Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.05 No.06(2015), Article ID:61690,16 pages

10.4236/tel.2015.56081

Predicting Brand Perception for Fast Food Market Entry

Torsten Teichert1*, Tobias Effertz2, Marina Tsoi3, Vladislav Shchekoldin3

1AB Marketing and Innovation, Hamburg University, Hamburg, Germany

2Institute of Business Law, Hamburg University, Hamburg, Germany

3Marketing and Service Department, Novosibirsk State Technical University, Novosibirsk, Russia

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

Received 2 November 2015; accepted 1 December 2015; published 4 December 2015

ABSTRACT

We present a combined and integrative market research approach to address common, but potentially neglected problems resulting from consumers’ perceptions towards food brands. Our findings provide improved response measures and guidance for market entry strategies of established and novel food brands. Two knowledge sources and methods are combined to derive a model of brand perception: experts’ opinions are elicited using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to generate an overall causal effects framework for food brands. Complementary hereto, a survey of potential consumers retrieves consumers’ perceptions regarding market entry scenarios of different food brands. A remote metropolitan area (Novosibirsk) was chosen as quasi-laboratory setting to simulate the market introduction of alternative fast food brands. Insights are gained about the interdependence of branding and advertisement effects. As expected, consumers’ attitudes towards the brand and towards the ad are the key success factors for any type of brand. Different responses depend on consumers’ expectations towards novel or established brands. Otherwise, the paper provides a proof of concept to integrate AHP and experts’ assessments with consumer surveys. Findings indicate a large potential to join external and internal perspectives for obtaining more valid market assessments before the real market entry. Managers might need to enhance their model of assessed consumer perceptions with expert opinion before entering a market in order to align their advertising accordingly. Global and local brands face distinctively different market entry barriers. Novel global brands constitute a promising alternative for a food company wishing to enter a new market. Managers need to decide whether a combined specific approach is necessary and eventually incorporate it in case of new foods brands. A novel method is introduced to assess market perceptions of food brands before the latter actually enter the market. A combined approach incorporates expert opinions to enhance incomplete consumer information. Findings indicate strong interaction effects between brand and advertisement related factors which in turn strongly influence consumers’ perceptions.

Keywords:

Brand, Brand Perception, Brand Cognitions, Attitude towards the Brand, Attitude towards the Ad, Analytic Hierarchy Process, Causal Effects Modelling

1. Introduction

The fast-food market is now more global than ever and its popularity as well as the consumers’ demand for it continue to increase [1] [2] , causing ongoing new product introductions. When introducing novel food products, companies need appropriate knowledge about both the market and relevant marketing stimuli affecting their target audience’s perception in order to conceptualize the overall marketing strategy. Existing research provides a broad theoretical foundation for successfully entering a market. This allows specifying a framework on how the entry of a new brand influences the consumers’ choice and their individual decision-making. However, there may be large differences between perceptions of and preferences for existing and novel brands. Therefore, companies need supplemental information about the consumers’ preferences to assess how to best specify their marketing strategy concerning different types of brands. This might be of utmost importance when entering new markets, which are still subject to growth, product differentiation and changing levels of (consumer) satiation.

Customers usually form their perceptions of fast-food brands through advertising as well as word-of-mouth communication, exposure to promotion (on behalf) of fast-food restaurants, previous personal experience and other sources [3] . Vice versa, fast-food marketing strategies need to be based on a sound a-priori understanding of consumers’ perceptions and their preferences for fast-food outlets. Marketing strategies also need to consider how these factors differ across markets and countries. This constitutes a dilemma for marketing, as market research cannot provide the needed information before market entry. To give an example: Especially adolescents and children are often limited in their ability to articulate their preferences and forecast their reactions to marketing offers [4] . This makes it difficult to assess ex-ante which marketing factors will drive values determining brand perceptions. Thus, it is worthwhile to retrieve the opinions of experts as information complementing traditional market research.

In this paper, we integrate two different approaches of market assessment: Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is used to retrieve a causal effects model from the opinions of experts, whereas consumers’ perceptions are elicited by experimental confrontation with vignettes displaying alternative new product offerings. Combining both methods leads, in our view, to better insights regarding the interplay of branding and advertisement effects on successful market entry. An empirical study is carried out in the Russian fast food market to validate this novel approach. This application case has special practical relevance as well, since the fast food business is rapidly growing as well as a highly lucrative especially in the non-metropolitan areas of BRIC states.

1.1. Relevance of Food Brands

Marketing theory characterizes brands by a broad range of attributes and properties of a trade name, representing value to consumers [5] . Brand concepts typically consist of the following constituent parts: a product or service including all of its attributes; a set of expectations and associations perceived by consumers and assigned to the product or service by them; underlying values of the brand [6] [7] .

Brands emerge over time by (re-)actions both by companies and consumers. The process of brand building is characterized by a differing extent of the participants’ involvement over time: while consumers influence the brand image in the long run, producers and their partners create the initial brand value based on profound and thorough research in market trends, by revealing and addressing characteristics of market demands [8] . The initial positioning of a new brand offering is highly important as consumers are likely to construct their later preferences based on initial experiences of brand and product usage [9] . Thus, both producers and retailers need to carefully follow up developments in preferences for retaining and expanding market shares of each brand.

Many researchers agree that the perception of a food product is affected by many individual factors, such as associated taste, palatability, scent, information from labelling and images, attitudes, memory from previous experience, price, perceiving images, health belief, brand familiarity and loyalty [10] -[12] . Research in the field of food brands focused on how consumers evaluate existing brands―e.g., how customer-based brand equity of food products can be measured [13] , how brands influence the perception of the product quality [14] and how packaging, price and taste are involved in forming a brand preference [15] . Moreover, some studies identified the influence of objective or perceived product quality on the price premium, where a brand can obtain a differentiated position motivating consumers to pay more [12] [16] . In sum, studies so far show that branding is a very critical as well as context-sensitive issue in the marketing of food products.

Vice versa, the fast food market is of special relevance to research on branding because of its global size and growth [2] . Accordingly, consumers’ perceptions of fast food brands have been analyzed from various viewpoints. One stream of research addresses the question of how product information, e.g. nutritional values, influence the brand perception of fast food products [17] . Other research investigated factors influencing the brand perception of fast food outlets by consumers from different countries, such as the USA, India, Malaysia, Pakistanetc [1] [18] [19] . According to previous research focusing on fast food branding [3] [18] [20] , there are two main arguments why a strong brand identity is of key influence for market success: 1) a strong brand image can create a competitive advantage which is more difficult to copy than functional aspects; 2) the brand image reduces the risk of being perceived as a commodity and assist consumers in quickly developing expectations (and preferences) about this brand. Thus, building a well-accepted brand seems to be a key factor for fast food products to successfully enter the market.

1.2. A Model for Brand Building

Advertising is a key marketing instrument to build and strengthen brand perceptions in established and, especially, in new markets. Affective reactions toward commercial stimuli, specifically the “likability” of advertising materials spill over on the brand perception. A widely accepted model of attitude transfer in this regard is the “dual mediation model”, based on Lutz et al. (1983), which includes the following elements outlined below: 1) brand cognitions, 2) attitude towards the ad and 3) attitude towards the brand [21] .

Brand cognitions refer to the customers’ ability to recall and recognize the brand on the market. This concept encompasses brand awareness as well as knowledge about brand elements. Keller (1993) focuses on awareness as the consumers’ ability to identify the brand within its particular product category to the extent sufficient to come to a purchase decision [7] . A broader construct is introduced by Simonion and Ruth (1998) who conceptualize brand familiarity as the combination of awareness and knowledge about the brand [22] .

Attitude towards the brand often embodies the recipients’ affective reactions toward the brand [21] . Brand attitudes are important for the brand concept because they built the basis for consecutive consumer behavior and thereby, as a rule, purchase intention. In practice, a wide range of approaches has been offered to assess brand attitudes. One of the most popular approaches is the expert judgment method based on a multi-attributive model in which brand attitudes are regarded as functions of the attributes and benefits associated with the brand.

Attitude towards the ad is defined as a “predisposition to respond in a favorable or unfavorable manner to a particular advertising stimulus during a particular exposure occasion” [21] . Obviously, when consumers are unfamiliar with an advertised brand, they are more likely to exclusively rely on their attitude toward the advertisement when forming an attitude toward the brand. By contrast, consumers with prior brand familiarity are more likely to draw on their existing brand knowledge so they become rather critical to unfamiliar advertisements of the brand [23] .

The dual mediation hypothesis states that perceptions of an advertisement directly influence the recipients’ attitude towards this ad and indirectly influence both brand cognitions and attitude towards the advertised brand. This model has been empirically tested by various authors in different experiments [24] [25] . An early meta-analysis confirmed the dual-mediation model and indicated an especially large role of the indirect influence of attitudes toward the ad on those toward the brand [26] . Accordingly, this model is widely used, with applications reaching so far as to financial service evaluations [27] or to internet usage [28] .

When applying the dual-mediation model [21] , there obviously are problems in ex-ante separating the specific effects of advertising and those of the brand (i.e. before market entry), because the model requires consumers to first build their attitude based on real-life experiences. Thus, a consumer survey seems inappropriate for disentangling brand-building effects before product market entry in a reliable way. Hence, experts should assess the relative importance of those three elements (brand cognition, attitude towards the ad and attitude towards the brand) for market success of a new brand offering. Following this limitation, we assess the consumers’ specific reactions toward introducing novel fast food offerings. By combining their perceptions with the experts’ view on causal effects of marketing stimuli, we aim to achieve a more reliable estimate of brand building. This will be outlined below.

1.3. Methodological Concept

As shortly outlined above, specific problems arise when forecasting success of new brands in the foods market. In order to address these issues, we assess traditionally used methods of data retrieval, measurement concepts, causal models and estimates. Based on an in-depth assessment of each single step, we derive a methodological concept joining the diverse facets of data retrieval and data analysis in a novel way. This approach addresses the specific requirements of branding research in the food industry.

With the purpose to substantiate findings, we integrate two different methodological approaches toward assessing our specific market: AHP, traditionally used in engineering and innovation management, as well as complex causal modeling, used in advertising and consumer behavior research. The combination of these approaches leads to a hierarchical structure derived top-down, used for assessing the consumers’ brand perceptions which are developed bottom-up. By combining both data sources, it is possible to identify an appropriate model of brand building. This model allows to rank factors influencing the consumers’ brand perceptions and predicting their behavior.

Responses elicited from consumers typically constitute the single referenced data base when empirical models of brand building are derived. The underlying assumption is that consumers have formed pre-defined perceptions and preferences which are largely stable over time. However, the ongoing discourse regarding preference construction [29] clearly stresses limitations to this assumption. Especially for food products, taste preferences may easily develop, and hence change, over time. This makes predicting the possible success of new products potentially erroneous, as these predictions are solely based on the consumers’ ex-ante assessments of the product. Thus, it is reasonable to limit the reliance on consumers’ ex-ante assessments as the main data base for brand building models.

Traditional market research techniques lead us to expecting consumers’ articulated perceptions of product features to be more reliable, shared and stable than the consumers’ preference evaluations of the corresponding marketing stimuli. This is e.g. the leading premise of the most widely applied market research method: conjoint analysis [30] . Consequently, we only utilize consumers’ perceptions when assessing new fast food offerings. We then utilize judgments on behalf of experts to reveal the hierarchical structure of latent constructs. Here, we make use of the fact that experts have a “gut-feeling” concerning marketing measures and their effectiveness due to their personal experience in the field. Joining both sub models, we empirically investigate relations of cause and effect for novel food brands.

Regarding the data collection technique, traditional questionnaires are sometimes restricted in reliably assessing the consumers’ holistic perceptions and feelings concerning food products. This is most certainly the case for prospective measures focusing on novel food brands, where respondents need to cognitively understand and imaginatively feel the aspired future brand setting [31] . Especially children provide unreliable and biased self- reports [32] . To limit distortion due to lack of understanding and other biases, we apply an alternative approach of data collection by using the vignette technique. Vignettes are short descriptions of a social situation containing precise references to those factors thought to be the most important ones in the respondents’ judgment- making processes [33] . Vignettes have been used to study attitudes, perceptions, beliefs and norms of individuals [31] , especially if participants lack personal experience and knowledge of the storyline behind the considered product. Vignettes are particularly suited to assess understandings and perceptions, as they focus on how respondents think, feel and act in the depicted situation [33] .

Concerning the measurement model, brand effect studies typically utilize reflective measures to assess latent constructs as e.g. attitude or (purchase) intention measures. Hereby, correlation measures are used to infer about the existence and the extent of item-encompassing latent constructs. This measurement approach still prevails― despite conceptual evidence that many marketing constructs are better modeled as formative constructs [34] -[36] . The main difference between both measurement approaches is the requirement of a simultaneous presence of all indicators for reflective measures, while formative measures allow trade-offs between or even the absence of single indicators [37] [38] . To give a simple example, you do not need to drink a few liters of beer as well as wine at the same time to achieve a latent state of drunkenness―one of them will suffice. Unfortunately, formative measures require a solid conceptual framework, ensuring that all theoretically derived relevant “forming” indicators are included [39] .

Exploratory factor analysis is a commonly applied method of reflective measurement models. It allows for singling out so-called latent factors as it defines the behavior of the factors of interest by studying the combination of initial factors based on determination of equivalence classes [40] . For instance, a successful application of the factor analysis by the authors of this paper allowed revealing actual reasons behind the students’ behavior when choosing a higher education institution [41] . However, factor analysis can cause quite a number of difficulties. Accordingly, one could come across the problem of implausibility when using factor analysis prior to experience gained through consumption.

Formative models require a different measurement process. Our approach is based on the application of expert judgments employing the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), a prominent approach when analyzing decision-making with multiple factors and optimality criteria. AHP as a comprehensive approach is characterized by three basic functions―structuring the complexity, measuring the experts’ opinions and synthesizing them.

Concerning the specification of a testable causal model, a wide variety of approaches exist to test the aforementioned model of brand building [6] [21] [23] [25] . These approaches typically utilize evaluations of advertisements as explaining factors in a causal model, entailing brand assessments and purchase intention as dependent variables. Lutz et al. (1983) developed and tested alternative models relating advertisement and brand effects with purchase behavior. While they favored the “Dual Mediation Hypothesis”, they also considered alternative frameworks as the “Modified Affect Transfer Hypothesis”, the “Reciprocal Mediation Hypothesis” or finally, the “Independent Influence Hypothesis” which assumes independent influences of both “attitude towards the ad” and “attitude towards the brand” on purchase intention.

This controversial discourse about the suitable specification of a dual-mediation framework has not been settled yet (see e.g. applications of Karson and Fischer [42] [43] ). Most of all, the fundamental issue of endogeneity could not be finally resolved due to the inherent interdependence between advertisement and brand stimuli. However, from a managerial perspective, the specifications of the causal paths are not as relevant as obtaining reliable predictions regarding future consumer behavior. Managers are concerned about the total effects resulting from aggregating both indirect and direct effects. Accordingly, an all-in-one causal model jointly considering all effects of marketing measures on response behavior seems sufficient for the purpose of assessing whether a market entry might be successful or not. Thus, we choose multivariate regression analysis as a robust method of analysis. From it, we derive elasticity coefficients in order to simplify economic conclusions.

To sum up, features of commonly used methods and of our suggested combined approach are summarized and contrasted in Table 1.

1.4. Russian Fast Food Market

Rapidly developing markets are particularly interesting when investigating problems regarding the market entry of new brands because these markets are not satiated yet with branded products. e.g. in 2013, the fast food market in Russia was one of the main growth engines in foodservice and it continued to grow in 2014 [2] . Such a strong development is caused, in large part, by the overall growing popularity of franchising in Russia, making the latter one of the main tools of fast food business development. Today, the fast food segment is most popular with young Russian consumers who make up more than 54% of the fast food restaurants visitors [2] .

According to expert estimates, the share of foreign brands within the Russian fast food market is about 40%. American fast foods formats, such as Subway, McDonald’s, Burger King, KFC and Baskin-Robbins, dominate in Russia. Almost 3800 chain restaurants belong to approximately one hundred different fast food brands. Almost half (44%) of all fast food restaurants are concentrated in Moscow and St. Petersburg whereas only 12% of

Table 1. Comparison of features and characteristics of commonly used and suggested approaches.

the total population lives in these cities. Accordingly, 56% of all fast-food restaurants serve about 88% of the Russian population [2] . In this context, the relatively high level of competition in Moscow and St. Petersburg pushes many franchisers to more actively open fast food restaurants in other regions, especially in cities with more than one million inhabitants (like Novosibirsk, Nizhniy Novgorod, Rostovetc).

Novosibirsk is the third largest city of the Russian Federation with a population of 1.67 million as of 2014. Novosibirsk is located in the center of the country, in South-West Siberia. It is well-known as one of the biggest industrial, cultural and scientific centers of the Russian Federation. It may be considered as representing a typical larger Russian city―with the exception of Moscow and St. Petersburg as these two are distinctively different from other Russian cities in the salary level and living standards. International franchisers started to do business in Novosibirsk; they already operate more than 85 fast food restaurants there. Currently, global, national and local brands compete in the fast food market in Novosibirsk. Among these brands are Burger King, Subway, KFC, Papa John’s Pizza etc. as well as the national brands Kroshka-Kartoshka (potato), Russian Bliny (pancakes), Teremok etc. while also local brands, like Uncle Dener (kebab) and Podoroghnik (burgers) develop. In this regard, Novosibirsk seems an appropriate place for studying consumer behavior both from a regional point of view and to prototypically describe the situation of the entire country.

In value terms, McDonald’s is the leader of the Russian fast food market with annual sales of about $2.2 billion in 2013, accounting for 8% of its worldwide sales [2] . McDonald’s entered the Russian market in 1990 and has opened 414 fast-food restaurants in 60 cities of Russia until the end of 2014. It opened its first restaurant in Novosibirsk in 2014, after our empirical study was conducted. McDonald’s corporation chose Siberia, in particular Novosibirsk, as one of its main development areas and planned to open 10 more fast-food restaurants spread all over the city of Novosibirsk. Also direct competitors of McDonald’s are interested in the Ural and West Siberian markets [44] . For instance, Burger King entered the Novosibirsk market already in 2013 and will open additional eating facilities until the end of 2015.

Despite the dynamics displayed above, the Russian market is not fully developed yet. Some global fast food brands are unknown to Russians, but the latter “learn” quickly. However, there is a less fortunate example such as Baskin-Robbins, which initially opened more than 10 outlets around the city, but was forced to close most of them within 3 years as it failed to gain an appropriate recognition by Siberian consumers. Clearly, such a situation highlights the importance of identifying and studying consumers’ perceptions towards and preferences regarding fast food brands.

1.5. Children as Target Customers

Young consumers are frequent visitors of fast food restaurants and they reply more readily and positively to marketing incentives than adults [45] . Furthermore, branding seems quite important to this target group as they attribute their satisfaction more to the brand than to the quality of the consumed product [46] . Besides being an attractive, progressive and profitable target group, children tend to become long-term consumers. They start to make purchases with their pocket money while they are otherwise still influenced by their parents’ consumption decisions, and, finally, when growing up, they become consumers in their own right. Here, they frequently remain loyal to the brands they remember in one way or another from their childhood [4] [45] .

Research in children marketing indicates that young consumers start recognizing brands from an early age [47] and that the product bearing a brand’s logo leads to more enthusiasm on their behalf than a no-name product [46] . Furthermore, children readily respond to advertising messages and evaluate them less critically than adults because they have not yet developed the advertising knowledge and cognitive skills necessary to cope effectively with advertising messages [4] . In the same vein, young consumers may not be as competent to answer hypothetical and theoretical questions about marketing instruments and stimuli because of different cognitive capacities. Thus, there is a need to disentangle perceptions from assessments when conducting market research for novel products aimed at children.

2. Setup of Empirical Study

2.1. Sample

A research team supervised by the authors conducted a survey with children aged 10 to 17 years attending Novosibirsk schools. To select the respondents, a multi-level cluster sampling technique was implemented: Novosibirsk schools to participate in the study were chosen at random; herein, classes were randomly selected. Experiments were conducted during class time with all children present. They were confronted with one specific vignette. 778 students of secondary general education institutions took part in the survey. The distribution of the sample target audience by age cohorts was as following: 35% of the cohorts were 5th to 6th grades, 32% were 7th to 9th grades and the 10th- to 11th grades accounted for 33%. Data checks found only few questionnaires to be answered either incorrectly or only in parts. After excluding unreliable answers, 729 of the initial 778 questionnaires (97.3%) were retained as data basis.

2.2. Vignettes Used for Revealing Consumers’ Perceptions

The vignette technique was used to assess the brand perception by customers through analyzing given advertising images. Vignettes consisted of all typical elements of print advertisements: a logo, a visual as well as a slogan. To ensure that context did not matter, different respondents were offered identical advertising images depicting only different logo options for each brand.

We chose McDonald’s as a popular worldwide brand which is affordable for most consumer groups to convey a high degree of relevance to the study. McDonald’s is the brand studied most frequently―not only because of its prevalence [1] [19] [20] , but also due to its background as the world’s major fast food advertiser. Thus, we compared McDonalds with two types of (hypothetical) novel brands: an imaginary novel global brand “FastyJu” and an imaginary novel local brand “Тинар” (Tinar), the latter written in Cyrillic alphabet. The names for hypothetical novel brands were developed and tested as the results of three focus-groups with children and teenagers. Examples of advertising images and logos used in the survey are shown in Figure 1.

In every school class, the logo of only one of three brands was displayed and its image assessed. A similar approach was recommended by Achenreiner and John [46] . It ensures that children did not directly compare brands but focused on the single stimulus provided. If we had displayed all three brands at once, the McDonald’s estimates would have significantly exceeded the attention level as it is already know. This approach would not have allowed the revelation of the children’s actual attitude towards different logos and brand images.

The stimuli were selected based on an experimental design plan balancing stimulus confrontation across different schools and classes. This procedure enabled an equal distribution of answers among the three vignette types. Some differences could be observed in the distribution of the brands studied among the respondents since the number of students varied in the investigated school classes: McDonald’s (30.3%), Tinar (30.3%) and FastyJu (39.4%).

2.3. Measuring Consumers’ Perceptions of the Vignettes

A self-reporting questionnaire contained 27 questions and was based on a five-point Likert-scale structure and a semantic differential in which respondents were asked to describe their perceptions of the three different brands. The construction of both the questionnaire and the items therein followed previous models and recommendations,

Figure 1. Logos and advertising images of global and local fast food brands.

primarily those prevalent within the field of brand equity [6] [7] .

The brand cognition scale was taken from Simonion and Ruth [22] . It includes the three facets brand recognition, brand recall and brand’s past purchase or use. This approach resembles the idea of Lutz et al. [21] who stress the cognitive components as initiators of the dual-mediation hypothesis. Thus, we refer to brand familiarity to combine both perspectives, namely awareness and knowledge about the brand.

For assessing the brand advertising effect, we used the persuasive disclosure inventory (ad-viewers judgment of advertising) introduced by Feltham [48] . It is represented by the following factors: ethos, logos and pathos. “Ethos” refers to persuasive appeals concentrating rather on the source than on the message; “logos” stands for information about a concept which a consumer forms based on (personal) belief; “pathos” describes emotional or affective appeal.

For measuring attitude towards the brand, we applied a 7-point scale developed by Shamdasani et al. [49] , used to assess both products and brands. Brand attitudes were decomposed into the following subdimensions: emotional perception of the brand, attractiveness of the brand and approval of the brand.

To assess the brand perception, we used a classification of product benefits including functional, emotional and self-expressive categories [6] . The functional benefits are based on a product attribute providing the customer with functional utility. Emotional benefits are positive feelings that consumers perceive upon product consumption, while self-expressive benefits represent the product’s ability to communicate the user’s self-image through its consumption. The connection between brands and customers is strengthened by focusing on aspects linked to their personality [6] . Purchase intention then depends on whether the product benefits, which are perceived to be associated with consumption, exceed the expectations of the potential consumers [11] . Thus, the customers’ assessment of product benefits is derived from a hierarchical structure defined by the following second-level factors: utilitarian product benefits, emotional product benefits and self-expressive product benefits. The 7-point scale developed by Shamdasani et al. [49] was again used for this assessment.

Finally, we had to utilize the latent construct “brand perception” as dependent variable―instead of real purchases―since our product is hypothetical and not available on the market. Stated purchase intentions might be not reliable since fast food consumption is not characterized by planned purchases but rather impulsive purchase behavior. The latter might even be stronger when children are the target audience.

2.4. Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process to Retrieve a Causal Effects Model

The second part of our combined approach uses the “Analytic Hierarchy Process” (AHP) developed by Saaty [50] . AHP is a structured process decomposing complex multivariate assessments by revealing and testing a hierarchical problem structure. Weighting information is derived as a result. AHP disentangles complex assessments via matrix algebra and, thus, provides a robust basis for obtaining reliable answers from experts. It has been widely used in industry, medicine, scientific research, management, marketing and other fields due to its universality and relative simplicity [50] .

A core benefit of AHP is its well structured process: first, the main factors (characteristics) exhaustively describing the studied objects or processes have to be determined. A hierarchical system is then developed, allowing to combine factors to obtain higher-level factors. For the whole factor set, experts are asked to compare pairs of these factors based on Saaty’s 9-point scale. The experts’ quantitative judgments are used to calculate weighting coefficients determining the importance of each of the factors and their ranking in the whole hierarchical structure. Finally, an analytical expression is specified to calculate generalized values.

In contrast to the highly sophisticated setup and evaluation scheme, the AHP method is based on simple pairwise comparisons and, thus, reduces the burden on interviewed experts: When making paired comparisons, the experts express judgments about the relative importance of each of the two factors. Hereby, AHP uses a special scale allowing to calculate relative weights as well as to execute sophisticated reliability tests.

Let us consider an example for calculating values of relative importance (weighting coefficients) of factors within the/our hierarchical structure. Every part of the hierarchical structure is analogously built as this process is repeated for each of them.

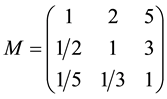

The experts are asked to evaluate the pairwise importance of factors X11―brand recognition, X12―brand recall, X13―past purchase or use of the brand when assessing the factor value X1 (brand cognitions). They might conclude that:

1) X11:X12 = 2:1, that is, the experts have doubts whether the brand recognition is of the same importance as brand recall or some more important than the latter in terms of the complex factor “brand cognitions”.

2) X11:X13 = 5:1, that is, according to experts, brand recognition is of more importance than the brand’s past purchase or use.

3) X12:X13 = 3:1, that is, the experts regard the brand recall is some more important than the brand’s past purchase or use.

In compliance with the AHP, a pairwise comparison matrix is composed in order to calculate the weights of factors X11, X12, and X13 in the form

.

.

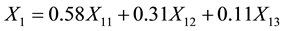

By calculating the eigenvector of the matrix which corresponds to its maximum eigenvalue and normalizing it, we obtain the factor weight vector [50] . These weights provide the values of X1 as a linear combination of the three second-level factors:

.

.

In this case, experts think that brand cognitions are mainly influenced by recognition of the brand (weight 0.58), followed by brand recall (weight 0.31), while past purchases of the brands are perceived to exert only minor influence on the consumers’ brand cognitions (weight 0.11).

3. Results and Discussion

The results are presented in a three-step approach: 1) the hierarchical structure for the main factors influencing brand perception according to the experts’ judgments is developed; 2) the factor distribution for different types of brands is analyzed and 3) the multiple linear regression model of brand perception and the factors influencing consumers reactions are estimated based on elasticity calculations.

3.1. Hierarchical Structure of Factors

AHP is used to construct a causal effects model of brand perception. For the empirical example presented here, 11 experts―specialists in the field of marketing and representatives of fast food market leader companies― were selected. They were interviewed personally in order to gain the pairwise comparisons needed to execute AHP. In a first evaluation step, the degree of consistency of the experts’ judgments is assessed by means of AHP’s Consistency Ratio (CR). Inconsistencies in judgments of experts are considered to be acceptable as soon as CR ≤ 0.1 [50] . As shown in Table 2 (left column), all values are well below the threshold value, indicating a high reliability and consistency of the experts’ assessments. Thus, this data can be used to build a hierarchical brand assessment model.

The final form of the factor structure is shown in Table 2. The expressed values represent the importance of each of the structure elements for the factor in the next level of the hierarchy.

Already at this stage, several insights can be gained from analyzing the experts’ assessments with AHP: According to this analysis, brand cognition of fast food brands is mainly driven by recognition effects (Saaty’s weight 0.58). This is in line with our expectations since fast food brands are low-involvement products where learning occurs more passively, e.g. by the “mere exposure effect” [51] . Experts judge advertising ethos to be primarily influenced by the credibility of the ad (0.54), whereas they consider reliability to be a quite unimportant issue (0.16). In line with our expectations, consistency (0.65) and information value (0.23) load particularly high on the perception of the advertised logo. As a concept, pathos by itself is primarily based on emotional response (0.59) but influenced by targeting and motivational issues as well. Finally, the attitude towards the brand reveals to be equally influenced by many facets, whereas product benefits are primarily obtained through utilitarian benefits (0.57).

3.2. Perceptions of Consumers

The consumers’ elicited perceptions about each construct complement the structural information provided by experts. Before joining both views in an overall model of brand building, we first provide descriptive information

Table 2. Hierarchical structure for estimating brand perception.

about childrens’ perceptions aggregated into the highest-level constructs of “brand cognitions” (X1), “attitude towards the ad” (X2) and, finally, “attitude towards the brand” (X3), depending on the type of brand investigated.

Figure 2 presents histograms of the derived factor values (rounded in full numbers) where the left histogram corresponds to the global brand (McDonald’s), the right one to the novel local brand (Tinar), and the histogram in the middle refers to the novel global brand (FastyJu). The same sequence is retained when analyzing the rest of the factor distributions.

Comparisons of the histograms show that the distributions of “brand perceptions” are not identical for the various types of brands. As expected, the vast majority of the respondents seems to be well-informed about McDonald’s as a brand, a situation vastly different to those vis-à-vis the novel brands (Figure 2(a)). Although both the new global brand and new local brands are, by definition, objectively unfamiliar to the respondents, many of them nonetheless indicated (even with certainty) to have brand cognitions about the novel global brand. Only about 20% of the respondents acknowledged their complete lack of awareness about this (non-existing) brand. This cognition bias can be explained by the fact that children and teenagers try to appear more competent than they really are, which might have led to overstating brand awareness. A similar trend can be observed for all the remaining factors. Evidently, when having demonstrated high brand awareness, a child adheres to the chosen line of behavior: trying to endow the novel brand with certain properties and relate it to popular brands (their logos, advertisement etc.).

Concerning the attitude towards the ad (Figure 2(b)), there are as well major differences between the distributions: the advertising impression towards the widely known brand McDonald’s is bell-shaped. This is not the case for the novel global brand FastyJu. It is possible that children faced difficulties in formalizing their ideas and impressions when answering questions about the advertisement of the unfamiliar brand FastyJu. Hence, the respondents seemed to jump from one extreme evaluation to another/the other one. Regarding the new local fast-food brand, the distribution is more similar to the global brand. This may indicate that children, for the most part, are highly receptive towards a local producer’s brand. The latter’s products are generally expected to be more affordable. In the left part of the histogram, one may notice this second maximum (value is equal to 1). This means that approximately 20% of the respondents lacked attitude towards the brand ad, most probably as they were uncertain about the suggested brand Tinar.

Figure 2. Distribution of factors values. (a) Distribution of brand cognitions values; (b) Distribution of values of attitude towards ad; (c) Distribution of attitude toward the brand values.

The distribution of attitudes towards the brand (Figure 2(c)) reveals several peaks in the distributions. The largest peaks occur at the factors value of 4 (which means neither positive nor negative attitude towards the brand). This is in line with no previous experiences being present. However, high values for “attitude towards the brand” can be observed for the global brand. Since McDonald’s is well-known and popular, this is a logical effect―although the chain entered the Novosibirsk market after this study was finished. Besides, the histograms of McDonald’s and FastyJu histograms are highly similar. This leads us to assume that unknown global brands might profit from positive attitudes toward the fast food market. Thus, global brands could probably be quite successfully introduced into emerging fast-food markets. FastyJu is regarded by children as a brand belonging to this very class of global brands. Thus, their process of building an attitude toward the new brand may be similar to the process of attitude towards an existing global fast-food brand, including McDonald’s.

Although these findings are purely descriptive patterns, they lead to the conclusion that brand building has to take into account both the context as well as the dynamics of subjective perceptions.

3.3. Elasticity Coefficients in the Combined Model

Data from the childrens’ survey data was used for constructing and identifying the model for brand perception estimation. As a first step, a correlation analysis was executed to reveal pairwise connections between the factors X1, X2 and X3 and their effect on the response value Y, i.e. brand perception. High values for the pairwise correlation coefficients of 0.439, 0.648 and 0.673, respectively, as well as strong Student’s t-test indicate linear relationships of different strength [52] . Accordingly, the extent of the children’s brand perception seems to be defined less by the values of brand cognitions than by the attitude toward the brand and the attitude towards the ad.

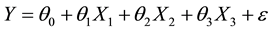

The next step in our research was to construct and identify a multiple linear regression model in the form

, (1)

, (1)

where

are unknown parameters to be estimated, while

are unknown parameters to be estimated, while

is the model random error according to chosen regression analysis standard assumptions (about zero expectation, homoscedasticity and lack of autocorrelation) [52] .

is the model random error according to chosen regression analysis standard assumptions (about zero expectation, homoscedasticity and lack of autocorrelation) [52] .

The results of the multivariate regression on basis of the opinions of experts (“combined approach”) are shown in Table 3(a), the “regular” regression results obtained by just assessing the children’s attitudes are given in Table 3(b). The model parameters estimators and coefficients of determination are shown, probabilities of rejecting hypotheses of parameter and model significance are stated in brackets (the levels of significance achieved when testing hypotheses by Student’s t-test and Fisher’s F-test respectively), or it is noted that the parameter proved to be insignificant, i.e. the appropriate hypothesis is not rejected [52] .

When comparing the results, the combined approach yields quite similar results to the “uninformed” model for the real global brand, although with slightly different estimators for

and

and

In all three cases, it can as well be observed that the parameter corresponding to “brand cognitions” is the least significant, which indicates a lower influence of this factor on the consumers’ brand perception. Moreover,

Table 3. (a) Results of estimation of the combined brand perception model; (b) Results of estimation of the brand perception model without AHP information.

this parameter estimator value is diametral different for novel local brands. In this case, a negative value of parameter

When applying models similar to (1), an opportunity of ranking factors according to their influence on the response is of great importance. There are dozens of ranking methods; in this paper, we make use of the elasticity coefficient apparatus to solve this problem. The elasticity coefficient (averaged over the sample) is defined as

where

Looking at the elasticity coefficients for the global fast food brand, two out of the three brand building measures stand out: factors X2 and X3 are of equal importance for increasing (the extent of) brand perception, while the influence of factor X1 appears to be only half as large. This, again, shows that “attitude towards the ad” is as important as “attitude towards the brand” for consumers’ reactions toward an established global brand.

A different situation arises when novel brands are analyzed. Here, the attitude towards the ad exerts a much greater influence on the consumers’ reaction. Since attitudes towards a brand cannot be developed a priori, this is reasonable. However, the diminishing effect is even stronger for brand cognitions (factor X1), exhibiting even a reversed sign in case of the novel local brand: Here, the extent of novel global brand’s perception slightly decreases (by 6.849%) when the children’s brand cognitions increase. This shows the extent to which the initial goodwill wears off once the consumers build up brand cognitions toward the local brand. The expectancy- confirmation framework might provide an explanation for such a negative consequence. The consumers’ purchase decision is associated with their perception and their expectations toward the brand [7] . If the perception of a product exceeds the consumers’ expectations, the consumer’ will have positive feelings and a high intention to purchase.

Regarding factors X2 and X3 for the novel global brand, the influence of the consumers’ impression of the brand ad is half the influence of attitude toward the brand. Comparing the novel global brand to the local one, the ratio of the influences changes―the consumers’ impression of attitude via brand advertising is still more significant, but the difference reduces to 25% relative to the extent of attitude toward the brand. Thus, we may conclude that to increase the children’s brand perception, the producers or brand owners will try to strengthen the impression of advertising on children which is created by the hierarchical structure factors shown in Table 3. Also, it should be remembered that the attitude toward the brand is of considerable importance, where the emotional perception and the correspondence of the brand logo to the consumer perception of an ideal fast food are essential components.

4. Conclusion and Implications

Finally as a result of research made we may state that the joint application of two different approaches for market assessment―AHP, traditionally used in engineering and innovation, and estimates regarding the consumers’ perception of the brand―let us conclude that attitudes towards the brand and attitude towards its ad are highly important factors for the consumers’ perception formation toward any popular brand.

The study revealed significant differences in the consumers’ perception of various types of brands. In case of the new global brand presented in the study, the consumers have even identified a non-existent brand by stating

Table 4. Values of the elasticity coefficients.

they “have recognized, have heard about it before”. Believing that this brand exists, they imparted their impression regarding the advertising based on brand name, logo and advertisement appeal. When thinking about entering a new fast food market, brand owners may, as a rule, select one of the following alternatives: either buy a franchise of an already well-known popular brand (e.g. McDonald’s, KFC, Burger King) or market goods under the original name. In many cases, the first alternative proves too expensive for Russian businessmen since buying a franchise requires fulfilling a whole set of business environment conditions. The advantage of franchising is that the brand’s wide popularity promotes success when entering local markets even though the majority of consumers (young people) might not have any first-hand experience of interacting with the brand.

When entering a market with one’s own brand, owners will face different challenges which are highlighted by our research. Firstly, with an increasing level of local brand cognitions (e.g. the brand name written in Cyrillic), brands may face a decrease of the consumers’ level of brand perception. Thus, attention has to be paid to not forego initial goodwill of consumers. Secondly, when promoting a new brand as global (e.g. with its name written in Latin), a considerable part of the consumers might perceive the brand as a familiar one and transfer their previous experiences of interacting with similar (but not identical) fast food brands to this new one. This transfer of brand perceptions can provide a leapfrogging advantage for a novel brand if it is considered to be global. For instance when the Carl’s Jr. Corporation entered the Novosibirsk market with a new and previously unknown brand in 2011, it was accepted very quickly by consumers despite its high prices for burgers. This may be due to the fact that consumers perceived the brand to be famous while unknown to them. However, marketers need to be aware of the fact that such a transfer of perceptions can have both positive as well negative effects for the new brand as both positive and negative impressions might be transferred to the (previously) unknown brand.

Finally, young consumers frequently choose well-known brands, e.g., due to mass media or the advice of friends. The finding that brand awareness was less influential than the attitude toward the brand by logo and attitude via brand advertising may be explained by the fact that McDonald’s had not yet started business in Novosibirsk at the time of the survey. Notwithstanding, the children promptly identified it thanks to active advertising support given by mass media, in particular, by TV.

Cite this paper

TorstenTeichert,TobiasEffertz,MarinaTsoi,VladislavShchekoldin, (2015) Predicting Brand Perception for Fast Food Market Entry. Theoretical Economics Letters,05,697-712. doi: 10.4236/tel.2015.56081

References

- 1. Goyal, A. and Singh, N.P. (2007) Consumer Perception about Fast Food in India: An Exploratory Study. British Food Journal, 109, 182-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070700710725536

- 2. Hansen, E.W. (2014) Fast Food Sector Keeps Expanding as Economy Cools. Report, Moscow ATO Russian Federation, Moscow.

- 3. Kara, A., Kaynak, E. and Kucukemiroglu, O. (1997) Marketing Strategies for Fast Food Restaurants: A Customer View. British Food Journal, 99, 318-324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070709710194014

- 4. Connell, P.M., Brucks, M. and Nielsen, J.H. (2014) How Childhood Advertising Exposure Can Create Biased Product Evaluations That Persist into Adulthood. Journal of Consumer Research, 41, 119-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/675218

- 5. Armstrong, G. and Kotler, Ph. (2005) Marketing: An Introduce. Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River.

- 6. Aaker, D.A. (1996) Measuring Brand Equity across Products and Markets. California Management Review, 38, 102-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/41165845

- 7. Keller, K.L. (1993) Conceptualizing, Measuring, Managing Customer Based Brand Equity. Journal of Marketing, 57, 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1252054

- 8. Kwun, D. and Oh, H. (2007) Consumer’ Evaluation of Brand Portfolios. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26, 81-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.09.003

- 9. Rosa, J.A. and Spanjol, J. (2005) Micro-Level Product-Market Dynamics: Shared Knowledge and Its Relationship to Market Development. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33, 197-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0092070304269839

- 10. Imram, N. (1999) The Role of Visual Cues in Consumer Perception and Acceptance of a Food Product. Nutrition & Food Science, 99, 224-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00346659910277650

- 11. Tikkanen, I. and Vaariskoski, M. (2010) Attributes and Benefits of Branded Bread: Case Artesaani. British Food Journal, 112, 1033-1043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070701011074381

- 12. Anselmsson, J. and Bondesson, N.L.A. (2013) What Successful Branding Looks Like: A Managerial Perspective. British Food Journal, 115, 1612-1627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2012-0021

- 13. Rajh, E., Vranesevic, T. and Tolic, D. (2003) Croatian Food Industry—Brand Equity in Selected Product Categories. British Food Journal, 105, 263-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070700310477059

- 14. Sanzo, M.J., Beléndel Río, A., Iglesias, V. and Vázquez, R. (2003) Attitude and Satisfaction in a Traditional Food Product. British Food Journal, 105, 771-790. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070700310511807

- 15. Méndez, J.L., Oubina, J. and Rubio, N. (2011) The Relative Importance of Brand-Packaging, Price and Taste in Affecting Brand Preferences. British Food Journal, 113, 1229-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070701111177665

- 16. Anselmsson, J., Bondesson, N.V. and Johansson, U. (2014) Brand Image and Customers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Food Brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23, 90-102.

- 17. Davies, G.F. and Smith, J.L. (2004) Fast Food: Dietary Perspectives. Nutrition & Food Science, 34, 80-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00346650410529050

- 18. Ehsan, U. (2012) Factors Important for the Selection of Fast Food Restaurants: An Empirical Study across Three Cities of Pakistan. British Food Journal, 114, 1251-1264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070701211258808

- 19. Mohamed, R.N. and Daud, N.M. (2012) The Impact of Religious Sensitivity on Brand Trust, Equity and Values of Fast Food Industry in Malaysia. Business Strategy Series, 13, 21-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17515631211194599

- 20. Vignali, C. (2001) McDonald’s: “Think Global, Act Local”—The Marketing Mix. British Food Journal, 103, 97-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00070700110383154

- 21. Lutz, R.J., MacKenzie, S.B. and Belch, G.E. (1983) Attitude toward the Ad as a Mediator of Advertising Effectiveness: Determinants and Consequences. Consumer Research, 10, 532-539.

- 22. Simonin, B.L. and Ruth, J.A. (1998) Is a Company Known by the Company It Keeps? Assessing the Spillover Effects of Brand Alliances on Consumer Brand Attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 35, 30-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3151928

- 23. Keller, K.L. (2001) Building Customer-Based Brand Equity. Marketing Management, 10, 14-21.

- 24. Lutz, R.J. and MacKenzie, S.B. (1989) An Empirical Examination of the Structural Antecedents of Attitude toward the Ad in an Advertising Pretesting Context. Journal of Marketing, 53, 48-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251413

- 25. Miniard, P.W., Bhatla, S. and Rose, R.L. (1990) On the Formation and Relationship of Ad and Brand Attitudes: An Experimental and Causal Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 27, 290-303. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3172587

- 26. Brown, S.P. and Stayman, D.M. (1992) Antecedents and Consequences of Attitude toward the Ad: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 34-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209284

- 27. Foroudi, P., Melewar, T.C. and Gupta, S. (2014) Linking Corporate Logo, Corporate Image, and Reputation: An Examination of Consumer Perceptions in the Financial Setting. Journal of Business Research, 67, 2269-2281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.015

- 28. Ko, H., Cho, C.-H. and Roberts, M. (2005) Internet Uses and Gratifications. Journal of Advertising, 34, 57-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639191

- 29. Payne, J.W., Bettman, J.R. and Schkade, D.A. (1999) Measuring Constructed Preferences: Towards a Building Code. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19, 243-270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1007843931054

- 30. Teichert, T. and Shehu, E. (2010) Investigating Research Streams of Conjoint Analysis: A Bibliometric Study. Business Research, 3, 49-68.

- 31. Finch, J. (1987) The Vignette Technique in Survey Research. Sociology, 21, 105-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038587021001008

- 32. O’Dell, L., Crafter, S., de Abreu, G. and Cline, T. (2012) The Problem of Interpretation in Vignette Methodology in Research with Young People. Qualitative Research, 12, 702-714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468794112439003

- 33. Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2013) Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. SAGE Publication, London.

- 34. Jarvis, C.B., MacKenzie, S.B. and Podsakoff, P.M. (2003) A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 199-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/376806

- 35. Fassot, G. (2006) Operationalisierung latenter Variablen in Strukturgleichungsmodellen: Eine Standortbestimmung. Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 58, 67-88.

- 36. Podsakoff, N.P., Shen, W. and Podsakoff, P.M. (2006) The Role of Formative Measurement Models in Strategic Management Research: Review, Critique, and Implications for Future Research. Research Methods in Strategy and Management, 3, 201-256.

- 37. Bollen, K.A. (1989) Structural Equations with Latent Variables. Wiley, New York.

- 38. Bollen, K.A. and Lennox, R. (1991) Conventional Wisdom on Measurement: A Structural Equation Perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 305-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305

- 39. Diamantopoulos, A. (2011) Incorporating Formative Measures into Covariance-Based Structural Equation Models. MIS Quarterly, 35, 335-358.

- 40. Kim, J.-O. and Mueller, C.W. (1986) Factor Analysis: Statistical Methods and Practical Issues. Sage Publications, Newbury Park.

- 41. Shchekoldin, V. and Tsoy, M. (2010) The Factor Analysis for the Education Market. Marketing, 5, 97-105. (In Russian)

- 42. Karson, E.J. and Fisher, R.J. (2005) Reexamining and Extending the Dual Mediation Hypothesis in an On-Line Advertising Context. Psychology & Marketing, 22, 333-351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mar.20062

- 43. Kempf, D.S. and Smith, R.E. (1998) Consumer Processing of Product Trial and the Influence of Prior Advertising: A Structural Modeling Approach. Journal of Marketing Research, 35, 325-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3152031

- 44. Kramer, A.E. (2011) Russia Becomes a Magnet for US Fast-Food Chains. New York Times, 3 August.

- 45. McNeal, J.U. (1992) Kids as Consumers: A Handbook of Marketing to Children. Lexington Books, New York.

- 46. Achenreiner, G.B. and John, D.R. (2003) The Meaning of Brand Names to Children: A Develop-Mental Investigation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13, 205-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_03

- 47. Robinson, T.N., Borzekowski, D.L., Matheson, D.M. and Kraeme, H.C. (2007) Effects of Fast Food Branding on Young Children’s Taste Preferences. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161, 792-797. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.8.792

- 48. Feltham, T. (1994) Judgment of Ads Viewer Judgment of Ads: The Persuasive Disclosure Inventory. In: Bearden, W.O. and Netemeyer, R.G., Eds., Handbook of Marketing Scales: Multi-Item Measures for Marketing and Consumer Behavior Research, 2nd Edition, Sage Publication, Newbury Park, 289-290.

- 49. Shamdasani, P.N., Stanaland, A.J.S. and Tan, J. (2001) Location, Location, Location: Insights for Advertising Placement on the Web. Journal of Advertising Research, 41, 7-21.

- 50. Saaty, T.L. (1980) The Analytic Hierarchy Process. McGraw Hill International, New York.

- 51. Hawkins, S.A. and Hoch, S.J. (1992) Low-Involvement Learning: Memory without Evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 212-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209297

- 52. Shchekoldin, V., Timofeev, V. and Faddeenkov, A. (2013) Econometrics. URAIT, Moscow. (In Russian)

NOTES

*Corresponding author.