Open Journal of Nursing, 2013, 3, 404-413 OJN http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.35055 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojn/) Cultural models of female breasts and breast cancer among Korean women Eunyoung E. Suh Seoul National University College of Nursing and Research Institute of Nursing Science, Seoul, South Korea Email: esuh@snu.ac.kr Received 9 August 2013; revised 1 September 2013; accepted 10 September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Eunyoung E. Suh. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Although a great many qualitative descriptions of the experience of having breast cancer exist, they over- whelmingly represent experiences of women in West- ern cultures and are based on assumptions that stem from Western individualism. This study explores and describes cultural models shared by a group of non-Western women, South Koreans, in reference to female breasts and breast cancer. The hermeneutic phenomenology-grounded qualitative study was conducted with 40 Korean women, between 23 and 81 years of age, half of whom were breast cancer sur- vivors. The analysis elicited two cultural models, both characterized in terms of physical relationships to others (as opposed to the woman’s individual or in- dependent view of her body): a breast-feeding mother to a child and an attrac ti ve w ife to a husband. Female breasts are interpreted as a medium that connects women to roles as mothers and wives. Breast cancer can lead women to detach from their previous rela- tional and role-oriented identities. Cultural traditions, cultural concepts, and culture-related health beliefs in Korea are interwoven deeply in the women’s sto- ries about breasts, as a gendered organ, and its dis- ease. The findings suggest that understanding in- digenous cultural models should precede any suppor- tive breast cancer care for women from non-Western cultural backgrounds. Keywords: Breast Cancer; Cultural; Korean; Qualitative; Phenomenology 1. INTRODUCTION Cultural models are defined as the shared perspectives or cognitive schemas through which members of a par- ticular culture understand and interpret their realities [1]. People who share identical cultural models tend to con- struct their realities and interpret them in similar ways. Illuminating and deciphering cultural models thus offers a profound understanding of human motives and be- haviors [2,3]. Breast cancer, as the most common female cancer, is estimated to affect over 1.38 million women according to the 2008 GLOBOCAN of the World Health Or- ganization [4]. As the incidence and survivability of breast cancer have increased, so has the number of survivors, which exacerbates its profound ramifications in women’s lives [5-12]. Women’s lives are described as “being in suspense” [13] and “scattered into an unforeseen swirl” [14] when they are told that they have breast cancer. Women feel that their previous routines have been greatly changed [7,15] and experience phy- sical and emotional turmoil as they undergo cancer treatments such as mass excision surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy [16-18]. Even after cancer treatment, a woman must deal with the fact that her symbol of womanhood is deformed or removed [19,20] and her sexuality may have changed due to chemotherapy and hormonal treatment [21-23]. Despite the ordeal of the illness trajectory, women live out their lives with breast cancer by being “against all odds” [7], finding meaning in their experiences [6], and looking for spiritual equilibrium [24,25]. In addition, women interpret and reconstruct their experiences of breast cancer as positive drivers of personal growth [26] or as opportunities for enlightenment and transference [5,11,12]. A meta-synthesis of 30 qualitative research reports of women’s lives with breast cancer focused on the impact of breast cancer on “self” [27]. Through the experiences of breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment, women obtained an “awareness of their own mortality”, lived with “an uncertain certainty”, validated attached relationships around them, and ultimately redefined themselves [27]. Although great numbers of qualitative descriptions of women’s lives with breast cancer exist, they mainly OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 405 represent experiences of women in Western cultures [28] and most assumptions of the reports stem from Western individualism. The physical deformation due to the surgery is often regarded as the changes in body image and sexuality at an individual level [19,29]. The meanings of the experience of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment are also often analysed in a link of “self” [27] or within the individual context [30]. Unlike an experience that is valued and interpreted based on each individual’s reference points in individualistic culture, a person in a collectivistic culture will often define herself as a part of her group, and holds a view of “self” according to the norms and traditions of that group [31]. Therefore, cultural models of female breasts and breast cancer of women in non-individualistic cultures may differ from those of Western cultures. Some reports of the significance of female breasts and the experiences of breast cancer for women in non- Western cultures provide a glimpse of the need for a deeper examination of cultural models among those wo- men. No Korean-American women used words related to “body image” or “sexuality” when asked to express their symbolic meanings for female breasts and breast cancer, according to the cited excerpts [32]. Arab-American women did not express concerns of “altered body image” or “loss of their body part” when relating their ex- periences with breast cancer. Instead, they spoke of breast cancer as “fate” and of their priorities and value of their roles in the family [33]. The importance of religion, the beliefs of fatalism, and the significance of their families and the completion of women’s roles in the family were found in the reports with women from Arab [33], Chinese [34], Pakistani [35,36], South Korean [32, 37], and Hong Kong Chinese families [15]. This study therefore explored and aimed to describe cultural models shared by a group of non-Western women, South Kor- eans, in regard to female breasts and breast cancer. Such descriptions are expected to expand the understanding of how meanings and interpretations of certain experiences are shaped by cultural models or cognitive schema. 2. METHODOLOGICAL BASIS This qualitative study was philosophically inspired by hermeneutic phenomenology from Heidegger, Gadamer, and Ricoeur [38]. In their hermeneutic phenomenology, the understanding of a person or an individual’s behavior occurs in the context of the world that the person lives in (“being-in-the-world”); truth is temporally determined in accordance with the historical and cultural context of the present knowledge [39]. Especially (according to Gadamer and Ricoeur), text, as an object of interpretive analysis, is not only a written document, but also a meaningful action that opens up the existential world of the nature of human experience, thus permits textual multiplicity and textual plurality [39,40]. This study also followed American phenomenological methodology, in which descriptions of participants’ “situated” experi- ences are themselves weighted [41]. Understanding and explanation of their cultural model were articulated here through the researcher’s engagement and interpretation of interview transcripts [39,40]. 2.1. Participants In this qualitative study, interviews with 40 Korean women, including twenty breast cancer survivors and twenty healthy women, were analyzed and interpreted. The interviews with healthy Korean women were adapted from a larger grounded-theory study on breast cancer screening behaviors among Korean immigrant women [42]. The interviews with breast cancer sur- vivors were conducted based on the tentative analysis of the earlier interviews with healthy women to expand the horizons of the phenomena under investigation. Par- ticipants with histories of breast cancer were the subjects of a completed intervention study [43]; they joined in this qualitative study based on their interest in par- ticipation. Participants’ ages ranged from 23 to 81 years. They were mostly married and educated beyond high school (Table 1). Women who reported their socio- economic status as middle comprised more than half of the participants. Only two of the healthy women and six of the breast cancer survivors denied any religious beliefs. All women with breast cancer had histories of mass removal surgery, and all but two received chemotherapy along with the surgery (Table 1). 2.2. Procedures The institutional review board (IRB) of the university where the researcher was affiliated approved the study. Korean women were approached and recruited using a theoretical and convenient sampling technique. Healthy Korean women were recruited through Korean com- munity churches and social groups in Philadelphia, USA, and breast cancer survivors through a university cancer center in Seoul, Korea. The possible influences of the geographical and time-point differences in data collection between the healthy women and the breast cancer survivors were taken into account in the interpretive analysis. Upon agreeing to participate in the study, each subject joined in an individual interview with the researcher in a quiet and comfortable place that the participant chose, such as at their home, a restaurant, or a meeting room in a cancer center. Although it was called an “interview,” the data collection proceeded through conversation between each participant and the researcher, rather than just asking questions of the participants, to refrain from creating a hierarchical relationship [44]. The semi- constructed questionnaires provided the contents and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 406 Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study participants. Healthy Women (n = 20) Breast Cancer Survivors (n = 20) Age Range (Mean) 23 - 81 (47.75) 26 - 63 (45.55) Married 12 16 Marital Status Not Married 8 4 ≤Middle School 5 2 High-School 4 4 Education ≥College 11 14 High 3 2 Middle 12 14 Scioeconomic Status Low 5 4 Yes 18 14 Religion No 2 6 Yes - 20 Surgery No - 0 Yes - 18 Chemotherapy No - 2 directions of the conversation between the researcher and each participant. Those included: “what comes to your mind when you think of female breasts and breast cancer?”, “tell me any episode or memory you have in reference to female breasts and breast cancer,” “tell me any episode or story related to female breasts in your family norms, customs, social relations.” The breast cancer survivors were also asked: “tell me what it is like being diagnosed and living with breast cancer”, and “tell me any stories of how your life changed or situated by the ordeal of breast cancer”. The interviews lasted an hour to 2 hours in Korean until the participants expressed their completion of disclosure of their stories and thoughts on the given topics. All interviews were recorded on a digital voice recorder; all participants agreed to being recorded. 2.3. Data Analysis All recorded interviews, which were conducted in Ko- rean, were transcribed into verbatim transcripts. First level coding, in which meaningful words, expressions, or sentences are coded as units of analysis, was done in Korean in order not to lose any particular Korean ex- pressions or culturally coloured verbatim. Bilingual con- stant comparative translation between Korean and Eng- lish came from categorical/axial levels of coding [45]. The MAXQDA© software program for qualitative data analysis was used for data management and reorganiza- tion. Parts of the conversations were translated into Eng- lish by two bilingual translators to present as exemplars in this article. In Korean, the first person pronouns, “I” or “my”, are not used in conversation unless it is neces- sary to make meanings accurate, therefore, first person pronouns were added in the quoted excerpts with paren- thesis for sound English grammar. The transcribed data were read many times and in- terpreted by the researcher within the hermeneutic cir- cle in which the interpretive dialogue between text and the interpreter occurred and a “fusion of the horizons” was reconstructed [46]. Three practical strategies for interpretive analysis by Benner [47], thematic analysis, exemplars, and paradigm cases, were applied in the analysis. The thematic analysis was conducted through careful reading of the text, recognition of patterns, meanings, concepts in the text, and interpretation of in- formation and themes within the given cultural and his- torical context [48]. Several exemplars were selected to elucidate the truth value of the findings. The paradigm cases were explored and described to show how the meanings of female breasts and breast cancer for Korean women were constructed within their situational context [49,41]. To establish the rigor of this study focusing on credibility, transferability, and dependability, the deci- sion trail was created and audited by team members of a qualitative analysis group in which “events, influences, and actions of the researcher” were recorded [50]. 2.4. Ethical Consideration The participants were introduced to the study’s purpose and procedure upon their agreement to participate, and informed of their freedom to withdraw from the study anytime they wanted. All participants signed written consent forms to participate in the study and for voice recording. The recorded interviews were transcribed by professional transcriptionists who did not know the indi- vidual’s demographic profile. Any information in the transcripts traceable back to the individual was switched to anonymous symbols or pseudonyms by the researcher. 3. RESULTS The thematic analysis findings are presented synchro- nically according to the research topics although the participants told their stories to the researcher diach- ronically. The main theme elicited about female breasts was “relating one to one’s relational world”, whereas “detaching one from one’s usual world” was the main theme for breast cancer discussions (Table 2). These themes reflect participants’ way of perceiving their bodies and illnesses within a context of relationships. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 407 OPEN ACCESS Table 2. The cultural models of female breasts and breast cancer from a thematic analysis. Topics Main Themes Subthemes 1.1. Relating me to my roles for my husband and children 1.1.1. These connect me with my role as a mother of my children 1.1.2. These relate me to my role as my husband’s woman The Female Breasts 1. Relating one to one’s relational world 1.2. Taking the shared socioc ult ura l meanings for grante d 1.2.1. Not too big, not too small: the silhouette of the body 1.2.2. Covered, not get touched: the way of treating these Breast Cancer 2. Detaching one from one’s usual world 2.1. The aetiology: Against Sun-Li and forbearing Han inside 2.2. The experience: Unwanted engagement into an unfamiliar journey 2.3. The ramifications of breast cancer: Detaching me from my usual world Details about the major themes and subthemes are described with the quoted excerpts as exemplars; and a paradigm case is presented. 3.1. Relating One to One’s Relational World: Female Breasts In conversations with Korean women in this study, they mostly used the gender-neutral term meaning “chest” (Ga-Seum) to indicate female breasts. Other Korean words for either human female breasts, Yu-Bang (mean- ing “milk room”), or Jeot (mammal’s breasts or breast milk) were scarcely used. Every participant brought up either her husband or children first and talked about her roles for them, using female breasts as a medium. After the thorough description of their husbands and children, the participants turned the conversation to other various episodes and stories they had experienced in reference to female breasts, which reflected the sociocultural ways of seeing, mentioning, and treating female breasts among Korean people. 3.1.1. Relati ng Me to My Rol es for My Hu sband and Children The participants’ descriptions of female breasts were reconstructed and interpreted as connectors to their roles as mothers and wives. Women described female breasts as objects that related a woman to her roles as a spouse and as a mother of their children. One said, “They [fe- male breasts] make (me) think of man and baby. You provide milk to your baby to raise it. And you also use them for satisfying your man” (woman, age 35). (Words in parentheses were not spoken in Korean but added in the scripts for sound English grammar.) 1) These connect me to my role as mother of my children. Instead of directly articulating the word for female breasts, women often used the demonstrative pronoun, these, to indicate their breasts. Many participants for the first mentioned the image of breast feeding mother, the memories of breast feeding, and their roles of being a mother who breast fed their children. Breasts remind (me) of feeding and raising children. When (you) have a baby, (you) don’t care about shyness or anything. (You) just feed them anywhere. The feeling of connection with my babies when (I) fed them was so fantastic. It is beyond description (woman, age 36). Female breasts are for feeding children. Isn’t it a mother’s obligation to feed (her) kids? Besides that, (I) don’t have any thoughts about breasts (woman, age 77). 2) These relate me to my role as my husband’s woman. Following the schema of motherhood, the next pre- vailing theme of female breasts incorporated a woman’s role in relation to men, mostly to her husband, which was being sexually attractive to him. To the participants, breasts meant sexuality, which was recognized as part of her role. A 33-year-old, college-graduate, married woman told a story of how much she had struggled with her “not-sexy-as-before” breasts—not according to her point of view, but to her interpretation of her husband’s per- spective. (I was) never concerned about (my) breast size before I got married. But after (I) started breast-feeding our son, (my) breast shape changed. (It) is withered and sagged. (I) feel sad seeing (my) breasts in a mirror because this is not what a husband wants… A while ago, (I) asked (my) husband if (I could) get breast cosmetic surgery. He said (I) didn’t need to but I know he wanted (my) breasts to have a sexier shape. When we went shopping, how- ever, he is amazed by the pictures of sexy and voluptu- ous women in magazine display on the shelves. (He) looked at them carefully and said, “Wow, look at those breasts, what a good figure!” or “What a sexy woman (she) is!” (He) said (I) did not need to get cosmetic sur- gery on (my) breasts. But as a wife, (I) know (he) wants something sexier. (He) is just a man among other Ko- rean men, you know (woman, age 33). 3.1.2. Taking the Shared Sociocultur al Meanings for Granted As women incorporated their husbands’ perspective to  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 408 understanding and interpretation of their breasts in pre- vious descriptions, the participants also talked about various kinds of sociocultural symbolic meanings of female breasts in their everyday life. Especially in terms of size and shape, and the way of treating women’s breasts were told in detail reflecting the dominant social desires toward female breasts within Korean culture. 1) Not too big, not too small: The silhouette of the body Many participants shared stories about the size of breasts within a Korean sociocultural context. Inter- estingly, even if sexuality in relation to breasts pre- vailed in the participants’ perceptions, they preferred breasts to be not too big or too small in size. Me- dium-sized breasts created a socially appropriate “silhouette of the body”, embodying what they identi- fied as a sexy silhouette. Although sexiness was brought up in relation to their husbands, sexiness in this theme was rather an external symbolic view of woman in general than that of the sexual object of her husband. Breasts make a woman’s exterior. In these days, a man’s point of view is important for women. Breasts create a (woman’s) look and a sexy appearance (woman, age 20). In the old days, (girls) tied up (their) breasts in order not to be voluptuous. (We) were t oo shy to show our breast lines... (Girls) who had bigger breasts than average felt shy in those days… My friend has big breasts, so (sh e) bent (her) shoulder to hide them and wanted to show that (she) had normal size breasts. It was (her) handicap having bigger breasts than average (woman, ag e 60). Breasts remind (me) of (my) handicap. (My) breasts are so small, such that when (I) was a high school stu- dent, (I) was often embarrassed. (I) had a flat chest in my school uniform compared with my friends. (I) put some handkerchiefs in the bra to make (me) look good. When (I) was young, we didn’t have bras like (we) have now. That was kind of (my) handicap. As (you) know, Koreans value proper size of breast s . Not too big, no t too small (woman, age 54). 2) Covered, not get touched: The way of treating these With regard to the perception of their breasts, partici- pants often told stories referring the traditional treat- ments of breasts that they were taught. Evidently, the discourse related to the female breast had seldom been talked about in public, even in personal communications. In addition to a taboo about discussing female organs, breasts are supposed to be physically covered and se- cured, neither to be shown nor touched. The participants’ identification of their bodies was evidently influenced by the traditional notion of a chaste life for women in Ko- rean culture. When we were young, discipline for woman was hard. (I) don’t think (I) ever talked about my body or breasts with anyone. Especially, our mother strictly raised (her) children. (She) said, “Women should keep your body pure from men until you get married.” It was so strict. (woman, age 77). Even if a physician sees and touches (my) body as one of (their) patients, how (I) interpret it is different. Being touched and treated by someone who (I) don’t know well makes (me) feel uncomfortable. (I) would go for female doctors for (my) woman ’s exam. It is because that kind of touching by a man could contaminate (my) virginal purity (woman, age 23). In the old days, wom en’s breasts had to be covered, not shown…As our breasts grew in our teenage years, (my) mother taught (me) not to show anyone and keep (my) body untouched b y any man until I got married. So, (I) just thought it was the rule… not showing (my) body and not letting anyone touch (my) body (woman, age 81). 3.2. Detaching One from One’s Usual World: The Cultural Model of Breast Cancer According to participants’ descriptions, and similar to what would be expected from the cultural model of female breasts, breast cancer caused a change in inter- personal and sociocultural relationships. All partici- pants, including healthy women and breast cancer survivors, mentioned the deformation or mutilation of the breast and its effects in emotional, relational, and functional aspects under the context of relationships. For description purposes, the participants’ stories were reconstructed in terms of etiology, personal experiences, and ramifications of breast cancer. 3.2.1. Relati ng Me to My Rol es for My Hu sband and Children The participants’ beliefs about causes of breast cancer showed a distinctive feature incorporating traditional Korean health and illness beliefs, and a fatalistic per- spective derived from the culture. Most participants im- plied that life and critical life events were predetermined by providential power or by one’s Pal-Ja (fate), to which an individual should submit. Although they admitted that their predestined fates were to get ill with breast cancer, they presumed that either forbearing stresses or Han (heartburning) or opposing Sun-Li (universal principles) by disharmonizing with nature/others lead them to the illness. I think my having had too much stress caused my cancer… As (you) know, we often say that “forbearing Han inside causes disease” in our culture… For any Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 409 reason, accumulating stress and unresolved Han inside caused it. So when I got diagnosed with breast cancer, I cried and yelled at my husband that he caused it. He causes me to feel stressed all the time (woman, age 47). (I) think opposing natural principles caused my cancer. When I had my son, I tied up my breasts after (I) gave birth and got Yu-Jeot (a kind of breast inflammation). Drying up (my) breast milk instead of feeding, I guess, opposed the natural principles. Wh e n (I) manipulated natural rules against Sun-Li, it became problematic and eventually caused a cancer, (I) believe (woman , ag e 63). 3.2.2. The Experience: Unwanted Engagement into an Unfamiliar Journey The experiences of living with breast cancer were ex- pressed by the survivors. Not surprisingly, all breast cancer survivors had some kind of negative connotation with their experience. Sorrow, fear, extreme difficulty, suffering, unfamiliarity, and uncertainty emerged from the narratives. In addition, many participants articulated the experience as an unfamiliar journey, in which noth- ing is certain or definite, and which seemed to be an endless turmoil. Even 5 years after her treatment, one said the experience of the cancer ordeal was still vivid, and the fear of recurrence never diminished. From the point of time when I heard my diagnosis from my doctor, my whole world seemed to change. I feel like all fear, sorrow, and despair came into my fam- ily ever since, and the negative emotions and thoughts need to be intentionally moved out of me, or they are there forever. I feel like I began an endless, strange, and lonely journey by myself… a few steps with my fam- ily… but mostly by myself (woman , age 37). 3.2.3. The Ramifi cations of Breast Cancer: Detaching Me fr om My Usual World The breast cancer survivors’ perception of female breasts, as a medium of the relations with their loved ones, encourages both relational and social detachment through the experience of breast deformation. It altered their perceptions of their social roles of being mothers and wives, and disengaged them from the social norms of looking “normal” like other women. The survivor participants were concerned over the loss of their former roles, especially for their husbands. A woman’s percep- tion of the lost breast signifies that she is no longer able to fulfil her role as a sexual object of her husband. The participants brought up the silhouette caused by breast abscission. The participants’ point of view was external and they integrated “womanly” appearance into their perception, which was socially symbolized. When my hair started falling off [because of chemo- therapy], (my) husband and I cried together and we started using different rooms ever since. (I) wear a wig while he is home in order not to show him (my) bald head. (I) take off the wig only when (I) am by myself. The loss of my breast is irreversible, but the hairs will come back. (I) do not want to show (my) deficiency to my be- loved husband (woman, age 52). 3.3. Paradigm Case B.S. is a 37-year-old Korean woman with two children, aged 8 and 4. She met her husband in college and got married when she was 28. She recalled her married life had been busy raising kids, doing housekeeping, and fulfilling the roles as a wife and a daughter-in-law in her husband’s family. Being slender and weak since her youth, she felt exhausted by raising kids and doing all housekeeping by herself. She feels that she is always tired. She thought her life was as it should be because every woman lived a life similar to hers. As she has had sickness on and off due to her heavy household work, she ignored a lump in her left breast for a while; she thought to herself that it felt strange to have very low energy every day. When she heard about her breast cancer from her doctor, she was shocked and felt as if heaven had fallen down on her. Since then, everything has changed. She could not conduct her roles as a wife, a mother, and a daughter-in-law as much as she had previously. She thought that her internal stresses had finally burst out in the form of breast cancer. She resented her husband and others expecting too much of her all the time. The jour- ney of undertaking the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer was difficult, rather lonely, painful, unorganized, and uncertain. She felt that the entire cancer ordeal was hers alone, despite support from her husband and rela- tives. With a deformed breast and weakened body, B.S. feels that she does only half of what others (husband, kids, relatives, et al.) expect her to do. She feels de- tached from her previous self, her close family, and even from her husband. 4. DISCUSSION: INTERPRETIVE REFLECTIONS 4.1. Cultural and Contextual World the Women Live in Korean women, as with women in many Asian countries where women are in subservient positions, are raised with social and cultural dispositions of “what it means to be a woman in Korea”. The most dominant symbol of the ideal woman in Korea is the Hyeon-Mo-Yang-Cheo idealism that depicts a wise and sacrificial mother, and submissive wife [51,52]. The idea of Hyeon-Mo-Yang- Che originated from Confucian beliefs, which preordain and limit a woman’s identity to being a mother or wife at Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 410 home rather than being an individual [52-54]. This im- age is embedded in Korean cultural traditions, family institutions, and the educational system and moulds the image and social roles of Korean women. Along with the aforementioned symbolization of the Hyeon-Mo-Yang-Cheo, several Korean proverbs dis- tinctly reflect the traditions of valuing man over woman in ancient Korean culture. The two most common max- ims are the Nam-Jonn-Yeo-Bi (man is precious and re- spectful, women is vulgar and ignoble) and the Yeo-Pil- Jong-Bu (wife must be submissive and obedient to her husband) [51]. Unquestionably, women or associations with what is female or feminine are less valuable than men and what is seen as male. Female organs such as breasts or female genitalia are usually considered some- thing shameful, and need to be covered and secured [55,56]. From this point of view, it is not difficult to en- vision that maintaining breast health in this culture im- plies a complicated and distinct context. The images described by the participants reflect this Korean so- ciocultural context in which a woman is situated rela- tively normatively in a certain way, as it “should be”. 4.2. Living in the World with the Flow of Pure Principles and Predetermined Fate The word, Sun-Li, literally means “pure principles”. It implies that there are universal principles on which crea- tion must be based. The notion of Sun-Li originates from Confucian beliefs, in which proper ways (Jeong-Do) to be and to behave are considered natural [57]. Deviating from the pure principles causes disharmony, resulting in severe illnesses, such as breast cancer, according to the participants’ conversations. Participants also brought up their fate (Pal-Ja) often, referring one’s destiny or prede- termined ways of living. Pal-Ja literally means “eight characters”, which include a person’s time, date, month, and year of his or her birth [58]. According to Korean customs, a person’s date and time of birth are connected to universal principles and they reveal his or her fate. Participants believed in their predetermined fate; having ‘the life as it is’ is largely controlled by pure principles and individual predestined fate. 4.3. The Cultural Models of Female Breasts and Breast Cancer In Korean dialects, three words, Yu-Bang, Jeot, and Ga-Seum, indicate female breasts. Yu-Bang and Jeot generally refer to female breasts as opposed to Ga-Seum, which is a gender-neutral term meaning “chest”. The Korean terms, Yu-Bang and Jeot, which originate from the meaning of milk production, generally influences women’s perception of breasts. The word, Yu-Bang, is from Chinese: Yu means milk and Bang indicates a room or space. Typically, the Chinese character, Yu, consists of three parts, i.e., a hand, a son, and a flying swallow that is believed as a messenger to bless the son. Yu, picto- graphically implies handing a son blessed by a messen- ger. Thus, the word Yu-Bang imposes the meaning of a space for milk to raise a son. Although Yu-Bang is used as a scientific term rather than in popular language, it is generally acknowledged in Korean dialects. Conversely, Jeot, is a Korean word, frequently used in popular lan- guage, with two meanings; one indicates female breasts and the other is milk. Both words indicate female breasts in Korean various dialects. Yu-Bang and Jeot both imply the idea of “feeding a baby with milk” within the words themselves. As language is a symbolic representation of the culture of people who use it [59], Korean words for female breasts carry some of the symbolic meanings of female breasts in Korean culture. This is clearly demon- strated in the narratives of the cultural model of female breasts among the participants. Breast cancer implies the loss or deformation of a breast, and can lead a woman to relational detachment from her husband, and to social disconnection from the norms of society. The loss or deformation of a breast is therefore perceived as tragic because it devastates the patient’s role as a woman. In addition, a woman with a deformed breast may come to believe that she is no longer like the others in the collectivistic Korean culture. Unlikeness among the group members conveys disen- gagement from the social bonding in the collectivistic culture [31]. Therefore, the participants clearly articu- lated that breast cancer created the sense of a “perceived social death”. 5. CONCLUSIONS In this hermeneutic phenomenology study, Korean women’s cultural ways of perceiving, understanding, and interpreting female breasts and breast cancer were inter- pretively reconstructed and presented. The stories of these 40 Korean women depicted cultural models of breast-feeding mothers and women whose husbands see them as attractive, in the contexts of these relationships and the objectification of women’s bodies. Female breasts are interpreted as an external medium that con- nects women to their roles as mothers and wives. As breast cancer often causes the deformation or mutilation of this medium, it may lead women to detach from their previous relational and role-oriented identities. Cultural tradition, cultural concepts, and culture-related health beliefs of Korea were interwoven deeply in the women’s stories in reference to female breasts and breast cancer. This study illustrates the ramification of breast cancer in the lives of women whose ways of interpreting the world are constructed within a non-Western sociocultural Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 411 context. Although its limitations correspond to criticisms of applicability and consistency for interpretive studies, the cultural models of Korean women presented here coherently depict a lived manifestation of relational and collective self in the given context [60]. Understanding the indigenous cultural model of seeing, understanding, and interpreting the journey with breast cancer should precede any supportive breast cancer care for women with non-Western cultural backgrounds. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation (KRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. 331-2008-1- E00401). REFERENCES [1] Strauss, C. (1992) Models and motives. In: D’Andrade, R. and Strauss, C., Eds., Human Motives and Cultural Models, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1-20. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139166515.002 [2] D’Andrade, R. (1992) Schemas and motivation. In: D’Andrade R. and Strauss, C., Eds., Human Motives and Cultural Models, Cambridge University Press, New York, 23-44. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139166515.003 [3] Strauss, C. and Quinn, N. (1997) A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. Cambridge University Press, New York. [4] Ferlay, J., Shin, H.R., Bray, F., Forman, D., Mathers, C.D. and Parkin, D. (2010) GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. IARC Cancer Base No. 10, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon. [5] Arman, M. and Rehnsfeldt, A. (2002) Living with breast cancer—A challenge to expansive and creative forces. European Journal of Cancer Care, 11, 290-296. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2354.2002.00318.x [6] Coward, D.D. and Kahn, D.L. (2005) Transcending breast cancer: Making meaning from diagnosis and treat- ment. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23, 264-283. doi:10.1177/0898010105277649 [7] Elmir, R., Jackson, D., Beale, B. and Schmied, V. (2010) Against all odds: Australian women’s experiences of re- covery from breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 2531-2538. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03196.x [8] Manuel, J.C., Burwell, S.R., Crawford, S.L., Lawrence, R.H., Farmer, D.F., Hege, A., et al. (2007) Younger women’s perceptions of coping with breast cancer. Can- cer Nursing, 30, 85-94. doi:10.1097/01.NCC.0000265001.72064.dd [9] Rosedale, M. (2009) Survivor loneliness of women fol- lowing breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36, 175- 183. doi:10.1188/09.ONF.175-183 [10] Sealy, P.A. (2012) Autoethnography: Reflective journal- ing and meditation to cope with life-threatening breast cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 38-41. doi:10.1188/12.CJON.38-41 [11] Shaha, M. and Bauer-Wu, S. (2009) Early adulthood uprooted: Transitoriness in young women with breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 32, 246-255. [12] Taylor, E.J. (2000) Transformation of tragedy among women surviving breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Fo- rum, 27, 781-788. [13] Drageset, S., Lindstrøm, T.C., Giske, T. and Underlid, K. (2011) Being in suspense: Women’s experiences await- ing breast cancer surgery. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 1941-1951. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05638.x [14] Suh, E.E., Park, Y.H. and Kim, S. (2008) The patients’ experiences of the diagnosis and pre-treatment period of breast cancer. Journal of Korean Academy of Funda- mental Nursing, 15, 495-503. [15] Simpson, P. (2005) Hong Kong families and breast can- cer: Beliefs and adaptation strategies. Psycho-Oncology, 14, 671-683. doi:10.1002/pon.893 [16] Coyne, E. and Borbasi, S. (2009) Living the experience of breast cancer treatment: The younger women’s per- spective. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26, 6-13. [17] Nizamli, F., Anoosheh, M. and Mohammadi, E. (2011) Experiences of Syrian women with breast cancer regard- ing chemotherapy: A qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 13, 481-487. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00644.x [18] Rosedale, M. and Fu, M.R. (2010) Confronting the un- expected: Temporal, situational, and attributive dimen- sions of distressing symptom experience for breast can- cer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37, E28-E33. doi:10.1188/10.ONF.E28-E33 [19] Helms, R.L., O’Hea, E.L. and Corso, M. (2008) Body image issues in women with breast cancer. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13, 313-325. doi:10.1080/13548500701405509 [20] Frith, H., Harcourt, D. and Fussell, A. (2007) Anticipat- ing an altered appearance: Women undergoing chemo- therapy treatment for breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11, 385-391. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2007.03.002 [21] Klaeson, K., Sandell, K. and Berterö, C.M. (2011) To feel like an outsider: Focus group discussions regarding the influence on sexuality caused by breast cancer treat- ment. European Journal of Cancer Care, 20, 728-737. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01239.x [22] Ussher, J.M., Perz, J. and Gilbert E. (2012) Changes to sexual well-being and intimacy after breast cancer. Can- cer Nursing, 35, 456-465. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182395401 [23] Wilmoth, M.C. (2001) The aftermath of breast cancer: An altered sexual self. Cancer Nursing, 24, 278-286. doi:10.1097/00002820-200108000-00006 [24] Coward, D.D. and Kahn, D.L. (2004) Resolution of spiritual disequilibrium by women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31, E24-E31. doi:10.1188/04.ONF.E24-E31 [25] Swinton, J., Bain, V., Ingram, S. and Heys, S.D. (2011) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 412 Moving inwards, moving outwards, moving upwards: The role of spirituality during the early stages of breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 20, 640-652. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01260.x [26] Horgan, O., Holcombe, C. and Salmon, P. (2011) Ex- periencing positive change after a diagnosis of breast cancer: A grounded theory analysis. Psycho-Oncology, 20, 1116-1125. doi:10.1002/pon.1825 [27] Berterö, C. and Wilmoth, M.C. (2007) Breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment affecting the self: A meta- synthesis. Cancer Nursing, 30, 194-204. doi:10.1097/01.NCC.0000270707.80037.4c [28] Howard, A.F., Balneaves, L.G. and Bottorff, J.L. (2007) Ethnocultural women’s experiences of breast cancer: A qualitative meta-study. Cancer Nursing, 30, E27-E35. doi:10.1097/01.NCC.0000281737.33232.3c [29] Sheppard, L.A. and Ely S. (2008) Breast cancer and sexuality. The Breast Journal, 14, 176-181. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00550.x [30] Degner, L.F., Hack, T., O’Neil, J. and Kristjanson, L.J. (2003) A new approach to eliciting meaning in the con- text of breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 26, 169-178. doi:10.1097/00002820-200306000-00001 [31] Triandis, H. (1995) Individualism and collectivism. Westview Press, New York. [32] Lee, E.E., Tripp-Reimer,T., Miller, A.M., Sadler, G.R. and Lee, S. (2007) Korean American women’s beliefs about breast and cervical cancer and associated symbolic meanings. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34, 713-720. doi:10.1188/07.ONF.713-720 [33] Obeidat, R.F., Lally, R.M. and Dickerson, S.S. (2012) Arab American women’s lived experience with early- stage breast cancer diagnosis and surgical treatment. Cancer Nursing, 35, 302-311. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e318231db09 [34] Leung, P.P.Y. and Chan, C.L.W. (2010) Utilizing East- ern spirituality in clinical practice: A qualitative study of Chinese women with breast cancer. Smith College Stud- ies in Social Work, 80, 159-183. doi:10.1080/00377317.2010.483673 [35] Banning, M., Hafeez, H., Faisal, S., Hassan, M. and Zafar, A. (2009) The impact of culture and sociological and psychological issues on Muslim patients with breast cancer in Pakistan. Cancer Nursing, 32, 317-324. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b240f [36] Banning, M., Hassan, M., Faisal, S. and Hafeez, H. (2010) Cultural interrelationships and the lived experience of Pakistani breast cancer patients. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14, 304-309. [37] Lim, J.W., Baik, O.M. and Ashing-Giwa, K.T. (2012) Cultural health beliefs and health behaviors in Asian American breast cancer survivors: A mixed-methods ap- proach. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 388-397. doi:10.1188/12.ONF.388-397 [38] Ormiston, G.L. and Schrift, A.D. (1990) The hermeneu- tic tradition: From Ast to Ricoeur. State University of New York Press, Albany. [39] Geanellos, R. (1998) Hermeneutic philosophy. Part I: implications of its use as methodology in interpretive nursing research. Nursing Inquiry, 5, 154-163. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1800.1998.530154.x [40] Ricoeur, P. (1971) The model of the text: Meaningful action considered as a text. Social Research, 38, 529- 562. [41] Caelli, K. (2000) The changing face of phenomenologi- cal research: Traditional and American phenomenology in nursing. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 366-377. doi:10.1177/104973200129118507 [42] Suh, E.E. (2008) The sociocultural context of breast can- cer screening among Korean immigrant women. Cancer Nursing, 31, E1-E10. doi:10.1097/01.NCC.0000305742.56829.fc [43] Suh, E.E. (2012) The effect of P6 acupressure and nurse- provided counseling on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, E1-E9. doi:10.1188/12.ONF.E1-E9 [44] Walters, A.J. (1994) An interpretive study of the clinical practice of critical care nurses. Contemporary Nurse, 3, 21-25. doi: 10.5172/conu.3.1.21 [45] Suh. E.E., Kagan, S.H. and Strumpf, N.E. (2009) Cul- tural competence in qualitative interview methods with Asian Americans. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20, 194-201. doi:10.1177/1043659608330059 [46] Koch, T. (1995) Interpretive approaches in nursing re- search: The influence of Husserl and Heidegger. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 21, 827-836. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21050827.x [47] Benner, P. (1985) Quality of life: A phenomenological perspective on explanation, prediction, and understand- ing in nursing science. Advances in Nursing Science, 8, 1-14. [48] Boyatzis, R.E. (1998) Transforming qualitative informa- tion: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage publication, Thousand Oaks. [49] Leonard, V.W. (1989) A Heideggerian phenomenologic perspective on the concept of the person. Advances in Nursing Science, 11, 40-55. [50] Koch, T. (1994) Establishing rigour in qualitative re- search: The decision trail. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19, 976-986.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01177.x [51] Cho, H.J. (1988) Women and men of Korea. Munhak and Gisung, Seoul. [52] Sim, Y., Jeong, J. and Yun, J. (2000) Mo-Seong-Ui Dam-Non-GwaHyeon-Sil (Discourse and reality of mo- therhood). Nanam, Seoul. [53] Kim, E.H. (1998) The social reality of Korean American women: Toward crashing with the Confucian ideology. In: Song, Y.I. and Moon, A., Eds., Korean American Women from Tradition to Modern Feminism, Praeger, Westport, 23-33. [54] Cho, H.J. (1998) Reflection on modernism and feminism: Women and men of Korea II. TtoHanauiMunhwa, Seoul. [55] Kramer, E.J., Ivey, S.L. and Ying, Y.W. (1999) Immi- grant women’s health: Problems and solutions. Jossey- Bass, San Francisco. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. Suh / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 404-413 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 413 OPEN ACCESS [56] Song, Y.I. and Moon, A. (1998) Korean American women: From tradition to modern feminism. Praeger, Westport. [57] Geum, J. (2003) Hyeon-Dae-Han-Gug-Yu-Gyo-WaJeon- Tong (Modern Korean Confucianism and tradition). Seoul National University Press, Seoul. [58] Im, H. (2002) Sa-Ju-Pal-Ja (Four pillars and fate). Samho Media, Seoul. [59] Duranti, A. (1997) Linguistic anthropology. Cambridge University Press, New York. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511810190 [60] Sedikides, C. and Brewer, M.B. (2001) Individual self, relational self, collective self. Psychology Press, Phila- delphia.

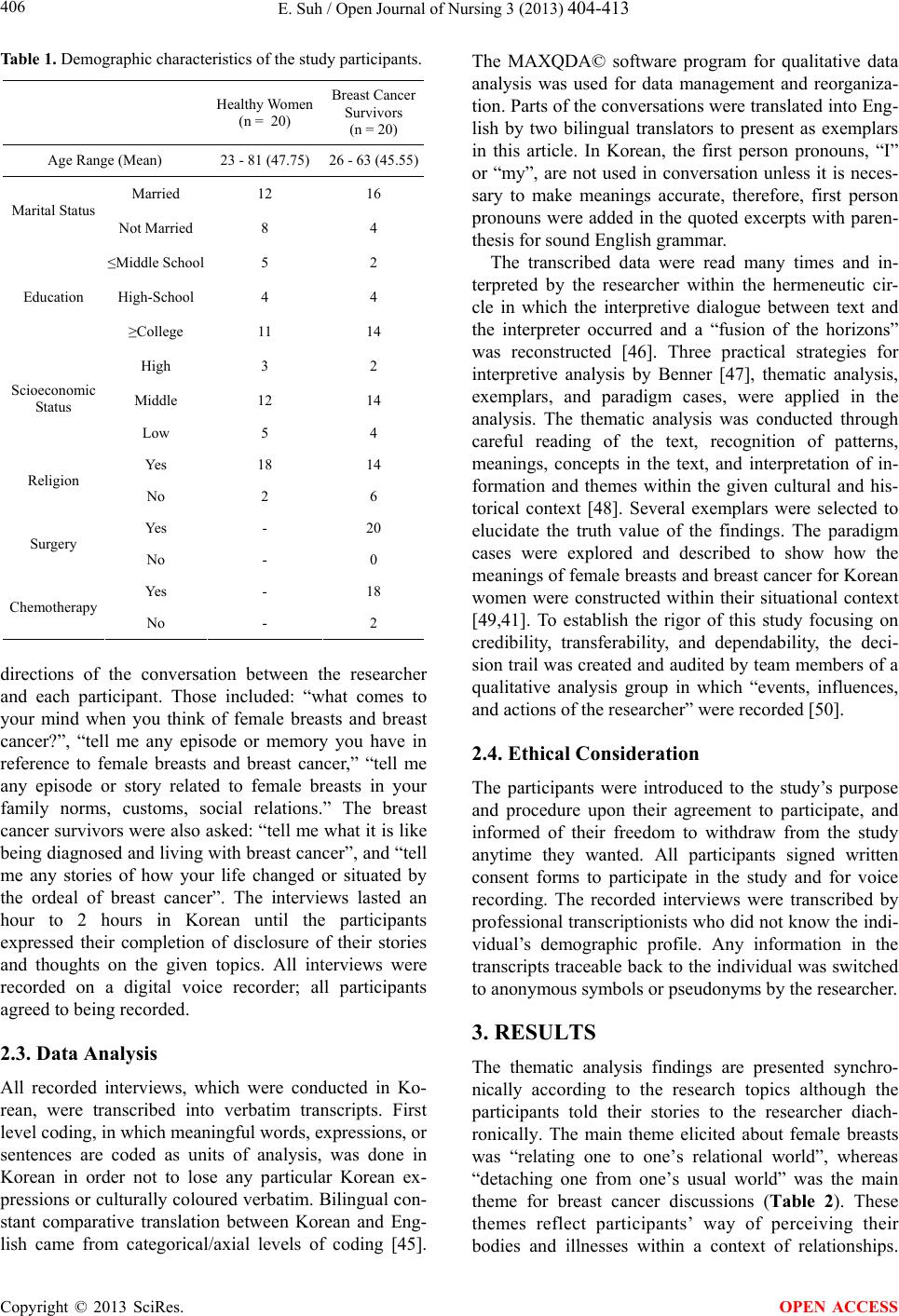

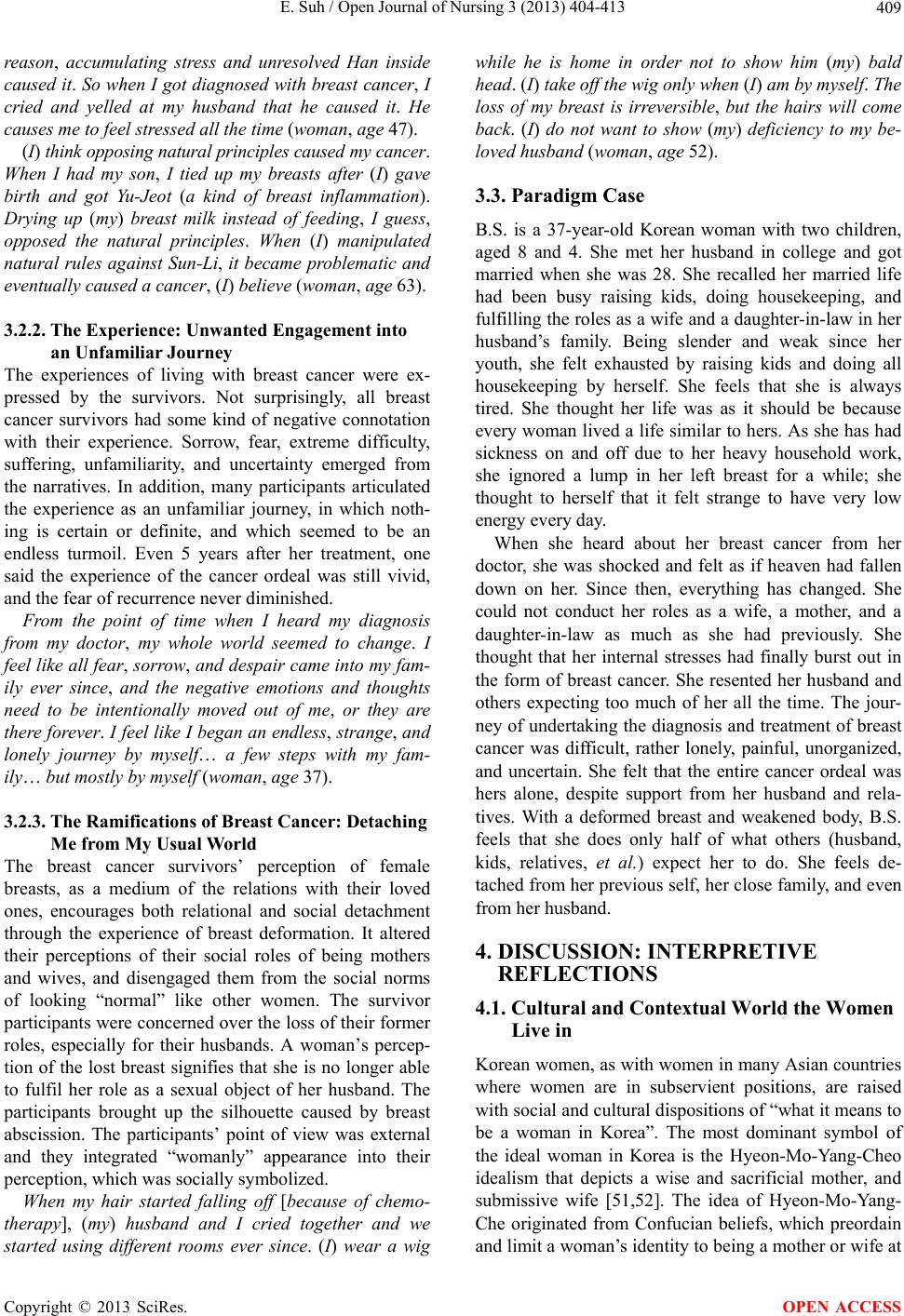

|