1. Introduction

Most research on fricative sounds excludes /h/ although /h/ is described as a voiceless glottal fricative in the International Phonetic Alphabet [1]. One reason for this exclusion is that /h/ does not show typical fricative spectrographic characteristics. As fricative sounds are produced with a narrow constriction in the oral cavity which results in a turbulent airflow, it follows that, as a glottal sound, /h/ would be produced with a turbulent airflow at the glottis or between the vocal folds. However, research has shown that the shape of the vocal tract for /h/ is the same as that for the neighboring sounds [2]. Therefore, a number of different descriptions for /h/ have been proposed.

Chomsky and Halle [3] describe /h/ as having similar distinctive features as /j/ with the features [-consonantal, -vocalic] suggesting that /h/ is a glide. Similarly, Fant [4] argues that /h/ has weak consonantal features but is not a vowel as it has less vowel-like qualities than neighboring vowels. Britton [5] concludes that /h/ is a voiceless glottal approximant in English as she argues that it is produced using the same organs as the following vowel.

Other researchers on the other hand, based on its articulation, describe /h/ as a voiceless or breathy voiced counterpart of the following vowel [6-11]. Lieberman

[12] explains that /h/ could symbolize a vowel excited by noise excitation generated at, or near, the level of the glottis. Ladefoged [11] reports that even when the vocal cords are apart, if there is substantial airflow, it would cause vocal cords to vibrate, which in turn would result in “breathy voice” or “murmur”. Similarly, Roach [7] argues that /h/ takes on the qualities of the preceding vowel thus phonetically it is a voiceless vowel but phonologically a consonant as vowels may precede and/or follow /h/. Roach further adds that when /h/ occurs between voiced sounds, it is produced with some frication described as “breathy voice”. Borden and Harris [13] state that when /h/ is at the beginning of a sentence it has the same spectrum as a voiceless vowel. In English, /h/ can also occur between vowels and in this position, the articulatory movement is continuous thus /h/ may not be realized as a completely voiceless sound.

Laufer [14], in his study investigating /h/ in Hebrew and Arabic, reports that glottal constriction is observable in both of these languages. He argues that when there is no constriction in the vocal tract, and the glottis is open as is the case in the production of /h/, airflow is obstructed in the glottis and frication occurs. Thus he concludes “glottal fricative” for /h/ is an appropriate description.

Keating [2] also describes /h/ as a glottal approximant. She adds that phonologists describe /h/ as the voiceless counterpart of the following vowel. If /h/ is the voiceless counterpart of the following vowel, then the formants of /h/ would be similar to those of the following vowel. Keating [2], based on spectrographic representations of /h/ from three different languages, states that “rather than acquiring feature values, /h/ is simply interpolated right through” (p. 282).

2. Spectrum of /h/

The spectra of fricatives are characteristically concentration of energy in high frequencies and the occurrence of the formant peaks are weak [15]. Formant peaks are typical spectral features of vowels as they represent the resonances of the vocal tract which are called formants and shape the spectrum [16].

One of the early studies of fricative spectra by Strevens [17] classified voiceless fricatives into three groups based on their place of articulation. He included /h/ in the ‘back group’ of fricatives but distinguished it from other back fricatives noting that /h/ has ‘formant-like structure’. Pickett [18] argues that for /h/, two different types of spectrum can be seen. First, the spectrum of /h/ is dependent on the neighboring vowels as the vowel following /h/ is formed before the production of frication. Second, with close front vowels, velar or upper pharyngeal location may be the source of the turbulence for /h/ rather than the lower pharynx or at the glottis which results in energy to be located in the region of F2 and F3 of the following vowel. Johnson [19] also shows that /h/ exhibits formants as do vowels due to the filtering action of the vocal tract.

3. Turkish /h/

In Turkish, /h/ occurs in all positions (word initially, medially and word finally) with all eight Turkish vowels /ʌ, ɛ, ɰ, i, ɔ, œ, u, y/. As in the literature, the status of /h/ in Turkish is not clear. Zimmer and Orgun [20] depict /h/ as a voiceless glottal fricative but argue that /h/ in final position may be realized as a voiceless velar fricative. Other researchers also describe /h/ as voiceless glottal fricative but this is based mainly on impressionistic description rather than on acoustic studies [21,22].

Lewis [23] and Sezer [24] report that /h/ in Turkish is optionally deleted in fast speech but not in all contexts. The contexts in which /h/ is optionally deleted is listed as follows; before sonorants, but not after them; after voiceless stops and affricates, but not before them; before and after voiceless fricatives, inter-vocalically, word-finally, but not word initially. When deleted in pre-consonantal or final position, compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel occurs.

Mielke [25] argues that, there is energy in the F2 area but less energy in the F1 and F0 areas as expected in a sonorant consonant, which is distinctive of Turkish /h/. Selen [26] defines Turkish /h/ as a glottal consonant accompanied by “breathy voice” and as taking on the features of the following vowel. But acoustic studies of Turkish /h/ are very limited. Therefore, this study explores the spectrographic characteristics of /h/ in Turkish.

4. Method

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Eskişehir Osmangazi University. This study is based on voice recordings of participants reading a number of word lists. Although the study did not involve any invasive techniques and the recordings are not publicly available, each participant was asked to sign a consent form prior to the recordings.

4.1. Participants

Speech samples of six native Turkish speakers (three females and three males), aged 19 - 23 recruited from the Anadolu University student population were recorded. All were native speakers of Turkish. None of the participants reported any known history of either speech or hearing impairment. Participants were paid for their participation.

4.2. Materials

Test words consisted of 48 monosyllabic and disyllabic words containing /h/ in which /h/ was followed by one of the Turkish vowels /ʌ, ɛ, ɰ, i, ɔ, œ, u, y/ in word initial, word final, syllable-initial and syllable final positions. In the selection and formation of the test words, attention was paid to make the phonetic context in which /h/ occurred similar. In disyllabic words, /h/ was followed (in syllable final position) or preceded (in syllable initial position) by a liquid (see Table 1). Thus, 38% of the test words were real words and 62% were nonwords. The test words occurred in the carrier phrase “Oya____oku” (Oya read ____). The 48 words were randomized seven times resulting in seven lists. The first and last lists were excluded from the analysis. A total of 1440 tokens (8 vowels x 6 positions x 5 repetitions x 6 subjects) were analyzed.

4.3. Procedure and Analysis

Speakers were recorded in the Anadolu University, Speech and Language Therapy Center, Phoniatry Unit, in a quiet room with a high-quality microphone (Shure SM48). The microphone was placed at approximately a 45-degree angle and 15 - 20 cm away from the speaker’s mouth.

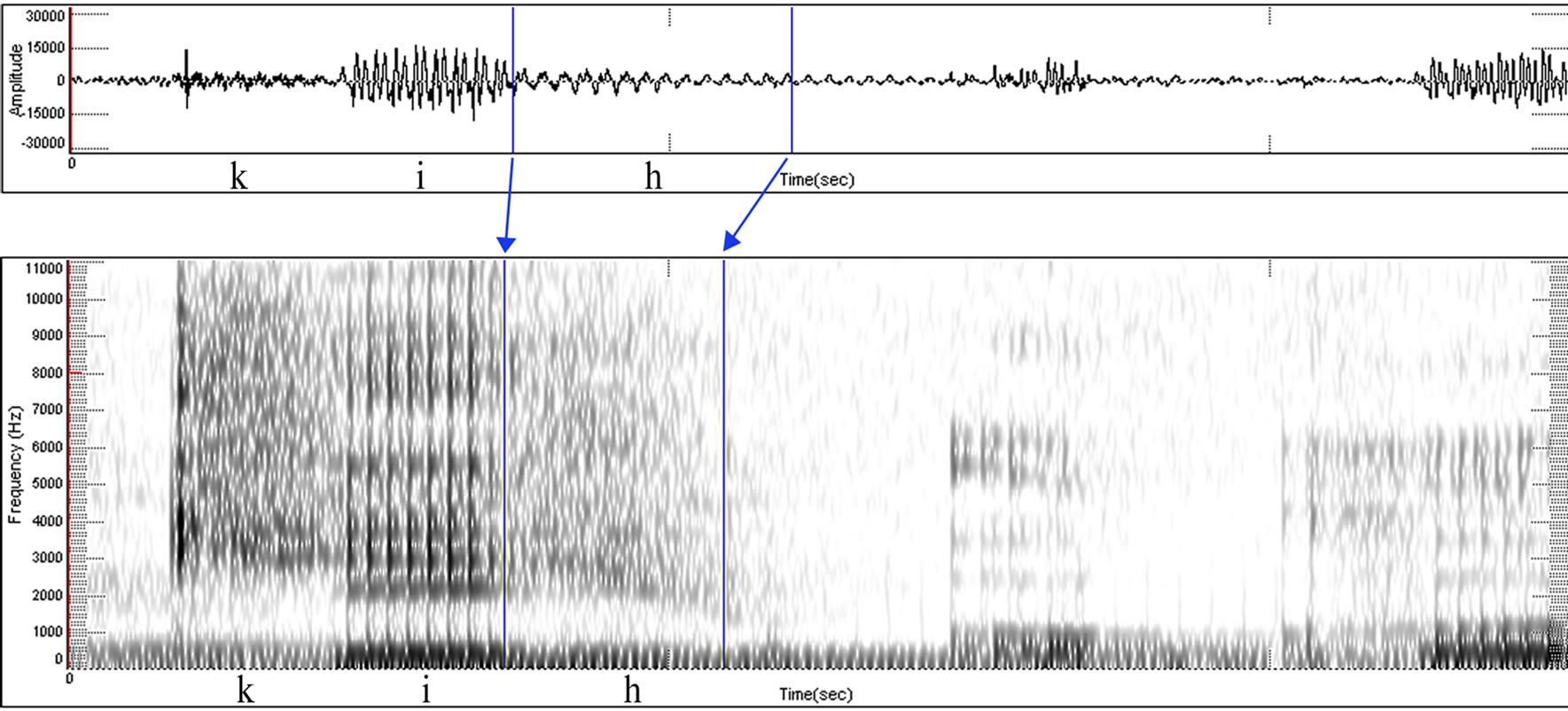

All recordings were sampled at 22.5 KHz sampling rate (11-kHz low-pass filter) on Computerized Speech Lab (CSL) Model 4500. /h/ segmentation involved the simultaneous consultation of waveform and wideband spectrogram. /h/ was defined as the interval from the offset of the preceding vowel indicated by substantial decrease in the waveform amplitude to substantial increase in the waveform amplitude corresponding to the onset of the following vowel.

After segmentation, each token was classified based on its spectrographic characteristics from 1 through 3, with the following definitions.

1) Segment exhibiting formants (as illustrated in Figure 1)

2) Segment exhibiting frication (but no formants) with energy in lower frequencies (as illustrated in Figure 2)

3) Segment exhibiting almost no energy (as illustrated in Figure 3)

Chi-square test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference among the three categories described above.

5. Results

5.1. Overall Data

As seen in Table 2, in Turkish, 72% of all the words with /h/ exhibit formant patterns which are characteristics of vowels. In only 6% of the words, /h/ appears with fricative qualities. In 22% of the words, no energy is seen (i.e., white space in the spectrogram). As seen in Table 3, statistical analysis indicates that there is a significant difference among the three categories (χ2 (2, N = 1440) = 1121.413; p < 0.05).

Also, Marascuillo Method used for to determine among which categories have the differences. According to this, formant patterns-frication, formant patterns-no energy and no energy-frication percentage have the significance differences (p < 0.05).

5.2. Vowel Context

To determine whether vowel context has an effect on the spectrographic characteristics of /h/, the data is analyzed for each vowel context separately. The results of the Chisquare showed that the three spectrographic characteristics differ significantly for all vowels (χ2 (2, N = 1440) = 255,686, p < 0.05).

As seen in Table 4, formant pattern was found more frequently for /h/ in all vowel contexts except for /u/. In both /ʌ/ and /ɛ/ contexts, 96% of /h/ appears with formants.

This is followed by /h/ in /œ/ context with 86%, which in turn is followed by /ɔ/ with 83%. Similarly, /h/ in the context of the vowels /y/ (77%), /i/ (66%), /o/ (54%) also exhibit formant patterns more frequently than they do other spectrographic characteristics. Only in /u/ context, /h/ surfaces with no energy more frequently (72%) and formant pattern is seen in 22% of the words.

Among all the vowel contexts, frication is more frequent in the context of /i/. In the production of /i/, a high vowel, the tongue body is raised to the palate leaving a small passage for airflow. Thus, in the case of /i/, it is usual for the passage to become so narrow that it is produced as a fricative (17).

5.3. Number of Syllables

To determine whether number of syllables have an effect on spectrographic characteristics of /h/, monosyllabic and disyllabic words were analyzed separately. The results of Chi-square showed that the number of syllables did not have an effect on the spectrographic characteristics of /h/ in Turkish (χ2(2, N = 1440) = 1506, p > 0.05). /h/ shows similar spectrographic properties regardless of number of syllables.

As seen in Table 5, in both mono and disyllabic words, /h/ shows formants more frequently (71% and 73%, respectively) than no energy (23% and 21%, respectively) and frication (6% and 6%).

5.4. Position within Syllable

To determine whether the position of /h/ within a syllable

Figure 2. Segment exhibiting friction (but no formants) with energy in lower frequencies.

Figure 3. Segment exhibiting almost no energy.

has an effect on the spectrographic properties of /h/, different positions are analyzed separately. The results of Chi-square showed that the three spectrographic characteristics differ significantly for between syllable initial and syllable final position among the three spectrographic characteristics (χ2 (2, N = 1440) = 10,373, p < 0.05).

Table 6 shows the number of occurrences of formants, frication and no energy for /h/ in different positions within a word and syllable. /h/ exhibits formants more frequently than frication and no energy in all different positions.