholders. Presenting research evidence to decision makers is conducive to sustain ability of quality improvements [16].

Figure 3. Joanna briggs institute model of evidence-based healthcare.

4. Synthesis of Literature

A literature search was conducted using key terms “rehospitalization, nursing home, INTERACT, and quality improvement”. Papers published from 2009 to 2016 were included and served as the foundation in establishing whether the use of structured tools in the skilled nursing facility reduced potentially preventable hospitalizations. Of the 61 articles located, 14 were specific to the area of interest. Levels of evidence were assigned to each study. The synthesis of literature includes nine systematic reviews/meta-analysis and five primary research studies. Integrative/summary articles are not included in the synthesis. It was determined that available evidence recommends training of nursing home staff and structured tools used consistently use may decrease unnecessary hospital admissions from skilled nursing facilities. Research also suggests barriers such as lack of enthusiasm or support for the change initiative may threaten validity and reliability of data collection. Nine of the fourteen peer-reviewed journal articles are systematic reviews. One is a randomized control study that targets the use of standardized validated tools such as the ones available in the INTERACT quality initiative program. All articles conclude that education and training are needed to manage clients’ deteriorating conditions. Secondly, communication problems between the skill nursing facility staff and healthcare providers must be resolved to avoid unnecessary rehospitalizations. The authors also agree further research is needed. Generally, most authors agree that determining gaps between local practice and best (evidence-base) practices is the first step toward reducing readmissions (Appendix B).

The remaining five articles are pilot studies conducted at skilled nursing facilities. All studies used INTERACT as a strategy to reduce client hospital readmissions. Education and nursing staff support were common themes identified (Appendix C). Staff confidence is essential for a quality initiative program to be successful. INTERACT tools can play an important role in assisting skilled nursing facilities to improve quality of care and contribute to CMS efforts to reduce morbidity and costs associated with rehospitalization. However, a need is indicated for further evaluation of INTERACT interventions in more controlled trials. They are needed to provide more reliable evidence to skilled nursing facility leadership and therefore promote a better understanding of such strategies.

The literature synthesis revealed similar conclusions from both systematic and pilot research studies. Formal educational activities and consistency in practice influence rehospitalization rates from skilled nursing facilities. “Such readmissions cost the U.S. healthcare system approximately $17 billion annually” [17].

5. Methods and Data

The setting for the proposed practice change was a for-profit corporation, non-denominational skilled nursing facility located in Missouri, United States. The capacity of the SNF was 120 beds of which 16 were devoted to short-stay care. The convenience sample consisted of four registered nurses (RNs) and eight licensed practical nurses (LPNs) who had agreed to participate in the pilot and worked varying shifts. The purposive sample for data collection included short-stay care clients at the skilled nursing facility. Protection of human rights was maintained throughout the project.

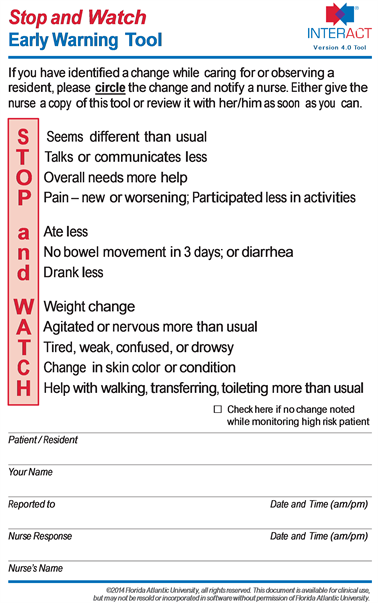

The interventions implemented at the skilled nursing facility were components of INTERACT. INTERACT decision support tools included Stop and Watch lanyard cards (Appendix D) Care Paths, Acute Change in Condition file cards (Appendix E), Change in Condition Progress Note, and SBAR Communication Tool. The Director of Nursing wanted to acclimate the nursing staff slowly to INTERACT components to facilitate more of a buy-in from the nurses.

Comparison of pre- and post-hospitalizations from short-care stay was conducted after implementation of the INTERACT program. There was no standardized method in place to assist nursing staff with client evaluation or in giving the condition information to the healthcare provider. The comparison for this project was pre- and post-intervention data collected from CMS. The nurse manager reported that a standardized evaluation and handoff tool was not used by nursing staff and has led to high percentages of hospitalizations from the short-care unit. The evaluation instruments for this project also consisted of pre-and post-implementation survey 11 item 5-point Likert-type scale where five indicated the participant strongly agreed and one indicated strongly disagree. This formative tool was used to establish participants’ confidence in knowledge of INTERACT and their confidence in recognizing changes in the client condition. The summative evaluation instrument was the same survey and data analysis. The SPSS program was utilized for data analysis. A paired t-test was applied to evaluate rehospitalizations pre- and post-implementation of INTERACT using the Acute Care Transfer Log worksheet.

The assessed outcome was the number of avoidable hospital admissions after implementation of the INTERACT quality initiative components. The long-term objective for the pilot was a 2% decrease in client re-hospitalizations from the short-care unit during the eight weeks of practice implementation.

6. Analysis and Results

The effect on a number of rehospitalizations over three periods: the mean rate of rehospitalizations at the end of November 2016 was 66%, during February and March 2017 was 16% (pre-implementation), and during April and May 2017 was 60.5% (post-implementation) (Figure 4). Agency management explained that some of the differences among the three rates are the differences in acuity of residents and in family preferences for the residents. Client care acuity was considerably lower in February and May 2017. Results indicated at least a 5.5% reduction in rehospitalizations was achieved from November 2016 compared to April May 2017 when client acuity levels were higher.

Twelve licensed nursing personnel participated in both phases of the project with four registered nurses and eight licensed practical nurses. Based on data, there were no statistically significant differences on any of the items used to evaluate the INTERACT program.

Although there were no statistically significant differences, there were increases in the mean scores on the items related to Table 1.

Figure 4. Effect of INTERACT on rehospitalizations.

Table 1. T test results for each item and total score on instrument used to evaluate the interact program.

· Confidence in Reporting Changes,

· Comfortable Knowing What to Do,

· Comfortable Prioritizing Needs,

· Ability to Recognize Changes,

· Realistic Job Expectations,

· Satisfaction with Responsibility, and INTERACT Was Helpful as well as the total mean score on the instrument, and,

· INTERACT Was Helpful as well as the total mean score on the instrument.

The only items where there was a decrease in mean score were: Can Use Knowledge to Prevent Harm and New Processes Supported by Management. There was no change in mean scores on two items: Confident Communicating Conditions and Comfortable Suggesting Changes.

Two things are well known in writing about survey items. One is social desirability answers: it is difficult to reveal weaknesses. Secondly, there is the response set bias where participants put one answer for all items without reading. The statistician believed the first is more likely with this survey since some items required reverse scoring.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

Current literature supports the need for the proposed project for evaluation a quality initiative to implement all or some of the INTERACT tools and strategies for decreasing potentially unnecessary hospital transfers for nursing home clients. Consistent and structured communication improves nursing staff’s ability to observe, report, act, and communicate information appropriately to the healthcare provider to avoid hospitalization [3]. The search of literature also revealed that specific chronic disease processes such as pneumonia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and congestive heart failure often result in potentially avoidable hospital admissions [3]. Evidence does support implementation of tools and strategies to communicate in a structured manner using a tool such as SBAR to achieve beneficial results [18].

The significance of the problem of higher than state and national percentages as it relates to client transfers to hospitals is related to a nonstandardized process. Validated tools available from the INTERACT quality initiative program may reduce avoidable rehospitalizations from skilled nursing facilities. Establishing and consistent use of a standardized set of tools at the practicum facility may improve quality of care, reduce avoidable hospitalization CMS scores, and decrease client exposure to hospital-acquired infections. An improvement in the reduction of rehospitalizations scores determines reimbursement rate for skilled nursing facility payments as provision set by the Affordable Care Act. Implementation of the INTERACT program that is in the practicum facility will meet the needs and requirements of the facility’s leadership as well as nursing staff at the microlevel of the organization.

INTERACT is a validated quality improvement program that provides structured information and tools that may be used for client assessment that can be relayed to the healthcare provider in a structured SBAR format. The INTERACT quality improvement program is designed to assist front-line staff in early identification, assessment, communication, and documentation acute changes in client condition. Components include clinical and educational tools and strategies for use in everyday practice in skilled nursing facilities. Skilled nursing facilities across the country have implemented the INTERACT quality improvement program. Many facilities have significantly reduced avoidable hospitalizations using these resources [1] [2].

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my great appreciation to Martha A. Spies, Ph.D., MSN, RN for her valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this clinical research work. My grateful thanks are also extended to Dr. Spies for compiling data and interpreting statistics for the project. Her willingness to give her time so generously is deeply appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

Potter, C.U. (2019) Effect of INTERACT on Promoting Nursing Staff’s Self-Efficacy Leading to a Reduction of Rehospitalizations from Short-Stay Care. Open Journal of Nursing, 9, 835-854. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2019.98063

References

- 1. Ouslander, J., Bonner, A., Herndon, L. and Shutes, J. (2014) The Interact Quality Improvement Program: An Overview for Medical Directors and Primary Care Clinicians in Long-Term Care. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 15, 162-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005

- 2. Toles, M., Young, H.M. and Ouslander, J. (2012) Improving Care Transitions in Nursing Homes. Generations, 36, 78-85.

- 3. Maslow, K. and Ouslander, J. (2012) Measurement of Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations. http://www.ltqa.org/wp-content/themes/ltqaMain/custom/images/PreventableHospitalizations_021512_2.pdf

- 4. Boccuti, C. and Casillas, G. (2017) Aiming for Fewer Hospital U-Turns: The Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Fewer-Hospital-U-turns-The-Medicare-Hospital-Readmission-Reduction-Program

- 5. Polniaszek, S., Walsh, E. and Weiner, J. (2011) Hospitalizations of Nursing Home. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/76296/NHResHosp.pdf

- 6. O’Neil, B., Parkinson, L., Dwyer, T. and Reid-Searl, K. (2015) Nursing Home Nurses’ Perceptions of Emergency Transfers from Nursing Homes to Hospital: A Review of Qualitative Studies Using Systematic Methods. Geriatric Nursing, 36, 423-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.06.001

- 7. Rantz, M., Flesner, M., Franklin, J., Galambos, C., Pudlowski, J., Pritchett, A., Alexander, A. and Lueckenotte, A. (2015) Better Care, Better Quality. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 30, 290-297. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000145

- 8. Feldkamp, J. (2014) Push to Avoid Rehospitalization Has Unintended Outcomes. Caring for the Ages, 15, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carage.2014.08.010

- 9. Lamb, G., Tappen, R., Diaz, S., Herndon, L. and Ouslander, J. (2011) Avoidability of Hospital Transfers of Nursing Home Residents: Perspectives of Frontline Staff. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 59, 1665-1672. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03556.x

- 10. McEwen, M. (2011) Theoretical Basis for Nursing. 3rd Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- 11. Benner, P. (2001) From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice, Commemorative Edition. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- 12. Benner, P. (1984) From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park, 13-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-198412000-00025 http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/nursing/projects/Documents/novice-expert-benner.pdf

- 13. Alligood, M. (2014) Nursing Theorists and Their Work. 8th Edition, Mosby, St. Louis.

- 14. Brkczynski, K. (2014) Nursing Theorists and Their Work. 8th Edition, Mosby, St. Louis.

- 15. Jordan, Z., Lockwood, C., Munn, Z. and Aromataris, E. (2019) The Updated Joanna Briggs Institute of Evidence-Based Healthcare. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 17, 58-71. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000155

- 16. Nelson, J. and Pulley, A. (2015) Transitional Care Can Reduce Hospital Readmissions. American Nurse Today, 10. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844301

- 17. Ouslander, J., Lamb, G., Tappen, R., Herndon, L., Diaz, S., Roos, B., Grabowski, D.C. and Bonner, A. (2011) Interventions to Reduce Hospitalizations from Nursing Homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II Collaborative Quality Improvement Project. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 59, 745-753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03333.x

- 18. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (2015) Skilled Nursing Facility Readmission Measure (SNFRM) NQF #2510. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Other-VBPs/Technical-Report-Supplement.pdf

Appendix A. INTERACT

Appendix B. Systematic Reviews

Appendix C. Summary of Primary Research Evidence

Appendix D. INTERACT Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool

Appendix E. INTERACT Change of Condition Card Sample