Journal of Biomaterials and Nanobiotechnology

Vol.11 No.01(2020), Article ID:96880,16 pages

10.4236/jbnb.2020.111003

Electrochemical Evaluation of Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Derivative with Potential Anticancer Activity: Studies of Glassy Carbon/CNT and Gold Electrodes Both Modified with PAMAM

Marílya Palmeira Galdino da Silva1, Ygor Mendes de Oliveira1, Anna Caroline Lima Candido1, João Xavier de Araújo-Júnior1,2, Érica Erlanny da Silva Rodrigues1, Kadja Luana Chagas Monteiro2, Thiago Mendonça de Aquino1, Fabiane Caxico de Abreu1*

1Institute of Chemistry and Biotechnology, Federal University of Alagoas, Maceió, AL, Brazil

2Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Federal University of Alagoas, Maceió, AL, Brazil

Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 1, 2019; Accepted: December 2, 2019; Published: December 5, 2019

ABSTRACT

Aminoguanidine hydrazones (AGHs) are a class of compounds that have interesting pharmacological activities. They are derived from the same chemical group as aminoguanidine, so it has mixed properties (receptor and donor) in the formation of hydrogen bonds. Its anticancer agent properties were recently highlighted, but the molecules of this class have solubility in aqueous solutions that can be considered low. The identification of this class, by a simple, sensitive and low-cost technique, such as electrochemistry, which also allows the evaluation of its solubilization process through agents such as PAMAM dendrimer is the main objective of the work described here. The electrochemical response of the LQM10 (AGH derivative) was evaluated, as well as its behavior in different electrochemical sensors. Electrochemical experiments were performed in buffered (phosphate at pH 7.02 and acetate at 4.5). LQM10 has a reversible oxidation peak with a potential of +0.22 V. It was efficiently detected in different electrodes tested (glass carbon/CNT, glass carbon/CNT/PAMAM), which proves the viability of the electrodes for various analyses and has the determination of the apparent constant association, indicating its interaction with the analysis that is higher in the presence of the PAMAM encapsulating agent. This was corroborated by the results for the modified gold electrode with MUA and PAMAM. The sum of the results shows the possibility of electrochemically evaluating the Aminoguanidine hydrazone derivative, the viability of electrodes employed and the greater solubilization of LQM10 in the presence of the PAMAM dendrimer.

Keywords:

Drug Delivery, Aminoguanidine Hydrazone, Modified Electrode, PAMAM

1. Introduction

Aminoguanidine hydrazine derivatives are bioactive compounds that have been intensively studied for their different (and interesting) biological activities, such as in the treatment of hypertension (Guanabenz) [1] [2] [3], or antiarrhythmic [4] [5] ; nonpeptide NPFF1 Receptor Antagonists reverse opioid-induced hyperalgesia [6] ; as modulators of norfloxacin resistance in S. aureus that overexpress the efflux pump of NorA [7] ; and anticancer [8].

The activity anticancer of Aminoguanidine hydrazine (AGH) of this class of compound a drug of considerable pharmacological interest. They are derived from the same chemical group as aminoguanidine, so it has mixed properties (receptor and donor) in the formation of hydrogen bonds. Its anticancer agent properties were recently highlighted, but the molecules of this class have solubility in aqueous solutions that can be considered low [8]. Studies the association of this class the compound with some carriers as cyclodextrin, liposomes or linear polymers were few reported [9].

In last years, polymer-based nanomedicine has received increasing attention because of its ability to improve therapeutic efficacy in cancer treatment [10] [11] [12]. Dendritic scaffold has been found to be suitable carrier for a variety of drugs including anticancer, anti-viral, anti-bacterial, anti-tubercular, with capacity to improve solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs [10] [13]. A promising alternative to solubilize AGH in aqueous media is the use of dendrimers, which are highly branched polymers and that their physicochemical properties, such as high control in their structure, size, shape, density and surface groups with many functionalities, they are ideal carriers in biomedical applications such as drug transport at specific sites in the biological system [11] [14] [15] [16]. Among the available dendrimers, the polyamidoamine dendrimer (PAMAM) already studied with several antitumor drugs and the first to present its complete series, that is, from generation 0 to 10 (G0 - G10), the lowest generation (G0 - G3) almost has no cytotoxicity [17] [18].

Electrochemical technique in association with PAMAM, has already been used for numerous applications, including as an immobilized substrate for glassy carbon electrodes [19] [20] [21] and/or modification of the surface of gold electrodes [21]. Recently our group related dendrimers derivatives for the construction of chemical sensors [22] and inclusion complexation of surface-confined with PAMAM on electrodes using cyclic voltammetry [23] [24]. These methodologies will also be used here to evaluate the formation of inclusion complexes between LQM10 and dendrimers through electrochemistry to investigate the type of interaction between Aminoguanidine hydrazone and generation 3 PAMAM dendrimer, immobilized on a gold electrode and vitreous carbon/Carbon Nanotubes.

2. Materials and Apparatus

The analytical grade reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Acros Chemical Co. or Merck. The substance LQM10 (2E)-2-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidene)hydrazinecarboximidamide was synthesized using a previously described procedure [8].

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) experiments were performed using a conventional undivided three-electrode cell and an AutolabPGSTAT-30 potentiostat (Eco Chemie, Utrecht, Netherlands) coupled to a microcomputer interfaced by GPES 4.9 software. The working electrodes were a glassy carbon (GC-diameter = 3 mm), gold bead modified electrode with β-CDSH and PAMAM 3G, an Ag|AgCl, Cl− (saturated) reference electrode and a Pt wire as the counter electrode. The GC was cleaned by polishing with alumina on a polishing felt. The gold bead working electrode was prepared by annealing the tip of a gold wire (99.999%, 0.5 mm diameter) in an oxygen gas flame and the voltammetric response of this electrode was established as 0.2 mol/L Na2SO4 after modification. Inert gas was used to degas the solution and the solution was covered with a nitrogen blanket during some experiments. The pH was measured (QUIMIS). All experiments were conducted at room temperature (25˚C ± 2˚C)

The solution used in the protic media was performed using a phosphate buffer with pH 7.02 (ionic strength 0.2) or ethanol (EtOH) at 5% and acetate buffer with pH 4.5 (ionic strength 0.2). PAMAM generation 3 (Aldrich) was also added to the phosphate buffer in order to evaluate its interaction with LQM10 over time.

2.1. Preparation of Carbon Nanotubes Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode (CNT)

The glass carbon electrode was modified with CNT in two different ways.

Method 1: 1.0 mg CNT was suspended in 1.0 mL of DMF and dispersed on the ultrasound for 2 h before being deposited on the surface of GC electrodes. 10 μL were added to the solution (1 μL added at a time). The electrode was taken to the stove at 80˚C for 10 min (at each addition).

Method 2: The procedure of Method 1 was repeated and then a 10 μL aliquot of PAMAM 3G was added to the surface of the CNT-modified electrode and dried over N2 gas flow before proceeding with the analysis.

2.2. Preparation of the Gold Modified Electrode with PAMAM Generation 3

Gold electrode modification with PAMAM generation 3 occurred in two stages and followed the methodology described in the literature [25]. After being cleaned by heating in a flame, step 1 involved clean gold surfaces being functionalized through thiol-linked self-assembled monolayers (SAM) of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA), immersing them in 1 × 10−3 mol/L of MUA methanolic solutions at 25˚C for 24 h. Moving on to the Step 2, PAMAM dendrimers were chemically linked to the functionalized gold electrodes with MUA by promoting the creation of amide bonds between the COOH extremities of the MUA and the amine groups on the dendrimers. Such bonds were obtained by immersing the thiolated gold substrates in methanolic solutions containing 5 × 10−3 mol/L of EDC (to promote the creation of the amide bonds) and 21 × 10−6 mol/L of PAMAM dendrimer generation 3 for 12 h at 25˚C. Finally, the dendrimer-functionalized gold surfaces were then washed gently in methanol at room temperature.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Electrochemical Behavior of LQM10

LQM10 (Figure 1), as well as the other Aminoguanidine hydrazones, did not have its electrochemical profile determined until then, so the initial analyzes sought to verify its behavior by cyclic voltammetry in GCE, in a protic medium, phosphate buffer with pH 7.02 in 10% of Ethanol PA, due to its low solubility in aqueous medium. The first scanning was performed from 0 to +1.2 V (oxidation) and the second from −1.2 to 0 V (reduction), the last being performed in an atmosphere of N2 gas to avoid any interference of O2 in the reaction (Figure 2).

The compound being oxidized shows a pair of anodic peaks, Epa1 and Epc1, at +0.267 V and +0.239 V, respectively (Figure 2(a)), at 0.050 V/s. Already to be reduced, no signal was observed on the voltammogram, indicating that the LQM10 does not undergo reduction process (Figure 2(b)).

The analysis of the electrochemical parameters, anodic peak currents, obtained in the LQM10 studies showed that the mass transport to the electrode surface is controlled by diffusional process (spontaneous movement of the chemical species due to the formation of a concentration gradient of the analyte of interest), in accordance with the linearity between the anodic peak currents (Ipa1) as a function of the square root of the sweep velocity (ѵ1/2). When evaluating the values of anodic and cathodic currents it is concluded that the oxidation process represented in the voltammogram is reversible, according to diagnostic tests defined in the specific literature [26].

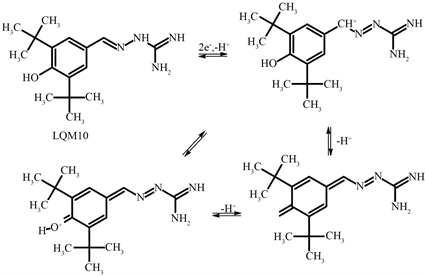

The electrochemical mechanism for oxidation process may be associated probably the oxidation of the guanidine Hydrazone group generating the quinone methide derivative after oxidation process of the 2e− following the deprotonation step as showed in Scheme 1.

In this work, we evaluated the electrochemical behavior of the LQM10 against two differently modified electrodes, whose results will be presented in the following sessions and are summarized in Figure 3.

Scheme 1. Probable oxidation mechanism of LQM10.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of LQM10.

Figure 2. Electrochemical profile of LQM10 by cyclic voltammetry (CV), in ethanolic aqueous medium (10%), phosphate buffer pH 7.02, in GCE, 0.05 V·s−1: (a) oxidation and (b) reduction.

Figure 3. Schematic model with the modifications in glassy carbon electrode and gold and summary of the results obtained by them in the analysis of LQM10.

3.2. Electrochemical Behavior of LQM10 with Modified GCE

3.2.1. GCE Modified with CNT (GCE-CNT)

There is a clear indication, in the literature, of the applicability of CNT as an efficient modifier of the glassy carbon surface due to its chemical and physical properties such as surface area, the possibility of adhering many functional groups to the surface and increasing the transfer speed of electron at the interface of the electrode [27] [28] [29].

In GCE-CNT, it is possible to notice the increase in the current of the characteristic peaks of the LQM10, with displacement to more positive potential of Epa1 and to potentials closer to 0V in the case of Epa2, after 50 consecutive sweeps, under the same conditions and with concentration of LQM10 in the constant medium (Figure 4(a)). Indicating the durability of the electrode and the facility of the oxidation process when modified with CNT [29].

It was possible to construct a calibration curve for LQM10 in phosphate buffer of 0.2 mol/L, pH 7.02, using the GCE-CNT sensor, varying the concentration of LQM10 (10−6 to 8 × 10−6 mol/L) shown in Figure 4(b). With the anodic peak current, it was possible to determine constant stability or association by electrochemical experiments under these conditions (KF), using the following equation (derived from the isotherm of Benesi-Hildebrand) (Equation (1)):

(1)

where [LQM10]0 is the concentration of the electroactive specie; I is the peak current measured for each concentration of the LQM10 molecule; Imax is the maximum peak current; and K is the formation constant of the LQM10 molecule with CNT anchored in electrode surface [23] [24] [29] [30] [31]. Having as the value of KF = 4.4 × 104 L/mol (Figure 4(c)).

When correlating the current values versus the concentration analyzed, it was possible to calculate the limits of detection (LD) and quantification (LQ) for LQM10 in GCE-CNT, respectively 0.35 × 10−6 mol/L and 1.17 × 10−6 mol/L.

Figure 4. CV of LQM10 in mixed medium (phosphate buffer, pH 7.02, and 10% ethanol PA) on a modified glass carbon electrode with CNT, 0.05 V·s−1: (a) 50 scans of LQM10 (10−4 mol/L); (b) by varying the concentrations of LQM10 (10−6 to 8 × 10−5 mol/L); (c) graph of determination of the equilibrium constant of LQM10:CNT (([LQM10]/I) × [LQM10]).

3.2.2. GCE Modified with CNT and PAMAM G3 (GCE/CNT/PAMAM G3)

As previously mentioned, the presence of CNT on the surface of the electrode makes possible the adhesion of groups to the glassy carbon. Thus the CNT served as support for PAMAM 3G on the surface of the electrode in a second modification. The literature already reports the efficiency in the association of CNT and PAMAM [23] [32] [33] [34], which was characterized by van der Waals interactions between the surface of the CNT and the amino termination of PAMAM, occurring even more strongly on the electrolytic surface of glassy carbon and gold [35]. The use of this methodology allows the production of a fairly dispersive and visually uniform modification on the surface of the electrode [35] [36].

This second modified electrode showed the same behavior as the electrode modified only with CNT, regarding the displacement of the potential values of Epa1 and Epa2. However, different from the previous case, the values of currents decreased as more scans were performed, the experiment occurred in the same conditions of medium and concentration of LQM10 as the previous one, such result can be explained by the occurrence of adsorption of LQM10 on surface of the electrode due your interaction with PAMAM G3 (Figure 5(a)) [23]. But, it is possible to observe that the current value in the first scan is much larger in the presence of PAMAM than in its absence (electrode only with CNT) and that even with the adsorption process, after 50 scans, the presence of the substance in solution is clearly visible. It is important to reaffirm the reports that this polymer (PAMAM) is able to increase the concentration of hydrophobic molecules in the interface electrode-solution [37] [38], so it is believed that it is possible to correlate the interaction between the dendrimer and an improvement in the solubility of the compounds.

Such interaction can be measured quantitatively by the application of Equation (1) to the calibration curve obtained by the voltammograms currents of Figure 5(b) and Figure 5(c), where the concentrations of LQM10 ranged from 10−6 to 8 × 10−6 mol/L, thus obtaining a KF = 1.23 × 106 L/mol, a value almost 10 times higher than the one presented by Silva et al. [24] for a nitro compound and 100 times higher than the electrode modified with CNT alone, which ratifies the hypothesis of the improvement in solubility in the presence of the dendrimer. Comparing the two calibration curves (Figure 6), the higher values of currents in the presence of PAMAM are again evidenced.

For GCE-CNT-PAMAM G3 the values of LD and LQ were respectively 0.06 × 10−6 mol/L and 0.2 × 10−6 mol/L, these values compared to those obtained by GCE-CNT electrode, ratify the higher sensitivity in the presence of PAMAM G3.

3.3. Electrochemical Behavior of LQM10 Interaction with PAMAM G3 Immobilized on a Gold Electrode

By evaluating the structure of the PAMAM dendrimer, its inner, terminal groups with hydrophobic regions, it is concluded that the stoichiometry of the inclusion complex formed with it will probably involve more than one molecule of the drug for each mole of PAMAM [39]. In the literature, the Benesi-Hildebrand equation is applicable to interactions with 1:1 or 1:2 stoichiometry to calculate the equilibrium constant of a complex [40] [41]. In a previous work [24], based on the data of BOBROVNIK [42] and BUCZKOWSKI and collaborators [43], a methodology has been developed that shows that more active PAMAM sites are available for interaction, so that the new calculated constant takes all these factors into account.

Figure 5. CV of LQM10 in mixed medium (phosphate buffer, pH 7.02, and 10% ethanol PA) on a modified glass carbon electrode with CNT + PAMAM G3, 0.05 V·s−1: (a) 50 scans of LQM10 (10−4 mol/L); (b) by varying the concentrations of LQM10 (10−6 to 8 × 10−5 mol/L); (c) graph of determination of the equilibrium constant of LQM10: CNT + PAMAM G3 (([LQM10]/I) × [LQM10]).

Figure 6. Concentration Curve × [Current]. Modified Vitreous Carbon Electrode: with CNT + PAMAM 3G (■) and CNT (●).

The first step is to evaluate the oxidation process of LQM10 on the MUA-functionalized gold electrode (AU/MUA) in aqueous-ethanol medium (10% of ethanol P.A.), as can be observed in Figure 7(a). The concentration of LQM10 in solution ranged from 10−6 to 8 × 10−6 mol/L and the peak currents Epa2 obtained are considered to refer to a non-encapsulated substance. Since in Figure 7(b) it is observed the voltammograms of LQM10 at the same concentrations as previously, however, in this case, the PAMAM G3 is immobilized on the surface of the gold electrode already functionalized with MUA (AU/MUA/PAMAM), as described in the methodology [24]. The difference between the peak currents Epa2 of the two electrodes corresponds to the LQM10 that interacted with the PAMAM. Then, with this information, the binding of the number of molecules of associated ligands per 1 mole of combined receptor and the concentration of the substance added to the medium have a hyperbolic character(Equation (2)) [23] [24] [42] [43] :

(2)

where ΔI is the difference between current values with the electrodes Au/MUA/ PAMAM and Au/MUA (IP-IM), generated by the oxidation of LQM10 in different concentrations, compared to Au/MUA/PAMAM (IP) and Au/MUA (IM); n is the number of active sites where the drug can bind in the dendrimer; K is the equilibrium constant of the formed complex; and [LQM10] is the concentration of LQM10.

To facilitate the analysis of the data, the linearization of the previous equation (Equation (3)), known as the Scatchar-Klort equation [23] [24] [42] [43] was made, to which it was adapted to the electrochemical parameters [25] :

(3)

Figure 7(c) depicts the line generated by the equation from the experimental data used to obtain the equilibrium interaction constant of LQM10-PAMAMG3

Figure 7. Cyclic voltammograms for LQM10 of 10−6 to 8 × 10−6 mol/L with: (a) Au/MUA; b) Au/MUA/PAMAM electrode; (c) Analytical curve generated by the concentration and current values of LQM10 with Au/MUA/PAMAM G3 electrode. Phosphate buffer, pH 7.02, 10% ethanol, 0.05 V·s−1.

in solution. The reverse current dependence (ΔI by the added LQM10 concentration) (Figure 7(c)) is described by the linear equation: Y = (1.623)X + (4.857) × 10−6 (R2 = 0.9961). The value of K between LQM10 and PAMAM G3 of the Scatchard-Klotz found through the adapted equation was 2.06 × 105 L/mol. This value of K confirms the importance of PAMAM in the formation of the complex and, consequently, in the solubility of the compound, in view of being very similar to the value presented in previous work where the study was done with the nitro compound 6CN10 [24] and 10 times higher than the analysis in this system for quinone β-lapachone [23].

4. Conclusions

The analyzed compound, (2E)-2-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidene)hydrazineecarboximidamide, LQM10, in protic medium by the cyclic voltammetry technique, shows a reversible oxidation peak. The probable mechanism involves the oxidation (+2e−/H+) of the Aminoguanidine hydrazone group leading to the quinone methide derivative.

The LQM10 can be detected using CNT-modified glassy carbon electrode and when the PAMAM G3 dendrimer was also adsorbed on its surface, the response was more sensible due to observed current increase. Applying the methodology of modifying the surface of the gold electrode with PAMAM, it was possible to evaluate the complex LQM10:PAMAM and a formation constant can be calculated.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Brazilian agencies CNPq, CAPES, FAPEAL and UFAL for financial support

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

da Silva, M.P.G., de Oliveira, Y.M., Candido, A.C.L., de Araújo-Júnior, J.X., da Silva Rodrigues, É.E., Monteiro, K.L.C., de Aquino, T.M. and de Abreu, F.C. (2020) Electrochemical Evaluation of Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Derivative with Potential Anticancer Activity: Studies of Glassy Carbon/CNT and Gold Electrodes Both Modified with PAMAM. Journal of Biomaterials and Nanobiotechnology, 11, 33-48. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbnb.2020.111003

References

- 1. Chaffman, M., Heel, R.C., Brogden, R.N., Speight, T.M. and Avery, G.S. (1984) Indapamide a Review of Its Pharmacodynamic Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy in Hypertension. Drugs, 28, 189-235. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-198428030-00001

- 2. Schäfer, S.G., Kaan, E.C., Christen, M.O., Löw-Kröger, A., Mest, H.-J. and Molderings, G.-J. (1995) Why Imidazoline Receptor Modulator in the Treatment of Hypertension? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 763, 659-672. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32460.x

- 3. Sica, D.A. (2007) Centrally Acting Antihypertensive Agents: An Update. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 9, 399-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.07161.x

- 4. Volkmann, H., Hoffmann, A., Kühnert, H., Dannberg, G., Heinke, M., Reimann, I., Marschner, J.P. and Farker, K. (1993) Clinical-Electrophysiologic Studies on the Actions of the Anti-Arrhythmic Substance AWD-G256 in Man. Pharmazie, 48, 380-385. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8327568

- 5. Farker, K., Henschel, L., Marschner, J.P., Reimann, I., Volkmann, H. and Hoffmann, A. (1992) Investigations into a New Antiarrhythmic Substance Z-2-Amino-5-Chlor-Benzophenon-Amidin-Hydralazin in Humans. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology, 30, 513-514. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1490815

- 6. Hammoud, H., Elhabazi, K., Quillet, R., Bertin, I., Utard, V., Laboureyras, E., Bourguignon, J.-J., Bihel, F., Simonnet, G., Simonin, F. and Schmitt, M. (2018) Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Derivatives as Nonpeptide NPFF1 Receptor Antagonists Reverse Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 9, 2599-2609. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00099

- 7. Dantas, N., de Aquino, T.M., de Araújo-Júnior, J.X., da Silva-Júnior, E., Gomes, E.A., Gomes, A.A.S., Siqueira-Júnior, J.P. and Mendon ça Junior, F.J.B. (2018) Aminoguanidine Hydrazones (AGH’s) as Modulators of Norfloxacin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus That Overexpress NorA Efflux Pump. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 280, 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2017.12.009

- 8. França, P.H.B., Da Silva-Júnior, E.F., Aquino, P.G.V., Santana, A.E.G., Ferro, J.N.S., De Oliveira Barreto, E., Do ó Pessoa, C., Meira, A.S., De Aquino, T.M., Alexandre-Moreira, M.S., Schmitt, M. and De Araújo-Júnior, J.X. (2016) Preliminary in Vitro Evaluation of the Anti-Proliferative Activity of Guanylhydrazone Derivatives. Acta Pharmaceutica, 66, 129-137. https://doi.org/10.1515/acph-2016-0015

- 9. Arndt, D., Fichtner, I. and Nissen, E. (1987) Liposomes as Carrier of Methyl-GAG. Oncology, 44, 257-262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000226490

- 10. Abedi-Gaballu, F., Dehghan, G., Ghaffari, M., Yekta, R., Abbaspour-Ravasjani, S., Baradaran, B., Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi, J. and Hamblin, M.R. (2018) PAMAM Dendrimers as Efficient Drug and Gene Delivery Nanosystems for Cancer Therapy. Applied Materials Today, 12, 177-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2018.05.002

- 11. Li, J., Liang, H., Liu, J. and Wang, Z. (2018) Poly (amidoamine) (PAMAM) Dendrimer Mediated Delivery of Drug and pDNA/siRNA for Cancer Therapy. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 546, 215-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.05.045

- 12. Das, K., Beans, C., Holsbeek, L., Mauger, G., Berrow, S., Rogan, E. and Bouquegneau, J. (2003) Marine Mammals from Northeast Atlantic: Relationship between Their Trophic Status as Determined by δ13C and δ15N Measurements and Their Trace Metal Concentrations. Marine Environmental Research, 56, 349-365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-1136(02)00308-2

- 13. Bikiaris, D. (2012) Nanomadicine in Cancer Treatment: Drug Targeting and the Safety of the Used Materials for Drug Nanoencapsulation. Biochemical Pharmacology, 1, 121-123. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0501.1000e122

- 14. Matsuura, S., Katsumi, H., Suzuki, H., Hirai, N., Hayashi, H., Koshino, K., Higuchi, T., Yagi, Y., Kimura, H., Sakane, T. and Yamamoto, A. (2018) l-Serine-Modified Polyamidoamine Dendrimer as a Highly Potent Renal Targeting Drug Carrier. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 10511-10516. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808168115

- 15. Paolini, A., Leoni, L., Giannicchi, I., Abbaszadeh, Z., D’Oria, V., Mura, F., Dalla Cort, A. and Masotti, A. (2018) MicroRNAs Delivery into Human Cells Grown on 3D-Printed PLA Scaffolds Coated with a Novel Fluorescent PAMAM Dendrimer for Biomedical Applications. Scientific Reports, 8, Article No. 13888. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32258-9

- 16. Svenson, S. and Tomalia, D.A. (2012) Dendrimers in Biomedical Applications— Reflections on the Field. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 64, 102-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.030

- 17. Pan, S., Cao, D., Fang, R., Yi, W., Huang, H., Tian, S. and Feng, M. (2013) Cellular Uptake and Transfection Activity of DNA Complexes Based on Poly(ethylene glycol)-Poly(l-glutamine) Copolymer with PAMAM G2. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 1, 5114-5127. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3tb20649a

- 18. Taghavi Pourianazar, N., Mutlu, P. and Gunduz, U. (2014) Bioapplications of Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) Dendrimers in Nanomedicine. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 16, 2342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-014-2342-1

- 19. Devi, C.L. and Narayanan, S.S. (2019) Poly(amido amine) Dendrimer/Silver Nanoparticles/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes/Poly(neutral red)-Modified Electrode for Electrochemical Determination of Paracetamol. Ionics (Kiel), 25, 2323-2335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-018-2609-0

- 20. Kim, T.H., Choi, H.S., Go, B.R. and Kim, J. (2010) Modification of a Glassy Carbon Surface with Amine-Terminated Dendrimers and Its Application to Electrocatalytic Hydrazine Oxidation. Electrochemistry Communications, 12, 788-791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2010.03.034

- 21. Astruc, D. (2012) Electron-Transfer Processes in Dendrimers and Their Implication in Biology, Catalysis, Sensing and Nanotechnology. Nature Chemistry, 4, 255-267. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1304

- 22. Bustos, E., Manríquez, J., Juaristi, E., Chapman, T.W. and Godínez, L.A. (2008) Electrochemical Study of β-Cyclodextrin Binding with Ferrocene Tethered onto a Gold Surface via PAMAM Dendrimers. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 19, 1010-1016. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532008000500028

- 23. Candido, A.C.L., da Silva, M.P.G., da Silva, E.G. and de Abreu, F.C. (2018) Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Characterization of the Interaction between β-Lapachone and PAMAM Derivatives Immobilized on Surface Electrodes. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry, 22, 1581-1590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-018-3880-8

- 24. da Silva, M.P.G., Candido, A.C.L., Lins, S. de L., de Aquino, T.M., Mendonça, F.J.B. and de Abreu, F.C. (2017) Electrochemical Investigation of the Toxicity of a New Nitrocompound and Its Interaction with β-Cyclodextrin and Polyamidoamine Third-Generation. Electrochimica Acta, 251, 442-451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.08.111

- 25. Tang, B., Liang, H.-L., Xu, K.-H., Mao, Z., Shi, X.-F. and Chen, Z.-Z. (2005) An Improved Synthesis of Disulfides Linked β-Cyclodextrin Dimer and Its Analytical Application for Dequalinium Chloride Determination by Spectrofluorimetry. Analytica Chimica Acta, 554, 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2005.08.048

- 26. Inesi, A. (1986) Instrumental Methods in Electrochemistry. Bioelectrochemistry and Bioenergetics, 15, 531. https://doi.org/10.1016/0302-4598(86)85047-4

- 27. Jiang, Q., Song, L.J., Yang, H., He, Z.W. and Zhao, Y. (2008) Preparation and Characterization on the Carbon Nanotube Chemically Modified Electrode Grown in Situ. Electrochemistry Communications, 10, 424-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2008.01.006

- 28. Alarcón-Angeles, G., Pérez-López, B., Palomar-Pardave, M., Ramírez-Silva, M.T., Alegret, S. and Merkoçi, A. (2008) Enhanced Host-Guest Electrochemical Recognition of Dopamine Using Cyclodextrin in the Presence of Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon, 46, 898-906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2008.02.025

- 29. Ferreira, F.D.R., da Silva, E.G., De Leo, L.P.M., Calvo, E.J., Bento, E.D.S., Goulart, M.O.F. and de Abreu, F.C. (2010) Electrochemical Investigations into Host-Guest Interactions of a Natural Antioxidant Compound with β-Cyclodextrin. Electrochimica Acta, 56, 797-803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2010.09.066

- 30. Maeda, Y., Fukuda, T., Yamamoto, H. and Kitano, H. (1997) Regio- and Stereoselective Complexation by a Self-Assembled Monolayer of Thiolated Cyclodextrin on a Gold Electrode. Langmuir, 13, 4187-4189. https://doi.org/10.1021/la9701384

- 31. Damos, F.S., Luz, R.C.S., Sabino, A.A., Eberlin, M.N., Pilli, R.A. and Kubota, L.T. (2007) Adsorption Kinetic and Properties of Self-Assembled Monolayer Based on Mono(6-deoxy-6-mercapto)-β-cyclodextrin Molecules. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 60, 1181-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2006.11.004

- 32. Zeng, Y.-L., Huang, Y.-F., Jiang, J.-H., Zhang, X.-B., Tang, C.-R., Shen, G.-L. and Yu, R.-Q. (2007) Functionalization of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimer for Mediator-Free Glucose Biosensor. Electrochemistry Communications, 9, 185-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2006.08.052

- 33. Zhu, X., Ai, S., Chen, Q., Yin, H. and Xu, J. (2009) Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of Avian Influenza Virus Genotype Utilizing Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes-Cobalt Phthalocyanine-PAMAM Nanocomposite Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Electrochemistry Communications, 11, 1543-1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2009.05.055

- 34. Wu, M.-S., Chen, R.-N., Xiao, Y. and Lv, Z.-X. (2016) Novel “Signal-On” Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor for the Detection of PSA Based on Resonance Energy Transfer. Talanta, 161, 271-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2016.08.060

- 35. Vijayaraghavan, G. and Stevenson, K.J. (2007) Synergistic Assembly of Dendrimer-Templated Platinum Catalysts on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotube Electrodes for Oxygen Reduction. Langmuir, 23, 5279-5282. https://doi.org/10.1021/la0637263

- 36. Herrero, M.A., Guerra, J., Myers, V.S., Gómez, M.V., Crooks, R.M. and Prato, M. (2010) Gold Dendrimer Encapsulated Nanoparticles as Labeling Agents for Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano, 4, 905-912. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn901729d

- 37. Şenel, M. and Nergiz, C. (2012) Development of a Novel Amperometric Glucose Biosensor Based on Copolymer of Pyrrole-PAMAM Dendrimers. Synthetic Metals, 162, 688-694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2012.02.018

- 38. Xu, L., Zhu, Y., Tang, L., Yang, X. and Li, C. (2007) Biosensor Based on Self-Assembling Glucose Oxidase and Dendrimer-Encapsulated Pt Nanoparticles on Carbon Nanotubes for Glucose Detection. Electroanalysis, 19, 717-722. https://doi.org/10.1002/elan.200603805

- 39. Devarakonda, B., Otto, D., Judefeind, A., Hill, R. and Devilliers, M. (2007) Effect of pH on the Solubility and Release of Furosemide from Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) Dendrimer Complexes. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 345, 142-153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.05.039

- 40. Kádár, M., Biró, A., Tóth, K., Vermes, B. and Huszthy, P. (2005) Spectrophotometric Determination of the Dissociation Constants of Crown Ethers with Grafted Acridone Unit in Methanol Based on Benesi-Hildebrand Evaluation. Spectrochimica Acta, Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 62, 1032-1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2005.04.034

- 41. Wang, Y., Rogers, E.I., Belding, S.R. and Compton, R.G. (2010) The Electrochemical Reduction of 1,4-benzoquinone in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium Bis(trifluoro-methane-sulfonyl)-imide, [C2mim] [NTf2]: A Voltammetric Study of the Comproportionation between Benzoquinone and the Benzoquinone Dianion. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 648, 134-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2010.07.016

- 42. Bobrovnik, S. (2002) Ligand-Receptor Interaction. Klotz-Hunston Problem for Two Classes of Binding Sites and Its Solution. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods, 52, 135-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-022X(02)00069-6

- 43. Buczkowski, A., Sekowski, S., Grala, A., Palecz, D., Milowska, K., Urbaniak, P., Gabryelak, T., Piekarski, H. and Palecz, B. (2011) Interaction between PAMAM-NH2 G4 Dendrimer and 5-Fluorouracil in Aqueous Solution. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 408, 266-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.02.014