Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.5 No.14(2014), Article ID:49022,8 pages

DOI:10.4236/jmp.2014.514130

What Does Monogamy in Higher Powers of a Correlation Measure Mean?

Pilukuli Janardhana Geetha1, Sudha1,2*, Alevoor Raghavendra Usha Devi2,3

1Department of Physics, Kuvempu University, Shankaraghatta, Shimoga, India

2Inspire Institute Inc., Alexandria, USA

3Department of Physics, Bangalore University, Bangalore, India

Email: *arss@rediffmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 June 2014; revised 1 July 2014; accepted 25 July 2014

ABSTRACT

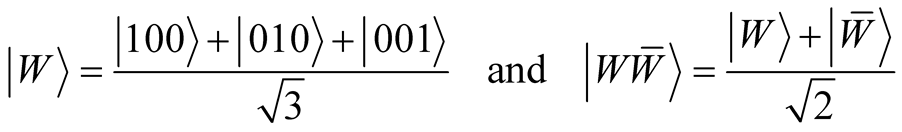

We examine here the proposition that all multiparty quantum states can be made monogamous by considering positive integral powers of any quantum correlation measure. With Rajagopal-Rendell quantum deficit as the measure of quantum correlations for symmetric 3-qubit pure states, we illustrate that monogamy inequality is satisfied for higher powers of quantum deficit. We discuss the drawbacks of this inequality in quantification of correlations in the state. We also prove a monogamy inequality in higher powers of classical mutual information and bring out the fact that such inequality needs not necessarily imply restricted shareability of correlations. We thus disprove the utility of higher powers of any correlation measure in establishing monogamous nature in multiparty quantum states.

Keywords:Mutual Information, Sharing of Classical and Quantum Correlations, Monogamy of Quantum Correlations

1. Introduction

It is well known that classical correlations are infinitely shareable whereas there is a restriction on the shareability of quantum entanglement amongst the several parts of a multipartite quantum state [1] -[4] . The concept of monogamy of entanglement and monogamy of quantum correlations has been studied quite extensively [1] - [23] and it is shown that the measures of quantum correlations such as quantum discord [24] , quantum deficit [25] are not monogamous for some category of pure states [16] [17] . The polygamous nature of quantum correlations other than entanglement has initiated discussions on the properties to be satisfied by a correlation measure to be monogamous [21] and it is shown that a measure of correlations is in general non-monogamous if it does not vanish on the set of all separable states [21] .

While it has been shown that [22] square of the

quantum discord obeys monogamy inequality for

-qubit pure states, an attempt to show that

all multiparty states can be made monogamous by considering higher integral powers

of a non-monogamous quantum correlation measure has been done in Ref. [23] . It is shown that (See Theorem

1 of Ref. [23] ) if

-qubit pure states, an attempt to show that

all multiparty states can be made monogamous by considering higher integral powers

of a non-monogamous quantum correlation measure has been done in Ref. [23] . It is shown that (See Theorem

1 of Ref. [23] ) if

is a non-monogamous correlation measure and is monotonically decreasing under discarding

systems, then

is a non-monogamous correlation measure and is monotonically decreasing under discarding

systems, then ,

,

can be a monogamous correlation measure for

tripartite states [23] . With

quantum work-deficit

can be a monogamous correlation measure for

tripartite states [23] . With

quantum work-deficit

as a correlation measure, it is numerically shown that almost all

as a correlation measure, it is numerically shown that almost all

-qubit pure states become monogamous when

the fifth power of

-qubit pure states become monogamous when

the fifth power of

is considered [23] .

is considered [23] .

In this work, we analyze the implications of the proposition

[23] that higher integral powers of a quantum correlation

measure reveal monogamy in all multiparty quantum states. Towards this end we first

verify the above proposition by adopting quantum deficit

[25] , an operational measure of quantum correlations for our analysis.

Quantum deficit has been shown to be, in general, a non-monogamous measure of correlations

for

- qubit pure states

[17] . In Ref. [17]

, the monogamy properties (with respect to quantum deficit) of symmetric

- qubit pure states

[17] . In Ref. [17]

, the monogamy properties (with respect to quantum deficit) of symmetric

- qubit pure states belonging to

- qubit pure states belonging to

-,

-,

-distinct Majorana spinors classes [26] -[28]

has been examined and it has been shown that all states belonging to the

-distinct Majorana spinors classes [26] -[28]

has been examined and it has been shown that all states belonging to the

-distinct spinors class (including

-distinct spinors class (including

-states) are polygamous. It has also been

shown [17] that the superposition

of

-states) are polygamous. It has also been

shown [17] that the superposition

of , obverse

, obverse

states, belonging to the SLOCC class of 3-distinct Majorana spinors [26] -[28] , are

polygamous with respect to quantum deficit. Here we consider both these classes

of states and illustrate that they can be monogamous with respect to higher powers

of quantum deficit. We examine the possibility of quantification of tripartite correlations

using monogamy relation in higher powers of a quantum correlation measure and illustrate

that such an exercise is unlikely to yield fruitful results.

states, belonging to the SLOCC class of 3-distinct Majorana spinors [26] -[28] , are

polygamous with respect to quantum deficit. Here we consider both these classes

of states and illustrate that they can be monogamous with respect to higher powers

of quantum deficit. We examine the possibility of quantification of tripartite correlations

using monogamy relation in higher powers of a quantum correlation measure and illustrate

that such an exercise is unlikely to yield fruitful results.

In order to analyze the relevance of monogamy with respect to higher integral powers of a quantum correlation measure, we bring forth a monogamy-kind-of-an-inequality in higher powers of classical mutual information [29] . The possibility of a monogamy relation in higher powers of a classical correlation measure even in the arena of classical probability theory raises questions regarding the meaning attributed to such an inequality. We discuss this aspect and bring out the fact that monogamy in higher powers of a quantum correlation measure needs not necessarily imply limited shareability of correlations.

2. Monogamy of 3-Qubit Pure States with Respect to Higher Powers of Quantum Deficit

Quantum deficit, a useful measure of quantum correlations was proposed by Rajagopal

and Rendell [25] while enquiring into the circumstances

in which entropic methods can distinguish the quantum separability and classical

correlations of a composite state. It is defined as the relative entropy [29] of the state

with its classically decohered counterpart

with its classically decohered counterpart . That is,

. That is,

(1)

(1)

is the quantum deficit of the state

and it determines the quantum excess of correlations in

and it determines the quantum excess of correlations in

with reference to its classically decohered counterpart

with reference to its classically decohered counterpart . As

. As

is diagonal in the eigenbasis

is diagonal in the eigenbasis ,

,

of the subsystems

of the subsystems ,

,

(common to both

(common to both ,

, ) one can readily

evaluate

) one can readily

evaluate

as [17]

as [17]

(2)

(2)

where

are the eigenvalues of the state

are the eigenvalues of the state

and

and

denote the diagonal elements of

denote the diagonal elements of . Through an explicit evaluation

of the quantum deficit

. Through an explicit evaluation

of the quantum deficit , the polygamous nature

(with respect to quantum deficit

, the polygamous nature

(with respect to quantum deficit ) of two SLOCC inequivalent

classes of symmetric

) of two SLOCC inequivalent

classes of symmetric

-qubit pure states has been illustrated in Ref.

[17]

. In particular, it is shown that [17] the

monogamy relation

-qubit pure states has been illustrated in Ref.

[17]

. In particular, it is shown that [17] the

monogamy relation

(3)

(3)

is not satisfied for symmetric

-qubit states with

-qubit states with

-distinct Majorana spinors

[26] -[28] . Amongst the

-distinct Majorana spinors

[26] -[28] . Amongst the

-qubit GHZ and superposition of

-qubit GHZ and superposition of , obverse

, obverse

states, the monogamy inequality (3) is satisfied by the GHZ states while the superposition

of

states, the monogamy inequality (3) is satisfied by the GHZ states while the superposition

of

and obverse

and obverse

states does not obey it

[17] inspite of both the

states belonging to the SLOCC family of

states does not obey it

[17] inspite of both the

states belonging to the SLOCC family of

-distinct spinors [28]

.

-distinct spinors [28]

.

In the following we illustrate that symmetric

-qubit pure states obey monogamy relation in higher

powers of quantum deficit

-qubit pure states obey monogamy relation in higher

powers of quantum deficit . The states of interest

are given by,

. The states of interest

are given by,

(4)

(4)

where

is the obverse

is the obverse

state.

state.

The reduced density matrices of the

-qubit

-qubit

state are given by

state are given by

(5)

(5)

With ,

,

being the eigenvectors of

being the eigenvectors of , the decohered counterpart

, the decohered counterpart

of

of

is obtained as

[17]

is obtained as

[17]

(6)

(6)

As ,

,

are the non-zero eigenvalues of

are the non-zero eigenvalues of , we obtain the quantum

deficit

, we obtain the quantum

deficit

to be,

to be,

(7)

(7)

An evaluation of the eigenvectors ,

,

of the bipartite subsystems

of the bipartite subsystems

of the state

of the state

allows us to find out the decohered counterpart

allows us to find out the decohered counterpart

of the state

of the state

and we have

and we have

(8)

(8)

The quantum deficit

of the

of the

state is thus obtained as,

state is thus obtained as,

It is easy to see that

(9)

(9)

and the monogamy inequality (3) is not obeyed [17] .

For the state , the reduced density matrices

are

, the reduced density matrices

are

(10)

(10)

and their common non-zero eigenvalues are ,

, . The decohered density

matrices

. The decohered density

matrices ,

,

are respectively given by

[17]

are respectively given by

[17]

(11)

(11)

The quantum deficit

and

and

are therefore obtained as

are therefore obtained as

(12)

(12)

Here too we have

(13)

(13)

and the monogamy inequality (3) is not obeyed [17] .

Having illustrated the polygamous nature of the states ,

,

with respect to quantum deficit, we wish to see

whether higher powers of quantum deficit indicate monogamy in these and if so for

what powers. In Table 1, we have tabulated

with respect to quantum deficit, we wish to see

whether higher powers of quantum deficit indicate monogamy in these and if so for

what powers. In Table 1, we have tabulated ,

,

and the value of

and the value of ,

,

for both

for both

and

and .

.

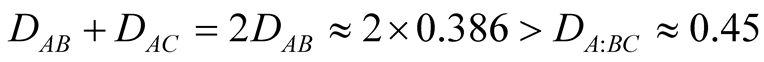

It can be readily seen from the table (Table 1)

that though the

-qubit states

-qubit states

and

and

are polygamous with respect to quantum deficit, its third power satisfies monogamy

inequality for

are polygamous with respect to quantum deficit, its third power satisfies monogamy

inequality for

whereas fifth power of quantum deficit is required for making the state

whereas fifth power of quantum deficit is required for making the state

monogamous.

monogamous.

We have also examined the monogamy with respect to ,

,

for an arbitrary symmetric 3qubit pure state belonging

to the family of

for an arbitrary symmetric 3qubit pure state belonging

to the family of

-distinct spinors

[17]

. The state is given by

[17]

-distinct spinors

[17]

. The state is given by

[17]

(14)

(14)

with

and for

and for , we get the

, we get the

state. An explicit evaluation of

state. An explicit evaluation of ,

,

, as a function of

, as a function of , has been done in

Ref. [17]

and the state is seen to be polygamous for all values

, has been done in

Ref. [17]

and the state is seen to be polygamous for all values . But in higher powers

of

. But in higher powers

of

, monogamy inequality

is satisfied and as the power

, monogamy inequality

is satisfied and as the power

increases more states become monogamous. Figure 1 illustrates this feature. Notice

that the state is not monogamous in terms of quantum deficit as can be seen through

the negative values of

increases more states become monogamous. Figure 1 illustrates this feature. Notice

that the state is not monogamous in terms of quantum deficit as can be seen through

the negative values of , throughout the whole

range, when

, throughout the whole

range, when . When

. When , more states become

monogamous as can be seen through the non-negative values of

, more states become

monogamous as can be seen through the non-negative values of

for

for

and

and .

.

At this juncture, it would be of interest to know whether quantification of non-classical correlations in a tripartite state is possible through the monogamy inequality in higher powers of the correlation measure. Notice that monogamy inequalities in squared concurrence [1] , squared negativity [5] have been useful in quantifying the tripartite correlation through concurrence tangle [1] and negativity tangle [5] . A systematic attempt to quan.

Figure 1.

The plot of

versus

versus

for 3-qubit pure states with 2-distinct spinors.

for 3-qubit pure states with 2-distinct spinors.

tify the correlations in

-qubit pure states using square of quantum discord

as the measure of quantum correlations has been done in Ref.

[22] . We observe here that in order to quantify the tripartite correlations

using monogamy inequality in

-qubit pure states using square of quantum discord

as the measure of quantum correlations has been done in Ref.

[22] . We observe here that in order to quantify the tripartite correlations

using monogamy inequality in , one has to consider the

non-negative quantity

, one has to consider the

non-negative quantity , where

, where

is the minimum degree at which the state becomes monogamous. But there immediately

arise questions regarding whether the minimum degree

is the minimum degree at which the state becomes monogamous. But there immediately

arise questions regarding whether the minimum degree

of

of

has any bearing on the amount of non-classical tripartite correlations in the state.

In fact, every correlation measure requires a different integral power

has any bearing on the amount of non-classical tripartite correlations in the state.

In fact, every correlation measure requires a different integral power

to reveal monogamous nature in a

to reveal monogamous nature in a

-qubit state [23]

. Whereas fifth power of quantum discord is sufficient to make almost all

-qubit state [23]

. Whereas fifth power of quantum discord is sufficient to make almost all

-qubit pure states monogamous

[23] , we have seen here that one requires still higher powers in

quantum deficit

-qubit pure states monogamous

[23] , we have seen here that one requires still higher powers in

quantum deficit

(See Figure 1) for some pure symmetric

(See Figure 1) for some pure symmetric

-qubit states. As such there does not appear to

be any relation between the non-classical correlations in the state and the minimum

degree

-qubit states. As such there does not appear to

be any relation between the non-classical correlations in the state and the minimum

degree

of a correlation measure. For instance, we have (See Table

1)

of a correlation measure. For instance, we have (See Table

1)

Also, as

for

for

-qubit GHZ state

[17]

, we have

-qubit GHZ state

[17]

, we have

at

at

for GHZ state. It is not apparent whether states having higher correlations possess

larger

for GHZ state. It is not apparent whether states having higher correlations possess

larger

with smaller value of

with smaller value of

or vice versa. Whichever be the case, the way in which

or vice versa. Whichever be the case, the way in which

can be accommodated in finding the tripartite correlations is not evident even in

these simplest examples. Also, the monogamy relation in higher powers of a correlation

measure

can be accommodated in finding the tripartite correlations is not evident even in

these simplest examples. Also, the monogamy relation in higher powers of a correlation

measure

will not have the physical meaning of restricted shareability of correlations if

will not have the physical meaning of restricted shareability of correlations if

is not established as a proper correlation measure satisfying essential properties

such as local unitary invariance. The tripartite correlation measure

is not established as a proper correlation measure satisfying essential properties

such as local unitary invariance. The tripartite correlation measure

should also be established as a valid correlation measure1 for each

should also be established as a valid correlation measure1 for each . Without addressing these issues, a mere quantification

of tripartite correlations through

. Without addressing these issues, a mere quantification

of tripartite correlations through

may not yield justifiable results.

may not yield justifiable results.

3. Monogamy-Kind of Relation in Higher Powers of Mutual Information

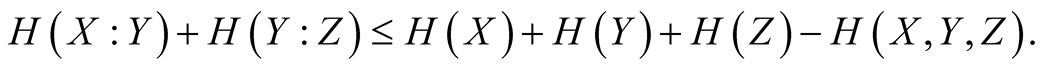

We now go about exploring the meaning associated with monogamy in positive integral powers of a correlation measure. Towards this end, we prove a monogamy-kind-of-a relation in higher powers of classical mutual information and investigate its consequences.

From the strong subadditivity property of Shannon entropy [29] , we have,

(15)

(15)

Casting Equation (15) in terms of the mutual information [29]

we obtain

and this implies

(16)

(16)

In view of the fact that

where

where

denotes the mutual information between the random variables

denotes the mutual information between the random variables ,

,

, we make use of the relation

, we make use of the relation

in Equation (16) to obtain

in Equation (16) to obtain

As ,

,

we obtain the relation

we obtain the relation

(17)

(17)

obeyed by the trivariate joint probability distribution

indexed by the random variable

indexed by the random variable

. Notice that the relation

. Notice that the relation

(18)

(18)

represents a monogamy relation between the random variables ,

,

and

and . But this inequality

is not true due to the existence of the non-negative term

. But this inequality

is not true due to the existence of the non-negative term

on the right hand side of Equation (17). That is we have,

on the right hand side of Equation (17). That is we have,

(19)

(19)

According to Theorem 1 of Ref. [23] , a non-monogamous measure of correlations satisfies monogamy inequality in higher integral powers when the measure is decreasing under removal of a subsystem. Thus, in order to prove the monogamy relation in higher powers of mutual information, we need to establish that

We show in the following that mutual information indeed is non-increasing under removal of a random variable.

On making use of the relations

we have,

(20)

(20)

As ,

,

denote the respective conditional entropies,

Equation (20) simplifies to

denote the respective conditional entropies,

Equation (20) simplifies to

Using the fact that conditioning reduces entropy, i.e.,

, we readily have

, we readily have

(21)

(21)

One can similarly show that

(22)

(22)

We are now in a position to prove the monogamy relation

(23)

(23)

based on the proof of Theorem 1 of Ref. [23]

. Here

is the lowest integer for which the above equality is satisfied.

is the lowest integer for which the above equality is satisfied.

Denoting

(24)

(24)

we have

(See Equation (19)),

(See Equation (19)),

,

, (See Equaitons (21), (22)) and hence

(See Equaitons (21), (22)) and hence ,

,

which follow from the non-negativity of mutual

information and from Equaitons (19), (21), (22). This implies

which follow from the non-negativity of mutual

information and from Equaitons (19), (21), (22). This implies ,

,

and hence

and hence

there exist positive integers

there exist positive integers ,

,

such that,

such that,

(25)

(25)

With a choice of

we get

we get

and

and ,

,

positive integers

positive integers , where

, where

we readily obtain the inequality

we readily obtain the inequality

(26)

(26)

which is essentially the monogamy relation Equation (23).

Having established the monogamy relation in higher powers of classical mutual information (See Equation (23)), we now examine its implications. In fact, we are interested in knowing whether the monogamy relation in higher powers of a correlation measure (classical/quantum) reflects restricted shareability of correlations. Towards this end we raise the following questions.

a) Does Equation (23) imply that the distribution of bipartite correlations between ,

,

and

and ,

,

are restrictively shared among the random

variables

are restrictively shared among the random

variables ,

,

,

,

in the trivariate probability distribution

in the trivariate probability distribution ?

?

b) If a classical correlation measure satisfies monogamy inequality in its higher powers, does it mean limited shareability of classical correlations in a quantum state?

c) What does the monogamy relation satisfied by higher power of a non-monogamous measure of quantum correlations mean?

An affirmative answer to (a) and (b) negates the unrestricted shareability of classical correlations. But it is well known that classical correlations in a multiparty quantum state can be distributed at will amongst its parties. This implies we need to negate both the statements (a) and (b). Now it is not difficult to see that negation of (a) and (b) immediately provides an answer to (c).

Existence of a monogamy relation in higher powers of any correlation measure (classical or quantum) does not necessarily mean restricted shareability of correlations in a multiparty state.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have illustrated that monogamy relation satisfied in higher powers of a non-monogamous correlation measure is not useful either to quantify the correlations or to signify that all mutiparty states have restricted shareability of correlations. We hope that this work is helpful in clarifying whether or not higher powers of quantum correlation measure are to be taken up for examining the monogamous nature of quantum states.

Acknowledgements

P. J. Geetha acknowledges the support of Department of Science and Technology (DST), Govt. of India through the award of INSPIRE fellowship.

References

- Coffman. V., Kundu. J. and Wootters, W.K. (2000) Physical Review A, 61, Article ID: 052306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.61.052306

- Osborne, T.J. and Verstraete, F. (2006) Physical Review Letters, 96, Article ID: 220503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.220503

- Koashi, M. and Winter, A. (2004) Physical Review A, 69, Article ID: 022309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.69.022309

- Yang, D. (2006) Physics Letters A, 360, 249-250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2006.08.027

- Ou, Y.-C. and Fan, H. (2007) Physical Review A, 75, Article ID: 062308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.75.062308

- Yu, C.-S. and Song, H.-S. (2008) Physical Review A, 77, Article ID: 032329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.77.032329

- Kim. J.S., Das, A. and Sanders, B.C. (2009) Physical Review A, 79, Article ID: 012329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.79.012329

- Lee, S. and Park, J. (2009) Physical Review A, 79, Article ID: 054309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.79.054309

- de Oliveira, T.R. (2009) Physical Review A, 80, Article ID: 022331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.80.022331

- Cornelio, M.F. and de Oliveira, M.C. (2010) Physical Review A, 81, Article ID: 032332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.81.032332

- Kim, J.S. and Sanders, B.C. (2011) Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 44, Article ID: 295303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/44/29/295303

- Zhao, M.J., Fei, S.M. and Wang, Z.X. (2010) International Journal of Quantum Information, 8, 905. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0219749910006216

- Seevinck, M.P. (2010) Quantum Information Processing, 9, 273-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11128-009-0161-6

- Giorgi, G.L. (2011) Physical Review A, 84, Article ID: 054301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.84.054301

- Fanchini, F.F., de Oliveira, M.C., Castelano, L.K. and Cornelio, M.F. (2013) Physical Review A, 87, Article ID: 032317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.87.032317

- Prabhu, R., Pati, A.K., Sen De, A. and Sen, U. (2012) Physical Review A, 85, Article ID: 040102(R). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.85.040102

- Sudha, Usha Devi, A.R. and Rajagopal, A.K. (2012) Physical Review A, 85, Article ID: 012103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.85.012103

- Ren, X.J. and Fan, H. (2013) Quantum Information & Computation, 13, 469-478. http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.5163

- Liu, S.Y., Zhang, Y.R., Zhao, L.M., Yang, W.L. and Fan, H. (2013) Annals of Physics, 348, 256. arXiv:1307.4848v2. http://arxiv.org/abs/1307.4848v2

- Liu, S.Y., Li, B., Yang, W.L. and Fan, H. (2013) Physical Review A, 87, Article ID: 062120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.87.062120

- Streltsov, A., Adesso, G., Piani, M. and Bruss, D. (2012) Physical Review Letters, 109, Article ID: 050503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.050503

- Bai, Y.K., Zhang, N., Ye, M.Y. and Wang, Z.D. (2013) Physical Review A, 88, Article ID: 012123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.88.012123

- Salini, K., Prabhu, R., Sen De, A. and Sen, U. (2012) Annals of Physics, 348, 297. arXiv: 1206.4029. http://arxiv.org/abs/1206.4029

- Ollivier, H. and Zurek, W.H. (2002) Physical Review Letters, 88, Article ID: 017901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.017901

- Rajagopal, A.K. and Rendell, R.W. (2002) Physical Review A, 66, Article ID: 022104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.66.022104

- Majorana, E. (1932) Il Nuovo Cimento, 9, 43-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02960953

- Bastin, T., Krins, S., Mathonet, P., Godefroid, M., Lamata, L. and Solano, E. (2009) Physical Review Letters, 103, Article ID: 070503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.070503

- Usha Devi, A.R., Sudha and Rajagopal, A.K. (2012) Quantum Information Processing, 11, 685.

- Nielsen, M.A. and Chuang, I.L. (2002) Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.

1For square of quantum discord,

is shown to satisfy all properties of a correlation

measure in Ref. .

is shown to satisfy all properties of a correlation

measure in Ref. .