American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Vol.06 No.05(2016), Article ID:66405,10 pages

10.4236/ajibm.2016.65052

Impact of Government and Other Institutions’ Support on Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Agribusiness Sector in Ghana

Evans Brako Ntiamoah*, Dongmei Li, Michael Kwamega

College of Management, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 18 March 2016; accepted 9 May 2016; published 12 May 2016

ABSTRACT

The focus of the study is to examine the impact of government and other Institutions’ support on the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises in agribusiness sector of Ghana. The research adopts quantitative research design. Research evidence was gathered via a questionnaire- based survey of selected agribusiness companies in Ghana. The variables used for study were tested through correlation and regression analysis. The results posit that government support had a statistically significant and direct effect on other institutions’ support and performance of SMEs. The results also indicate that government support had a positive and significant effect on performance of SMEs via the partial mediation effect of other institutions’ support. Conclusions of the study may help academics and managers in implementing the outcome in sequence to enhance other institutions’ support and upgrade performance of SME’s.

Keywords:

Government Support, Other Institutions’, Performance, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SME’s), Ghana

1. Introduction

The position of small and medium-sized enterprises in developing economies, especially Ghana as mechanisms of economic growth has not occur fully realized. SMEs established in minor urban and rural areas helps to reduce rural, urban migration by ensuring even supply of economic activities within a region. Through small and medium-scale enterprise, individuals can be able to utilize their little capital that would not be sufficient to finance a large business. They also accord to the local economy by bringing economic growth to the communities in which they are established. Large numbers of people depend on SMEs directly or indirectly [1] . Hiring a large number of people in the labour force, SMEs reduce the unemployment rate by employing large of the unskilled labour as assistants who may not be employed by the larger firms.

The future of small and medium-sized enterprise seems very promising according to trends in developed and developing countries [2] . This suggests that information uprising may increase the relative competitiveness of minor firms and also SMEs will play a huge role in technological advancement in the surroundings of the information revolution and the rising role in services.

In Ghana, SMEs occupy the largest market share of about 90% and provide about 85% of manufacturing employment [3] . The industrial practices of SMEs ranges from textile, leather making, agro-processing, detergent making, food processing, tailoring, Blacksmithing, mechanics, electronic assembling, bakery, furniture making, brick making, brewing of beverages, ceramics and timber felling to small scale mining [4] . Ghana is a country endowed with a huge of natural resources like gold, diamond, bauxite, timber etc. These resources serve as a source of benefit for SMEs in the shape of raw materials. However, the country is not able to utilize them fully to their advantage due to the constraints they face such as funds, machinery, and technical know-how.

In advanced economies, the contributions of SMEs are significant and are identified as the main engines for growth and enlargement [5] . SMEs also serve as important contributors of economic extension in developing countries. Again, SMEs confront a number of challenges such as obtaining credit facilities, strong government policies, lack of infrastructure and lack of skilled labour which hinder their growth, opportunities in addition to their role as mechanism of economic growth and development. These challenges make it inconvenient to create successful SMEs and realize their brim-full potential. As cited by [6] , while the set of SMEs development in Africa is high, their expectations for growth remains low liken to other economies in the world.

The significant role of SMEs can be realized if there are government supportive policies to help them gain access to capital, technology improvement, quality improvement, skill development and ingress to both domestic and international markets.

The rest of this research is structured as follows. Section 2 will propound the theoretical background to this study. Section 3 provides the conceptual framework and hypotheses. In Section 4, the research methodology of the research was discussed. Section 5 accords the statistical results and discussions of finding. Finally, this study in Section 6 grants the conclusion of the study.

2. Theoretical Background

Different researchers have usually given different meanings to this classification of business. SMEs have certainly not been refraining with the definition problem that is usually related with concepts which have many components. The definitions of firms by size differ among researchers. Some strive to use the capital assets while others use skill of work and income level. Others express SMEs in areas of their authorized position and method of production.

[7] tries to summarize the challenge of using size to explain the status of an organization by stating that in some sectors all firms may well be considered as small, whereas in other sectors there are perhaps no firms which remain small.

[8] are of the option that meaning of size of Enterprises suffers from a lack of comprehensive applicability. In their view, this is because enterprises may be form of in varying terms. Size has been defined in different surroundings, in terms of the number of workers, annual turnover, industry of enterprise, possession of enterprise, and value of fixed assets.

[9] review small and medium firms as privately held firms with 1 - 9 and 10 - 99 people employed, respectively. [10] explain SMEs as firms with fewer than 100 employees and fewer than ?5 million turnover. [11] examine small independent private limited firms with fewer than 200 employees and [12] appraise companies with sales under ?5 million as small.

It is clear from the numerous definitions that there is not a widespread consensus over what constitutes an SME. Definitions differ across industries and also covering countries. It is crucial now to examine meanings of SMEs given in the surroundings of Ghana.

2.1. The Meaning of SME from the Ghanaian Perspective

The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) adjudge firms with fewer than 10 employees as small-scale enterprises and their correlative with more than 10 workers as medium and large-sized enterprises. Ironically, the GSS in its national accounts examine companies with up to 9 employees as SMEs [4] . However, the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI) in Ghana applies both the “fixed asset and number of employees” criteria. It describes a small-scale enterprise as a company with not more than 9 workers, and has plant and machinery (excluding land, buildings and vehicles) not above 10 million Ghana cedis. The Ghana Enterprise Development Commission (GEDC), on the other side, uses a 10 million Ghanaian cedis upper limit sense for plant and machinery. It is important to be mindful that the process of valuing fixed assets poses a problem. Secondly, the continuous decline of the local currency as opposed to major trading currencies often makes such definitions outdated [4] .

In explaining small-scale enterprises in Ghana, [13] , and [14] prefer an employment cut-off point of 30 employees. [14] , however, categorize small-scale enterprises into three groups. These are: i) micro-employing less than 6 people; ii) very small-employing 6 - 9 people; iii) small-between 10 and 29 employees. A more current definition is the one stated by the Regional Project on Enterprise Development Ghana manufacturing poll paper. The survey outline classified firms into: i) micro enterprise, below 5 employees; ii) small enterprise, 5 - 29 employees; iii) medium enterprise, 30 - 99 workers; iv) large enterprise, 100 and more employees.

2.2. Relevance of SME Sector

The significance of SMEs to social and economic development in Ghana and like Africa is almost undisputed. Throughout the continent, SME promotion is a priority in the policy agenda of most African countries as it is widely recognized. There is no uncertainty that SMEs constitute the seed-bed for the forthcoming generation of African entrepreneurs. According to United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), SMEs report for more than 90% of all registered firms in Africa.

Small and medium rural and urban businesses have been one of the vital concerns to many policy makers in an endeavour to accelerate the rate of growth in an economy such as ours. These firms have been recognizing as the engine via which the growth objective of developing middle income countries like our nation can be achieved.

SMEs contribute employment and incomes to a large share of urban labour force and are a notable source of total output [15] . [16] reckon that SMEs employ about 22% of the adult population in many emerging countries. It is also approximated that SMEs generate about 50% of national output and provide about 60% employment to Ghanaians [17] .

Furthermore, SMEs lean to utilize mainly local raw substance that would otherwise be neglected and have less foreign exchange. They mobilize and utilize financial wealth that is otherwise dormant like family savings. SMEs by their activities promote local knowledge.

2.3. Constraints to SMEs Development

In the expression of the wide-ranging economic improvement introduced in Ghana since independence, SMEs still encounter a variety of limitations owing to the difficulty of exciting large fixed costs, the absence of economies of scale and scope in key factors of production, and the higher unit costs of supplying services to smaller firms. A World Bank research established that about 90% of small enterprises surveyed affirmed that credit was a major difficulty to new investment [13] [18] - [21] . Beneath are the set of difficulties recognized by the sector.

2.3.1. Input Constraint

According to [22] , SMEs encounter a range of difficulty in factor market. Conversely, resources availability and its cost were the most common limitations. Many of the SMEs in Ghana emphasized the high cost of attaining local raw materials; this may curtail from their poor cash streams [21] . [15] found that 5% of their sample cited the input constraints as a problem.

2.3.2. Managerial Inadequacies

Deficiency of managerial expertise puts substantial constraints on SMEs. Owners or managers of SMEs have inadequate managerial knowledge, attitude and skills in spite of the numerous institutions providing training and advisory services. They mostly improve their own approach to management through a method of trial and error. Most SMEs are owner managed and these owners often lack the required skills and knowledge to keep the company moving in today’s competitive environment. In the few cases where skills have been developed through other formal or informal ways, the right attitude to work, maintenance, law and civil life is often lacking.

Majority of persons who run SMEs are conventional lot whose educational background is lacking. Hereafter they may not be well prepared to carry out managerial schedules for their enterprises [23] .

2.3.3. Market Constraints

SMEs are normally confronted with greater external opposition and the need to enlarge market share. The nature of the impoverished population also adds to this. The few buyers tend to fall into those products produced by foreigners. This puts severe pressure on SMEs in rapports of efficiency, price, and quality and customer satisfaction. [24] testified that tailors in some part of Ghana who used to make several pairs of trousers in a month went deprived of any orders with the coming into outcome of trade liberalization.

2.3.4. Regulatory and Legal Constraints

High start-up price for firms, together with licensing and registration requirements has the likelihood to impose extreme and needless burden on SMEs. SMEs are adversely affected the most as an outcome of the high cost of settling legal claims together with the interruptions in court proceedings in registering. The challenging process and requirements to commence business has remained an issue for Small and Medium enterprises. The legalities in clearing goods from the ports and the processing of export documents are also an issue in rapports of the time it takes and the monetary values involved.

2.3.5. Inability to Capitalize on the Advancement in Technology

[25] describe technology as some of the most dramatic forces shaping people’s lives and businesses today. Most of SMEs who have adopted ICT have realized benefits and are very positive in continuing to invest and harvest those benefits [26] .

Technological improvement has rather modeled a great challenge to small businesses. This has resulted from their incapability to learn and utilize the immense benefit of the technological advancement.

Since the mid-1990s there has been a growing anxiety about the impact of technological modification on the work of micro and small enterprises. Even with change in technology, many small business entrepreneurs seem to be unfamiliar with new technologies.

Those who appear to be well positioned, they are most often unaware of this technology and if they know, it is not either locally available or not affordable or not situated to local conditions.

In Ghana, like many other African nations, the test of connecting local small enterprises with foreign investors and speeding up technological advancement still persists [27] . There is numerical divide between the rural and urban Ghana. With no influence supply in most of the rural areas, it is next to unbearable to have Internet connectivity and access to evidence and networks that are core in any enterprise. Thus technological modification, though intended to bring about economic change even among the rural lot, does not appear to answer to the plight of the rural entrepreneurs involved in SME operations. [28] identified absence of ICT knowledge and skills as one of the major challenges faced by SMEs.

2.3.6. Financing and Access to Credit Facility

Of all the constraints that SMEs face in Ghana, finance remains the major and dominant constraint of all. Credit constraints affecting to working capital and raw materials have been the single biggest drawback to the SMEs in Ghana. [29] recounted that 38% of the SMEs measured mention finance as a main constraint; SMEs have inadequate access to capital markets locally and internationally, in part because of the perception of complex risk, serious management weaknesses, lack of information, and the advanced costs of intermediation for smaller firms. As an outcome, SMEs often cannot achieve long-term finance in the form of debt from banks. In Sub-Sahara Africa, most small businesses fail in the first year due to lack of funding from government and traditional banks [30] .

In Ghana, the problems financing small firms have meaningfully hindered the role these SMEs play in the general macroeconomic performance of the Ghanaian economy. Financial constraints will form a main aspect of the discussions of this work.

2.4. SMEs Growth and Development

The goal of any firm is to make profit and growth. A firm is explained as an administrative organization whose legal entity may expand in time with the gathering of both physical resources, tangible or resources that are human nature [31] . The term growth in this context can be defined as an increase in size or other objects that can be quantified or a process of changes or improvements [31] . The firm size is the result of firm growth over a period of time and it should be renowned that firm growth is a process while firm size is a state [31] . The growth of a firm can be strong-minded by supply of capital, labour and suitable management and opportunities for investments that are profitable. The influential factor for a firm’s growth is the obtainability of resources to the firm [32] .

The government needs to recognize the contributions which small and medium enterprises make to the national economy and wealth establishment from the beginning and be considered as part and parcel of the economic development procedure [33] . According to [2] , independent of region and level of development between countries, most development lessons hold true for all SMEs.

In order to draw foreign investment for the growth of SMEs, peace and firmness is a key requirement. Researches show that war and crime deter many foreign investors from investing in private businesses. When it comes to peace and stability, Ghana is among the top nations in Africa and provides a conducive and a maintainable environment for the growth of businesses. Strong government policies, however, seem to be lacking in the business sector, especially small and medium businesses. Even though efforts have been made by the administrators of the nation to institute policies to promote and support SMEs in directive to achieve economic development and reduce poverty, there are still limited laws, administrative procedures and access assistance from government agencies [34] . As the development of SMEs is directly related with the boost in economic development and development, their priorities must be taken care of through institutions that help to function efficiently and effective regulations that helps to reduce administrative costs.

The need for government to draw and implement effective strategies in SME growth is clearly undeniable. According [35] , in order to improve SMEs growth and productivity, there must be a policy focus on the potential obstacles which hinder their growth and development. Strategies for expansion of SMEs must be integrated into the broader national development strategy or poverty lessening and growth strategy of transition and emerging countries. The expansion of SMEs requires a networking strategy where the governments are intelligent to implement sound macroeconomic policies, stakeholders are bright to develop conducive environments in addition SMEs are also able to device competitive operational performs and business strategies. These confirm proper execution of the stated strategies. Dialogue and partnership enhance effective communication, foster ownership of SME strategies and address the requests of SMEs more appropriately. It also brands SMEs to be credible politically and more sustainable.

The accomplishment of SMEs depends on investment in infrastructure, business services, support structures, and the capacity of policy makers and local level administrators to implement procedures. According to [36] , in order for SMEs to flourish, they need an enabling business environment, effective laws and regulations, needed infrastructure, access to finance from numerous financial institutions, training, knowledge about market opportunities and access to technology. Sustainable physical infrastructural development and corporate service delivery is necessary for access and integration of SMEs into local, regional, national and global markets.

Development and training of women in SMEs must be an important part of the SME expansion strategy at all stages. Women are known to account for an important share of private sector businesses and constitute about 75% of total entrepreneurs in SMEs in Ghana [37] . Their influence to poverty reduction and economic development is significant [38] [39] . Strategies to develop SMEs should therefore take into thought gender issues and address them accordingly with specific position to important areas.

2.5. Government Institutions Providing Support to SMEs

The government of Ghana in an effort to support the development of SMEs established various program and institutions aimed at promoting SME development. The Ghana Enterprise Development Commission (GEDC) officially known as Office of Business Promotion was the only coordinating body, providing technical and financial support to Ghanaian businesses in the initial 1970s. Its main role was helping to strengthen small-scale industries in general in Ghana. Later, the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI), the main government body attending to the affairs of small-scale enterprises was set-up within the Ministry of Industries, Science and Technology under Parliament Act 434 in 1981. Funded by the government of Ghana, the NBSSI was established to address the concern of small-scale businesses by organizing training programs for entrepreneurs, advising them on business operations and providing financial assistance in the form of loan schemes. It also cooperated with NGO’s and International establishments to receive support for small businesses. Ironically, this institution does not obtain the funding it needs to function well. Political interference of management affected its operations and there was poor remuneration of workers. These challenges limited the assistance they offer to small businesses [40] .

The Ghana Regional Appropriate Technology Industrial Service (GRATIS) was recognized by the Government of Ghana as a project under the Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology in 1987. It provided support to small scale businesses through the establishment of Intermediate Technology Transfer Units (ITTUS) in all the regions of Ghana. It aimed to provide employment opportunities, improve income levels and enhance the expansion of small scale industries at the grass root level through technology upgrading and transfer.

The Rural Enterprise Project (

The government had also set up organizations to provide financial support to SMEs. Under the Package of Action to Mitigate the Social Cost of Adjustment (PAMSCAD), an amount of US$2million was fixed aside to be given as credit to develop and train people for self-employment as part of the Entrepreneurship Program (ERP).

The Central Bank of Ghana also established a credit guarantee scheme to underwrite loans made by Commercial Banks to small scale enterprises. In 1998, Bank of Ghana obtained a US$28 million credit from the International Development Association (IDA) of the World Bank for the establishment of a Fund for Small and Medium Enterprises Development (FUSMED). FUSMED was to provide funding services through appropriate participating institutions such as commercial banks, merchant banks, development banks and additional financial institutions to SMEs in all sectors additional than primary agriculture, trading and real estate. The major weakness associated with this policy was that the lending risk fell full on the participating bank [4] [14] [40] [41] .

The problems facing SMEs suggest that the various institutions established by previous governments are either ineffective or they do not receive the necessary funds for their smooth running. These institutions must not be abandoned once established. There must be follow-up program to check their performance and also channel resources for their smooth running.

2.6. Other Government Support Institutions

Other governmental organizations have also offered support in the procedure of funds for small and medium-sized enterprises in Ghana to improve their growth and prosperity. Several of the donor interventions were received from USAID, World Bank and others. The USAID instituted the Trade and Investment program to SMEs in the non-traditional sector. TECHNOSERVE Ghana was another non-profit, nongovernmental organization that aided SMEs by training entrepreneurs to shape their businesses in demand to boost income and employment generation. It is funded by individuals, USAID and monies from contract projects by the government and the World Bank. However, they are challenged with the problem of limited finance [40] . UNDP also provided funds for the African Management Services Company which provides assistance to small and medium- sized businesses.

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis

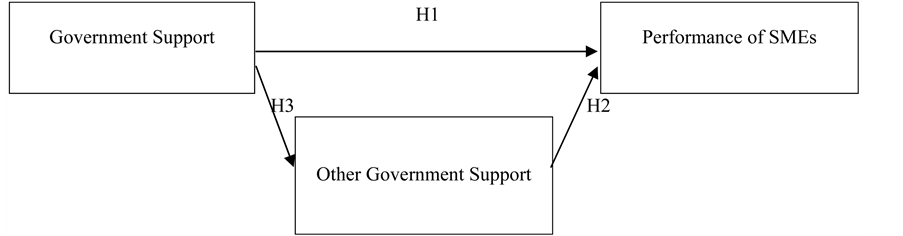

The proposed theoretical framework below describes the connecting relationships between three variables of the government support, other government support and performance of SMEs.

Source: Authors’ construct 2015

H1: Government support has a direct impact on performance of SMEs’;

H2: Other government support has a positive impact on performance of SMEs’;

H3: Other government support is a vital mediator in the government support and performance of SMEs’ relationship.

4. Research Methodology

The research consists of three steps, namely posing a question, collecting data to response the question, and presenting an answer to the question [42] . This research ponders on the relationship among variables more than on testing action effect, and uses correlation design. Established on the described research objective, this study adopted a correlation design. Correlation design permits us to predict an outcome and know the relation between variables.

The research was conducted in Koforidua the capital of the eastern part of Ghana. The location of the city makes it the commercial Centre and a nodal point from which roads radiate to the central business areas of the region. Small and medium-sized enterprises within Accra were chosen for the study.

The population of the survey consists of the management and non-management staff and customers of the selected enterprises in Ghana. The researchers used the simple random sampling. The study used a sample size of six hundred (600) and due to adequate time the researchers devoted for the data collection, the researchers got five hundred and forty-five (545) of the questionnaires that were administer.

5. Data Analysis

Government institutions and non-governmental institutions are predicators and performance of small and medium-sized enterprises is a criterion variable. Based on analysis of the collected data and using description statistics for demography, it was established that most respondents were male at 60.4% and the most of the research participants (49.7%) are aged between 25 and 40. Also, most people (48.2%) have some undergraduate education level besides most respondents are married (58.9%).

Moreover, to attain the research objective the connection among government Support, other government Support and performance of small and medium-sized enterprises were assessed, and from Table 1, the Pearson correlation was utilized. There is a strong relationship among government Support and performance of small and medium-sized enterprises with a correlation coefficient of 0.744 at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), other governmental Support and government Support with a correlation of 0.573 at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), performance of small and medium-sized enterprises and other governmental support with a correlation coefficient of 0.691 at the 0.01 level (2 tailed). This relation being positive signifies that an increase in government and other government support will results in higher productivity from the small and medium-sized enterprises (Table 2).

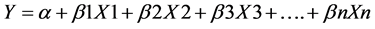

The regression model was established using the equation:

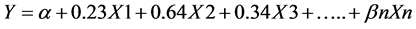

where: Y is the dependent variable, “α” is a regression constant; β1, β2, β3 and βn are the beta coefficients; and X1, X2, X3, and Xn are the independent (predicator) variables. Standardized beta coefficients were positioned in the regression equation. This discovered that development projects can be predicated as:

where: Y is (OPSMEs’); X1 is (GS); X2 is (OGS); X3 is (PSMEs’), and Xn is the nth predicator (Table 3).

Table 1. Shows the correlations between government support, other institutions support and performance and small and medium-sized enterprises.

Table 2. Shows the results of hypotheses testing.

Table 3. Shows the regression Analysis among three variables of the government support, other institutions’ support and performance of SMEs.

6. Conclusions

Although most of the respondents received support from the government, it was mostly in the form of loans. Access to loans has also proved to be very tough to small and medium firms due to high interest rates, collateral requirements and complicated processes [29] [43] . For those who gained access to government support, some used to enlarge their businesses whiles others acquired the necessary skills and knowledge to run their business. The government has made numerous attempts to support SMEs, but the study displays that the support is not significant. The development of the SME sector is an essential component in the growing of the Ghanaian economy. The government needs to set in place effective strategies to increase the growth and productivity of the sector. Establishing of an enabling environment would help in the proper structuring of SMEs in order to contribute profoundly to economic growth.

Other institutions’ do not have substantial impact on the operations of SMEs according to the fallouts of this study. Majority of the businesses do not obtain any support from NGOs. The support from NGOs were very many minimal and barely influenced the operation of small and medium enterprises.

Results of the study discovered that there is a high positive correlation among the constructs of government support, other institutions’ support and performance of SMEs.

Areas for Further Research

Further research is necessary to capture formulation and execution of effective policies by the government regarding expansion of the SME sector and also further studies can be conducted on the role government and other support institutions play in other areas of the economy.

Acknowledgements

“Every scripture is inspired by God and useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness”. 2 Timothy 3:16. Special thanks to everyone who in one way or the other made his paper a success. God bless you abundantly.

Cite this paper

Evans Brako Ntiamoah,Dongmei Li,Michael Kwamega, (2016) Impact of Government and Other Institutions’ Support on Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Agribusiness Sector in Ghana. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management,06,558-567. doi: 10.4236/ajibm.2016.65052

References

- 1. Fida, B.A. (2008) The Importance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Economic Development. The Free Library 2008.

http://www.thevillager.com.na/articles/1973/The-Importance-of-Small--Medium-Enterprises--SMEs--in-the-economy/ - 2. Capacity Development Center (2012) Empowering SMEs in Ghana for Global Competitiveness. Ghana Web Business News, Article 256015.

http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=246015 - 3. Mensah, S. (2004) A Review of SME Financing Schemes in Ghana. A Presentation at the UNIDO Regional Workshop of Financing SMEs, Accra, Ghana in March 2004.

http://www.doc88.com/p-5923947209413.html - 4. Kayanula, D. and Quartey, P. (2000) The Policy Environment for Promoting Small and Medium Sized Enterprise in Ghana and Malawi. Finance and Development Research Programme Working Paper. Series No.15.

- 5. Frimpong, C.Y. (2013) SMEs as an Engine of Social and Economic Growth in Africa (Modern Ghana Featured Article, 29 July 2013).

http://www.modernghana.com/news/478225/1/smes-as-an-engine-of-social-and-economic-developme.html - 6. Gatt, L. (2012) SMEs in Africa: Growth Despite Constraints. CIA Paper Series, 17 September 2012.

http://www.consultancyafrica.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1120:smes-in-africa-growth-despite-constraints&catid=82:african-industry-a-business&Itemid=266 - 7. Storey, D. (1994) Understanding the Small Business Sector. Routledge, London, 33-55.

- 8. Weston, J.F. and Copeland, T.E. (1998) Managerial Finance. CBS College Publishing, New York, 243-255.

- 9. Van der Wijst, D. (1989) Financial Structure in Small Business. Theory, Tests and Applications. Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems, 320, Springer-Verlag, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-45656-5 - 10. Jordan, J., Lowe J. and Taylor P. (1998) Strategy and Financial Policy in U.K. Small Firms. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 25, 1-27.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00176 - 11. Michael, N., Chittenden, F. and Poutziouris, P. (1999) Financial Policy and Capital Structure Choice in U.K. SMEs: Empirical Evidence from Company Panel Data. Small Business Economies, London, 12, 113-130

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1008010724051 - 12. López, G.J. and Aybar, A.C. (2000) An Empirical Method to the Financial Behaviour of Small and Medium Sized Companies. Small Business Economics, 14, 55-63.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1008139518709 - 13. Steel, W.F. and Webster, L.M. (1991) Small Enterprises in Ghana: Responses to Adjustment Industry. Series Paper, No. 33, The World Bank Industry and Energy Department, Washington DC.

- 14. Osei, B., Baah-Nuakoh, A., Tutu, K.A. and Sowa, N.K. (1993) Impact of Structural Adjustment on Small-Scale Enterprises in Ghana. In: Helmsing, A.H.J and Kolstee, T.H., Eds., Structural, Financial Policy and Assistance Programmes in Africa, IT Publications.

- 15. Aryeetey, E. (2001) Priority Research Topics Relating to Regulation and Competition in Ghana. Centre on Regulation and Competition Working Paper Sequence, University of Manchester, Manchester.

- 16. Daniels, L. and Ngwira, A. (1994) Results of a Nation-Wide Assessment on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Malawi. GEMINI Technical Report No. 53, PACT Publications, New York.

- 17. Business and Financial Times, 13/07/09.

- 18. Bolton, J.E. (1971) Report of the Committee of Analysis on Small Firms. HMSO, London, 3-7.

- 19. Liedholm, C. and Mead, D. (1987) Small Scale Industries in Emerging Countries: Empirical Evidence and Policy Consequences. International Development Paper No. 9, Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing.

- 20. Liedholm, C. (1990) Dynamic Issues of Small Scale Industry in Africa and the Roles of Policy. Gemini Technical Report 2, Washington DC.

- 21. Parker, R., Riopelle, R. and Steel, W. (1995) Small Enterprises Adjusting to Liberalization in Five African Countries. World Bank Discussion Paper No. 271, African Technical Department 47 Series, The World Bank, Washington DC.

- 22. Levy, B. (1993) Obstacles to Developing Indigenous Small and Medium Enterprises: An Empirical Assessment. The World Bank Economic Review, 7, 65-83.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/wber/7.1.65 - 23. King, K. and McGrath, S. (2002) Globalization, Enterprise and Knowledge: Education, Training and Development in Africa. Symposium, Oxford.

- 24. Parker, R., Riopelle, R. and Steel, W.F. (1998) Small Enterprises Adjusting to Liberalization in Five African Countries. World Bank Discussion Paper No. 271, African Technical Department Series, Washington DC.

- 25. Kotler, P. and Keller, K. (2006) Marketing Management. 12th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- 26. Ashrafi, R. and Murtaza, M. (2008) Use and Impact of ICT on SMEs in Oman. The Electronic Journal Information Systems Evaluation, 11, 125-138.

- 27. Bigsten, A.P., Collier, S., Dercon, M., Fafchamps, B., Gunning, G.W., et al. (2000) Credit Restrictions in Manufacturing Enterprises in Africa. Working Paper WPS/2000. Centre for the Research of African Economies, Oxford University, Oxford.

- 28. Duan, Y.Q., et al. (2002) Addressing ICT Skill Challenges in SMEs: Insights from Three Country Investigations. Journal of European Industrial Training, 26, 430-441.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090590210451524 - 29. Aryeetey, E., Baah-Nuakoh, A., Duggleby, T., Hettige, H. and Steel, W.F. (1994) Supply and Demand for Finance of Small Enterprises in Ghana. World Bank Discussion Paper No. 251, Technical Department, Africa Region, Washington DC.

http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/0-8213-2964-2

http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-2964-2 - 30. Abor, J. and Biekpe, N. (2006) Small Business Financing Initiatives in Ghana. Difficulties and Perspectives in Management, 4, 69-77.

- 31. Penrose, E. (1959) The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 32. Geroski, P. and Machin, S. (1992) Do Innovating firm Outperformed Non-Innovators? Business Strategy Review, 3, 79-90.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8616.1992.tb00030.x - 33. Freel, M.S. (2000) Do Small Innovating Firms Outperform Non-Innovators? Small Business Economics, 14, 195-210.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1008100206266 - 34. Harvie, C. and Lee, B.C. (2005) Introduction: The Role of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Achieving and Sustaining Growth and Performance. Faculty of Commerce-Papers (Archive), Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, 3-27.

http://works.bepress.com/charvie/52 - 35. Ayyagari, M., Beck, T. and Demirgüç-Kunt, A. (2003) Small and Medium Enterprises across the Globe: A New Database. World Bank Publications, Vol. 3127.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3127 - 36. Lukas, E. (2005) The Economic Role of SMEs in World Economy especially Europe. European Integration Studies, 4, 3-12.

- 37. KesseyKwaku, D. (2014) Micro Credit and Upgrade of Small and Medium Enterprises in Informal Sector of Ghana: Lessons from Experience. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 4, 768-780.

- 38. International Finance Corporation (IFC) (2014) Women-Owned SMEs: A Business Chance for Financial Institutions. A Market and Credit Gap Assessment and IFC’s Portfolio Gender Baseline, Washington DC.

http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/b229bb004322efde9814fc384c61d9f7/WomenOwnedSMes+Report-Final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES - 39. Kipnis, H. (2013) Financing Women-Owned SMEs in Private Education: A Case Study in Ghana. USAID.

http://wlsme.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/case_study_ghana_final_ecopy.pdf - 40. Adu-Amankwah, K. (1999) Trade Unions in the Informal Sector: Finding Their Bearings. Nine Country Papers, Labour Education 1999/3 No. 116, ILO.

http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---actrav/documents/publication/wcms_111494.pdf - 41. Frimpong, K.G. and Tetteh, K.E. (2009) Developing the Rural Economy of Ghana through Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs): Issues and Options. ATDF Journal, 5.

http://www.atdforum.org/IMG/pdf_Rural_Economy_EKT_and_Godfrey.pdf - 42. Creswell, J.W. (2009) Qualitative Analysis and Research Design: Choosing between Five Traditions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- 43. Buatsi, S.N. (2002) Financing Non-Traditional Exporters in Ghana. The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 17, 501-522.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08858620210442848

NOTES

*Corresponding author.