Development of the Urban Real Estate Market in Ribeirão Preto during the Old Republic (Brazil, 1889-1930) ()

1. Introduction

Throughout the second half of the 19th Century and the first decades of the 20th Century, the growth and consolidation of the coffee crop economy was the major factor behind the development of the country, the state of São Paulo and most especially the producer regions like Ribeirão Preto.

In 1874, the city of Ribeirão Preto was founded; when the first councilmen and Justices of the Peace were elected, the estimated population was around 5500 people, including Brazilians, slaves and foreigners [1] . The municipal budget for fiscal year 1874/75 [2] was $1054,000 thousand réis [3] , which corresponded to 0.0010% of the Central Government’s budget for the same period. This minute budget was compatible for a city that in 1874 had 4 streets, 6 crossings and 2 squares [4] . For illustration purposes alone concerning subsequent development, we can say that 37 years later, in 1911, the budget for the city of Ribeirão Preto already represented 0.09% of the federal budget and 0.48% of the total budget for municipalities [5] .

The population of Ribeirão Preto, according to census data, reached 12,035 inhabitants in 1890, jumping to 59,105 in 1900, and 68,838 in 1920 [6] . These data do not consider the populations of the municipalities of Sertãozinho and Cravinhos, which became independent from Ribeirão Preto in 1896 and 1897, respectively. The incorporation of the inhabitants of these two cities in 1900 and 1920 would expand the population to 100,095 and 125,911, respectively, pointing to an average growth between 1890 and 1920 of 8.14% per year.

This development led to the emergence of a dynamic urban economy, with the growth of several fundamental economic activities for the proper functioning of the coffee crop economy and for meeting the basic needs (personal and domestic) of the urban and rural inhabitants.

City growth thus results from development in the rural area, but also, gradually, gaining autonomy by constituting nuclei of activity geared not only toward serving the surrounding rural area but also, in the case of Ribeirão Preto, other urban and rural areas of neighboring municipalities.

The real estate market is associated to this development and serves as an indicator for it. Our objective in this paper is to understand the dynamic of Ribeirão Preto’s development during the Old Republic through the real estate transactions of houses, buildings and urban lots. Based on this, the paper is structured in three sections, besides this introduction. In the following section, we make some observations concerning the sources used, as well as the presentation of some general data about Ribeirão Preto’s real estate market. In Section 2, we examine the markets for several types of properties: residential, commercial, services, industries and lots, seeking to underscore their main characteristics and the sums involved. Finally, in Final Remarks, we summarize the results obtained and make some generalizations.

2. Some General Data

First, we will would to point out a limitation of this source for a more detailed study of urban dynamics, since in our opinion it would be subject to other variables not tied only to economic logic, or better, in which the economic logic would not be such a decisive factor. For example, we refer to the municipal behavior and the political dynamic urban policy certainly affected the rural world, but it affected the urban real estate market much faster and with much greater weight.

Despite these restrictions, in the properties’ purchase and sale deeds, the urban-related variables allowed us to identify some interesting points regarding growth and development of the nucleus tied to a strong coffee crop economy. Details regarding the traders and the property itself appeared in most of the transactions, such as: street, district, negotiation price, and size, among other variables. The faultiest point in most of the deeds that detailed urban property negotiations refer to the size of urban properties with constructed area, which made it impossible for us to use a standard measure to verify valorization over time of these same properties.

Urban growth occurred in a constant and accelerated manner. In our study, for the entire Old Republic period, of the 6001 deeds studied, 4772 referred to urban properties, or 79%. This urban growth occurred starting with a practically nonexistent nucleus in which, in 1874, there were no urban property negotiations, demonstrating a lack of dynamism in the city of Ribeirão Preto. This all changed rapidly with the “discovery” of the site as a potential large scale coffee producer, mainly by Luiz Pereira Barreto and Martinho Prado Júnior, that same decade. The arrival of the railroad in 1883 further enhanced this growth. What we then observe is expressive development in which the business with lots and homes or commercial establishments gains an expressive dimension in the local scenario.

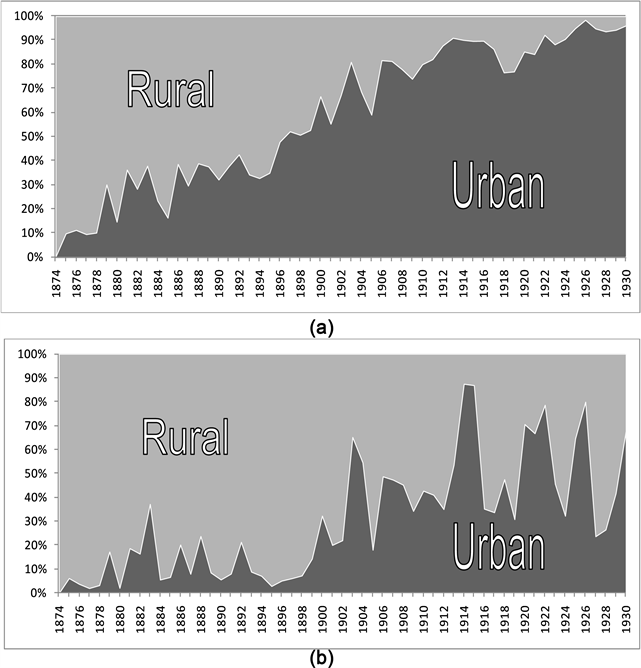

In Graph 1, we can visualize this strong growth in urban business compared to rural business. In the beginning of the Republic, the proportion of rural business was 62% compared to just 38% of urban business. However, the importance

Graph 1. Relative participation of urban and rural business in Ribeirão Preto (1874-1930). (a) Number of transactions; (b) Transaction values. Sources: Primary data: property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

of rural transaction, in terms of negotiated sums, remained important, despite the slight drop from 1900 forward.

In 1897, for the first time in the location’s history, more urban than rural properties were negotiated at a proportion of 52% to 48%, respectively. From that moment on, the urban market would have greater demand than the rural, reaching 96% of all real estate deals concluded by the end of the Old Republic period. Besides this relative reduction in rural business, there was also a reduction in absolute numbers, showing a decrease in interest in rural lands, very possibly due to the oscillations in the coffee crop market, which was the main indicator for profitability in Ribeirão Preto’s farms.

Total urban transaction values went from zero in 1874 to 222 contos de réis in 1929, reaching, as we can see in Table 1, peaks with volumes greater than 500 contos de réis in just one year. The city’s initial development was conditioned to

![]()

Table 1. Total value of urban transactions year by year in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

aValues already discounted from inflation for the period, in contos de réis. Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

coffee’s development. In the beginning of the 1890s we can see that investments in the urban real estate market had a strong correlation with investments in the rural real estate market, thus indicating greater dependence of the city on the field. There were strong peaks in investments in 1890 and 1891 in dwellings and lots, during the same period the rural area suffered the influence of favorable winds from the Encilhamento [7] .

The expressive dependence of urban development on the performance of the coffee crop culture becomes even more evident in the second boom cycle of urban investments. Also in Table 1, we see that from 1892 to 1905, the number of deals was always under 100, and the total values for annual transactions did not exceed 70 contos de réis, a volume much less than 1890-91. The number of transactions and the negotiated volume would only be recovered after 1906, when there were 108 transactions with a total business volume of 154 contos de réis, in real terms. From 1906 to 1913, we see an expressive boom in the urban real estate market, which peaked in 1912, with a total of 566 contos de réis. This period is marked by very favorable conditions for the Ribeirão Preto coffee crop market, in view of the success in coffee valorization policy implemented with the Taubaté Covenant of 1906 [8] .

3. Property Types

Five types of property were identified, grouped by the most common name for identifying them, since in some cases the same type of property was identified by two or more manners in urban purchase and sale deeds.

Initially, the most common properties were dwellings, which in some cases were also called “dwelling buildings” or “residential homes”. Besides the dwellings, there was also a variant which were dwellings in which the front was used for commerce, and the residents lived in the back of the house, carrying out commercial activities in the front. They were called “dwelling and commercial homes” or “dwellings with fronts structured for commerce”, etc.

There were also those properties fully geared toward commerce, identified as “commercial buildings”. The fourth category of property was urban country houses, identified as such or in some cases catalogued as such in our study by their characteristic of being small properties existing on already identified streets in the municipality or because they were “in front” of a certain street, that is, they were properties near the urban area or were near the urban ambit with its development and where identification could be made according to the street nearest the property.

Lots comprise the final category we identified. An interesting characteristic of the lots is that they served as a parameter for us to identify growing interest in urbanization, since the opening of new streets created new lots, although always to the detriment of productive farmland surrounding the urban center. In other words, there was a trade-off in the economic sense between urban growth and rural lands. In this case, the cost of opportunity was the lost possibility of coffee production with each new street opened and each new city block created. Nevertheless, the relative importance of the lots in these negotiations increased substantially over the period studied.

In Table 2, we see this growing importance of urban over rural. Throughout the period of the Old Republic, dwellings represented 42% of total properties. Dwellings that also had their fronts use for commercial purposes formed a reduced number of properties. Urban country houses totaled 138 properties or 3% and commercial buildings 130 properties or 2.5% of the total. The most prominent were the urban lots with the highest percentage: 52.0%.

3.1. Non-Residential Properties and Performance Sectors

Urban development of Ribeirão Preto should also necessarily be understood as the development of a regional commercial center. The strength of commerce is still seen today to the detriment of industry with an insignificant participation in the directions of this location’s economy, except for agroindustry, as a consequence of the very dynamics of agribusiness from coffee to sugarcane, and including cotton and corn, for example.

The municipality of Ribeirão Preto grew with commerce as its core dynamic and it became a regional center for shopping, possibly as a result of the transportation infrastructure available and because nearly all the main participants in the region’s agribusiness had separated from what was once Ribeirão Preto at the end of the 19th Century. Thus, finally, the prospering of this location as a commercial point of reference for residents of neighboring municipalities may have been the result of the strength of the coffee crop economy which had Ribeirão Preto as a point of reference, including for immigrants, where a significant portion of those who headed to Northeast São Paulo moved to the city.

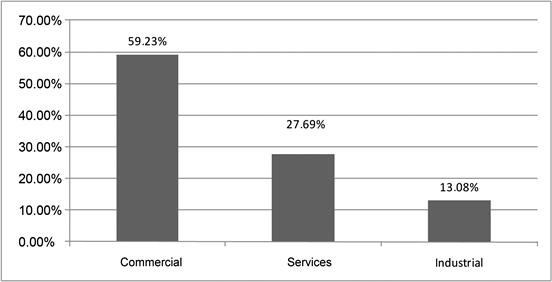

The participation of commercial properties in total real estate transactions during the Old Republic demonstrates this preference. While all industrial properties only totaled 13.08% of business and service provider properties totaled 27.69% of business, commercial properties totaled nearly 59.23% (Graph 2). Together, commerce and services represented practically 9 out of every 10 properties traded. A first exception we could make to put these numbers into better perspective would be to imagine that an industrial property, given the

![]()

Table 2. Types of urban properties in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

nature of the industrial activity, would represent much more in terms of allocated capital and, thus, would have greater economic importance, taking into account the immobilization of equipment with greater added value than the establishments used for commerce and services.

From Table 3, we can see that this did not occur in Ribeirão Preto. While the industrial properties represented a total of only 9.6%, commercial properties had a 71.53% share in traded financial volume and the properties geared toward services represented 18.9%. Adding commerce and services, we have a significant real estate value of 90.45% (Table 3).

Business oriented properties were also concentrated in terms of location. The area near the municipal market and the railroad station became the preferred site for commerce. Business’ concentration in this was thus strategic, enabling easy and convenient access for residents from other locations coming to do business and using.

Álvares Cabral, Amador Bueno, Duque de Caxias, Saldanha Marinho and General Osório streets―all located near the municipal market and the railroad station―concentrate seven out of ten non-residential establishments in Ribeirão Preto negotiated in the period (Table 4). This indicator of strong geographic concentration enables us to visualize how shopping in Ribeirão Preto would be

Graph 2. Commercial properties: participation of industry, commerce and services in total property owners in Ribeirão Preto (1874-1930). Sources: Primary data: property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

![]()

Table 3. Relative participation of commercial, industrial and service properties in real estate transaction in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

![]()

Table 4. Commercial concentration: the most used streets for commerce industry and services in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

![]()

Figure 1. Rua General Osório and Ribeirão Preto’s commercial downtown (1927). Source: Public and Historical Archive of Ribeirão Preto.

facilitated for consumers in the location or in neighboring cities (Figure 1). These streets represent a depreciated area of the city in current days called the “lower city”, certainly as a result of this commercial nature, which did not make them attractive for establishing residential dwellings.

3.2. Commercial Properties

The greatest level of negotiation occurred among commercial properties considering all types of nonresidential properties, given the proportion between the study of existing properties and number of businesses. Throughout the entire Old Republic period, with variations over the years, Ribeirão Preto had an average of 400 commercial establishments, with some years totaling fewer than 200 and others closer to 1000 [9] .

Given this average, a total of 77 negotiations seems relatively high to us, indicating a certain difficulty in maintaining the commercial undertaking over time on the part of the owners. There were times when nearly 10% of all existing commercial establishments were negotiated. This occurred, for example, in 1914, possibly as a result of economic difficulties in face of the beginning of World War I.

Among the commercial properties, commercial houses, also called “commercial houses for sundries” or simply “sundries” were the most prominent. This sort of establishment was the most common in municipal retail commerce given the flexibility of the stock composition. These commercial houses were successful at the time when specialization in retail commerce was not considered a competitive advantage for the company:

Probably, the more diverse product needs the company negotiated, the better it was considered among clients, perhaps even by virtue of the difficulty in locomotion for most the population at the time. There was a great variety of items that appeared in stock at these establishments, such as: several types of foods, beverages, furniture, tools, shoes, hats, dinnerware, perfumery, cigars, etc.

We can see this on the deeds, because there were very few cases of commercial houses with descriptions of little variety in products available, and we can also imagine the seller did not make the sale with all his stock or that there was no large variety of stock available on the date of the sale. Despite this possibility in a few cases, in most negotiations “all furniture, utensils and existing merchandise” was sold.

The average value of sundries establishment transactions, around 7.6 contos de réis, was the highest among all types of negotiated commercial establishments [10] .

The first bakery negotiated in the city was in 1898. The bakery owned by João de Souza Cardoso was sold to the baker Antonio Martiniano de Moura Albuquerque for four contos de réis [11] . This type of establishment, exactly as we know it today, was not the most common establishment for selling bread, thus the reduced share. The commercial houses themselves had the equipment to make dough and bread, thus supplying this market. This is even seen in the added value of these establishments, which in general were not valorized in the local market. Even those with a more complete structure, such as Joaquim Torres’ bakery, had them in moderate proportions, because it was sold for only 2.1 contos de réis. The bakery located on Rua São Sebastião had: “01 structure for business, 01 counter, 02 large windows, 08 marble tables, 06 wooden tables, 25 straw chairs, 01 large mirror, 03 pictures, 01 statue with marble stone, 01 oven covered with zinc tiles for a bakery constructed of bricks and stones, 06 boards, 01 large table for rolling out dough, installation with 05 lamps for the oven, 01 corkscrew and diverse business merchandise.”

Pharmacies were also negotiated frequently, most as companies negotiated together with their medications. This made the individual value of the business relatively high. Other types of establishment, in a smaller proportion, also appeared, such as: bars, furniture stores, sweet shops, hat stores, glass stores and shoe stores. The low variety of specific commercial establishments, as already underscored in this topic, is probably due to the existence of commercial houses that provided a large part of the commerce needs, leaving little room for specialized establishments.

3.3. Service Properties

Parts of the activities tied only to services could not be captured by the property purchase and sale deeds, since in many cases exercising the professional activity did not necessarily require a fixed establishment or even sophisticated equipment. Furthermore, many professionals exercised these activities at home or would go to their clients’ homes.

Marcondes & Garavazo [12] , studying commerce and industry in Ribeirão Preto ascertained that the service sector share reached nearly 1/3, with the freelancers and service providers having expressive representation in city activities.

These numbers are still very similar to those we raised through properties, like those obtained for the industrial and commercial sectors, for the relative share of real estate negotiations destined for each activity. However, the classification of what would be considered a service or commerce differed a little in our work in relation to the aforementioned authors. For example, the profession of pharmacist, classified as a service, had typical characteristics of medication sales in structuring the professional activity and in resource allocation. Thus, we did not include the pharmacy in the service sector, although the pharmaceutical professional presents characteristics that often induce us to classify him as a service provider. In property purchase and sale deeds we basically capture the pharmacy owner as a merchant.

In part, this occurred because of the very nature of the existing stocks at the negotiation. Besides the stock of medications, other products were frequently listed in the deeds and they characterized the pharmacy not as a simple service provider related to health, but also as commerce of medications, personal care and beauty products, such as toiletry. Therefore, in order to characterize them as services, we opt for those activities only geared toward service providing, and we classified as commerce all those activities that included the provision of services, but which also had a strong commercial connotation.

Based on these criteria, we identified those properties listed in Table 5 & Table 6 as services. These properties include a number of hotels and boarding houses, restaurants, mechanic garages, barber shops and some properties that had only one negotiation throughout the entire period: cinema, lottery agency and a phone company, gold and silver plating shop and pool hall.

The strong dynamic of property sales related to lodging shows us Ribeirão Preto’s convergence towards a regional business center. There were 16 negotiations of hotels and boarding houses, mainly located on Duque de Caxias, General Osório, Saldanha Marinho and Amador Bueno streets, that is, near the city’s train station.

Most of the hotels and boarding houses that appear on property purchase and sale deeds were small properties, generally residences their owners transformed

![]()

Table 5. Commercial establishments negotiated in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

![]()

Table 6. Service establishments negotiated in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

into inns. These hotel owners sought profits from temporary workers and especially businessmen passing through town probably as a consequence of local commerce or agribusiness. Most of the businesses presented relatively low negotiation values if we consider that this type of activity required a considerable investment in expensive fixed assets during the 19th and beginning of the 20th Centuries, for example, assets like: beds, wardrobes, stands, etc. In general they barely went for more than 3 contos de réis.

The participation of larger properties in this line was probably small. In few cases, there were negotiations of larger hotels, such as the negotiation of a hotel called Demantino for 19 contos de réis, with all its belongings [13] . Another negotiation that called our attention due to the size of the hotel was the property of José Martins Arantes sold for 16 contos de réis in 1893, containing “33 beds, 22 room tables, 24 chairs, 4 marble stone tables, 1 American clock, 3 dinner tables and 2 stoves.” That was the only negotiation in the period studied of the buyer José Venâncio de Carvalho.

Therefore, these establishments only represent a parcel of the service sector that needed investments in fixed assets to function. Activities such as shoemakers, blacksmiths, bricklayers and others that did not necessarily need their own site for operations, obviously were not detected in property purchase and sale deeds.

3.4. Industrial Properties

What occurred with service properties did not occur with industrial properties. The functioning of an industry would necessarily require major investments in capital goods, many of which highly specific to that industrial activity, and having, as a result, to be sold together most of the times.

The industries may have little representation in properties of this type sold during the Old Republic, with only 13.08% of the total titles surveyed. These industries had the common characteristic of being industries with a low degree of sophistication in relation to the production process, except perhaps the breweries, which had a more complex process. Another characteristic was the tendency for industries to exist related to the food sector and end users, with no negotiation of industries geared toward the production of capital goods or durable goods, indicating little representation of this type of industry (Table 7).

Even the breweries were small companies with processes evidenced as artisanal from the description of the equipment in these factories (Table 7). Furthermore, the maximum value for which one of these small breweries was sold was tree contos de réis. Although few large industries stood out in this period, they were an exception to the rule for small industries with simple and low capital investment production processes, many geared toward the food sector and a few

![]()

Table 7. Industrial establishments negotiated in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

related to the furniture industry.

We must underscore that the lack of prominence of the industrial sector in Ribeirão Preto, although the large accumulation of capital from coffee enabled alternative investments [14] , is mainly due to the results obtained from agribusiness during the entire Old Republic. The return on investments tied to land at the time, even during the most tumultuous years for the coffee sector, was exceptionally high. Even compared to alternative profitability in investments in other sectors, such as the financial market itself and money loaned at interest, land and coffee were safe ways to guarantee a good rate of return and thus reduced incentive for large coffee growers to seek significant diversification of investments.

Although there are some exceptions in this sense, such as Martinho Prado Júnior, who invested in the industrial sector, the most common were investments in land and bigger plantations and, occasionally, only a diversification between planted crops. Taking into account the average valorization of land with coffee during the Old Republic, we take this analysis little farther and conclude that such behavior was certainly the most rational possible on the part of coffee growers, and therefore not a behavior tied to an archaic mentality to the detriment of an urban-industrial mentality. The economic logic associated with the coffee protection policy drove coffee growers to invest profits in the agrarian sector and, if they had acted differently-from an economic logic perspective in terms of the cost of opportunity-they would be committing a business error of large proportions.

3.5. Lots

Lots had an expressive importance in urban deeds. Of the 4608 urban property purchase and sale deeds, lots participated with a total of 2392 trades, that is, 51.94%. Since some of the deeds described the size in palms, but most lot deals described the measurements in meters, we opted to maintain this original measure, since the metric measurement occurred in very restricted number of cases.

Analyzing Graph 3, we can perceive a cyclical standard between the ratio of sales of constructed properties and lots. In this graph, we try to identify the share of each type of urban property, only considering constructed properties and lots. We can see that there were three growth cycles from the proportion of lots, immediately followed by growth periods in constructed areas. The first year of the Republic still indicated low interest in the real estate market for lots, with only 3.7% of a total of 54 properties were lots negotiated without any type of improvement.

Nevertheless, interest in the lots grew constantly in subsequent years indicating a growing demand for urban housing properties. This gradual growth in lots in relation to constructed properties revealed a new dynamic of urban expansion as a result of the population growth and positive externalities of the coffee crop economy in local population income.

Graph 3. Relative share of lots and constructed areas in Ribeirão Preto (1874-1930). Sources: Primary data: property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

Considering a market that was practically nonexistent just a few years before the end of the imperial period, the real estate market for urban lots had a direct impact on this new dynamic for development. Between 1874 and 1884, there was no negotiation at all involving lots [15] . Therefore, lot making process and the separate sale of lots for constructing dwellings began when the few existing streets became insufficient to cover the increase in demand, mainly caused by the arrival of European immigrants, mainly Italians.

These cycles clearly show the ratio of lot limits and constructed areas. The initial incentive in opening new streets and expanding the existing streets on the part of country house owners and areas thus far used for crops was considered demographic growth. Lots were created that would be sold later, so that lot expansion periods related to negotiations of already constructed properties would create alternating cycles in the ratios of negotiated lots and homes.

We also tried to identify, approximately, the new streets opened in the area. For such, we used the criteria of accounting for every street name and the first time they appeared since 1870. The main objective was to try and compare lot ratio data and their location and also to determine whether they were lots on open streets or in new developments.

From 1889 to 1930, 223 new streets appeared in the property purchase and sale deeds (Table 8). We have this number as an estimate, since we could consider the existence of some streets that were not traded throughout the previous period, from 1874 to 1889. In this case, we would account for a preexisting street as a new street. However, in this criterion, we did not identify any street from the old downtown region of the city, appearing in the Republican period and with a reasonable degree of certainty we can affirm it to be highly unlikely for there not to be any trade on a specific street throughout nearly the entire decade from 1870 to 1880.

Of the 223 streets, most appeared between 1921 and 1930, with 39.00% of the total. However, the previous period also represented a period of growth in new streets, showing that the urban growth dynamic in Ribeirão Preto went through distinct phases, with the initial period of 1889-1900 and the first decade of the 20th Century of little significance for the expansion of lots in new streets. However, there was significant population growth that did not affect the emergence of new streets with lots in any proportional manner. At least, not immediately (Table 8).

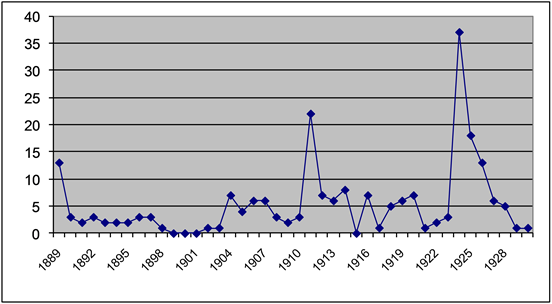

From Graph 4, analyzing the new streets opened over time, we can detect the similarity with the lot proportion graph, at least in terms of the period after 1910, where there is a clear proportion between cycles of new streets followed by cycles of more lots being negotiated. However, for the two initial decades, this ratio did not occur, despite the strong pace of lot sales. Since more lots were being negotiated, but without the emergence of new streets, we concluded that they were deals on preexisting streets and on new lots opened as a consequence of prolonging older streets.

Despite the expansion of streets in the city, prices did not fall. We were able to calculate prices per square meter for most years, except for the period from 1889 to 1903, and some other years where there was no detailed description of deeds with measurements in meters. We also excluded the deeds that used palms as a

![]()

Table 8. New streets opened in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

Graph 4. New streets opened in Ribeirão Preto (1874-1930). Sources: Primary data: property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

measure, considering it more difficult to standardize, since in some cases two measures appeared together, but the proportion was not correct when compared to others.

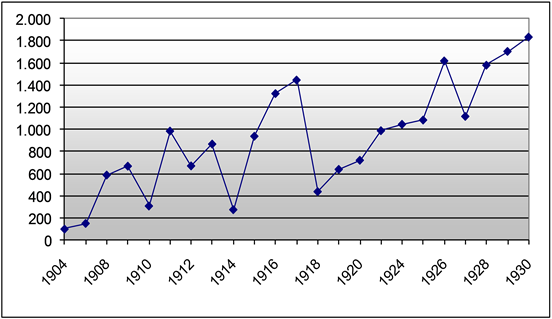

The average price per square meter for a lot in Ribeirão Preto had a strong tendency for increasing during the Old Republic. The dynamism of the coffee crop economy and the consequent need for intensive labor created an almost constant shortage of new dwellings and, as a result, the small urban nucleus expanded into farmland and country houses that surrounded this nucleus. However, in order to make the decision to abdicate gains from the crop, property owners needed additional incentives to transform their lands into new streets and the strong demand together with the willingness on the part of these new residents to pay a higher price ended up being the incentive for selling or for the farmer to divide his land or part of it into lots (Graph 5).

We calculated data for the price per square meter starting in 1904. That year, a lot could be bought in Ribeirão Preto at just 101 réis per square meter, on average. The pace for lot prices despite the cycles of accelerated increases in some moments, had a tendency for constant increases. In 1930, the square meter was already worth 1$834, that is, and appreciation of more than 1700% in real terms.

We additionally sought to separate lots by location using the criterion that frequently appeared in deeds: lots located downtown or on the outskirts. Regardless of the district in which the lot was located, this differentiation was considered very important at the time of describing the property, since it indicated the degree of easy access to most services and commerce in general.

Effectively, this differentiation was significant in determining prices. The level of valorization of the square meter in the downtown sector was much more intense than on the outskirts. In Table 9, we can see that in beginning of the 20th Century, the downtown already had a much more significant value of importance than the outskirts.

Graph 5. Value in réis for the m2 of urban lots (1874-1930). Sources: Primary data: property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

![]()

Table 9. Average value in réis per square meter for lots in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

This was the key to the city’s territorial expansion in relation to the field. As the downtown land values became increasingly more expensive for constructing new urban buildings, interest in areas farther away also increased. The price became the greatest incentive for farmers and small farmers to forgo crop production on their lands in favor of opening new streets, which they opened themselves or bought by third parties who would divide them into lots.

The tendency for price increases in the downtown section of Ribeirão Preto continued throughout the Old Republic. Going from just 170 réis per square meter to 3259 réis in 1930, a 19 fold increase in value indicates a more than proportional increase to land increases in the outskirts, which although always maintaining a slower pace of growth began to have an average value of 279 réis in the 1930s, significantly higher than the values obtained at the turn of the century.

The price increase for outskirt lots was not as expressive as the increases in the downtown four block section. This occurred because the possibilities for expansion at the border between the urban and rural were great, limited only by the prices of farms and country houses that began to be replaced by new districts. This stability ensured that the same year in which there was the highest value per square meter in the downtown section, the average value for the square meter in the outskirts reached 410 réis, that is, just under the square meter quoted in 1912. Therefore, while there was no limit for the valorization of certain areas, in others the limits were very clear and defined by the possibilities and alternative prices between small farms, country houses and farms that surrounded the urban nucleus.

We believe that the urban nucleus expansion process that began in the middle of the field, basically depended on the crop itself and the associated costs of opportunity and other related factors, such as the farmer’s desire to relinquish an area in favor of urban development.

3.6. Urban Homes and Buildings

Dwellings and urban buildings represented 42.04% of total business conducted within the urban ambit of Ribeirão Preto. The property purchase and sale deeds did not detail constructed area for most houses. This made it impossible for us to better understand the appreciation of residential properties.

Of the 1937 dwellings negotiated, the average purchase price was 2.07 contos de réis. Although this is a relatively high price, the average did not reveal the existing peculiarity. We see that the characteristic of this market did not leave a guideline for us to identify a standard of appreciation. In several deeds in which the description of the property did not lead us to believe they were expensive properties, the description of belonging to “John Doe” gave us the impression of being an additional factor for valorization. The status, in these cases, added value to the property. Furthermore, the very characteristic of each property in relation to finishings and details played an implicit role in the price formation of dwellings, as well as the existence of furniture and its quality in a greater or lesser degree. Therefore, the houses form a type of property of greater difficulty for formatting in relation to any logical criteria, as occurred with urban lots and farmland.

In Table 10, we see the distribution in ranges of price negotiations for dwel lings in Ribeirão Preto. Most dwellings were simple houses with little added value, with prices up to 500 thousand réis or no more than one conto de réis. The dwellings with real prices up to one conto de réis had a total share of 50.80% of all trades throughout the period.

Many houses had primary structural conditions but there was still no market for them. In general, these dwellings were negotiated at insignificant prices and in other cases the price considered had more to do with the size of the lot and the vegetable crops or the existence of fruit trees than the house existing on the lot.

![]()

Table 10. Dwellings: ranges of negotiation values in Ribeirão Preto (1889-1930).

Source: Property purchase and sale deeds from the 1st Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto.

In 1907, a small dwelling measuring just 60 palms in the front “covered with pasture” was appraised at 100 thousand réis. Most of these dwellings, besides being covered with pasture, had dirt and not cement floors During the rainy season, this combination caused considerable problems for inhabitants, to the point where these facts were mentioned in the deeds.

The highlight given in the description of the dwelling in the purchase and sale deed served as a reference for us to understand the importance given by traders to some characteristics to the detriment of others, which ended up being secondary. As a result, this demonstrates not only the relative importance of these variables for price formation, but also indicates tendencies and changes in dwelling structures since from the moment most properties have a certain characteristic it becomes unnecessary to highlight it.

In this sense, dirt floors and thatched roofs decreased in importance in the period studied. During the final decade of the 19th Century it was very common to have properties with more precarious finishing. In the beginning of the 20th Century, the incidences of these precarious items diminished and practically disappeared in the 1920s and 1930s. This shows a certain level of minimum requirement on the part of new buyers in relation to aspects such as a standard of comfort, even in simpler dwellings.

4. Final Remarks

The intense development of Ribeirão Preto during the decades surrounding the beginning of the 20th Century, greatly conditioned on the thriving coffee crop economy, demanded significant expansion of the urban real estate market.

In our analysis, aimed at understanding the dynamic of development of Ribeirão Preto in the Old Republic through real estate transactions, we could make some relevant observations.

More than half of the real estate transactions conducted in Ribeirão Preto between 1889 and 1930 (52% of a total of 4607) had lots as an object, which denotes the growing appreciation of urban space created with lots to the detriment of rural production areas. The greater intensity of these transaction occurred in the second and third decades of the 20th Century.

The second large group of negotiations refers to dwellings/urban buildings (42%), indicating the accelerated urbanization process in the period.

In relation to the commercial buildings and dwelling and commercial houses, the fact that Ribeirão Preto establishes itself in this period as an important regional center for shopping and services is seen in the predominance of commercial property transactions (59.2%), followed by properties geared to services (27.7%) and finally, in a much more modest position, industrial properties (13.1%). The modest industrial sector compared to the commercial and service sectors is also seen in the lower average price for these transactions.

The negotiated commercial establishments that stand out are sundries stores, bakeries and pharmacies. Likewise, the prominent participation of hotels in total negotiations of properties in the services sector is also observed. The privileged location of these establishments converges to the area surrounding the railroad station and the municipal market.

It thus becomes clear that Ribeirão Preto’s economic development, which intensified after 1880, created conditions for the exponential growth of real estate transactions, especially in the urban area, with an increase in value and number of real estate transactions.